Patrick Grange

Patrick Grange was well-known for his incredible athletic abilities and his kindness, bravery, and optimism. At 28, he was diagnosed with ALS and after his death his family donated his brain to the Boston University CTE Center where he was diagnosed with CTE Stage II/IV, making him the first American former soccer player to be diagnosed with CTE.

Patrick Grange was well-known for his incredible athletic abilities and his kindness, bravery, and optimism. At 28, he was diagnosed with ALS and after his death his family donated his brain to the Boston University CTE Center where he was diagnosed with CTE Stage II/IV, making him the first American former soccer player to be diagnosed with CTE.

Patrick’s legacy continues to live on through CTE and ALS awareness and outreach. We thank the Grange family for their generous donation and commitment to our research.

Read Mr. Grange’s story below.

From a very young age, there was no doubt Patrick Grange had incredible athletic talent. At 13 months old, he could bounce a basketball, in elementary school he excelled in baseball and was the Little League All Star catcher three years in a row, and in middle school, he was the star player on his eighth grade and club basketball teams.

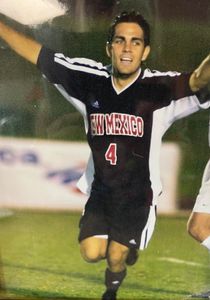

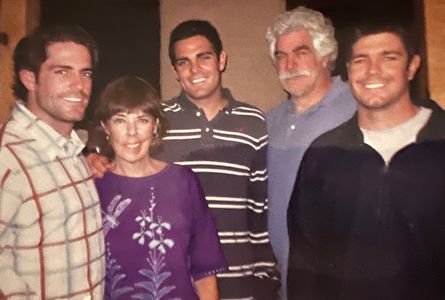

Patrick shared his love of sports with his two older brothers, Casey and Ryan, and the sport all three of the Grange boys excelled in was soccer. It was a big part of all of their lives, and Patrick began playing at just three years old, continuing through high school, including club teams and the Olympic Development Program. He then played for two years for the University of Illinois Chicago, the PD Chicago Fire team, and the University of New Mexico, where he graduated from. After college, he continued playing on numerous teams, including the semi-pro team Asylum in Albuquerque, the Premier Indoor Soccer League, and multiple adult soccer teams.

His love of soccer extended beyond just playing; he was also the assistant manager at his local indoor soccer arena and coached various teams through the Olympic Development Program, at the high school level, and Little Kickers preschoolers.

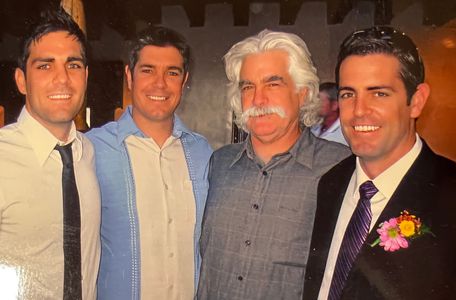

In his lifetime, Patrick was loved by many, including his parents, Mike and Michele, his brother Casey, sister-in-law Melissa and their kids Addison & Michael, his brother Ryan and sister-in-law Allison and their kids Jack and Jojo, and his girlfriend, Amanda Aragon, and her mother Veronica.

When asked to describe Patrick, his family could think of many words, including: kind, brave, optimistic, nonjudgmental, loving, and humorous. They noted his love for life and soccer and how he loved to dance and play the drums.

Neither Patrick nor his family had suspected he may be suffering from CTE and at the time, the only symptoms Patrick showed were repeated headaches, sleeping more than usual, and his family noted he sometimes didn’t demonstrate logical thinking and common sense.

At 28 years old, Patrick was diagnosed with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Over 5,000 people are diagnosed with ALS every year and the average age at the time of diagnosis is 55. Typically, individuals diagnosed with ALS have a life expectancy of 2-5 years, but Patrick died only 17 months later.

At 28 years old, Patrick was diagnosed with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Over 5,000 people are diagnosed with ALS every year and the average age at the time of diagnosis is 55. Typically, individuals diagnosed with ALS have a life expectancy of 2-5 years, but Patrick died only 17 months later.

In addition, Patrick did not have a family history of ALS, as is typical for 90 percent of those diagnosed with ALS, and due to his young age, his family suspected there was a secondary cause for Patrick’s death.

After donating his brain to the Boston University CTE Center, they learned Patrick had CTE Stage II/IV and Ann McKee, MD, described his diagnosis as CTE-induced ALS. This made Patrick the first soccer player to be diagnosed with CTE. His story became an international one, and he was featured in the New York Times, E:60 (an ESPN show), a National Geographic Explorer TV piece on head trauma, an independent film, countless newspaper articles in the United States and Europe, documentaries, books, and medical panels.

Patrick’s family reflected on their feelings after receiving the findings. In 2010, CTE wasn’t as widely known and discussed as it is now and there weren’t nearly as many resources as there are today. Though they felt comfort in knowing that there was another cause for Patrick’s death, they also experienced guilt. “He had always ‘given his all’ in every sport he played. He experienced many serious head bangs and was actually knocked out and received stitches to his head in elementary school through college,” they said. “Once we became more educated about CTE, we looked back at all the repetitive header practice Pat had done at a young age, both on his own and at team practices, and realized our lack of having him rest his brain after ‘a hard hit.’”

Patrick’s family reflected on their feelings after receiving the findings. In 2010, CTE wasn’t as widely known and discussed as it is now and there weren’t nearly as many resources as there are today. Though they felt comfort in knowing that there was another cause for Patrick’s death, they also experienced guilt. “He had always ‘given his all’ in every sport he played. He experienced many serious head bangs and was actually knocked out and received stitches to his head in elementary school through college,” they said. “Once we became more educated about CTE, we looked back at all the repetitive header practice Pat had done at a young age, both on his own and at team practices, and realized our lack of having him rest his brain after ‘a hard hit.’”

“If only we’d known.”

The Grange family continues to spread awareness for CTE and ALS and Patrick’s legacy lives on in their work. They participate in Concussion Legacy Foundation (CLF) and ALS events and fundraising. Prior to the pandemic, the Grange family hosted classes for students and athletic trainers for CLF’s Team Up/Speak Up program.

The Grange family continues to support sports and athletic activities that “establish fitness, character building, leadership, and teamwork,” but they also stress “the world needs to be educated on the dangers of head trauma, especially for our youth, while the brain is still developing and fragile. The continuing study of CTE and the promotion of brain injury awareness to help reduce the occurrence of this terrible, devastating disease deserves to be a priority for everyone!”

They recognize that more work needs to be done. “In the 11 years that we have been learning about CTE, it is wonderful that there has been so much progress and increased awareness, but there is still much to be discovered and done.”

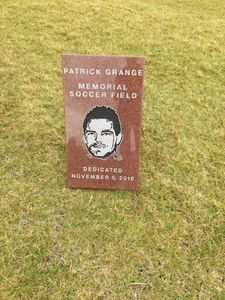

After receiving his ALS diagnosis, Patrick once told an interviewer that he had two goals: to have a soccer field named after him and that, after his passing, his experience could somehow make a difference.

In his home state of New Mexico, there is a yearly Pat Grange Awareness Day and today, young children play on the Pat Grange Memorial Field. Through continued media coverage about Patrick and his story, the Grange family says that he has, and continues, to make a difference by promoting CTE and ALS awareness.

In his home state of New Mexico, there is a yearly Pat Grange Awareness Day and today, young children play on the Pat Grange Memorial Field. Through continued media coverage about Patrick and his story, the Grange family says that he has, and continues, to make a difference by promoting CTE and ALS awareness.

That’s “what we consider the most important thing about Pat. His legacy lives on!”

The ALS statistics in this story are from the ALS Association. You can learn more at als.org.

Mr. Grange’s diagnosis was made by Dr. Ann McKee at the BU CTE Center. If you would like to support the BU CTE Center and help fund the research that makes these diagnoses possible, you can donate here.

If you or a loved one are interested in brain donation, please view our Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and brain donation brochures for more information.

This story was written by Amanda V. Cabral at the BU CTE Center. If you are interested in having a donor story written for your loved one, please reach out to her at avcabral@bu.edu.