Testimony before the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission – Consumer Products from China: Safety, Regulations and Supply Chains

Editor’s Note: The following testimony was delivered by Dr. Rebecca Ray to the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission hearing on Consumer Products from China: Safety, Regulations and Supply Chains on March 1, 2024.

Good afternoon. Thank you for the opportunity to testify before the Commission today. I would like to start by congratulating the Commissioners on an important and timely choice of topic. Global supply chains are shifting and now is an important moment to consider the readiness of our policy frameworks for these changes.

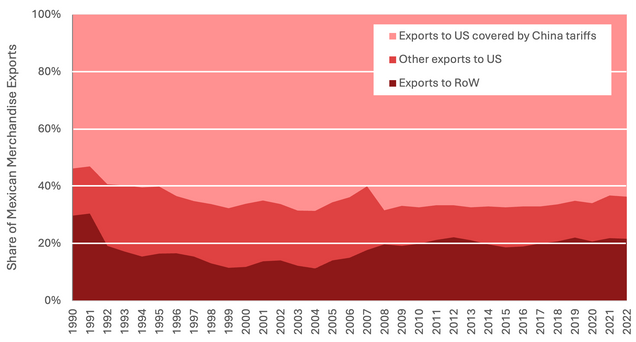

Recent shifts in global value chains are partly in reaction to the United States’ Section 301 tariffs on certain Chinese goods, enacted in 2018. The sectors covered by these tariffs make up most of Mexico-US merchandise exports, as Figure 1 shows. Thus, it is reasonable to expect that Mexico may see an increase in investment and exports to the US in these sectors as firms seek to relocate to reduce costs.

Figure 1: Item Categories Covered by China Tariffs as a Share of Mexico-US Exports

Note: RoW: Rest of world.

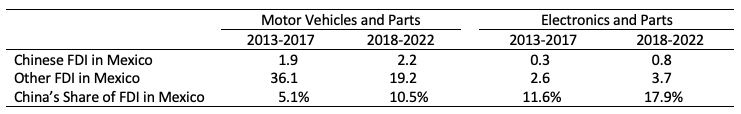

Preliminary investment data reinforces this possibility. As Table 1 shows, Chinese investment in Mexico’s vehicle and electronics sectors have increased significantly since the tariffs took effect, both in absolute terms and as a share of Mexico’s total investment. In fact, new data for 2023 shows that this growth has continued to accelerate, particularly in the vehicle sector. In 2023 alone, new Chinese investment in the Mexican motor vehicles and parts sector increased to over $4 billion, or approximately as much as the entire previous decade of Chinese investment in this sector in Mexico.

Table 1: Chinese Participation in Mexican FDI, Selected Sectors

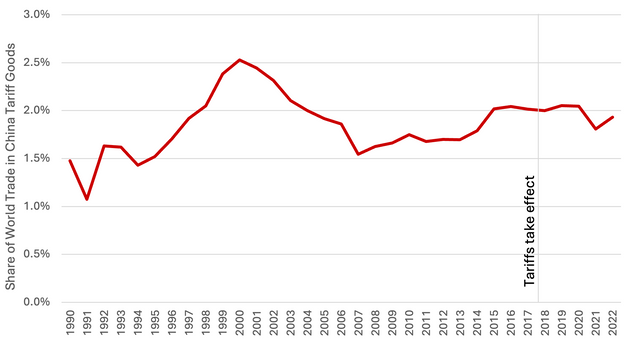

These new Chinese investments have not yet resulted in increased Mexico-US exports, as Figure 2 shows, although they may do so soon. While some of these investments involve Chinese auto-makers manufacturing brands of cars that are not sold in the United States, such as BYD and MG, others will surely result in greater Mexico-US exports in the coming few years.

Figure 2: Mexico-US Exports as a Share of World Trade in Goods Covered by China Tariffs

At this critical juncture, the US and Mexico should review the existing trade and investment policy framework of the United States-Canada-Mexico Agreement (USMCA) on trade and ensure that it is able to manage any economic, social or environmental risks that may come from increase Chinese investment in Mexico.

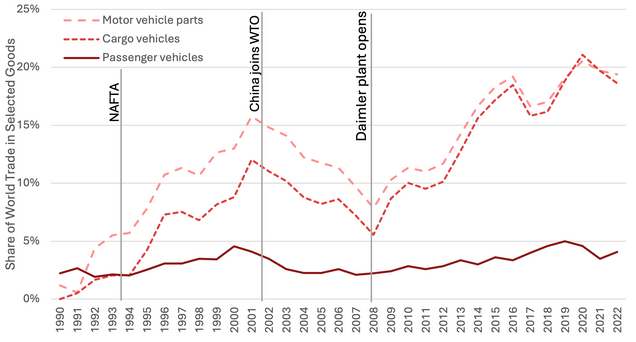

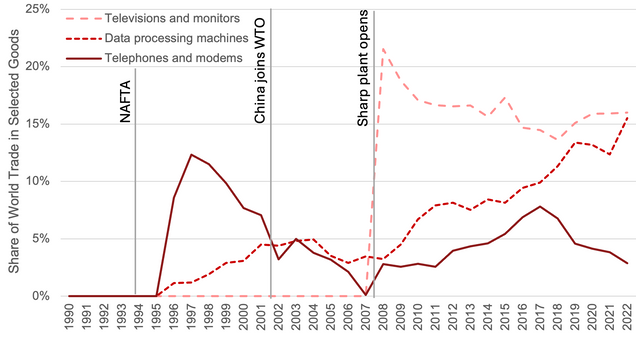

Mexico and the United States do not find themselves in a new situation here, but rather returning to the period of 1994-2001, after the start of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) but before China had joined the World Trade Organization (WTO). During that time, Mexican exports to the US soared in a few sectors, including those targeted by the US’s new tariffs: especially cargo trucks, vehicle parts, and some consumer electronics, as Figures 3 and 4 show. Once China joined the WTO at the end of 2001, production shifted toward China for many of Mexico’s export sectors. Thus, the shifts the North American region is currently experiencing may be reminiscent of the late 1990s.

Figure 3: Mexico-US Motor Vehicle Exports as a Share of World Trade

Figure 4: Mexico-US Electronics Exports as a Share of World Trade

Note: HS tariff lines include targeted goods under the 8471 heading for data processing machines, the 8528 heading for televisions and monitors and the 8517 heading for telephones and modems.

Based on the Chinese investment trends in Table 1, and particularly last year’s rush of motor vehicle investment, now is an important time to review the provisions of USMCA, which replaced NAFTA in 2000, as it relates to vehicle trade, in particular. In this regard, USMCA already represents significant strengthening of protections along economic, social and environmental fronts compared to NAFTA.

First, USMCA brought an increase in the regional value content (or RVC) requirements. While NAFTA required between 60 and 63 percent RVC for goods in the vehicle sector, USMCA has raised this to between 65 and 75 percent, dampening evasion relative to trade with other partners. Furthermore, USMCA introduced labor value content (LVC) rules: now at least 40 percent of a vehicle’s production value must be made by workers earning at least $16 per hour. Finally, USMCA brought both labor and environmental provisions into the main USMCA agreement rather than side agreements, facilitating and strengthening enforcement.

In these ways, Mexican and US economies, workers and environments are better protected than they were in the late 1990s. However, opportunities do remain for continued strengthening of protections. For example, treaty dispute settlement is a cumbersome process. Primary labor and environmental enforcement rests within each country’s domestic institutions. In this regard, it is important to note that the last decade of academic research, including by the Boston University Global Development Policy Center and partners throughout Latin America, shows that Chinese investors tend to not pressure host governments to lower or evade those standards. They also tend not to encourage governments to raise those standards, either. However, our research has found that host countries have considerable policy space to strengthen standards without fear of losing Chinese investment. Therefore, in any investment boom, it is important to ensure that institutional capacity is sufficient for the challenge of overseeing investor performance.

The US has several opportunities to ensure new Chinese investment and new Mexico-US exports meet Mexican and US policy goals. First, the US can lead by example by building on the successes of the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGI). The PGI coordinates Group of 7 (G7) countries’ lending and investment advantages to bring high-quality investment in critical sectors to developing countries. Well designed and operated investment through the PGI can raise expectations for performance of other international investors.

Secondly, the US can work with multilateral bodies such as the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) to encourage Chinese investors to work through established regional mechanisms, rather than independently, so as to ensure investments adhere to the highest international standards. The IDB’s joint investment platform with China channeled Chinese capital through a regional body with some of the highest social and environmental standards among development financial institutions globally. It was established in 2012 and expected to last about a decade. Now, 12 years later, this kind of oversight is at least as necessary as it was then, if not more so. President Biden and Treasury Secretary Yellen have stated their support for a capital increase for IDB Invest, the IDB’s equity investment arm. The US’s formal support for this capital increase at the IDB’s Annual Meeting in March 2024 can bring high-quality direct investment and help coordination with non-regional member countries like China.

Finally, the US can continue to strengthen direct cooperation between the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Department of Labor (DOL) with their Mexican counterparts. EPA and DOL have a long and successful history of direct international collaboration. These avenues of cooperation and communication will be crucial for accountability as the region faces changing investment and trade patterns.

In short, now is an opportune time for the US and Mexico to review policy frameworks are attuned to the opportunities and challenges of international investments and financial flows, and for the US in particular to build on the successes of the PGI, work with multilateral bodies like the IDB and strengthen direct cooperation between the US and our Mexican counterparts.

Thank you again for this opportunity to testify. I look forward to our discussion.

Read the Full Testimony