Another $4 Billion on the Table? The Role of China’s Sinosure in Africa’s Debt Negotiations

By Oyintarelado Moses and Kevin P. Gallagher

Recent reports suggest there may be new momentum in the beleaguered Group of 20 (G20) Common Framework negotiations in Zambia and beyond.

Since its launch in 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Common Framework has been plagued by reluctance to fully engage in negotiations from private sector bondholders, who hold the majority of the debt in distressed countries, and China.

However, according to the statements from Zambia’s Ministry of Finance, China may include debt insured by the China Export and Credit Insurance Corporation (Sinosure) in debt restructuring negotiations with Zambia.

The exact impact of including Sinosure loans in the negotiations is unclear, as China’s overseas debt exposure lacks the transparency to make precise estimates of the magnitude of debt covered under such a concession.

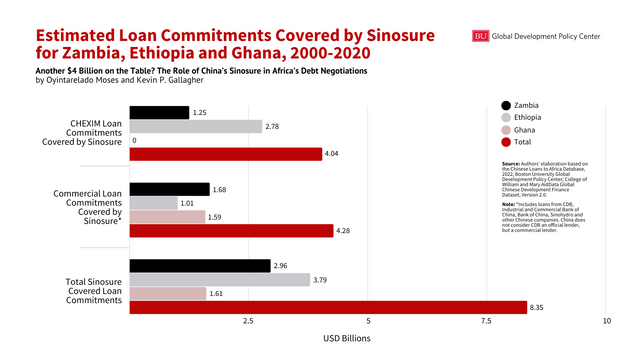

Using a combination of internal and external data sources, we estimate that including Sinosure-backed debt in the debt restructuring negotiations for Zambia, Ethiopia and Ghana could double the amount of unpaid loans that China would cover under the Common Framework from $4 billion to $8 billion. Such a move would not only be significant for China, but would also trigger the need for the private sector and other creditors to provide commensurate coverage.

Considering China’s possible inclusion of Sinosure debt, understanding the functions of financial guarantees and Sinosure’s role in China’s overseas development finance is important for understanding how China’s debt discussions could evolve.

Background

Financial guarantees and insurance agreements assure lenders that a debt will be repaid by the guarantee or insurance granting institution if the borrower refuses to repay the debt. Typically, a borrowing country can provide a sovereign guarantee stipulating they ultimately have the responsibility to repay the debt. The lender could also incorporate a guarantee or insurance from a separate institution. Some institutions view guarantees and insurance as financial instruments with the same functionality, while others define them differently. Although guarantees and insurance both ultimately protect the policy holder from losses, guarantees are indirect agreements involving the creditor, recipient and guarantor that holds the recipient to the obligation to repay a loan. Insurance policies are direct agreements between the creditor and the insurer where the creditor pays a fee, and in turn, is protected against losses tied to specific risks from the loan or equity financed project.

Sinosure, China’s state-owned export credit insurance agency, provides insurance and guarantees on export credit-related loans and investments. Sinosure has covered loans from China’s development finance institutions, the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM), Chinese commercial banks and companies. Sinosure was formed in 2001 through a merger of the export credit insurance departments of the People’s Insurance Company of China and CHEXIM. Separating the policy insurance institution through Sinosure largely mirrors South Korea and Japan’s policy insurance institutions for export credit-related loans, the Korea Trade Insurance Corporation (KSURE) and Nippon Export and Investment Insurance (NEXI).

Sinosure provides export credit and investment insurance on up to 95 percent of a loan or equity investments. This insurance can cover commercial risks, where the cause of the non-repayment is related to an inability to pay due to financial issues and political risks, where a lender may have issues obtaining repayment due to currency inconvertibility, deferred payment due to policy constraints, nationalization of a commercial asset (expropriation), breach of contract and war or civil disturbance. If the financier is unable to receive repayment or recover full returns, Sinosure will provide the financier with their payment up to the specified amount agreed to in the insurance policy, therefore assuming partial liability for repayment. Afterwards, Sinosure can try to recover its loss by legally pursuing the borrower or investee for repayment.

These functions are not unlike the World Bank’s guarantee program and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA)’s insurance policies. Sinosure’s function of insuring export credit-related loans from CDB and CHEXIM is similar to other export credit insurance agencies, such as the Swedish Exportkreditnämnden (EKN), which insures all export credit lending transactions for the Swedish Export Credit Corporation (SEK). Consequently, lending covered by Sinosure is considered “official” or “public,” as Sinosure is a government institution that is ultimately taking partial liability for repayment of the loan.

By including Sinosure-backed debt, China would be aligning its debt eligibility criteria more closely with Paris Club creditors, without having to officially become a member of the Paris Club, which China has legitimate concerns about joining. The Paris Club sees public debts as “credits and loans granted by Paris Club creditors’ governments or relevant institutions, as well as commercial credits guaranteed by them.” Many Paris Club countries have financial guarantee and insurance-granting institutions. However, most of the Paris Club countries’ loan, guarantee and insurance programs are housed in the same institution.

Estimating the Value of Sinosure-backed Debt

Publicly available data sources are insufficient to estimate the full scale of China’s loans and debt covered by Sinosure. The World Bank Debt International Debt Statistics does not disaggregate debt owed to Chinese financing institutions within its public and publicly guaranteed debt data. Internal research from the Chinese Loans to Africa (CLA) Database, managed by the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, and supplemented with data from the College of William and Mary AidData provides limited tracking on loan commitments covered by Sinosure.

Based on available data, we estimate that $8.4 billion in loan commitments to governments have been covered by Sinosure in Zambia, Ethiopia and Ghana from 2000-2020, as seen in the figure below. This amount does not equate to debt owed, as it is likely that some of these loans have been partially paid off already. However, given the average repayment expectation year is between 2030-2034, it is likely that most of the debt insured by Sinosure still needs to be repaid.

Of this $8.4 billion, 48 percent ($4 billion) are loans given by CHEXIM and covered by Sinosure. Repayment on these loans, if they are still not repaid, will be included in debt negotiations, since CHEXIM is an official lender. The other 52 percent ($4.3 billion) of the loans are from commercial loans, including those from CDB. Multiplying the amount of commercial loan commitments covered by Sinosure by 95 percent, the portion of the loan Sinosure’s policies cover, equates to $4.1 billion. For Ghana, in particular, a majority of the loan commitments covered by Sinosure primarily appear to be from commercial lenders.

We also conducted research on Sri Lanka’s loan commitments and found only one commercial loan commitment covered by Sinosure, amounting to $69 million.

In short, putting Sinosure-covered debt on the table would expand eligible debt relief by including $4 billion in commercial debt that would have otherwise been excluded from the negotiations.

Conclusion

If China is actively choosing to align eligible debt with the Paris Club definition, it may be willing to increase the amount of eligible debt for ongoing debt relief negotiations in Zambia, which could have implications for other countries indebted to China pursuing debt restructuring under the Common Framework.

On January 24th, 2022, Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Kristalina Georgieva shared that the IMF had reached an understanding with China in principle on lengthening maturities and reducing interest rates to restructure Zambia’s debt owed to China. While this update as well as a potential inclusion of Sinosure insured debt are welcome moves to provide substantive debt relief, providing debt relief on Chinese debt alone will not be enough to address the debt issues of these countries.

Without commensurate treatment from private bondholders, which hold the largest level of African government debt, additional relief from China could be used to pay bondholders, rather than to invest in the economy to recover from years of turmoil. In many countries, multilateral development banks (MDBs) hold much more debt than China, but are not participating in the Common Framework for fear of losing their preferred creditor status and AAA ratings.

The makings of a deal are coming together. If China expands the envelope of debt included in the Common Framework and compels its creditors to engage, the US and EU should put pressure on their private sector creditors and use their majority voting power at the MDBs to participate in a way that doesn’t impact their preferred creditor status or AAA ratings.

According to the Independent High Level Expert Group on Climate Finance, developing countries need to mobilize and spend an additional 6.9 percent of GDP annually from now to 2030 to be on a path to achieving their development and climate goals. Without comprehensive debt relief alongside new concessional finance and grants, these goals will be out of reach not only for indebted countries, but the world as a whole.

*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global China Initiative Newsletter.