A note from BU CTE Center director Ann McKee, MD

2023 was a momentous year for CTE research and we think 2024 will be even better. The CTE Center reached important milestones in 2023 towards furthering our understanding of CTE, identifying CTE during life, and paving the way towards the development of effective treatments.

In 2023, researchers at the BU CTE Center showed:

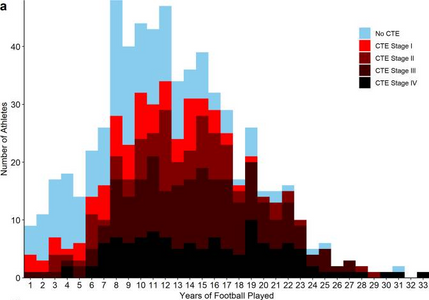

1. In football, it’s not just the number of repetitive hits to the head that create risk for CTE, it’s also the severity or strength of the hits and there are differences in risk depending on playing position.

2. After repeated head hits in contact sports and military-related activities, and in CTE, there is a break-down of the blood brain barrier and damage to small blood vessels.

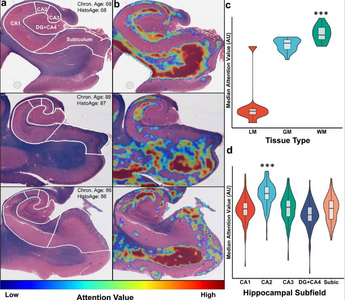

3. Tau is not the only abnormal protein that builds up in CTE, there are also abnormal deposits of TDP-43. TDP-43 accumulation in the brain is associated with scarring of the hippocampus as Hippocampal Sclerosis and promotes further cognitive decline.

4. TDP-43 deposits can be found in the retinas (eyes) of individuals with CTE, suggesting that in the future, CTE might be diagnosed at a specialized eye examination.

5. Not only does abnormal tau and TDP-43 build up in CTE, there are also important changes to the white matter. These white matter changes can occur after repeated hits to the head too, and may underlie some of the symptoms players experience, like impulsivity.

6. We are working on novel ways to evaluate white matter integrity by teaming up with basic science laboratories on the BU Charles River Campus.

7. Inflammation and gene expression changes also occur in CTE, and they are different in mild CTE compared to more severe CTE.

8. In a cross-sectional study of men with self-reported Parkinson’s disease, participation in football was associated with higher odds of having parkinsonism or a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Longer duration of football play and higher level of play were associated with higher odds of having parkinsonism or Parkinson’s disease.

9. Football and ice hockey are not the only sports where risk for CTE is related to length of playing career, the same is also true for rugby union.

10. We are starting to use artificial intelligence in the detection of brain abnormalities in CTE. Pathological evidence of brain age acceleration using AI was also significantly associated with cognitive impairment and dementia.

11. We are learning new ways to use amyloid and tau PET imaging for the diagnosis of CTE during life. Here we show that cognitive impairment in former American football players is not associated with PET imaging of neuritic Aβ plaque deposition.

12. Cognitive decline in contact sport athletes with widely ranging ages is often due to multiple, mixed pathologies, including CTE.

13. We reviewed the last 17 years of the world’s scientific research on CTE. We summarized the hundreds of contact sport athletes and others diagnosed with CTE at autopsy and reviewed the overwhelming evidence for a causal relationship between repetitive hits to the head and the development of CTE.

14. CTE can affect amateur young contact sport athletes. This study found that, among a sample of 152 young athletes exposed to repetitive head impacts (RHI) who were under age 30 at the time of death, 41.4% (63) had neuropathological evidence of CTE, a degenerative brain disease caused by RHI, most of whom were amateur players. The study included the first American female athlete diagnosed with CTE, a 28-year-old collegiate soccer player. Amateur athletes with CTE included American football, ice hockey, soccer, and rugby players, and wrestlers. Those diagnosed with CTE were older (average age at death was 25.3 years vs. 21.4) and had significantly more years of exposure to contact sports (11.6 vs. 8.8 years).

As we start our 16th year of CTE research at Boston University, I am incredibly proud of all the accomplishments of the Center and its dedicated faculty and staff. I am enormously grateful to the brain donor families, funders, monetary supporters, and all those who have helped to educate the world about CTE.

Our work is not possible without your support!

Please continue to join us in the fight to prevent, identify, and treat CTE in 2024!