Capitalizing on China’s Demand for LAC’s Transition Materials: A New Research Agenda Takes Shape

Global annual new energy generation capacity will need to be 90 percent renewable between 2022-2030 to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Significant increases in the production of transition materials, especially lithium and copper, are necessary to support this growth and will likely lead to a commodity boom for such materials.

The relationship between Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), as the majority supplier for key transition materials, and China, as the majority stakeholder in solar and wind energy manufacturing and assembly, is a central artery in the global supply chain for renewable energy and is likely to shape the ability of the global community to reach its energy goals.

What are the structural factors and market conditions that are poised to shape a likely commodity boom to support future energy transitions? What are governance lessons for development and risk mitigation from past commodity booms? And what is the role of outside stakeholders, such as multilateral and Chinese development finance institutions, in supporting institutions and building integrated supply chains?

The Working Group on Development and Environment in the Americas, convened by the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, the Universidad del Pacífico’s Centro de Estudios sobre China y Asia-Pacífico and Peking University’s Institute for New Structural Economics, in August 2022, met to develop a policy-oriented research agenda to address the challenges of governing the impending commodity boom for transition materials. This workshop included input from 24 members of the Working Group, representing universities, governments, inter-governmental organizations and non-governmental organizations.

A new report by the Working Group reviews existing knowledge to identify knowledge gaps and proposes a research agenda to fill them. In all, the Working Group strongly recommends the pursuit of research that bridges disciplinary, geographical and institutional boundaries in order to leverage multiple sources of expertise.

Substantively, the report identifies three major knowledge gaps, stemming from changing local, national and global conditions confronting the coming commodity boom that differ from the contexts of previous booms. First, changes in the structure of the global economy and supply chains for transition materials present challenges for LAC countries with varying technical, financial and policy capacities. Second, these new supply chains and extractive patterns necessitate new governance frameworks for LAC countries to achieve development goals while mitigating social and environmental risks. Third, LAC states must coordinate between a plethora of external stakeholders, including the Chinese government, Chinese commercial actors, Western-led and Southern-led multilateral development banks (MDBs), national development banks (NDBs) and Western private investors, each with their own expertise and interests.

Confronting a New Global Economy, Supply Chains and Geopolitical Environment

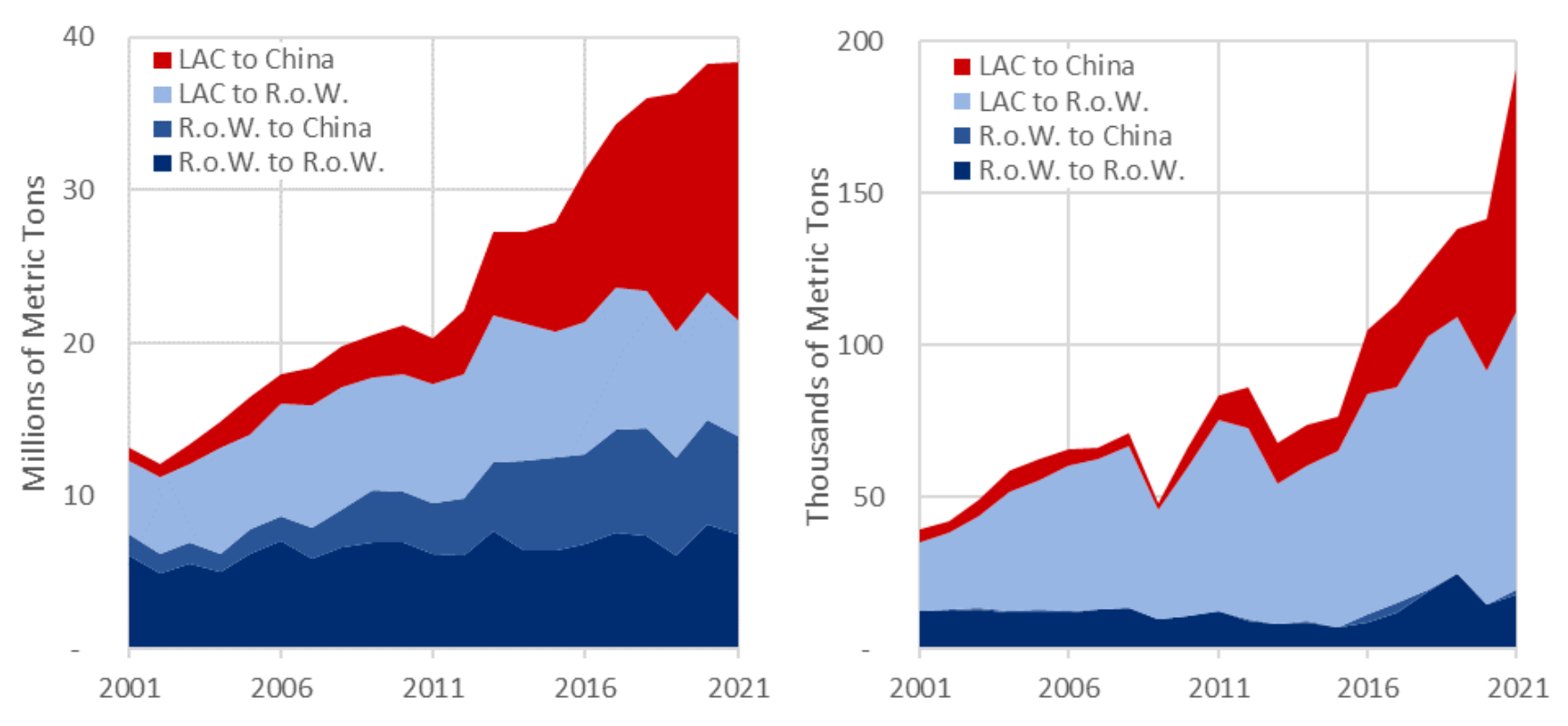

While transition minerals include a wide variety of materials, the report focuses on two emblematic examples for the China-LAC relationship: copper, a legacy mineral with a long history of extraction in LAC, and lithium, a new mineral with significant deposits in LAC. By 2050, global demand for copper is projected to have grown by up to three and a half times the production levels in 2010, while demand for lithium is projected to reach between four and a half and 40 times its 2018 production levels. The main drivers of this expansion are the deployment of renewable energy technologies, electric vehicles and connectivity infrastructure, but the speed and scale of these trends will significantly impact the trajectory of demand. These unknown variables directly affect LAC countries, as 64 percent of world trade in copper ores and concentrates and 90 percent of world trade in lithium originate in the region. As Figure 1 shows, a major portion of LAC’s exports of these minerals are bound for China. China’s demand for transition materials stems from its central position in the manufacturing and assembly stages for major renewable energy technologies, including solar and wind power.

Figure 1: Global Trade in Copper and Lithium

Copper Lithium

The importance of the LAC-China relationship to global supply chains for transition materials is undisputed, but gaps remain in terms of how several structural factors in the global economy and geopolitical landscape will affect these dynamics. First, more research is needed that links LAC countries’ positions as suppliers and China’s position as an importer. Second, the variation in LAC countries’ capacities to develop new supply chains calls for research into the opportunities and barriers for the region to leverage its potential market power. Third, the effects of slow growth rates and high inflation in a post-pandemic global economy, coupled with ongoing re-primarization in LAC, necessitate research on how the region can overcome obstacles to moving up the value chain and preventing Dutch disease. Fourth, more investigation is needed to understand the localized impacts of global geopolitical dynamics, including US-China tensions and Russia’s war in Ukraine, on different stages of supply chains.

To fill these gaps, the Working Group recommends that researchers map demand for transition materials across LAC countries for each of the different commodities, analyze how each of the structural factors discussed interact with each other and outline bottlenecks – and accompanying solutions – that may prevent LAC countries from leveraging their market power.

Fulfilling Governance Imperatives: Spurring Development and Mitigating Risks

The Working Group reviewed several policy frameworks that grew out of previous commodity booms, with lessons for promoting economic development and mitigating social and environmental risks. The literature on the resource curse suggests that strong domestic institutions can reduce problems such as slow growth, rent-seeking behavior and authoritarian tendencies. Conceived by Latin American economists, structuralist and dependency theories debate the role of trade and foreign investment in national development, emphasizing the need of industrial policies to dampen volatile commodity prices and demand. Emerging climate justice frameworks highlight the need for robust social policies to implement community-based decision-making and ease the effects of energy transitions on workers in fossil fuel industries. Today’s commodity boom also faces the risk of negative economic consequences that followed previous booms, including heightened corruption, capital flight, illegal extraction and labor exploitation, alongside weakening state capacity.

While these lessons offer an important foundation, more research is needed to clarify the extent to which they apply in the context of new supply chains, extractive patterns and social and environmental agreements. Illustrated in Table 1, the report identifies the need for research that combines upstream and downstream perspectives on governance risks, moving beyond existing research that focuses on single phases of the supply chain. Furthermore, overlapping environmental, social and economic risks require interdisciplinary research on their potential to reinforce or counteract each other. For example, lithium extraction in South America is extremely water intensive, which affects local ecosystems, water availability for local communities and the sustainability of lithium-based economic development. LAC countries have taken steps to improve regional social and environmental governance through instruments such as the Escazú Agreement and the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, but further research should explore whether shared governance challenges can provide a sufficient incentive for deeper regional integration.

Table 1: Governing Risks Along the Supply Chains for Transition Materials

The Working Group recommends pursuing research that evaluates the conditions under which policy lessons from previous booms apply in the context of new supply chains and governance arrangements, that identifies more specific policies and institutional capacities to best mitigate overlapping types of risks and that maps various stakeholders and their incentives at the local, national and regional levels.

External Stakeholders: Leveraging Expertise and Navigating Intergovernmental Cooperation

The global nature of the boom for transition materials means that LAC countries must navigate complex relationships with an increasing number of external stakeholders, including Chinese government actors, Chinese commercial actors, Western-led and Southern-led MDBs, NDBs and Western private investors. Seeking long-term energy security for China, state actors, such as China Development Bank, the Export-Import Bank of China and major Chinese state-owned enterprises have important expertise in designing and deploying renewable energy infrastructure. Likewise, Chinese commercial entities have been an increasingly important source of foreign investment in renewable energy, electric vehicles and electricity in LAC. In comparison, Western-led MDBs emphasize institutional strengthening and building technical capacity for their borrowers. Finally, Western private actors tend to be driven by short-term profit motives and have thus been a more variable source of foreign capital in LAC.

The Working Group identified knowledge gaps related to the ability of LAC countries to coordinate between these external stakeholders to leverage their complementary expertise and incentivize them to support national and regional development goals. First, Chinese state actors have reduced the size of their loans in recent years, and research is needed to identify how this new lending pattern affects financing available for LAC renewable energy infrastructure. Second, research should examine the potential impact of Chinese private firms’ increasing willingness to file investor-state-dispute-settlement claims on LAC countries’ opportunities to scale down fossil fuel projects. Third, more research is needed to clarify the potential contributions of new Southern-led MDBs and NDBs, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Brazilian Development (BNDES). Fourth, Western investors’ shifting commitments to environmental and social governance calls for research into the extent to which their interests in profiting from transition materials could overcome short-term biases.

To address these gaps, the Working Group recommends research mapping international stakeholders’ respective advantages that LAC countries can leverage in developing sustainable supply chains, evaluating the ability of LAC countries and regional institutions to navigate between competitive external actors based in China and the US, assessing the willingness of these external actors to support LAC countries’ policies and goals and exploring the role of LAC regional and national development finance institutions to coordinate external investments.

A policy-oriented research agenda that examines the structural factors affecting market conditions, the governance challenges for development and risk mitigation and the shifting roles of external stakeholders requires global collaboration. Research must bridge disciplinary boundaries between political science, economics, environmental sciences, firm behavior and other disciplines. It must incorporate cross-regional expertise from both LAC and China-based research. Finally, it must apply the tools of rigorous empirical investigation to answer questions generated by policymakers and communicate its findings to governments, inter-governmental organizations and non-governmental organizations to implement research-backed solutions.

*

Read the Report 阅读博客文章 Lee el blog Leia o blogNever miss an update: Subscribe to the Global China Initiative Newsletter.