PBOC Swap Lines and the IMF in the Global Financial Architecture: Competition or Cooperation?

By Julian Watrous and Stephen Paduano

The last two decades have seen a fundamental shift in global sovereign lending patterns. By the late 2010s, China emerged as the world’s largest official bilateral creditor. China’s record of infrastructure financing, primarily through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), is now well-known. More recent, and less theorized, is China’s rise as a sovereign lender of last resort.

Beginning around 2009, China began providing large bilateral foreign exchange swap lines, which some borrowing countries have used for macroeconomic crisis support. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has now provided more than $38 billion to 13 central banks (with overall swap line access totaling $448 billion at end-2021 to 40 central banks), raising interesting and peculiar questions about whether China is emerging as a — perhaps the — new lender of last resort. Concurrently, the Paris Club group of developed country sovereign creditors, which historically played a large role in bilateral lending, now makes up only a fraction of overall sovereign debt.

The rise of Chinese bilateral emergency lending is a significant disruption to the status quo since 1944, in which the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has acted as the central global lender of last resort. The Global Financial Safety Net (GFSN), historically dominated by Western countries, functioned as a largely coordinated process between the IMF, other multilateral lenders and developed country bilateral lenders. With the rise of Chinese balance-of-payments lending, however, some countries facing economic crises may now have an outside emergency financing option, which they may be tempted to tap instead of an IMF program. Whereas the IMF imposes burdensome policy conditions on its borrowers, China typically make loans with few or no policy conditions. This has led to claims that new balance-of-payments lenders represent a genuinely independent alternative to IMF financing.

Our new working paper published by the Boston University Global Development Policy Center takes a close look at the role of China’s swap line network within the GFSN. By examining each case of PBOC swap line usage, we investigate how countries use PBOC swap lines during financial distress, and consider whether these arrangements genuinely constitute an alternative to the IMF for emergency financing. Finding that they generally do not displace IMF loans, we ask how they interact with existing IMF programs, and how they have transformed the GFSN—all while considering how they might develop in the future.

How are PBOC swap lines being used?

While we cannot definitively identify the full scope of renminbi (RMB) swap line usage—i.e., if there are short-term trade and investment use cases that net out before a quarterly or annual reporting period—it appears that one central, if not predominant, use case has been emergency balance-of-payments support.

As of the end of 2021, 13 countries had drawn $38 billion in balance-of-payments support. Since 2009, PBOC swap line draws (excluding rollovers) have amounted to 12 percent of overall IMF lending (or 55 percent including rollovers) in terms of disbursements over the same period, though overall access nearly rivals IMF resources.

These 13 recipient central banks have drawn on their PBOC swap lines as a new source of external financing to help close financing gaps when new external bond issuance was prohibitively expensive. Central banks have used the RMB proceeds for two main purposes: to shore up gross foreign reserves and to make external debt payments—to China, multilateral creditors or private sector creditors—to avoid default.

Shoring up gross foreign reserves has been the most common use case. In some cases, PBOC swap draws have represented more than half of a given country’s gross reserves (as in Argentina and Mongolia). In the second type of use case—making external debt payments—swap lines have mostly been used in-and-around external default episodes. For example, Pakistan drew on its swap to pay down maturing debt to Saudi Arabia in 2021, and Argentina drew on its swap to make payments to external bondholders and repay IMF debt in 2023.

Do PBOC swap lines substitute for IMF financing?

Overall, countries have not used PBOC swap lines as a substitute for IMF financing. While a short list of countries have drawn on their PBOC swap lines without also turning to the IMF, a much longer list of countries either 1) had access to PBOC swap lines yet only drew on IMF financing, 2) simultaneously borrowed from the IMF and from the PBOC as supplementary financing, or 3) initially sought to avoid IMF financing through bilateral substitution, but eventually turned to the IMF.

These cases hint that PBOC swap lines have mostly not offered a fully viable alternative to IMF programs. The first set of cases indicates that for some countries, IMF financing is preferable to PBOC swap lines, despite the conditionalities imposed. In the second set, borrowers may have found PBOC swaps to be useful additions to IMF programs, but not full substitutes. In the third, borrowers may have initially resisted IMF programs and their policy demands, but later found themselves in need of more financing.

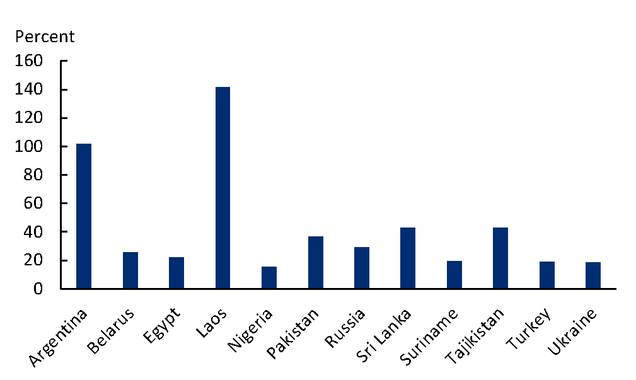

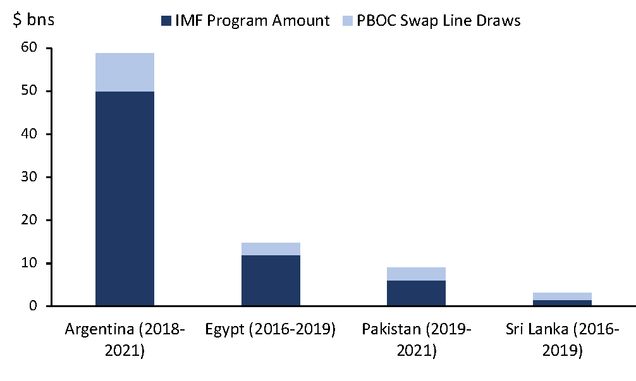

Through a detailed comparison of financing instruments, we find that PBOC swap lines do not represent a full substitute for the IMF for countries facing balance-of-payment crises. Specifically, we highlight a few key features that limit their use as an IMF-alternative: duration, cost, limited financing amounts and RMB-denomination. While the relative lack of conditionality may appeal to borrowers, PBOC swap lines naturally have a much shorter duration compared to IMF loans. Pricing comparisons are difficult to make, but mostly PBOC swaps with emerging market countries have also been more expensive (ranging between 200 and 400 bps above SHIBOR) than IMF financing, which may further compound debt sustainability issues (though we note data limitations and that PBOC swaps may have become relatively cheaper recently as IMF loans have become more expensive). Beyond pricing points, the amount of financing available through PBOC swap lines is in some cases insufficient (Figures 1 and 2). Additionally, they are denominated in RMB, which is less useful than more easily convertible Special Drawing Rights (SDRs).

Figure 1: PBOC Swap Line Access as % of Cumulative IMF Access

Figure 2: Selected Financing Amount Comparisons

However, several countries –five in total—have indeed used their PBOC swap lines as balance-of-payments support during macroeconomic crises without IMF support. These include Nigeria (though it tapped an IMF rapid financing instrument but not an upper-credit tranche program), Russia, Turkey, Belarus and Laos. The case of Turkey may be the most interesting: it drew down the maximum amount ($5.5 billion) under its PBOC swap line while rejecting the possibility of an IMF program. This allowed Turkey to maintain its unorthodox monetary policy of low interest rates amid high inflation and depreciation—a strategy the IMF would surely have urged against under any program. In that case, PBOC swap lines seem to have allowed for greater policy autonomy. The case of Russia—which drew on its swap line after the imposition of international sanctions—is idiosyncratic, given IMF financing would have been impossible under the geopolitical context.

Have PBOC swap lines been a useful addition to the GFSN?

While they have not served as a full substitute for IMF financing, PBOC swap lines have added to the GFSN in two main overlapping contexts: 1) as bridge loans to secure IMF programs and 2) as supplementary financing to bolster existing IMF programs. In the first case, PBOC swap lines simply enable IMF programs by meeting short-term liquidity during program negotiations, helping countries meet IMF programs’ prior conditions or clear IMF arrears. In the second case, PBOC swap lines bolster IMF programs by acting as “supplementary financing,” helping to close external financing gaps.

The growing complexity of the GFSN, which includes PBOC swap lines, presents both opportunities and challenges for developing countries. On one hand, alternative sources of balance-of-payments support can offer policy flexibility and fulfill a short-term liquidity role, proving especially beneficial during external shocks when domestic fiscal adjustments may not be necessary – or even desired. On the other hand, when domestic adjustments or debt restructuring are essential, relying on the availability of these alternative liquidity options, like swap lines, might inadvertently extend the duration of the crisis. The delay in resolving crises is partially the result of the lack of a strong sovereign debt restructuring architecture: if countries cannot reliably restructure their debt through mechanisms like the Group of 20 (G20) Common Framework, the impulse to tap potentially-unsustainable short-term financing is naturally greater. Still, while PBOC swap lines are by no means the cause of the world’s faulty restructuring architecture, their existence compounds what we perceive to be a problem: that countries that ought to restructure find ways to carry their unsustainable debt burdens forward.

Policy implications

The rise of PBOC swap lines in dispensing sovereign rescue loans has thus far not undermined the IMF’s central role in economic crisis management. For the most part, PBOC swap lines do not substitute for IMF financing. They largely address gaps in the existing GFSN rather than directly challenging it: swap lines serve a helpful role by enabling and bolstering IMF programs. In this way, short-term bilateral stabilization loans provided through PBOC swap lines play a role that the United States used to play but has largely abandoned since the 1990s.

We suggest that beyond their immediate role for borrowing countries, PBOC swap lines could create welfare-enhancing geoeconomic competition. Rather than simply discouraging their use, a constructive response from Western countries might involve “competing” by developing similar tools. This could include expanding the Federal Reserve’s swap lines, FIMA Repo Facility and/or the European Central Bank’s EUREP to serve more countries, or reviving the Treasury-based US Exchange Stabilization Fund. Such competition could benefit the GFSN by ensuring more countries have access to emergency liquidity during crises. At the multilateral level, it might even encourage the IMF to reform its lending practices by reducing interest rates or reconsidering its surcharges policy. PBOC swap lines are, to a large degree, a reflection of the patchiness of the existing GFSN. Absent bilateral and multilateral policy reforms by China’s strategic competitors, attempts to discourage the use of PBOC swap lines will fall short.

Read the Working Paper*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global China Initiative Newsletter.