It all depends on how you look at it

When you mention sponsored research at any university, what comes to mind is unprecedented competition for funding, fewer career opportunities for up-and-coming scientists, and public debate over the value of our work.

Those are big problems, no doubt.

To a major research institution like Boston University, the current unsettled research environment—and how to deal with it—is of utmost importance. So this year’s Annual Report is devoted to sharing with you just how we look at challenges, and how we get positive results.

Competition for funding is fierce.

Behind the new normalWhen it comes to sponsored research, reality isn’t what it used to be.

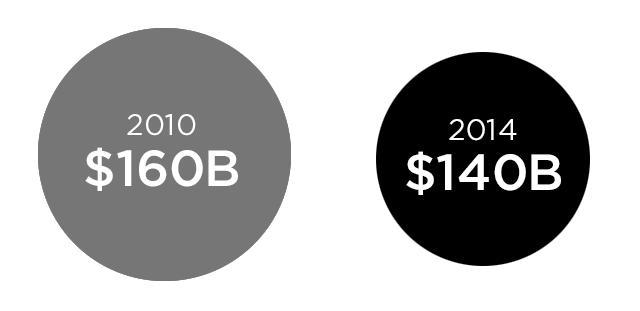

Between 1998 and 2003, Congress doubled appropriations to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the biomedical research enterprise in the US—labs, faculty positions, numbers of graduate students and postdocs—expanded accordingly. All was well. Coal was hitting the firebox at a steady clip. But then funding leveled off, and between 2010 and 2013 congressional cuts and across-the-board reductions known as sequestration kicked in. Long-term studies were halted. Jobs were lost as a result of grant terminations. And funding success was suddenly all about staying flat.

“If I had to describe the atmosphere in one word,” says Gloria Waters, vice president and associate provost for research, “I’d call it challenging, and that’s probably putting it mildly.”

Federal government spending on R&D

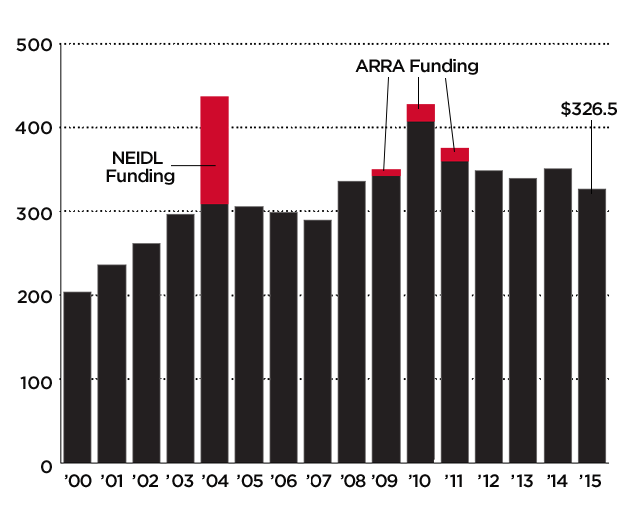

Seventy-four percent of the $326.5 million for sponsored research BU received in FY2015 (down from a 2010 peak of $407 million) came from the federal government. Another 12 percent originated in government grants and flowed to BU through other sponsors, and the rest came through alternate sources such as grants from foundations and support from private industry.

Sixty percent of the total amount went to researchers at our Medical Campus, where, according to Karen Antman, School of Medicine dean and Medical Campus provost, funding anxiety is at an all-time high. Antman says grants to the School of Medicine dropped $26.9 million in 2013 due to sequestration, although the money bounced back in 2014 when sequestration was put on hold. “These types of fluctuations in research budgets make it very difficult for our faculty to maintain momentum in their leading-edge work,” she says.

And it’s not just the limited dollars that have researchers on edge. There’s increasingly complex regulation. Data is being misinterpreted by the media and politicized by legislators. And our postdoctoral researchers are facing an unsettled future indeed.

So how did we get here—and more importantly, what are we doing about it?

Dig in, because that’s what this year’s Annual Report is all about.

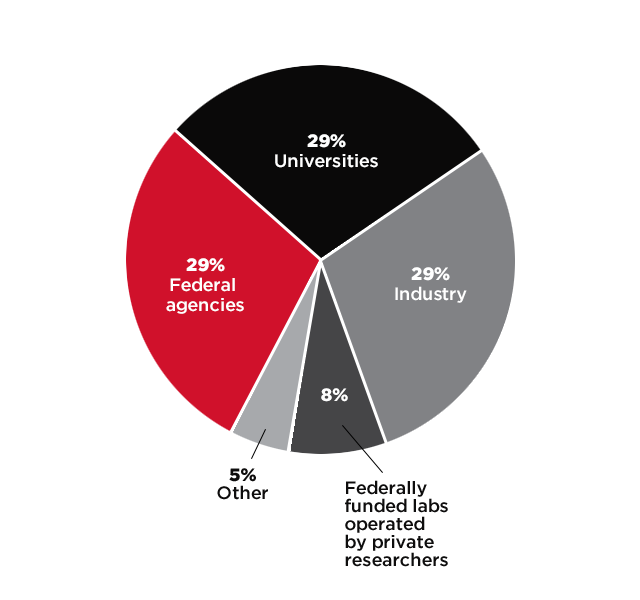

Distribution of federal research funds

A lot of administrative energy at Boston University last year was devoted not only to enhancing our research strength, but also to anticipating and adjusting for the accompanying fiscal, political, and social climates. We equipped our researchers with an enhanced tool kit, beefed up the support infrastructure for scientists and postdocs, and made the tapping of funding sources other than the federal government a top priority.

We’ve also gone against the grain by making some pretty big investments during lean times. For example, last year we broke ground on the Center for Integrated Life Sciences & Engineering, a $153 million, 170,000-square-foot facility that will result in lab space for 400 researchers from a variety of disciplines across both campuses. All around the University, the emphasis on cross-departmental collaborations has been turned way up.

The ongoing, billion-dollar Campaign for Boston University has played a big part, too, enhancing many recent research efforts, from establishing named professorships to retaining top talent to supporting entire schools on campus.

“What’s been positive about BU over the years since Dr. Brown has come on board is that we’ve hired more and more outstanding faculty and that’s how we’ve managed to keep the glass half full,” Waters says. “We’ve set the bar really high in terms of the people we want to attract and the people we want to keep here. It’s all about how much external money is available, but the best researchers are going to get their share of that money.”

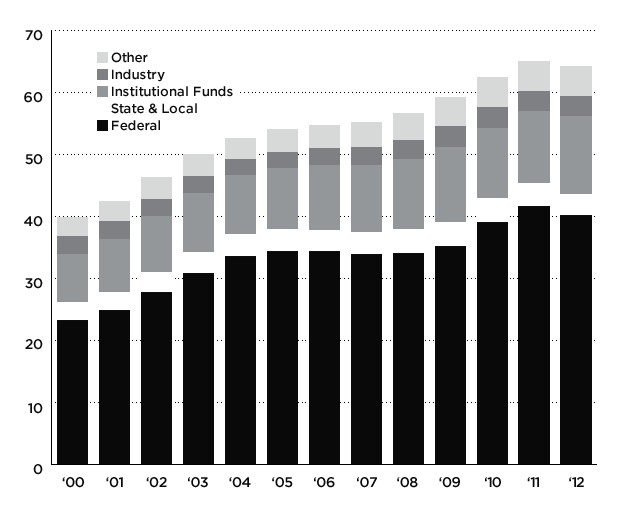

R&D funding to universities by source*

(In billions, FY2014 dollars)

*Source: National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, Higher Education R&D series, based on national survey data and includes Recovery Act funding. Courtesy of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

We’re also making sure that the important and often groundbreaking progress our folks are making reaches the right audience in the clearest language. Last year, we hosted workshops for faculty members to sharpen and streamline the way they communicate about their research. Meanwhile, our Washington, DC-based Federal Relations office has been assessing federal research priorities and helping faculty better respond to funding opportunities.

And when it comes to future explorers, healers, and inventors—our bright and talented postdocs—we redoubled our efforts to support their budding careers, whether in universities, industry, or alternate career paths.

Clearly, scientific progress has become an intricate dance in recent years, with the music speeding up and slowing down and speeding up again. Everyone’s had to learn new moves, to seek new partners. Not just for the sake of research communities everywhere, but for the sake of science, for the sake of progress.

How do We keep the research flowing?

We have some ideas

Teach Researchers how to Hunt

Simplify

Build a Better Lab

Cultivate the Next Generation of Big Thinkers

Equip Postdocs for a New World

Foster a Dynamic Student Body

Teach Researchers How to Hunt

A top priority for the vice president and associate provost for research is helping BU researchers gain advantages when it comes to securing funding.

“We’re on the verge of some important discoveries and cures in lots of areas. It’s critical we find ways to keep our trains rolling.”

If you’re a scientist relying on NIH money, we don’t need to tell you the competition for research dollars is more intense than ever. The federal agency has always been seen as the big enchilada when it comes to funding biomedical research in the United States, supporting over 300,000 scientists at more than 2,500 universities, hospitals, and research institutions, according to a report from the Congressional Research Service. But only 18 percent of NIH grant proposals are funded these days versus 25 percent 10 years ago. And while the NIH doled out some $30 billion in FY2014, that figure has barely risen since 2003.

“Staying flat is the new ‘good,' but as a major research university, we can’t be satisfied with that.”

“Staying flat is the new ‘good,’” says Gloria Waters, vice president and associate provost for research. “But as a major research university, we can’t be satisfied with that.”

Over this past year, we’ve been equipping our researchers with enhanced tool kits designed to give them an edge in the hunt for those scarce dollars. One of our sharpest instruments has been our workshop series. By bringing federal funders to BU for presentations and hands-on exercises—and sending faculty to DC to meet with agency representatives and key legislators—we are facilitating crucial relationships with government agencies. Last year, we brought National Science Foundation program directors to campus to talk to junior faculty about CAREER Awards and arranged for the USAID higher education coordinator to discuss the relationship between higher education and development. We also invited a senior official from the National Endowment for the Humanities to talk about applying for NEH grants.

In Washington, DC, our Federal Relations team focuses on national research trends and regularly connects BU researchers with key influencers and decision-makers. The team also helps place stories of BU’s funded research on agency news sites, helping nurture fruitful relationships beyond grant approvals.

In this fast-paced world, we’re building technologies to help our researchers keep up. We launched a research website last year to tell the world about the cutting-edge work taking place at BU, with a special focus on areas such as data science, global health, neuroscience, photonics, and urban health. The site also showcases our labs and facilities, profiles exciting individual researchers, and delves into our undergraduate research. An internal research site for BU faculty is currently in the works and will ultimately provide our researchers a means to easily navigate grant-application and safety-compliance issues, among other things.

By pooling resources with other researchers, the pathologist may have cracked the funding code.

One BU researcher who has seemingly cracked the funding code is Darrell Kotton, the founding director of BU’s Center for Regenerative Medicine (CReM) and a professor of medicine and pathology. How? By pooling resources—financial and scientific—with other researchers.

Within CReM, Kotton, Andrew Wilson, an assistant professor of medicine, and another scientist, Laertis Ikonomou, an assistant professor in medicine and biomedical engineering, have created an unusual three-headed lab group they informally call KIWI, for Kotton, Ikonomou, and Wilson.

All three scientists are principal investigators (PIs) who raise their own money, but they hold joint lab meetings, share ideas and equipment, and pool all their grants and resources. “That way,” says Kotton, “the science isn’t so disproportionately influenced by the waxing and waning funding of any individual PI.”

And their strategy of pursuing non-NIH funding avenues also appears to be paying off. Last year, the Massachusetts Life Sciences Center (MLSC) awarded $1.74 million to CReM to help build a new lung regeneration facility. The new facility, to be housed at CReM on the Medical Campus, will bring together academic and industry scientists from across the state to apply stem cell biology advances to developing new treatments for cystic fibrosis and other lung diseases.

Kotton’s system of pooling resources has another critical benefit: the collaboration improves the research. For instance, if one of Kotton’s technicians finds a new recipe for growing stem cells, he or she shares it with the group. “Then I don’t have to make the recipe from scratch,” Kotton says. “It saves a lot of time and effort.”

“There’s probably never been a more exciting time for science,” Waters says. “The techniques, the tools, the advancements, the new technologies. We’re on the verge of some important discoveries and cures in lots of areas. It’s critical we find ways to keep our trains rolling.”

Industry partnerships: alternate paths to funding, to impact

With the challenging landscape around federal funding for research, our faculty are increasingly collaborating with the private sector not only to secure additional funding but to see their research translated into practical applications.

Avrum Spira, a professor of medicine, pathology and laboratory medicine, and bioinformatics, and Alexander Graham Bell Professor of Healthcare Entrepreneurship, is just one example. For more than a decade, he has been chasing a big fish: a molecular test to detect lung cancer early, without invasive biopsies.

And last year, he landed his quarry, thanks not to government funding but to the molecular diagnostics outfit Veracyte, Inc. The company released a new, noninvasive test for the disease based on biomarkers Spira and his collaborators had developed. Called Percepta™, the test, when used in conjunction with bronchoscopy, identified 97 percent of the lung cancers, compared to 75 percent for bronchoscopy alone.

“Just knowing somebody may benefit from the product, that’s the most satisfying piece,” Spira says. “It’s really about impacting patient care and helping people.”

For Catherine Klapperich, associate dean for research and technology development in the College of Engineering and director of the Center for Future Technologies in Cancer Care, no truer words have been spoken. Her lab creates point-of-care diagnostics—tools that doctors and consumers can use to immediately test such conditions as high cholesterol or diagnose illnesses like strep throat.

Klapperich, who holds joint appointments—in the biomedical engineering and mechanical engineering departments—is hard at work, with a San Francisco company, on a tool that tests the amount of HIV in a patient’s blood. The results help doctors monitor the virus, decide when to start treatment, and determine if medications are working. The need for such a viral load test is critical in the developing world.

“A colleague in a South African clinic told me, ‘If people come to see me and I tell them, I’m going to take your blood, come back later to get the results, 50 percent of them just don’t come back. Something that would help immediately is if I could give that person their results right there.’”

Simplify

The virologist has been educating the community about deadly diseases like Ebola, starting with elementary school students.

Teaching researchers how to communicate to a variety of audiences has been a critical push for us. The public doesn’t support what it can’t understand.

Last year’s Ebola crisis in West Africa, which killed more than 11,300 people, was the worst outbreak on record. And for the first time, the disease made its way to US soil, claiming two lives and sickening several others. The headlines were loud, readers and viewers on edge. Then the stories faded and the public went back about its business. Until the next time, when the whole process repeats itself.

We’re working on disrupting that cycle.

Plain language is one of our most effective tools in fighting diseases like Ebola, not only in hot zones but here at home. So last year we launched an education campaign to unpack all aspects of the critical work we perform at the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL) and the nature of the illnesses we study.

“We’re trying to demystify these illnesses,” says John Connor, associate professor of microbiology and a researcher at the NEIDL. “We want to share with the community the important progress that we’re making. We think what we do is really cool work and we don’t want to hoard it.”

Connor, whose research is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, studies the tricks that viruses use to dominate their cellular hosts. He has been working collaboratively with researchers at BU and at other research institutions, with a particular focus on the Ebola virus. This includes the development of antivirals, vaccines, and point-of-care diagnostics, in collaboration with the Photonics Center and the lab of Selim Ünlü, associate dean for research and graduate programs in the department of electrical & computer engineering. Along with a group of other NEIDL researchers and several postdocs, Connor speaks to grad students, senior citizens, teens, and preteens—at the NEIDL, at schools, and at Boston’s Museum of Science.

With elementary and high school students, it usually turns into an interactive event, he says. The kids explore how researchers would be covered in a lab, how to handle a container, how to transfer solutions, what a biosafety cabinet should look like, and how samples are transported.

“It really takes the unknown out of how you work with something dangerous,” Connor says. “And they don’t have to do multivariable, complicated calculations to figure it out. It’s a lot of common sense. They come to the same answer that an industry has come to and it takes them about 15 minutes.”

“At the core of all this is we’re a bunch of nerds—and the country needs more nerds.”

Teaching researchers how to communicate to a variety of audiences has been a critical push for us over the past year, whether in front of Congress, the media, or at a retirement community. The public doesn’t support what it can’t understand. We’ve staged multiple workshops on both campuses, including a highly regarded research series inspired by actor and science enthusiast Alan Alda. The classes were so popular and effective we brought them back this year.

The bottom line is communication must be a two-way street.

“The more I’m able to talk about our work, and answer questions, the better the whole situation is,” Connor says. “At the core of all this is we’re a bunch of nerds—and the country needs more nerds.”

Let me guess: you’re a subway bacteria researcher?

It’s been called the Daily Show of science. WBUR’s new radio program, You’re the Expert, mixes learning and humor as a panel of comedians tries to guess what a guest scientist does for a living. Boston’s award-winning NPR station is owned by Boston University.

During the hour-long live show, which began airing this past summer, the comedians use questions, sketches, and games to figure out what the expert does.

“Our goal is to do for science what the Daily Show and the Colbert Report have done for news.”

“Our goal is to do for science what the Daily Show and the Colbert Report have done for news,” host and creator Chris Duffy says. “We take something that’s important but maybe a little bit dry and make it interesting and exciting and make people seek it out because it is funny and fun, and then they are also being presented with real information.”

Duffy also hopes that You’re the Expert will inspire civic involvement. “Most science in this country is funded by taxpayers,” he says. “In a very real sense, we own research, it’s ours, we paid for it. It’s important that we feel like that and we learn what it is and we feel ownership over it. We should ask about it.”

The speech, language & hearing sciences researcher learned valuable communications skills through improv workshops held on campus last year.

Express yourself

When Alan Alda’s name comes up, many people think of Captain Hawkeye Pierce or Senator Arnold Vinick. But it’s his deep passion for science—for communicating science, specifically—that turned our heads.

Alda, the longtime host of PBS’s Scientific American Frontiers, inspired the cross-disciplinary Center for Communicating Science based at Stony Brook University in his native New York. The ability to communicate directly and vividly can enhance scientists’ career prospects, help them secure funding, collaborate across disciplines, and serve as effective teachers.

The ability to communicate directly and vividly can enhance scientists’ career prospects, help them secure funding, collaborate across disciplines, and serve as effective teachers.

Last year, Assistant Dean of Academic Affairs Suzanne Sarfaty brought the Alda workshops to the Medical Campus, drawing more than 40 researchers from both campuses. “I was so impressed with the thinking behind and the power of the program,” Sarfaty says. “I knew it would be a valuable experience for our scientists and would enrich the BU community.”

The training was so popular that we invited them back. Cara Stepp, an assistant professor of speech, language & hearing sciences, participated in the second workshop. She says the exercises forced her, among other things, to reevaluate the language she uses when describing her research. “Good scientists also need to be good ambassadors of their own work, but many of us aren’t,” she says. “I learned a lot about how to focus on the audience that I’m talking to and how to formulate the message so that it specifically addresses things that the audience finds important.”

Build a Better Lab

We broke ground on a $153 million research facility that will be home to interdisciplinary centers in neuroscience, synthetic biology, and other emerging research areas.

Why invest more money in a brand-new science center? In today’s complicated world, you just can’t pause progress.

This past summer, we dug up a campus parking lot to make way for a $153 million, state-of-the-art research facility. By 2017, the Center for Integrated Life Sciences & Engineering (CILSE) will hum with questions, ideas, and solutions from the restless minds of hundreds of life scientists, engineers, physicians, and graduate students from our Medical and Charles River Campuses, as well as collaboration with researchers from other universities.

You may be asking: When times are unsettled for research funding, why invest more money in a brand-new interdisciplinary science center? But in today’s complicated world, you just can’t pause progress.

The key to that progress? Collaboration, collaboration, collaboration.

The 170,000-square-foot CILSE building will serve as a research home for the Center for Systems Neuroscience, the Biological Design Center, the Center for Sensory Communication & Neuroengineering Technology, and the Cognitive Neuroimaging Center. These interdisciplinary centers have already been tackling some of the most challenging problems in science and medicine, such as treatments for Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases, how memory works, and the root causes of autism.

Joining forces is a no-brainer, quips Christopher Chen, a professor of biomedical engineering and one of the world’s leading experts in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Fields such as synthetic biology and tissue engineering have arisen as separate disciplines; but last year, thanks to a clear vision of a collaborative synthesis, he and several colleagues convinced the University to launch the Biological Design Center, which will soon hang its sign at CILSE. “We realized that even though these two fields may involve slightly different tools,” Chen says, “they belong under one roof.”

CILSE will mix and match researchers from multiple academic fields, undergraduates, graduate students, and innovators from industry. Their labs will have no walls. They will create a community, sharing equipment, resources, and ideas across the University and beyond.

Scheduled for completion in spring of 2017, the facility is designed to qualify for LEED Gold Certification.

“Our dream really is to see neuroscience becoming more like physics, to discover elegant grand unifying theories.”

Another researcher excited to see CILSE on his business cards is the director of the Center for Systems Neuroscience, Michael Hasselmo, a professor of psychological & brain sciences. Last year, Hasselmo received a $300,000 National Science Foundation (NSF) grant to launch the new Initiative for Physics & Mathematics of Neural Systems. He says that bringing together experts from physics, mathematics, and neuroscience could lead to new mathematical models and statistical methods to interpret genomic, anatomical, and neurophysiological data on brain function.

“Our dream really is to see neuroscience becoming more like physics, to discover elegant grand unifying theories. That’s maybe overambitious but that’s the big dream.”

The digital mapmaker works with a wide range of researchers on everything from malaria hot spots in Ethiopia to the eating patterns of orangutans in Borneo.

A human world wide web

A new multidisciplinary building will no doubt move the ball down the field. Until then, interdepartment and cross-campus collaboration already happens organically across the University.

Meet cutting-edge mapmaker Sucharita Gopal. The professor of earth & environment is a renowned expert and dedicated teacher in the field of geographic information systems (GIS). Or what we might think of as “making maps with computers.” Over the past two decades, as computing power has increased, GIS has risen from an obscure method for measuring Canadian farms to a powerful technique that maps everything from the eating patterns of orangutans in Borneo to health care access in Zambia.

“All this data is only good if it addresses a societal problem. I want to solve real-world problems. I want to work with actual people to make a difference.”

Gopal’s popular classes draw young minds from public health, social work, geography, neuroscience, anthropology, and myriad other fields to learn how to turn their dry data into spectacular maps. She also has a web of connections to scientists across disciplines and around the world. On the BU campus alone, she’s worked with Susan Proctor on a School of Public Health/US Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine study mapping the incidence of Gulf War veterans’ illnesses. Gopal helped James McCann, a professor of history at our African Studies Center, find malaria hot spots in Ethiopia. And she’s working with Davidson Hamer, a professor of global health, to understand how pregnant women access health care in Zambia. “All this data is only good if it addresses a societal problem,” Gopal says. “I want to solve real-world problems. I want to work with actual people to make a difference.”

A school for our times

When the Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies opened its doors in September 2014, it welcomed nearly 1,000 students representing 14 graduate and undergraduate degree programs and majors, a core faculty of around 40, and nearly 200 affiliated faculty from an array of fields, from history and economics to anthropology and political science. It is decidedly 21st-century in its research approach and global engagement.

Housed in the College of Arts & Sciences, the Pardee School brings together faculty to support interdisciplinary research aimed at the challenge of advancing global human progress and educating the next generation of leaders who will address these issues. Endowed with a $25 million gift from Frederick S. Pardee (Questrom’54, ’54, Hon.’06), the School’s stated mission is “improving the human condition around the globe.”

Cultivate the Next Generation of Big Thinkers

The couple gave a record-breaking $50 million to the University as part of our comprehensive fundraising campaign. The gift will, in part, endow 10 faculty chairs in our business school.

We must continue to build advanced labs, attract the brightest minds to campus, and keep our established talent challenged and supported. All that takes significant investment.

A key to staying ahead of the curve in the world of research is the pursuit and retention of big thinkers. And that’s on us, not the federal government. We can’t let lean times in Washington, DC, slow us down. We must continue to build advanced labs, attract the brightest minds to campus, and keep our established and up-and-coming talent challenged and supported. Of course, all that takes significant investment. That’s where the Campaign for Boston University comes in. A part of our $1 billion comprehensive fundraising effort is dedicated to bolstering, expanding, and stimulating our research enterprise—be it through named professorships or new research facilities. And thanks to—actually, make that deep, profound thanks to—one alum and his wife, last year we took a massive leap forward.

Boston University Trustee Allen Questrom (Questrom’64, Hon.’15), and his wife, Kelli (Hon.’15), gave a record-breaking $50 million to the campaign, the largest gift in BU’s history. For starters, the donation will endow 10 faculty chairs and enable planning to establish a new graduate business program facility. It also renames the School of Management the Questrom School of Business.

“The gift is transformational, enabling us to attract outstanding faculty widely recognized for excellence in research and teaching, who will contribute meaningfully to our mission of educating ethical, innovative business leaders,” says Questrom Dean Kenneth Freeman. “We will be able to accelerate our transformation and better prepare the next generation of bold leaders.”

Questrom is retired chief executive officer of several of the nation’s largest department and specialty stores, which he helped steer out of bankruptcy, including Neiman Marcus, Macy’s, Barneys, and JC Penney. Kelli Questrom retired from a fashion promotion career to become active in civic life, focusing on preventive medicine, homelessness, and art. She co-founded the Greater Los Angeles Partnership for the Homeless, which led to the establishment of LA’s Downtown Women’s Center.

“When one looks at where investment can do the most good, you have to think of innovation in our schools. The route to earned success is to be well educated.”

The gift comes two-and-a-half years after BU announced its first-ever comprehensive fundraising effort, with a target of $1 billion. BU is the first university to set such an ambitious goal for a first campaign. The $50 million pledge—one of 134 commitments of $1 million-plus, with 14 new donors in FY2015—brings the campaign total to $870 million for FY2015. The University is now on track to meet its overall goal well before the scheduled completion date of 2017.

The Questroms’ donation also provides seed funding for the School to study the addition of a new 60,000-square-foot classroom space that will connect to its existing building. Since moving into its current home in 1996, the School has expanded significantly. The building was originally designed to accommodate 1,700 students, but now welcomes 3,500 undergraduate and graduate students.

“When one looks at where investment can do the most good, you have to think of innovation in our schools,” says Allen Questrom, “because second only to the positive influence of family values, the route to earned success is to be well educated.”

The renowned and eclectic economist joined our faculty last year, filling one of 42 professorships created so far by the campaign.

Talent magnets

One of the priorities of the campaign has been to establish professorships, both to attract the best minds from around the world, but also to cultivate faculty talent at home. So far, 42 named full professorships have been created.

One of them was filled last summer by eclectic economist Raymond Fisman, who joined the College of Arts & Sciences faculty as the first Slater Family Professor in Behavioral Economics.

“He’s a remarkable scholar. He’s creative, he’s incredibly energetic, he works in so many different directions and on so many interesting things.”

Fisman, who arrived from Columbia University, where he was co-director of the Columbia Business School Social Enterprise Program, has garnered a lot of attention for his much-cited study showing that UN diplomats from countries with a reputation for corruption, as well as anti-American sentiment, get more parking tickets than diplomats from countries considered less corrupt. He’s also co-author of Economic Gangsters: Corruption, Violence, and the Poverty of Nations and 2013’s The Org: The Underlying Logic of the Office.

“He’s a remarkable scholar,” says Barton Lipman, an economics professor and department chair. “He’s creative, he’s incredibly energetic, he works in so many different directions and on so many interesting things.”

Another faculty member tapped for a new professorship was Professor of Journalism Mitchell Zuckoff. Last year, he was named the inaugural Redstone Professor in Narrative Studies, which has been endowed, thanks to a $2.5 million gift from media magnate Sumner M. Redstone (Hon.’94).

“Not only is Mitch an excellent teacher, with great reviews every year, but he is someone who really demonstrates the craft of narrative storytelling,” says College of Communication Dean Thomas Fiedler (COM’71). “Read any of his books, and what you will see is just such an excellent example of what narrative nonfiction is.”

Home growth

The campaign has also been actively supporting BU’s young faculty through the creation, so far, of 21 Career Development Professorships, a three-year stipend designed to support scholarly or creative work, as well as a portion of the recipients’ salaries. Our awardees have been exploring everything from neural activity in animals to speech and swallowing disorders to population health in southern Africa.

Assistant Professor of Human Behavior in the Social Environment Ernest Gonzales was one of several bright minds tapped for a Peter Paul Career Development Professorship last year. He uses national-level data and sociological statistical modeling to study the impact of working during retirement years and its effect on economic disparities among older adults in the United States.

Gonzales was joined by Assistant Professor of Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics Rachel Flynn, who has been investigating chromosomal abnormalities and their contribution to premature aging and cancer in an effort to identify the causes and ultimate treatment of human disease.

Assistant Professor of Emerging Media Studies Lei Guo’s scholarship in cross-cultural journalism earned her an East Asia Studies Career Development Professorship. Guo has been exploring the role of new media technologies as agents of democratic development in China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

Equip Postdocs for a New World

They are spearheading efforts to create more and varied career opportunities for our postdocs, from positions in media to Big Pharma.

“Postdocs are in transition. We have a responsibility to make sure that we are giving them everything they need to be successful.”

Science is your life. You’ve spent the past decade as an undergraduate and graduate student, taking every biomedical class you could get your hands on. You’ve earned a PhD and logged countless 14-hour days in the lab as a postdoc, bringing home just over $40,000 a year. You’ve even published journal articles with a highly regarded researcher. But what was once a plausible reality—a faculty position at a research university—has drifted into the realm of Olympic dream, thanks to a scarcity of federal funding and too few faculty positions for too many capable postdocs.

“There’s this career progression,” says Tarik Haydar, an associate professor of anatomy & neurobiology who did his postdoc at Yale in the late 1990s. “You get a PhD, you do a postdoc, you look for an academic job, you become an assistant professor.”

That’s the traditional track, at least. But things have changed.

While the relationship between postdoc and principal investigator very much remains the engine that drives scientific momentum, established researchers are feeling their protégés’ burdens. Haydar recruited Spanish native Luis Olmos to his neural development and intellectual disorders lab at the School of Medicine (MED). Now in the fourth year of a second postdoc, Olmos has received invaluable opportunities to grow as a scientist, including a stint at Harvard Medical School’s NeuroDiscovery Center. “He’s been incredibly supportive,” Olmos says of his mentor.

Haydar hopes that Olmos and Bill Tyler, the second postdoc in his lab, will be offered faculty positions at MED. Because he recognizes the talent and potential in his two mentees, Haydar pays both well above the NIH-recommended guidelines, he says, which start at $42,840 a year and go up to $56,376 after seven years.

“These are two scientists who in the right universe should be running their own labs and starting on their own independent careers. But the playing field is very, very difficult for everybody.”

“These are two scientists who in the right universe should be running their own labs and starting on their own independent careers,” Haydar says, “but the playing field is very, very difficult for everybody.”

Just ask Chelsea Epler. The former postdoc has been there and is now dedicated to easing some of the challenges and anxieties her one-time peers are feeling.

In 2014, Epler was on her second postdoc, in biophysics. Her mentor told her she had the chops to become an outstanding independent researcher. But with constricted federal funding, Epler realized that she was unlikely to get an academic job anytime soon, if ever.

So she shifted the cube, turning toward other avenues where she could adapt her science knowledge and experience. And in February, Epler started a new job at BU as the program director for an NIH grant we won last fall, Broadening Experiences in Scientific Training. The program is intended to prepare postdocs and graduate students for science careers, both in and outside traditional academic research. Along with BU’s significantly enhanced Professional Development & Postdoctoral Affairs office, Epler’s team is working closely with industry partners to identify available biomedical research and research-related jobs and to make sure trainees have a chance at those opportunities. “I want to help other people not have the crisis I was having,” she says.

“It’s not like PhDs are driving cabs. But they may think they want an academic career, and when they see how hard it is, how much time is spent writing grants, they change their minds,” MED Dean Karen Antman says.

The neurobiologist believes it’s the responsibility of every researcher to elevate the next generation of scientists.

Thinking outside the academy

The old path has become less reliable, but thanks to a $1.8 million NIH grant BU won last fall, we’re laying down new tracks. The five-year Broadening Experiences in Scientific Training (BEST) grant was one of 17 given to universities across the country, and the funding allows us to implement a novel program that will reengineer biomedical training at the University, exposing graduate students and postdocs to research career paths on campus, as well as in nontraditional sectors such as private industry and government agencies.

“We just want people to know what they’re getting into and to open their eyes about options.”

In April 2015, the University kicked off this program with a week of seminars, panel discussions, and activities on both campuses to aid students in pursuing post-academic careers and the nitty-gritty of building industry-friendly résumés. A keynote address focused on the “Product Development Process, from Ideation to Launch.” In addition, the University launched a dedicated website and team for this initiative, with information, job postings, career development videos, and ongoing BU’s BEST programs.

“BU’s BEST is not saying that academia isn’t a good career,” says Linda Hyman, a PI on the BU’s BEST team and the associate provost for the Division of Graduate Medical Sciences. “We just want people to know what they’re getting into and to open their eyes about options. In the old system, you weren’t given the opportunity to think about anything outside of academia.”

The BU’s BEST team identifies biomedical research needs in industry and research trends beyond campus and prepares trainees for related employment opportunities. Some skills, such as critical thinking, problem solving, working in a team, and the ability to clearly communicate science, are part of learning to be a bench scientist and should carry over into jobs outside of academia. Hyman adds, “What you learn in graduate school and as a postdoc provides you with transferable skills for a variety of careers.”

Acutely aware of the new normal

“Should everyone be a postdoc? I don’t think so. We need to do a better job of directing PhD students and postdocs toward the right career paths. Not every job needs a postdoc.”

In 2014, the Professional Development & Postdoctoral Affairs office expanded to include the Charles River Campus. The PDPA offers guidance that includes nonresearch-related training and helps postdocs connect with career opportunities off campus. Heading up the new operation is alum Sarah Hokanson (CAS’05), herself a one-time postdoctoral trainee at Cornell. Her mission is simple, she says: help postdocs take charge of their own destinies.

“Postdocs are in transition,” she says. “We have a responsibility to make sure that we as an institution are giving them everything they need to be successful. If someone’s really driven in academia, what can we do to make them more competitive? Is it that they don’t have enough publications? How can we help? If someone wants to go into industry or work in science policy or somewhere else, how can we help them transfer their skills?”

One of Hokanson’s first tasks was to start compiling data on postdocs, who are connected more to departments than to the University as a whole, to help administrators develop consistent policies. She’s also wrapping up an anonymous survey on how postdocs view their training experience at BU and what skills they want to develop while they’re here. Driving much of her effort is the question being posed across the country by senior researchers, university leaders, and postdocs themselves. “Should everyone be a postdoc?” Hokanson asks. “I don’t think so. We need to do a better job of directing PhD students and postdocs toward the right career paths. Not every job needs a postdoc.”

Foster a Dynamic Student Body

The Questrom School of Business student divides her time between sinking birdies, acing exams, and building community. Who needs sleep?

Kenneth Elmore

To comprehend the vibrancy of BU’s student body, just spend five minutes on Commonwealth Avenue, says the dean of students.

“This is about a collective experience, where the individual flows into the bigger group, and where they learn more and are challenged.”

Of course, there is more to BU than just research. Another major key to an innovative campus is, obviously, the student body—that hive of intelligence, curiosity, diversity, and creativity. The vibrancy of BU’s young minds last year manifested not only in the classroom, but at homeless shelters and autism centers, in dozens of countries across the globe, on athletic fields, and in the passions of student clubs tackling water shortages and homemade rockets.

“All you need to do is stand on Commonwealth Avenue to see that richness, to see people from all over the world,” says Dean of Students Kenneth Elmore (SED’87). “They come to BU to make their fortunes, to live out their dreams, to discover their passions. It’s almost like we’ve entered Mesopotamia, where the engineers work alongside the merchants who work alongside the poets. This is about a collective experience, where the individual flows into the bigger group, and where they learn more and are challenged, and that is a good thing.”

Emily Tillo (Questrom’16) knows what Elmore means about combining strengths from all dimensions of the University.

“They come to BU to make their fortunes, to live out their dreams, to discover their passions.”

Last year, the business administration & management major helped lift the women’s golf team to a Patriot League championship while earning a 4.0 GPA along with the title of Patriot League Women’s Golf Scholar-Athlete of the Year (for the second year running). Tillo also serves on the Student-Athlete Advisory Committee, which connects BU athletes with volunteer opportunities in the community, such as registering participants for a breast cancer walk, reading to inner-city schoolchildren, staging a day of sports for autistic children, and hosting a Special Olympics swim meet. Makes you wonder when she sleeps.

“Everything at BU spreads into everything else,” Tillo says. “When I study and do well on a test, that feeds positively into my golf game. And vice versa. Obviously, we’re very privileged to be in the position that we’re in, to have these opportunities, and I feel it’s my responsibility as a citizen of the world and as a citizen of BU to give back.”

Crushing it on and off the field

While Tillo and her fellow Terriers brought home a boatload of Patriot League honors last year, our student-athletes didn’t stop at trophies and titles. They also set a new department record with a 3.08 GPA across all 24 sports and volunteered more than 3,800 hours in the community, up almost 150 hours from the previous year.

Flexing their muscles in the classroom, four Terriers were named Patriot League Scholar-Athletes of the Year. That achievement was complemented with a school-record nine athletic programs earning perfect scores of 1000 in the latest multi-year NCAA Division I Academic Progress Rate (APR). The men’s cross country team, which has tallied a perfect APR for the last six years, posted the highest team GPA with a mark of 3.41 through both semesters. Not to be outdone, the women’s cross country team paced all women’s teams, earning an overall GPA of 3.36 last year.

Of course, when it came to action on the rinks, courts, fields, and water, we weren’t too shabby last year either. Women Terriers won five Patriot League titles—in field hockey, cross country, golf, soccer, and tennis. BU’s ice women earned their fourth-straight Hockey East title and a consecutive NCAA Championship appearance, while men’s ice hockey won the Hockey East title and advanced to the NCAA Frozen Four finals.

BU Clubs: “It goes deeper.”

These days, student clubs aren’t just places to explore different interests, but to find a tribe and build community.

Take the PC Gaming Club, for example. This e-sport brings computer games to a whole new level. What was once a derided pastime now draws more TV viewers than the World Series, with gamers seen as legitimate athletes. Founded in 2011, the club competes against schools like Harvard and Tufts in local and national tournaments, and in the American Video Game League.

“I met my roommate here, my boyfriend, all these cool people whose stories I wanted to hear.”

But when former club president Yugina “Jennifer” Yun (CAS’16) learned her mother was gravely ill last year, her fellow gamers rallied around her.

“It goes deeper than just gaming,” she says. “I met my roommate here, my boyfriend, all these cool people whose stories I wanted to hear. Knowing I have somewhere I can go and feel safe is really nice.”

The gaming club is just one of 450-plus student organizations on campus. The others run the gamut, from anime and beekeeping to salsa dancing and mock trials. It’s not unusual to see a strong community-service focus. The Global Water Brigades helps build filtration systems in developing parts of Central America. Closer to home, Liquid Fun, an improv troupe, holds a 24-hour comedy marathon that benefits the Greater Boston Food Bank.

Horizons Beyond Comm Ave

Once students land on campus, the opportunities to push boundaries and exit comfort zones are endless. For many, that means studying or interning abroad—learning another culture, gaining another perspective.

Last summer, 14 students from the College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences: Sargent College spent two weeks in Peru, learning about the country’s reliance on traditional, homeopathic medicines. As part of an intensive, learning-specific trip, the group of next-gen health workers also connected with locals in remote farming villages where they became familiar with sustainable agriculture and cooking. The students in turn conducted health and hygiene workshops for area residents.

Such international opportunities—short- and long-term—are plentiful at BU. We offer more than 90 study abroad programs—in 23 countries and on 6 continents.

It’s interesting to note that research shows that students who study abroad perform better academically, are more compassionate toward peers who hail from different nations and backgrounds, and even command higher salaries after graduation. Never mind that they also get to spend a semester in places as alluring as Venice or Zanzibar.

With 40 percent of each graduating class heading abroad during their four years here (about 2,000 students annually), that’s a lot of smarts and compassion being spread throughout the world.

The View from the President's office

Read Dr. Brown’s letterIhope you walk away from this year’s Annual Report recognizing the pride we take in being a major private research university. The challenges facing the support of research don’t mean we can’t aim high. Breaking ground last year on a $153 million interdisciplinary research center only backs up that thinking. So does a dynamic community of researchers better equipped to win grants, work across disciplines, and communicate the importance of their work to anyone. Hopefully, you see things the way we do.

Also, our first-ever comprehensive fundraising campaign is making a difference. With over two years still to go, we are 90 percent of the way to our $1 billion goal.

To keep firing on all cylinders, I’m thrilled to announce that the Board of Trustees, in September 2015, agreed to boost the goal of our campaign from $1 billion to $1.5 billion and to extend its run through 2019. Most campaigns begin with a burst of activity and flatten out before picking up again at the end.

As of September 30, 2015, we’d raised $901 million—two years before the campaign’s scheduled close in 2017. During fiscal 2015, we added our 100,000th donor.

“The Board of Trustees, in September 2015, agreed to boost the goal of our campaign from $1 billion to $1.5 billion and to extend its run through 2019.”

We may have little control over federal funding priorities and allocations in Washington, DC, but, at home, we have momentum on our side along with an incredible network of alumni and friends. Thanks to their generosity and support, we’ve created 42 full professorships, 21 Career Development Professorships for promising junior faculty, and 163 new endowed scholarships for both undergraduate and graduate students. The campaign extension means our faculty members, researchers, postdocs, and students will have that much more support to carve paths, develop work, move careers forward—and help solve some of the most vexing problems facing humanity.

The theme of our campaign is Choose to be Great and by joining together on our ambitious journey as a leading private research university, we can be just that.

Robert A. Brown

FY2015: The Numbers

Crunch them hereAll things considered, the University posted a healthy Fiscal Year 2015, thanks in large part to conservative budgeting and careful day-to-day management. Our long-term strategy has been to draw financial strength from multiple areas and we managed to keep moving at a steady clip, despite continued economic volatility, federal funding cuts, and a historic winter in Boston.

The University’s operations generated a net operating gain of $119.6 million in FY2015 compared to $111.6 million in FY2014, allowing for budgeted operating reserves of $140.7 million compared to $132.5 million in FY2014. A record snowfall last winter meant an almost $7 million added expense for snow removal, which took a bite out of our bottom line. Revenue growth was a modest 2 percent because of necessarily modest tuition increases and an approximately 5 percent decrease in externally sponsored research.

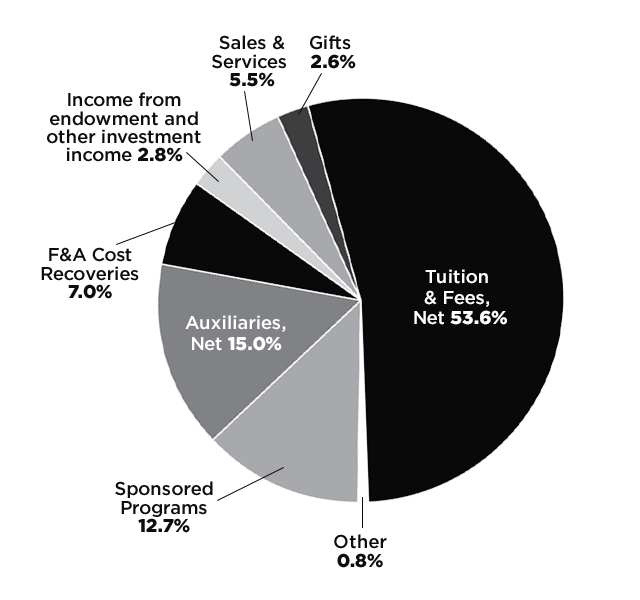

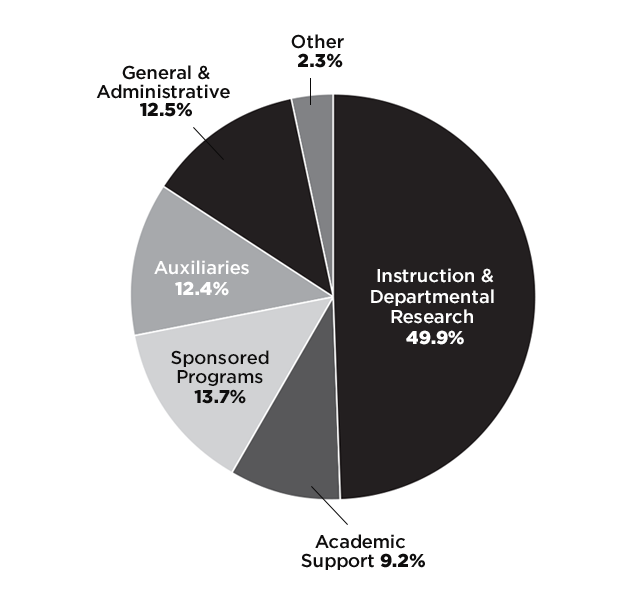

But BU was built with a big engine that fires on multiple cylinders. Our FY2015 total operating revenues were $1,762,147,000, with tuition and fees accounting for nearly 54 percent of revenues. Sponsored programs and related revenues brought in almost 20 percent. Less than 3 percent was generated by income from our $1.644 billion endowment, and only 2.6 percent came from gifts and contributions. See the charts and tables below for a breakdown of our revenues and expenses or download the Annual Financial Statements.

All in all, with a flexible and prudent fiscal approach powered by committed administrative and academic leadership, we were able to withstand the outside elements, stay on task, and position ourselves well for the coming year.

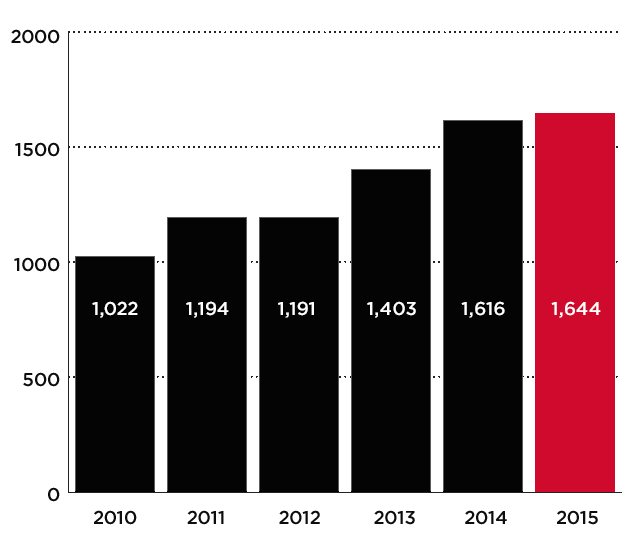

Performance benchmarks

Total assets

$ millions

Total endowment assets

$ millions

Operating revenues & expenses FY2015

Revenues

Total Revenues $1.8 billion

Expenses

Total Expenses $1.6 billion

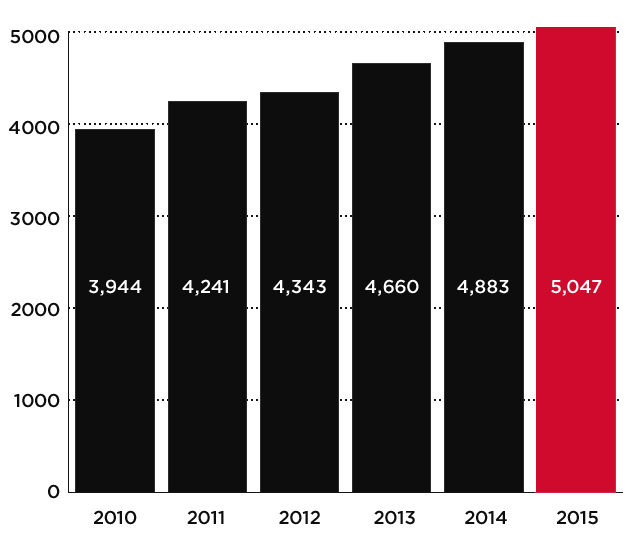

BU’s Sponsored Program Awards

FY2000–2015*

$ millions

*Excluding Financial Aid. FY2004 includes $128.0 million for the construction of the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL). Awards in FY2009–FY2011 reflect funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA).

Audited financial summary

$ thousands

Operating revenues

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student tuition and fees, net | $789,503 | $839,730 | $869,954 | $904,808 | $944,832 |

| Auxiliaries, net | 261,765 | 273,895 | 260,662 | 256,572 | 263,715 |

| Sponsored programs | 252,741 | 248,221 | 240,763 | 236,952 | 224,360 |

| Recovery of facilities and administrative costs | 130,117 | 125,896 | 123,066 | 123,547 | 122,583 |

| Sales and services | 98,383 | 94,876 | 95,110 | 108,528 | 96,070 |

| Endowment spending formula amount & other investment income | 35,276 | 35,729 | 40,643 | 44,528 | 49,251 |

| Gifts and contributions used for operations | 37,398 | 36,461 | 37,656 | 37,989 | 46,379 |

| Other income | 28,775 | 14,257 | 15,790 | 14,684 | 14,957 |

| Total operating revenues | $1,633,958 | $1,669,065 | $1,683,644 | $1,727,608 | $1,762,147 |

Operating expenses

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instruction and departmental research | $734,360 | $782,604 | $777,646 | $789,807 | $820,012 |

| Academic support | 129,241 | 125,837 | 137,628 | 145,757 | 150,885 |

| Sponsored programs | 252,741 | 242,917 | 237,408 | 235,702 | 224,673 |

| Auxiliaries | 222,853 | 217,196 | 207,269 | 196,514 | 203,038 |

| General and administrative | 150,886 | 178,412 | 216,969 | 210,311 | 205,580 |

| Other expenses | 41,313 | 40,377 | 39,597 | 37,889 | 38,390 |

| Total operating expenses | $1,531,394 | $1,587,343 | $1,616,517 | $1,615,980 | $1,642,578 |

| Net operating gain | $102,564 | $81,722 | $67,127 | $111,628 | $119,569 |

Non-Operating Activity

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undistributed investment gains/losses | $143,492 | $(35,174) | $86,899 | $166,799 | $(24,338) |

| Contribution revenue | 39,716 | 52,968 | 55,000 | 40,321 | 80,714 |

| Valuation adjustment non-core real estate | (2,552) | 7,970 | 3,976 | 5,492 | |

| Other | 78,272 | (188,409) | 78,197 | (39,182) | (72,408) |

| Total non-operating results | $258,928 | $(162,645) | $220,096 | $171,914 | $(10,540) |

| Total results | $361,492 | $(80,923) | $287,223 | $283,542 | $109,029 |