Student Activism Today Is Leaving a Mark on Climate Change, Antiracism, Housing, and More

Photo by Patrick Strattner

Rising Up

Five BU students are among a new wave of campus activists, leaving their mark on climate change, antiracism, housing, and more

Student activists in the 1960s and early 1970s turned out in force to protest the Vietnam War and the draft, join the civil rights and free speech movements, and rally against on-campus recruitment by the CIA and military funding for scientific research. More than a half-century later, students are still raising their voices, for many of the same issues—such as racial justice or LGBTQ+ rights—and getting involved in movements like #MeToo and Black Lives Matter. Of the estimated 25 million Americans who took part in the nationwide protests following the killing of George Floyd at the hands of police officers in Minneapolis in May 2020, 52 percent were ages 18 to 29, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation poll.

American teens and young adults are often leading movements too—emerging at the forefront of issues like gun control, transgender rights, climate change, and campus sexual assault.

“We do seem to be experiencing a new wave of student activism,” says Charles Henebry, a College of General Studies senior lecturer in rhetoric who teaches the Kilachand Honors College course A Nation Riven: Turbulence and Transformation in 1960s America and Today. “The comparison to the 1960s is in many ways an apt one: today, as 50 years ago, our nation stands divided, and many young people are dedicating themselves to idealistic projects.”

Henebry says that while many of the issues remain the same, attitudes and methods have changed. Back then, he says, students routinely clashed with the opposition: “They occupied administration buildings and disrupted classroom education. Teach-ins replaced the standard curriculum with consciousness-raising.”

Now, activists may draw on their coursework or on campus institutions such as BU’s Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground. “Today’s activists treat the university as an ally, not an opponent,” Henebry says.

Boston University students are among this new wave of campus activists. From organizing protests to improving homes in their neighborhoods, they are leading efforts on campus and in their communities to create a more equitable world. Meet five of them.

Building Quality of Life

A working faucet can make all the difference.

That’s the premise behind Hood Renovationz, an organization that Daisy Figueroa (LAW’21) started in her native Los Angeles with the help of her longtime friends Francisco Millan and Joseph Rios in summer 2020.

Daisy Figueroa (LAW’21) says Hood Renovationz has built wall-mounted desks for kids taking classes at home during lockdown and has a long list of other projects. Photo by Patrick Strattner

All born and raised in lower-income neighborhoods in California, the trio knows firsthand the indignities and inconveniences of living in cramped, not-up-to-code houses and apartments. And with homes suddenly transformed into workplaces, schools, hospitals, and day-cares thanks to the COVID-19 lockdown, what was difficult in the best of times quickly became untenable for many. Seeing their neighbors struggling to adapt, the three friends knew they needed to help.

They created Hood Renovationz, a donor-funded operation that provides free home remodels and upgrades to people who don’t have the means to afford them or are unable to secure them from a building owner.

Back to that faucet: during one project, the team was nailing down a floorboard for a woman and her son when Figueroa noticed the woman’s sink was leaking. “I asked her, ‘Is the landlord going to come and fix this?’” says Figueroa, “and she said, ‘Oh, I told him a while ago but he hasn’t come yet.’” She told the law student that the faucet was leaking hot water, which not only wasted water, but also meant their showers were often cold. “Basic things like that piss me off so badly,” Figueroa says. “It literally took us only 20 minutes to fix it, and bam, her quality of life was exponentially increased.”

As a third-year School of Law student, Figueroa’s interests lie in real estate law, and she’s already accepted a job offer from Boston firm Goodwin after graduation. Eventually, she says, she wants to take on pro bono cases for clients facing eviction or housing discrimination, while continuing to oversee Hood Renovationz. She hopes the organization will get 501(c)(3) status by the end of the year, which will make it eligible for grants and allow them to hire a full-time director and staff.

Until that day comes, she’s trying to squeeze in as many projects as she can. The team completed seven in 2020, including building a series of wall-mounted desks for kids taking classes from home during lockdown. They have a laundry list of projects for 2021: they’re set to renovate a youth center in downtown LA, construct a handful of Little Free Libraries, and continue building and giving away desks.

“Our funding comes from friends, colleagues, and complete strangers who saw what we were doing and wanted to help,” Figueroa says. “People have offered their services, too—it’s so cool. The support has been overwhelming.”

Launch of a Movement

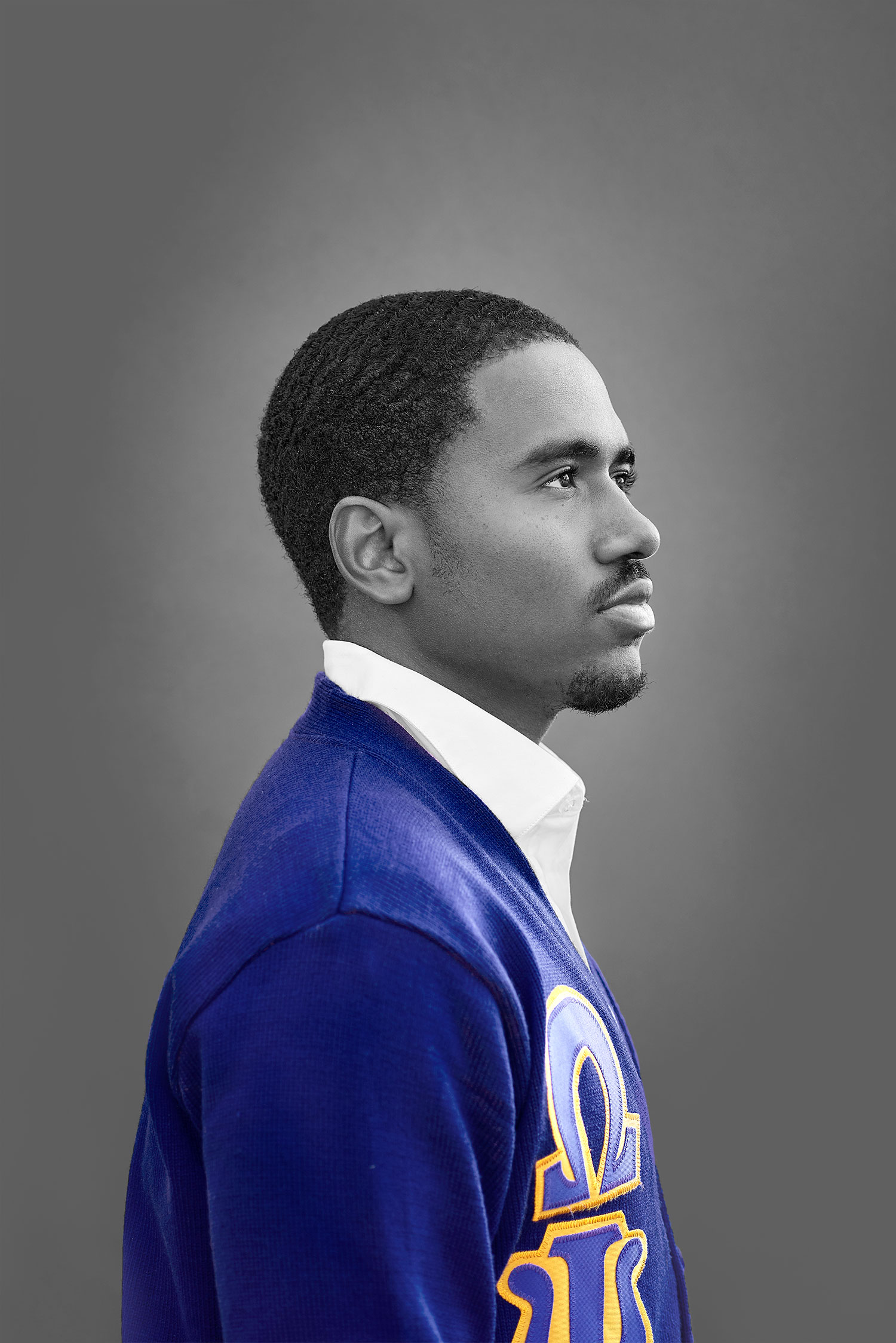

Derrick Lottie, Jr. (Questrom’21) wants to be clear: Black BU isn’t a group, it’s a movement.

Specifically, a movement launched in response to the title of conservative pundit Ben Shapiro’s 2019 speech on campus, “America Was Not Built on Slavery, It Was Built on Freedom.”

Lottie has been clarifying that point for months, ever since he and his friends Archelle Thelemaque (COM’21) and Simeon Webb (COM’21) organized a protest during Shapiro’s November speech and a summit following the controversial event. Shapiro was invited by the BU chapter of the conservative youth activist group Young Americans for Freedom (YAF).

Although he was familiar with Shapiro’s clickbaity tactics, Lottie, who had long been involved in campus life through Brothers United, a BU club for Black men, knew the effect Shapiro’s speech would have on the University’s Black community. “We figured it would rub people the wrong way,” he says, from his parents’ home in Atlanta. He and his friends called a meeting, inviting students and members of groups like Brothers United, Sisters United, Umoja (BU’s Black student union), and Girlfriends to join them in the Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground earlier that month.

There, Lottie says, emotions ran high as those gathered discussed a response. “We passed around pieces of paper and had people write down how the title of the speech made them feel, and from that, put together a statement to send to BU administration, to Shapiro’s people, and to YAF,” he explains. “And then we went around the room and asked what everyone wanted to do, and people said, ‘We should protest.’ So we started organizing one.”

They called their efforts Black BU, an umbrella students could organize under, as opposed to an official club. “Anyone who felt connected to the cause could participate,” he says, regardless of whether they were African American. With help from Thurman Center staff and Kenneth Elmore (Wheelock’87), associate provost and dean of students, Lottie and co-organizers were able to plan a route and secure a police escort for what they decided should be a silent march. (“You can’t paint us as an ‘angry group of people’ if we’re just standing there,” he says.) Approximately 200 protesters made their way from Marsh Plaza to the Track & Tennis Center, where Shapiro was speaking. Once outside, protesters, including several BU professors and members of BU Social Workers for Justice, led chants and read from the statements Black BU had prepared ahead of time.

After the protest, participants in Black BU gathered to watch Shapiro’s speech on YouTube. Lottie and Thelemaque then reached out to BU’s YAF chapter to set up a discussion, which Lottie says was “super important” to them. “In my opinion, growth happens when you have to defend your position,” he says, “and also when you can learn from someone who disagrees with you. So we thought it would be best for everyone to hear each other out, cordially.”

At the mini-summit, representatives from both sides took part in a debate moderated by Thelemaque, Lottie, and a leader from YAF, with topics ranging from free speech to the similarities between prison and slavery. “There was a lot of tension in the room, but it still went really well,” Lottie says.

He plans to continue advocating for causes that are important to him. He participated in Black Lives Matter protests at home in Atlanta last summer, and in the fall joined the Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc., which takes on charitable projects throughout the school year. He sees himself continuing to protest and give back after he graduates.

“Growing up, I didn’t have a lot of exposure to social issues,” he says. “So when I got to BU, I was able to see the world in a way that I had never seen it before. And it really has made me passionate about a lot of social issues. I want to use my voice for things I care about.”

Eat Locally

Owen Woodcock (CAS’21) spends each Wednesday trellising tomatoes. Or planting seeds, or picking fruit, or moving dirt—whatever needs to be done at Oasis on Ballou, the urban farm in Dorchester they’ve been volunteering at since the summer. “It’s one of the highest points of my week,” Woodcock says.

Woodcock started volunteering after joining the BU chapter of Uprooted & Rising, a national movement of “pods” (campus clubs) and “branches” (community groups) trying to draw institutions away from Big Food. At BU, that means lobbying the University to divest from Aramark, the contractor that supplies food for BU’s dining halls, as well as for conference centers, hospitals, and prisons across the nation. According to Uprooted & Rising, corporations like Aramark and its competitors Sodexo and Compass Group (known as “the Big Three”) shut out regional farms and vendors from opportunities such as lucrative university contracts. The movement also objects to Aramark’s contracts with correctional facilities, a practice Woodcock calls exploitative.

Uprooted & Rising aims to implement food sovereignty, which is a fancy way of saying, among other things, that the group wants everyone to eat locally. “For BU, that would involve establishing connections between the school and local food producers to get the food to campus, and then getting BU to employ all of the food workers as opposed to [being employed by] Aramark,” Woodcock says. (Currently, nonstudent Dining Services workers are employed by Aramark, not by Boston University.)

By local food producers, Woodcock means farms like Oasis on Ballou, which is a Black-owned-and-operated business. Woodcock has seen firsthand the challenges of running a food operation in Boston, at a time when Black-owned businesses are being disproportionately slammed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Part of Uprooted & Rising’s mission is to encourage and help food operations led by people of color.

While Uprooted & Rising holds special training sessions for pod members, Woodcock—no stranger to organizing in Boston, having been part of Divest BU, the Sunrise Movement, and Students for Justice for Palestine—has some ideas. Before COVID-19 hit, the BU pod hosted a couple of community-building potluck dinners with ingredients sourced from local farms. The past year derailed most in-person efforts—it’s hard to stage a sit-in when half of your pod is learning remotely—but once everyone’s back on campus, they have plans to hold a meeting with different social justice groups to build their numbers. And, they want to get more students volunteering on farms.

“One of the reasons that I’ve been deeply committed to food sovereignty is that I’ve been reclaiming my relationship with the earth,” says Woodcock from their childhood home in Jamaica Plain. “So something we want to do is to reconnect BU students with local food systems.”

An LGBTQ+ Resource Center

Arriving at BU, Christa Nuzzo (CAS’22) knew she wanted to connect with the University’s LGBTQ+ community. Nuzzo, who identifies as Latinx and queer, had quietly been out as a high schooler in New Haven, Conn., but had never sought out any queer groups for teens. College, she decided, would be her time to engage with her community. Three years later, Nuzzo has become one of BU’s most prominent advocates for LGBTQ+ rights and causes.

As a freshman, she joined Q‚ short for Queer Activist Collective, BU’s decade-strong club for LGBTQ+ students and allies. At the time, Q functioned primarily as a social group, more likely to host a movie night than, say, a meet-up to call local representatives en masse. It was fun and affirming, but she was convinced that the club wasn’t living up to its full potential.

“As I got into the groove at BU, I realized that a lot of needs weren’t being met for queer students, in terms of social advocacy and providing resources,” Nuzzo says. “I found it a little ironic that the club was named the Queer Activist Collective, but was all about social events.” She decided to join the club’s e-board and work to turn Q into a one-stop LGBTQ+ resources center.

Under Nuzzo, who was PR coordinator and vice president before becoming president, and the current board, the club is a constant source of support and knowledge. Q provides queer students with all the information they need to navigate the city and BU, from where to sign up for free queer-friendly therapy sessions to the location of every all-gender bathroom on the Charles River Campus. The club also has regular giveaways, sending members self-care kits (which include fuzzy socks and hot chocolate) and safe-sex supplies, thanks to a partnership with a local nonprofit.

Last summer, Nuzzo and outreach coordinator Ryan de Kock (CAS’22) established “Take Action Tuesdays” to make it as convenient as possible for Q members to engage in social advocacy. “We set aside an hour, put together a script [for everyone to use], and provide them with the numbers to call,” Nuzzo explains. “It’s easy to post something [on your social media] to spread information or awareness, but advocacy shouldn’t stop there. It should start there.” Since June, Q members have called Massachusetts legislators in support of releasing incarcerated people to stop the spread of COVID-19 and increasing access to HIV testing for minors, among other things.

In Nuzzo’s eyes, however, her biggest success is Q’s education arm. “I sometimes think that people don’t realize that activism can take many different forms, and they’re all effective,” she says. “You can donate and sign petitions, but you can also educate others, which is really important.” It’s so important to her that she signed up for the nonprofit Activist Academy, a fellowship program that trains participants to become effective community educators and advocates for different social issues. As a result, Q has ramped up its workshops and panels, all remote since the pandemic began. Among the offerings have been inclusivity training for the BU community, trans-friendly makeup tutorials, guest speakers, and even lessons on influential LGBTQ+ figures throughout history.

Nuzzo is excited about what she and her board members have been able to accomplish. “The growth is incredible,” she says. “We’ve been able to engage and support so many people.

“I love the work I do and am happy to help wherever I can, because I enjoy it,” she says. “I enjoy all of it.”

At the Intersection of Climate and Health

Growing up in Boulder, Colo., Quinn Adams (SPH’21) was always hyper aware of the environment. She spent most of her childhood outdoors—her family didn’t have a TV until she was 13, she says—and when she wasn’t hiking or skiing, she was often dragged to neighborhood climate-watch meetings with her parents. At the University of Colorado Boulder, she played with different majors until a lightbulb (LED, of course) went off: climate health was always in the back of her mind— why not study environmental science?

Adams was drawn to how and why climate change impacts community health, and more specifically, how those impacts are felt disproportionately by different communities, based on factors like income and ethnicity. Ultimately, her interests would take her around the world before bringing her to BU.

Upon graduating from UC, Adams headed to Washington, D.C. After an internship spent researching solutions to climate change, she landed at the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators. There, she found her groove working with federal policymakers to develop legislation around environmental justice, or the idea that no one population should shoulder an unequal burden of environmental consequences.

In September 2020, she enrolled in the BU School of Public Health’s new Population Health Research program, where she’s studying the effects of extreme heat on health outcomes in urban communities, with the goal of reducing heat-related mortalities.

“It’s all very action-oriented,” she says of her research. One project she’s working on is assessing the accuracy and efficiency of the National Weather Service’s heat-warning system. By analyzing historical data from the Weather Service, Adams explains, “we can actually see how we can improve heat-warning systems to reduce deaths.”

Adams and her cohort also sent two papers to the Biden transition team, urging the incoming administration to focus their climate policies on environmental justice and health equity.

“The climate and health field is up-and-coming, which is kind of what sparked my love for it,” Adams says. “There’s so much room for innovation. We’re trying to start conversations about so many things, the biggest being how we can help those most vulnerable to climate change.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.