news

“Taylor Davis Selects: Invisible Ground of Sympathy”

Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston

January 31, 2023–January 7, 2024

by Theodora Bocanegra Lang

What the deaf see is what seers hear.

A place of emptiness makes sense

to those of us who stand in the door.

– Fanny Howe, At Seaport: 2023 (2023)

The title of Invisible Ground of Sympathy, now open at the Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston, is taken from Taoism scholar Chang Chung-yuan’s (1907–1988) book Creativity and Taoism (1963), which describes the blending of the discrete subject and object through interactions. As Chang writes, “The dissolution of self and the interfusion among all individuals, which takes place upon entry into this realm of nonbeing, constitute the metaphysical structure of sympathy.” The single room of the exhibition acts as this realm of nonbeing, presenting a wide range of works with both obvious and opaque affinities (fig. 1).

Invisible Ground is curated by artist Taylor Davis (b. 1959), who selected works primarily from the museum’s permanent collection. Though Davis did not include her own sculpture, she placed five narrow and vertical copper-colored mirrors around the perimeter of the gallery. The mirrors reflect passersby onto the walls as they walk around the room, collapsing the spaces between works and visitors. This mingling is echoed in many of the works on view, such as Walking Camera (Jimmy the Camera/Gift to Jimmy from Laurie) (1987) by Laurie Simmons, a photograph of a camera with legs. By anthropomorphizing the art-making apparatus, Simmons locates artists, viewers, mediums, and objects in a nebulous conflation.

Interrogating these relationships further, Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Still #48 (1979) shows the back of a young woman with a suitcase, who is looking out from the side of a road. While Sherman (b. 1954) famously uses visual cues to trigger a cinematic narrative, here seemingly of an ingénue in trouble, the scene itself could be of a number of diverse situations. Interpretation of the work relies on something already present in the mind of the viewer to project meaning. This yields a communication that fuses artist, viewer, and effect, blurring boundaries between collective and individual reception.

Extending to considerations of physical reception, Wedges (2019) by Isabel Mallet (b. 1989) is a hammered chain of nine coins made from salvaged bolts. Works from this series can be used however the possessor decides: kept on a shelf, carried in a pocket, stashed under a couch cushion, or hung on a wall. The choice to install this work on a museum wall offers a specific viewing experience. Like Davis’s mirrors, they bring the conditions of observation and the room into the work.

The exhibition probes the room as seen by the visitor’s vantage point, as articulated by poet Fanny Howe in a text commissioned for the exhibition (excerpted above). By centering viewpoint and personal experience, Howe emphasizes the individuality of looking. The inclusion of Howe’s poem in the show also muddles categorizations of visual art: it is installed like an artwork on a low pedestal with a corresponding wall label and printed copies are available for visitors to take home.

Invisible Ground presents the viewer with an array of disparate works, each an opportunity for a different kind of communication. The gallery acts as a site of building bridges, highlighting connections and differences between subject and object and between viewer and art. Davis’s decision not to include her own sculptural work itself turns a mirror on all relationships present.

____________________

Theodora Bocanegra Lang is an MA candidate in Modern and Contemporary Art History at Columbia University. She received her BA from Oberlin College in Art History. She was most recently curatorial assistant at Dia Art Foundation, where she worked on exhibitions with Jo Baer, Joan Jonas, and Maren Hassinger.

Editors’ Introduction

by Sybil F. Joslyn

Affectation, the theme we have chosen for this issue of SEQUITUR, is at once relevant and expansive in its possibilities. In our present moment, as we still feel the effects of a global pandemic, international warfare, social justice uprisings, and climate threats, we as a people face a reckoning: who do we want to be, as a nation, as a community, and as individuals? What beliefs do we hold dear in our hearts, and in what capacity do we act? What aspects of our behavior are genuine, and which are performative, or rather, an embodiment of affectation? Centrally, these questions allude to a series of inherent dualities between interiority and exteriority, surface and depth, and artifice and core, and apply to topics inclusive of human behavior, materiality, and identity. It is these dualities and topics, in addition to its timeliness, that drove our excitement to call for material related to the theme of affectation.

Affectation has long been intertwined with the complexities of human self-presentation and artistic production. In behavior, appearance, or speech, it can refer to an intentionally exaggerated display, a manufactured artifice intended to deceive. In the history of art, architecture, and material culture, these impulses toward the artificial or hyperbolic might be employed by artists, practitioners, or makers to convey a certain message, meaning, or emotion. From the fanciful gestures of the Rococo to the simplicity of geometric abstraction, affectation defines the visual world we witness and the material world we navigate. In small objects and monumental structures alike, creators have manipulated materials, shapes, and formal qualities to curate a particular experience for the observer or user. Limited to appearances, the façade of affectation often masks motivations, identities, or truths that lie beneath the surface.

Another definition of affectation resists this binary and instead speaks intimately to the relationships between object and viewer, or between artwork and observer. An affective thing has an effect on something or someone, and thus affectation can refer to an object or work of art with a perceived influence or power. Over the last half century, scholars from the social sciences, folklore studies, and humanities disciplines have begun to critically study the capacity of objects to shape human behavior.1 In their links to functionality, religion, superstition, and status, objects and artworks are potent communicators and actors within the material networks of the human world. Whether they have inherent agency or gain agency due to human belief depends on your theoretical underpinning of choice, but a simple truth remains: objects and artworks have the power to move people, both physically and emotionally. Perhaps nowhere is this power more evident than in fields that prioritize the study of visual and material culture.

For instance, certain objects embody multiple facets of affectation, like a ship figurehead captured by F.W. Powell for the Index of American Design around 1938 (fig. 1). Likely dating to the late nineteenth century, the figurehead once adorned the prow of a fast-moving sailing ship, her left hand extended outward in front of her in the direction of the boat’s movement. Dressed in Grecian sandals and flowing chiton, she exemplifies figureheads of the neoclassical type that rose to popularity during the waning years of America’s Age of Sail. She appears every bit the classical goddess, the whiteness of her body and clothing carved in deep relief in imitation of the marble fine art sculpture that permeated visual culture on both sides of the Atlantic. Yet as Powell’s drawing shows us, these stylistic qualities are surface-deep; they comprise an affectation belied by cracks that have developed in her artifice, cracks that reveal the true character of the figurehead’s making. When we look closely at Powell’s drawing, chips in the figurehead’s paint and deformities in her surface allow her wooden materiality to become evident to the viewer, and weathered patches reveal pegs and joinery where her arm and cape have been attached to her greater form. This discrepancy between appearance and material nature is only one way in which the figurehead embodies our issue’s theme of affectation.

Figureheads, in their symbolic importance, also held a certain affective power for the crews of their respective ships. They were viewed as intimately tied to the context for which they were made, an embodiment of ship name, mission, and crew livelihood. Through their position on the prow, they were viewed as symbolic navigators and as the eyes of the ship, as guardians and protectors that would help ships find safe harbor at their destinations. Manifesting the superstitious lore of her maker and the seamen, the figurehead also held an apotropaic power to ward off disaster due to storm or threat in battle and to bring good omens if her form appealed to the personified sea. Akin to lucky charms, ship figureheads were a central component of shipbuilding during America’s Age of Sail and were believed to have held the power to affect the course of perilous journeys at sea. It is both aspects of affectation—artifice and affective power—that our seven authors engage with so beautifully in this issue of SEQUITUR.

Beginning our issue, Rachel Kline’s feature essay examines the facets of affectation present in the production and reception of Mexica amentecayotl, or feather pictures, in counter-reformation Europe. Crafted by Indigenous makers and featuring Catholic imagery, the material rarity and luminosity of these featherworks appealed to the tastes of cosmopolitan European consumers who favored transcendent artistic images in line with the burgeoning drama of the Baroque. Employing a primarily decolonial lens, Kline’s essay illuminates the affective power of materials and images while emphasizing the active and singular role Indigenous craftspeople played in the development of European collecting and style. Theodora Bocanegra Lang’s exhibition review of Taylor Davis Selects: Invisible Ground of Sympathy, currently on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston, creates a meaningful dialogue with Kline’s essay. Identifying the exhibition as a contrasting collection of objects, Lang expounds upon the affective power of each of its elements. In highlighting the connections between artworks and exhibition, artworks and collection, and artworks and visitor, Lang clarifies how the elements communicate and build a bridge between viewer and art and characterizes the viewer experience as one existing between the realms of nonbeing and objecthood. While varying drastically in time period and media, both Kline and Lang address how affective power forges relationships between people and art objects.

Three of our authors take a different approach to the theme and examine affectation as a manifestation of self-fashioning or self-presentation. Through a close stylistic and contextual analysis of Sofinisba Anguissila’s Self Portrait with Madonna and Child, Emma Lazerson discusses in her feature essay the ways in which the artist displayed two modes of artistic performance and affectation in her work. By adopting contemporary conventions of courtly dress and performativity and by imitating the styles of revered artists in the embedded easel painting in her Self Portrait, Anguissila fashioned herself as both courtier and master as a preemptive gesture of belonging to a group that had yet to accept her. Michaela Peine similarly addresses the themes of affectation and self-presentation in her research spotlight but does so through an analysis of “hidden” or obscured photographic self-portraits by Jo Spence and Mary Sibande. By examining select works, Peine explores the ways each artist constructed or modified identities to present to the viewer. In this way, both Spence and Sibande embrace the multifaceted nature of identity and adopt affectation as a possible valence of the self. Rounding out this discussion of connections between affectation and identity is Ateret Sultan-Reisler, who in her exhibition review addresses the nuanced message of Philip Guston Now, a retrospective of the artist’s work that was on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston last year. Concerned primarily with providing previously minimized historical and biographical context to his work, the exhibition illuminates for the viewer connections between Guston’s lived experience and the affectation of his expressive, abstracted style. Ultimately, Sultan-Reisler tells us, Guston’s turn away from figuration to abstraction, and back to figuration, can be viewed as an artistic response to societal oppression.

Finally, two of our contributors address affectation as a symbolic manifestation of the self. In his feature essay, Samuel Love traces artistic fascination with the affected visage of the commedia dell'arte archetype of Pierrot from the turn of the twentieth century through the 1980s. By analyzing the origins of anxiety provoked by coulrophobia, or a fear of clowns, Love identifies the ways in which alternative artistic communities from the Decadents through performers of Glam Rock identified with and adopted the Pierrot mask in recognition of their marginalized status. Concluding our issue, Isabella Dobson summarizes the events of Adornment, Boston University’s Mary L. Cornille (GRS’87) 39th Annual Graduate Symposium in the History of Art & Architecture, held for the first time in person since 2019. Organized by PhD students Hannah Jew and Rachel Kline, the Symposium featured seven graduate students who presented work in two panels, “Adornment, Power, and the Collective” and “Adornment, Identity, and the Body.” Reflecting on the theme, Keynote speaker Dr. Jill Burke introduced the argument of her upcoming book, How to Be a Renaissance Woman: The Untold History of Beauty and Female Creativity, in which she makes a compelling argument that female practices of adornment during the Renaissance can be viewed as acts of empowerment and agency. While the graduate speakers addressed a wide range of topics from Ancient Assyrian burial embellishments through Chinese export embroidery in the nineteenth-century, each showed how closely the themes of adornment and affectation are intertwined. Whether to convey power, communicate identity, or relate aspiration, artists and subjects throughout time have utilized objects with affective power and carefully cultivated their self-presentation for personal, political, and economic ends. Above all, the work presented at the Symposium has elucidated how central the study of adornment is to our understanding of visual and material culture.

It is with immense gratitude that the editors of this issue of SEQUITUR thank the authors for their contributions that so thoughtfully engage the theme of affectation. Addressing subjects from sixteenth-century featherworks through the counterculture of Europe’s twentieth, this collection of essays and reflections effectively grounds the abstract theme of affectation and demonstrates the fascinating possibilities its study can yield. It is our hope that this issue will not only provide an informative and intellectually stimulating respite from these challenging times, but that it will also prompt moments of introspection on the part of our readers. By turning the mirror on ourselves, we might use these discussions of inspiration, self-fashioning, power, and identity to consider how affectation has made us who we are and who we might become.

____________________

Sybil F. Joslyn is a PhD candidate in the History of Art & Architecture at Boston University. She studies American art and material culture in the long nineteenth century, and her research explores the intersection between material and visual culture, the expression of individual and national identities, and intercultural exchange in the Atlantic World. Previously, Sybil has held internships and fellowships at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Bard Graduate Center, Hirschl & Adler Galleries, Inc., and the Winter Show. Her dissertation examines maritime salvage as object, material, and process to interrogate perceptions of identity, property, and value during America’s Age of Sail.

____________________

Footnotes

1. Scholarly publications on object agency include: Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2005), 64–86; Daniel Miller, “Materiality: An Introduction,” in Materiality, ed. Daniel Miller (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), 1–50; and Bill Brown, “Thing Theory,” Critical Inquiry 28, no. 1 (2001): 1–22.

Notes about Contributors

Isabella Dobson is a PhD student in the History of Art & Architecture at Boston University interested in the ways that eroticism, desire, and sensuality operate in paintings and prints of the female body from the Early Modern period.

Theodora Bocanegra Lang is an MA candidate in Modern and Contemporary Art History at Columbia University. She received her BA from Oberlin College in Art History. She was most recently curatorial assistant at Dia Art Foundation, where she worked on exhibitions with Jo Baer, Joan Jonas, and Maren Hassinger.

Sybil F. Joslyn is a PhD candidate in the History of Art & Architecture at Boston University. She studies American art and material culture in the long nineteenth century, and her research explores the intersection between material and visual culture, the expression of individual and national identities, and intercultural exchange in the Atlantic World. Previously, Sybil has held internships and fellowships at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Bard Graduate Center, Hirschl & Adler Galleries, Inc., and the Winter Show. Her dissertation examines maritime salvage as object, material, and process to interrogate perceptions of identity, property, and value during America’s Age of Sail.

Rachel Kline is a third-year PhD student in the History of Art & Architecture at Boston University specializing in the Italian Renaissance. With a background in anthropology, she hopes to use this perspective to explore the cultural meanings acquired by art objects and their materials circulating in the Renaissance. Rachel is especially interested in the artistic exchange between Italy and Northern Europe during the fifteenth century.

Emma Lazerson received her BA from Emory University in 2022 and is currently a first-year MA candidate in Art History at Case Western Reserve University. Her research focuses on early modern Italian female artists, contextualizing their practices in social, religious, and global theories.

Samuel Love is a PhD candidate in History of Art at the University of York. His thesis explores the carnivalesque visual culture of interwar British High Society, tracing how its engagements with baroque and Dionysian iconographies constituted a transgressive rejection of sociopolitical norms.

Michaela Peine received her BA in English and Studio Art from Hillsdale College, specializing in oil painting and portraiture. She is pursuing an MA at the University of St. Thomas studying Art History with a certificate in Museum Studies. She is currently researching contemporary artistic responses to Northern Renaissance and Baroque art, as well as decolonial educational practices in museums.

Ateret Sultan-Reisler is the John Wilmerding Intern in American Art at National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. She is working on a major retrospective of Elizabeth Catlett (2024–25). Ateret holds an MA in History of Art & Architecture from Boston University and a BA in Art History and Psychology from University of Maryland.

SIREN (some poetics)

Amant, Brooklyn, NY

September 15, 2022–March 5, 2023

by Farren Fei Yuan

The exhibition SIREN (some poetics) that was unveiled this fall at Amant in East Williamsburg, Brooklyn offers an evocative experience that dissolves the boundaries in sensory perception and artistic media. As such, it posits an alternative to the proliferation of Instagram-ready exhibitions that are focused on creating spectacles and repackaging works of art into reified commodity forms.

Founded in 2019 as a non-profit arts organization, Amant acts at once as a studio space for young artists and an exhibition space, aiming, most importantly, “to slow down the art-making process.”1 SIREN, for example, takes place in the multiple spaces of the gallery that spans across Maujer Street and envelops a courtyard garden. In contrast to exhibitions that simply present information to be received, visitors to Amant are led to make their own discoveries: inadvertently walking into the uncanny installation of a tire, an umbrella, and a school desk, or catching the sounds of bell chimes in the distance (figs. 1 and 2). These outdoor works embed poetics in the everyday.

SIREN is accompanied by a series of performances, poetry readings, “learnshops,” and creative writing workshops that take place during the exhibition period, in various spaces across the buildings. The ideas generated from these multi-disciplinary and open-ended activities become incorporated into one’s understanding of the artworks. SIREN takes place within a larger stream of everyday activities, meaning that the exhibition is “read,” “written,” and “narrated” even if it is also “seen.” SIREN encounters its audience on an individual level, through a private, slow, and multi-sensory experience. Visuality as the privileged mode of engaging with art is challenged by a range of activities that interpenetrate the gallery space.2

The dismantling of hierarchical categories of perception and knowledge has strong thematic resonance with SIREN. As Quinn Latimer writes, the siren which sounds “over land [and] across water” stands for both an emittance that establishes perceptual, linguistic, social, and territorial borders and as an expansive call that stretches across uneven terrains.3 This double-sided notion of drawing and erasing boundaries, at once disciplining and liberating, underpins the concerns of the works featured in the exhibition. The seventeen participating artists work freely in watercolor, drawings, textiles, sculptural installations, videos, and the written word, to interrogate the idea of the siren across domains and temporalities: as a figure of myths, songs, and poetry as well as of technology.

Lilian Lijn’s Queen of Hearts, Queen of Diamonds (1980), a pair of optical glass prisms whose three facets extend out through a tower of aluminum plates, are set apart, each emitting light that cuts across the space and interacts with the gallery lighting. Fetishized figures of patriarchal female archetypes and goddesses from Ancient Greek, Hindu, and Indigenous mythologies are dissipated into an assemblage of visual forms, texts, sound, volumes, and light that refuses to unify into an intelligible form. Their elusive bodies take the form of metallic pyramids under ample light (fig. 3) to flickering conical silhouettes in darkness (fig. 4), resisting capture by the objectifying gaze.

If Lijn works towards the dissolution of reified forms (both actual and figurative), other artists in the exhibition affront the visitor with sensoralities of the abject, thereby frustrating any attempt to spectacularize, reducing the exhibition into a pleasing yet inconsequential image. The most subtle example is a work by Patricia L. Boyd who has collected grease from restaurant leftovers, then used these materials to create negative casts of office items bought at a liquidation auction (fig. 5). The casts constitute a lexicon of rejects, the material evidence of the failures and excesses of contemporary society. However, these casts are embedded in the gallery walls, well above eye-level, such that their texture and form cannot be discerned. Boyd often works with “boundaries and thresholds”: the Borrowed Times series here introduces the abject (literally) into the institutional structure of the gallery and challenges the threshold of the visitor’s comfort.4

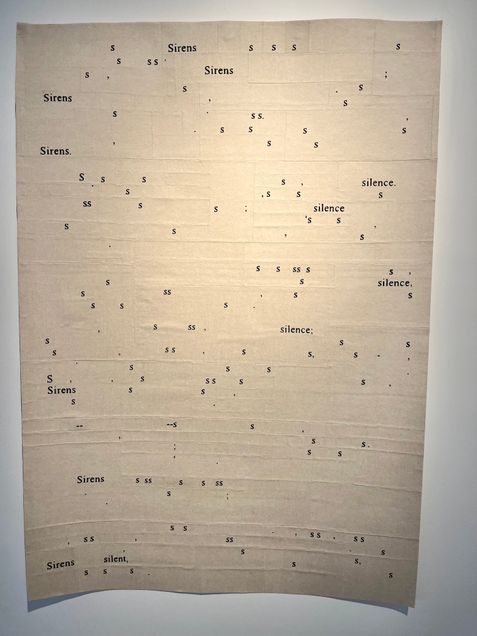

Such materiality of degeneration and decay is also palpable in Senga Nengudi’s R.S.V.P: Reverie-Combat Fatigue (1977/2011) in which hanging nylon stockings capture the material experience of the female body in its most deject, subversive state; or Nour Mobarak’s Fugue I and Fugue II (2019) where cultivated fungi cover two speakers whose multi-layered poetic recordings reflect upon history and memory (fig. 6). Addressing other dimensions of society, other artists in the exhibition turn moments of system failure into poetic allegories. Rivane Neuenschwander visualizes a possible glitch in communication in her textile piece, The Silence of the Sirens (2013) (fig. 7), a poetic constellation that emerges over a geometric grid, drifting between registers of sound and language: “silence,” “siren,” “SS,” “ssss(h).” The muted emptiness of the woven ground, and the refusal of the letters to give in to intelligible language, posit the mythical power of silence: as in Kafka’s parable referred to in the title, perhaps Odysseus survives because the sirens did not sing.

Making system failures visible exposes the problems and contradictions that would otherwise be simply smoothed over to produce an impression of successful operation. The artist collective Shanzhai Lyric, for example, composes poems out of counterfeit goods, consumer detritus, and theft practices (fig. 8). In Iris Touliatou’s HAPPINESS, 2018-2022 (to Laurie) (2022), a small display screen is held in place on a wall by the frame of an egg carton (fig. 9). Captions pop up at intervals, synchronized via a custom-made software to the speed of incoming notifications from the artist’s unread Gmail inbox. The continuous generation of signs that overflow in an incoherent narrative dramatically plays out the fracturing of today’s user-consumer’s sense of self. These are further played out on a phallic formal structure that is made uncanny by empty carton slots, the shadow cast on the wall, and the reflection of the viewer on the dark screen. The comfortably distant and secure position of the viewer that the spectacle relies on for its ideological functioning is disturbed.

SIREN posits the un-form, the abject, and the glitch as ways to practice contemporary poetics. The subversive power of the works is subtly embedded in their poetic beauty, like the deceptive charm of sirens, confronting the visitors and thereby resuscitating their experience. In a society of hyper-mediation, we need more exhibitions like SIREN which provoke us to reexamine and rethink common perceptions.

____________________

Farren Fei Yuan is an aspiring art researcher and critic. She graduated with a first class in BA in History of Art from The University of Oxford and is currently pursuing an MA in Modern and Contemporary Art: Critical and Curatorial Studies at Columbia University. Yuan has a special interest in image-text relations and post-war visual culture in the global context.

____________________

Footnotes

1. “About,” Amant, accessed December 10, 2022, https://www.amant.org/about.

2. This challenge to the assumptions underlying our conceptions of different activities is a strategy Rancière puts forth as an alternative to the rigidified practice of mixed media and interdisciplinarity. See Jacques Rancière, “The Emancipated Spectator,” in The Emancipated Spectator (London: Verso, 2021), 22.

3. Quinn Latimer, “SIREN (some poetics) [exh. guide],” Brooklyn, New York: Amant, 2022.

4. Patricia L. Boyd, “Contact Barrier: Patricia L. Boyd,” by Dora Budor, Mousse Magazine, July 5 2021, https://www.moussemagazine.it/magazine/patricia-l-boyd-dora-budor-2021/.

Following Institutional Critique Inside the Library

by Levi Sherman

When artists in the 1960s began challenging systemic authority, it seemed any cultural heritage institution—library, archive, or museum—could be a target of what would become known as Institutional Critique.1 The same period heard the first rumblings of today’s “digital convergence,”2 or the collapse of libraries, archives, and museums into repositories of information, accessed by users with little interest in the distinctions between these types of institutions.3 Yet even as librarians, archivists, and museum registrars blurred into “information professionals” in the 1960s, artists would develop a very different relationship with libraries than with archives and museums. My current research triangulates this unique artist-library relationship through the art historical framework of Institutional Critique, the cultural history of libraries, and the discourse of information science.

I hope to complicate the art historiography of Institutional Critique and glimpse what has been lost when the distinct purposes and practices of libraries, archives, and museums blur into information or institutionality writ large. These blurred boundaries haunt Institutional Critique from its inception in the journal October, which drew heavily from Foucault’s rather abstract understanding of the archive.4 It seems no coincidence that Henry Pisciotta writes from the perspective of a working librarian when he posits an alternative timeline of Institutional Critique, which peaks with the archival turn of the 1990s.5 Where art historians like Blake Stimson distinguish between a generation who tries to hold public institutions accountable and one who tries to redirect private institutions, Pisciotta shows that artists never stop trying to hold libraries to their mission.6

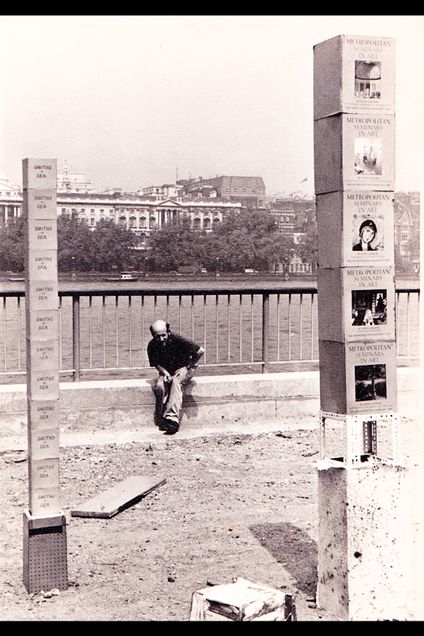

John Latham naturally figures into Pisciotta’s study of the Institutional Critique of libraries. Latham staged his spectacular book-burnings, Skoob Tower Ceremonies (1964–1968), at several institutional sites, like the British Library.7 Figure 1 illustrates another Skoob Tower Ceremony staged in London’s South Bank, with a similar civic architectural backdrop. But few later artists adopt Latham’s approach. Where Latham treats the library—like the museum and the courthouse—as a shallow signifier of culture and authority, later artists perform their critique from inside the institution, often with its permission and support.8 These artists understand the library as an exercise of authority but also democracy. They engage in a nuanced immanent critique that addresses how libraries operate rather than what they represent symbolically.

Beneath its stereotypically neoclassical façade, the modern public library has never been a centralized authority like the archive or museum, which share its spectacular architecture of power. Indeed, library history reveals continued frustration with this decentralized governance within national organizations like the American Library Association.9 Public libraries are accountable to taxpayers, serve amateur researchers, and prioritize information dissemination over preservation or connoisseurship. In other words, the anti-institutional pressure that Stimson associates with “new technologically enabled forms of peer-to-peer social organization” shaped the public library long before digital convergence began.10

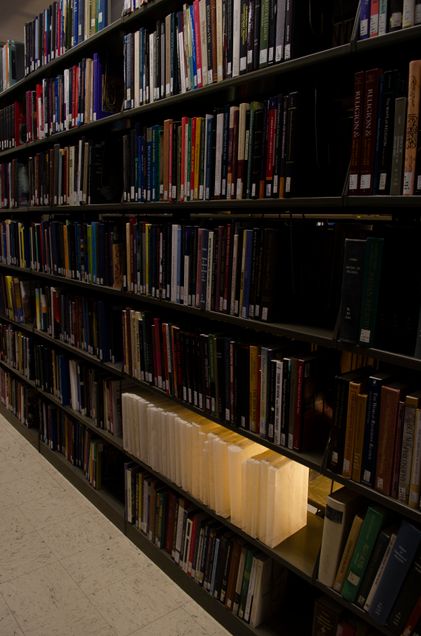

Artists need not intervene in the library’s spectacular trappings—its outward signifiers of culture and authority—because members of the community remain agonistically engaged with the institution’s inner workings. Indeed, the everyday interactions between the library and its patrons are generative points of departure for many artists. One example is India Johnson’s Negative Theology (2019–2020), which converses with a specific library as a site and set of practices (fig. 2).11 Johnson checked out a university library’s complete selection of books on the subject of negative theology and filled their spots on the shelves with fabric casts during the check-out period.12 Thus, the location, scale, and duration of Johnson’s installation are determined by the library’s classification scheme, acquisition plan, and checkout policy. Whereas Institutional Critique artists tended to approach art museums from the position of artists rather than patrons, Johnson's visit mirrors that of a typical user; anyone can remove books from a library shelf and keep them, thus altering the space within the constraints of the site.

Art history has been better at theorizing generalized modes of site specificity than addressing the operations of a specific site like a public library. My research seeks to understand how artists engage with libraries and their communities of readers by using the tools of library historians like Wayne Wiegand, a people's historian of libraries: the public and mundane evidence of policies, annual reports, meeting minutes, and letters to the editor.13 Reading Johnson’s immanent critique in the context of library history reveals the decentralized yet highly institutionalized terrain where people continue to encounter actual democracy, not just architectural and artistic spectacle of democracy found outside of the library.

____________________

Levi Sherman is a PhD student in Art History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. With a background in design and interdisciplinary art, he maintains a studio practice and co-operates a small press. Levi’s research interests include walking art, artists’ books, and the broader intersection of contemporary art, books, and libraries.

____________________

Footnotes

1. According to art historian Blake Stimson, “institutions were understood to be the means by which authority exercised itself” and so represented the system of “illegitimate authority” and control, which artists previously located in authoritarian figures like heads of state. Blake Stimson, “What Was Institutional Critique?” in Institutional Critique: An Anthology of Artists' Writings (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011), 22.

2. Wayne A. Wiegand, Part of Our Lives: A People’s History of the American Public Library (United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2015), 193–194.

3. Cecilia Salvatore, “Libraries, Archives, and Museums in the Twenty-First Century,” in Libraries, Archives, and Museums: An Introduction to Cultural Heritage Institutions Through the Ages (Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2021), 251–260.

4. In framing Institutional Critique, Benjamin H.D. Buchloh and Hal Foster tend to address the idea of the institution rather than its operation. Foster’s 1996 essay “The Archive without Museums” exemplifies this approach, which invokes the library as a Borgesian, Alexandrian thought experiment. Foster does so by blurring Foucault’s respective treatments of the library and the archive, which themselves tend toward the abstract. See Hal Foster, “The Archive without Museums,” October 77 (1996): 97–119.

5. Henry Pisciotta, “The Library in Art’s Crosshairs,” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 35, no. 1 (2016): 2–26.

6. Stimson,“What Was Institutional Critique?,” 37.

7. Elisa Kay, “John Latham,” Flash Art International 44, no. 280 (October 2011): 64–67.

8. Pisciotta discusses examples by Mel Chin, George LeGrady, Clegg & Guttman, and others which reveal different strategies for maintaining a critical edge while collaborating with the institution.

9. One telling example was the ALA “Library Bill of Rights,” which emerged during the Second World War to combat censorship and promote free inquiry. Library historian Wayne Wiegand notes that actually implementing the LBR was “almost always messy, often impossible, and professional consensus… was hard to discern.” Wayne A. Wiegand, Part of Our Lives: A People’s History of the American Public Library (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 166.

10. Stimson, “What Was Institutional Critique?,” 32.

11. India Johnson, “Negative Theology,” India Johnson, accessed October 18, 2022, https://indiajohnson.hotglue.me/?sitespecific/

12. Negative theology, or the study of the divine through what it is not, is no doubt a pun, but the subject also relates to Johnson’s research into the intersection of religion, language, and book art.

13. As municipally funded institutions with public boards, library records are generally more available than those at museums and other private institutions.

Curses as Crowd Control: Tourist Folklore at Pompeii

by Rowan Murry

In 1922, news of Howard Carter’s rediscovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb took the world by storm. In February 1923, excavators reburied and secured the tomb while archaeologists catalogued their findings and made plans for the next excavation season. It was around this time that the excavation’s financier, who had been present at the opening of the tomb, died mysteriously.1 In actuality, Lord George Herbert, the fifth Earl of Carnarvon (1866–1923), had contracted blood poisoning from an open wound caused by a mosquito bite.2 The press, seizing on the story of the Earl’s “mysterious” death, developed a sensationalized narrative of the so-called “mummy curse,” a legend that has pervaded the field of Egyptology ever since.3

The Egyptian mummy curse is an example of what I will refer to as “tourist folklore.” The term describes the perceived phenomenon of misfortune brought upon tourists who steal from or vandalize cultural heritage sites and the perpetuation of these myths by local inhabitants or stewards of these sites.4 Often, tourist folklore myths are bolstered, or sometimes even invented, by heritage site stewards to discourage theft or vandalism.5 This essay examines one example of how custodians of heritage sites manipulate public superstition to protect their sites from thievery and vandalism associated with tourism, especially in cases where funding and implementing physical security measures is impossible.

A valuable example of contemporary tourist folklore operates at the ruined city of Pompeii, an archaeological park near Naples, Italy (fig. 1). Pompeii is an important example not only because of its notoriety as a "dark tourist site"—a site associated with death and trauma—but also because it is one of the most visited UNESCO sites in the world, with approximately three million visitors per year.6 Using frameworks offered by Marcel Mauss and Michel Foucault, this essay utilizes the cultural heritage site of Pompeii as a means to explore the tourist folklore phenomenon. While the example of tourist folklore at Pompeii is not representative of all types of heritage sites and folklore, it provides an example through which to discuss themes of magic, dark tourism, and spectacle.

A discussion of the origins and function of tourist folklore requires an introduction to “contagion magic,” a dominant force fueling superstition and mysticism at Pompeii. The concept of magical contagion is best summarized by French sociologist Marcel Mauss in his book A General Theory of Magic:

The idea of magical continuity, realized through the relationship between parts and the whole or through accidental contact, involves the idea of contagion. Personal characteristics, illness, life, luck, every type of magical influx are all conceived as being transmitted along a sympathetic chain….However, magical contagion is not only an ideal which is limited to the invisible world. It may be concrete, material and in every way similar to physical contagion.7

In other words, once a person comes into physical or spiritual contact with an object, person, or entity, its essence, properties, or spiritual links are transmitted to the person. Contagion curses imply that the physical act of touching and subsequently removing an object from its home initiates spiritual contagion. The physical act of theft provokes bad luck caused by the object, the land, or a deity, which afflicts the offender and sometimes even their family and friends.

Pompeii shares similarities with the tourist folklore and mummy curses associated with the excavations of ancient Egyptian tombs. Anthropologist Anna Wieczorkiewicz dissects this societal fascination with ancient bodies and death, and concludes that “mummies, skulls, and skeletons become our fetishes in seeking meaning” about our own mortality.8 At Pompeii, visitors are immersed in a past world of paganism, debauchery, and destruction, where they play the roles of archaeologist, discoverer, adventurer, ancient Roman, and tourist.9 As a result, Pompeii becomes a dark tourist site where death and destruction are commodified and fetishized. This “quasi-religious mystique” of Pompeii is a crucial factor in a tourist’s decision to steal from the site.10 Visitors to dark tourist sites “seek tangible symbols of the place, the memory, meanings and experiences,” where material objects offer a medium through which they can reflect and channel complicated feelings or difficult memories.11 In addition to these motivations, I propose that the act of stealing artifacts from dark tourist sites like Pompeii is an act of defiance against mortality. It is a direct challenge to the destruction and death one must face at Pompeii—it gives the thief an illusion of control, both literal and metaphorical, over natural forces.

In October 2020, the media amplified the sensationalized story of a “cursed” Canadian woman who had visited Pompeii in 2005.12 She stole “two white mosaic tiles, two pieces of [amphorae], and a piece of ceramic wall” as souvenirs from her visit.13 In 2020, the woman returned the artifacts along with a letter, which stated that she “wanted to have a piece of history that couldn’t be bought,” and which she claims plagued her with bad luck and “negative energy” for 15 years.14 In the letter, she cites examples of her misfortune, including a breast cancer diagnosis and financial loss.15 She implies that the bad luck associated with the artifacts was the direct result of desecrating such a powerful site of trauma, loss, and destruction; it was a disrespectful act which activated Pompeii's magical contagion.

Luana Toniolo, Archaeological Officer of Pompeii, has estimated about 200 returns of stolen material to Pompeii over the past ten years, both resulting from and in anticipation of the potential curse.16 Toniolo suggested that artifacts which have been removed from their findspot lose their “strength as historical objects,” a quality which is crucial for the park’s mission of preservation and education.17 The park’s desire to deter tourists stealing and displacing artifacts led to a fascinating exhibition on the site’s tourist folklore. In response to the 2020 letter regarding the curse, curators at the Antiquarium of Pompeii compiled a temporary exhibition of letters and returned “cursed” objects. According to CNN, the purpose of the exhibition was anthropological, as a documentation of tourist interactions at Pompeii, but the underlying message is clear: do not steal from the site or else.18 News and media coverage of the alleged curses and subsequent exhibition further sensationalized the tourist folklore narrative maintained by the park’s staff.

The curse of Pompeii further perpetuates this air of mystique offered by dark tourism, and the stewards of Pompeii are using it to their advantage. By displaying returned cursed objects in the Antiquarium and in the media, the custodians of Pompeii are simultaneously creating further interest in the site while protecting it from future damage. The curse brings more visitors to the park, but the threat of magical contagion keeps them in line. At a place like Pompeii, which spans 170 acres, it is impossible to always surveil guests. This is where the curse plays a crucial role. In Foucault’s panopticon, a prisoner surveillance system which functions as a metaphor for modern society’s structure, the threat of constant visibility provokes self-regulation.19 At Pompeii, the threat of the curse plays the singular authoritative role which influences the behavior and social norms of the masses. Fear of this authority creates a system of self-discipline and social control—it is a means of surveillance without a physical entity.

At Pompeii, tourists’ desires to steal from the site stem from uncomfortable encounters with death, destruction, and dark tourism. The curse relies on its mystical associations with paganism and death at the site to both enrapture visitors and the media and ensure the site’s future protection from vandalism and theft. The media spectacle created by the curse serves Pompeii in various ways by preventing destruction and theft, serving as cost-effective security measures, and bringing more attention, visitors, and money to the site. In the face of mass tourism, curses can help communities and custodians regain some semblance of authority over their own heritage and history. However, in some cases, tourist folklore further perpetuates stereotypes and misrepresentations of ancient culture and beliefs. This is true for Pompeii, which is often portrayed in the media as debaucherous and esoteric. It is vital to consider the ways tourist folklore operates in different contexts and how this can positively or negatively impact our collective understanding of history and cultures.

____________________

Rowan Murry received her BA in Art History from the University of Mississippi and is currently pursuing an MA in Museum Studies at New York University. She is particularly interested in Ancient Roman art and archaeology, ethical collecting, and interactive technologies for physical and virtual exhibitions.

____________________

Footnotes

1. Mark R. Nelson, “The Mummy’s Curse: Historical Cohort Study,” British Medical Journal 325, no. 7378 (December 21–28, 2002): 1482.

2. Roger Luckhurst, The Mummy’s Curse: The True History of Dark Fantasy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 8.

3. Luckhurst, The Mummy’s Curse, 9; “George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon,” The British Museum, accessed December 12, 2022, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG53843.

4. Joyce D. Hammond, “The Tourist Folklore of Pele: Encounters with the Other” in Out of the Ordinary: Folklore and the Supernatural (Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1995), 159.

5. Other examples of sites that have a history of tourist folklore in order to discourage theft and vandalism include The Petrified Forest in Arizona and Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park.

6. The Palgrave Handbook of Dark Tourism Studies (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2018); “Visitor Data,” Pompeii Archaeological Park. This number does not account for any COVID-19 pandemic closures during 2020–2022. The most recent data comes from 2018.

7. Marcel Mauss, A General Theory of Magic (London: Routledge, 2001), 81–82.

8. Anna Wieczorkiewicz, “Unwrapping Mummies and Telling Their Stories” in Science, Magic, and Religion: The Ritual Processes of Museum Magic (New York: Berghahn Books, 2004), 68.

9. Wieczorkiewicz, “Unwrapping Mummies and Telling Their Stories,” 66.

10. Dorina Buda and Jenny Cave, “Souvenirs in Dark Tourism: Emotions and Symbols,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Dark Tourism Studies (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 719.

11. Buda and Cave, “Souvenirs in Dark Tourism: Emotions and Symbols,” 719–720.

12. Jack Guy and Nicola Ruotolo, “Tourist returns stolen artifacts to Pompeii after suffering ‘curse’ for 15 years,” CNN, October 13, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/pompeii-artifacts-returned-scli-intl/index.html.

13. Guy and Ruotolo, “Tourist returns stolen artifacts.”

14. Guy and Ruotolo, “Tourist returns stolen artifacts.”

15. Guy and Ruotolo, “Tourist returns stolen artifacts.”

16. James Gabriel Martin, “Curious tales of why tourists have been returning ‘cursed’ items to Pompeii,” Lonely Planet, October 26, 2020, https://www.lonelyplanet.com/news/pompeii-cursed-objects-tourists.

17. “About Us,” Archeological Park of Pompeii, accessed December 12, 2022, http://pompeiisites.org/en/archaeological-park-of-pompeii/about-us/.

18. Guy and Ruotolo, “Tourist returns stolen artifacts.”

19. Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Vintage Books, 1979).

Paved Paradise: The Concrete and the Stuplime at Parc des Butte-Chaumont

by Madeline Porsella

“The modernization process is complete, and nature is gone for good.”

– Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991)

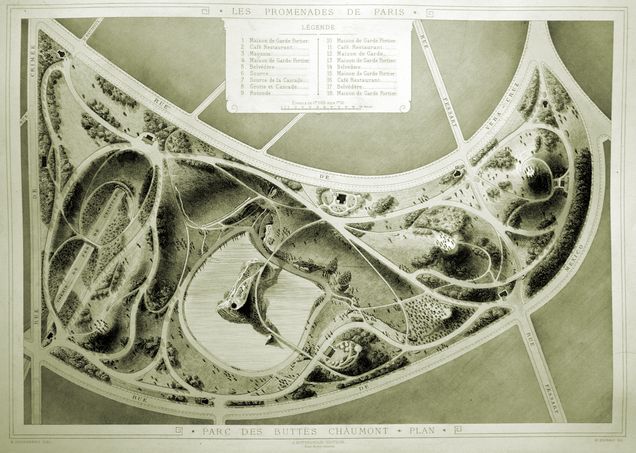

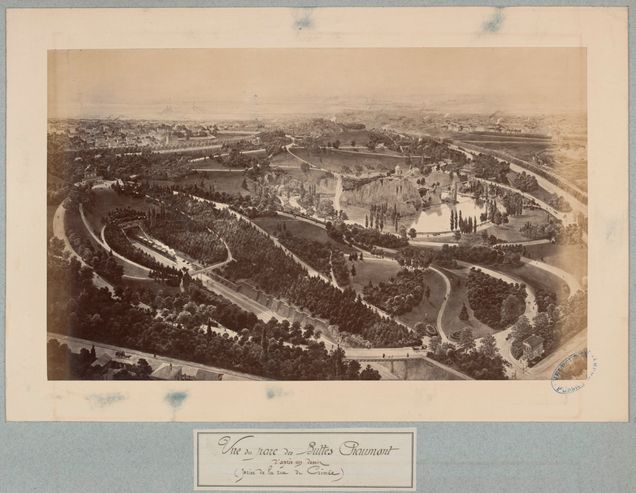

When the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont (Buttes-Chaumont Park) opened in conjunction with the Exposition Universelle on April 1, 1867, the city of Paris was in the midst of a legendary makeover undertaken in 1853 by Napoleon III, leader of the French Second Empire (1851–1870), and headed by Georges-Eugene Haussmann (1809–1891), prefect of the Seine. Medieval Paris’s narrow, winding streets, deemed unhealthy and unhygienic by nineteenth-century standards, were razed and replaced by wide boulevards, green spaces, and fountains. These changes, known as Haussmannization, created a new culture of display in Parisian public life, a “spectacularization” that reconfigured the relationship between citizens and the urban landscape. A rapidly developing technology, concrete, helped remake the city at every level beginning with the sewers that allowed wastewater to flow unseen under city streets. Haussmann and Jean-Charles Adolphe Alphand (1817–1891), who designed the Parc des Buttes Chaumont, used the site to experiment with concrete’s aesthetic possibilities. Decimating the existing landscape, they transformed an old refuse dump into a green space punctuated with picturesque vignettes (fig.1). Concrete allowed them to simultaneously subordinate and reproduce the environment, creating an artificial landscape that Ulf Strohmayer has called a “second nature.”1 The park’s overall effect was a simulacrum of nature “made naturally wild,” a controlled experience of pristine nature achieved via a total artificiality.2

Today, we live with the legacy of the resulting shift in our relationship to the landscape: romantic awe at nature’s unfathomable scale, the Kantian sublime, gave way to the fantasy of human domination, remaking the natural world as a containable and reproducible cultural product. Updating the sublime for the twenty-first century, Sianne Ngai coined the term stuplimity: the sublime meets tedium and repetition to the point of boredom and stupefaction.3 Nature writer Robert Macfarlane uses the term to describe the daily barrage of information regarding climate change, “the aesthetic experience in which astonishment is united with boredom, such that we overload on anxiety to the point of outrage-outage.”4 Due in large part to concrete fantasy-scapes in the legacy of the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, we are confronted daily with statistics on humanity’s detrimental impact on the environment.5 Calamitous destruction is reduced to a data set.

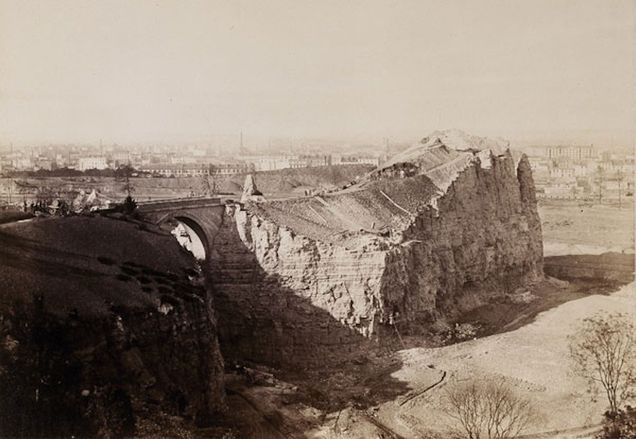

The Parc des Buttes-Chaumont was a new kind of spectacularized public works project. Breaking from the conventions of previous world’s fairs and exhibitions, installations at the 1867 Exposition Universelle were not limited to the Palais de l’Exposition; they bled out into the streets, putting renovated Paris on display.6 The concurrent debut of the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont demonstrates how sprawling the exhibition truly was. Named for the bleak topography that had previously occupied the site, Chauve-mont or bald hill, the park had an equally bleak history: for nearly 600 years it had housed the gallows where the French king not only hung criminals, but left them on display as a warning to any would-be delinquents. After the 1789 Revolution, it was used as a quarry and refuse dump (fig. 2). The seedy location was likely chosen for the contrast it provided with Alphand’s romantic vision, demonstrating the state’s modernity and power by paving over the site’s undesirable past.7 To any of the fair’s eleven million visitors, the awe-inspiring views and romantic features were only enhanced by knowledge of the gory wasteland that had preceded them.8

Ironically, the romantic natural feeling of the park was created with innovative artifice. Alphand envisioned a wild landscape punctuated with moments of the “engineered picturesque.”9 In order to evoke untouched nature, engineers employed technologies that eradicated the existing environment: concrete, landscaping, and water pumps. While Alphand’s functional concrete constructions, such as an artificial lake bed, were invisible to visitors, he also deployed the material as a surface treatment for innovative decorative features—cast faux bois (imitation wood) fences, rock faces, and stalactites were all made using concrete.10 Carefully designed vistas were visible from the elliptical paved paths snaking through the park (figs. 3 and 4).

In one striking example, Alphand transformed a pre-existing lacuna in the granite, a result of quarrying, into a grotto complete with faux stalagmites and stalactites and a cascading waterfall (fig. 5). A space that had previously been nothing but cut stone now presented itself as a natural marvel. Ulf Strohmayer argues that this reconciliation of technology and landscape is “not so much an act of concealment but of acceleration….”11 In the period eye, the park’s design, a “landscape full of simulacra…modeled on repetitions,” was a triumph of humankind’s capabilities.12 To be able to reproduce the grandeur of the natural world was to play god. This power was put on full display in the park, creating a spectacle of technology and labor, the twin engines of modernization, masquerading as untouched nature. Concrete is not disguised; “it is resolved… into its products—which can thus celebrate both nature and human ingenuity.”13 A new landscape was formed, one that recast nature and culture as oppositional forces while demonstrating that, in truth, they produce one another.

The Parc des Buttes-Chaumont anticipates the end-product of this accelerating cycle of growth and modernization—modern, and even postmodern, Paris. Peter Collins, author of Concrete (1959), locates a shift from aristocratic favor for carving and masonry to a taste for democratic modes of building—casting and molding—in the late eighteenth century.14 Broadly, this reflects the changing values of the time, an acceleration towards a mass-consumer society. The widespread adoption and use of concrete aligned with a shifting social structure fomented by urban environments; cities industrialized, grew, and modernized to meet demand as people flooded in to provide labor. These new denizens became consumers of the goods produced under industrial conditions. By the mid-nineteenth century, concrete technology was ready to rise to society’s needs, supporting the new infrastructure of both mass production and mass consumption.

In the intervening century and a half, we have poured concrete at a monstrous pace. Concrete continues to lay the foundations for high-rises, highways, suburbs, subways, and urban sprawl, the infrastructure of modern life. It is second only to water in rankings of the world’s most used building materials.15 Due to a carbon-intensive production process, concrete is responsible for about eight percent of global carbon emissions.16 China is by far its largest consumer on earth, releasing 858.23 million tons of CO2 in 2020.17 This is largely the result of amped-up development projects designed to demonstrate state authority by dominating nature. In this way, China builds upon the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont’s legacy.

The Three Gorges Dam, one such infrastructure project, exemplifies how concrete use has developed globally from the nineteenth century to the present day (fig. 6). The concrete hydroelectric gravity dam in Hubei Province was ironically conceived in an effort to limit greenhouse gas emissions from coal. It has had an immeasurable impact on the surrounding environment—increasing risk of landslides, accelerating extinction of indigenous wildlife, displacing over a million Chinese residents, and flooding archaeological sites that once sat on the river’s banks. It is so massive that its weight is estimated to have increased the length of earth’s day by .06 seconds.18

Archeologist Christopher Witmore uses the Three Gorges Dam, as imaged in Edward Burtynsky’s photographs, to describe the “Hypanthropos,” his neologism for our current epoch, defined by calamity and the often monstrous and unanticipated consequences of human projects.19 Witmore’s term is offered to replace the more commonly used “Anthropocene,” our current geological period defined by human impact on the stratigraphic record. In a 2018 paper on concrete and ice, anthropologists Tim Ingold and Cristián Simonetti identify concrete as “the most obvious candidate for marking the origin of the Anthropocene.”20 In their argument, concrete is the material that afforded humans enough power over the landscape to impact the geological record.

The term Hypanthropos is playfully constructed to remind us that, though the Anthropocene is marked by human activity, we are not in control. It is a double-entendre: the prefix hyp- recalls both the Greek prefix hyper-, meaning “excess, overwhelming being,” and hypo-, meaning “a sense of being under, beneath, [or] below something.” Humans, Witmore explains, are “suspended above and below”; they both overwhelm their environments and are contained within or overwhelmed by them.21 Hypanthropos’s multiple meanings displace the anthropos, the human, in their larger ecological context. The Parc des Buttes-Chaumont and the Three Gorges Dam are unique to the Anthropocene, human-made objects with massive environmental impacts. They reinvent nature “as contrast—with culture, with symmetry,” when, in reality, no such opposition exists.22 Nature is paradoxically both produced by and a container of culture, both hypo and hyper, above and below.

Witmore uses Burtynsky’s images of the colossal concrete dam as a medium for illustrating our suspension. If the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont modeled concrete’s usefulness in creating controlled landscapes, then contemporary concrete infrastructure projects, which have caused immeasurable and unpredictable ecological destruction, show the fallacy in that promise. Witmore reminds us that though the scale and impact of the Three Gorges Dam are astonishing, "Over the last two decades more than half of the concrete ever produced was mixed, poured, and set—4.3 billion tons were produced in 2014 alone. As for ‘water control and utilization’ projects, more than one large dam has been built every year for at least the last 60.”23 This is the legacy of Alphand’s experiments in concrete.

When the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont opened, it solidified the illusion that culture could dominate and tame nature, turning it into a reproducible commodity. Concrete was the critical technology in establishing the park’s “second nature,” an environment of artificiality.24 However, our current state of climate catastrophe has proved that illusion, or rather delusion, to be dangerously false. No matter how convincingly we cast imitation stalactites, they will never be more than cheap reproductions. Projects like the Three Gorges Dam remind us that our technological know-how does not elevate us above the natural world. No amount of concrete will remove us from the planet’s delicate ecosystem.

____________________

Madeline Porsella is an interdisciplinary historian and artist based in New York, NY. She studied studio art at Bard College and is currently pursuing her MA in Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture at the Bard Graduate Center. Her research is focused on the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries where her areas of interest include the incorporation of new technologies into art and design, new media, the relationship between science and the occult, and cultural constructions ranging from memory to the gendered body.

____________________

Footnotes

1. Ulf Strohmayer, “Urban Design and Civic Spaces: Nature at the Parc Des Buttes-Chaumont in Paris,” Cultural Geographies 13, no. 4 (October 2006): 570.

2. Strohmayer, “Urban Design and Civic Spaces,” 565.

3. Sianne Ngai, "Stuplimity: Shock and Boredom in Twentieth-Century Aesthetics," Postmodern Culture 10, no. 2 (2000). doi:10.1353/pmc.2000.0013.

4. Robert Macfarlane, “Generation Anthropocene: How humans have altered the planet forever,” The Guardian, April 1, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/apr/01/generation-anthropocene-altered-planet-for-ever.

5. Christopher Witmore, “Hypanthropos: On Apprehending and Approaching That Which Is in Excess of Monstrosity, With Special Consideration Given to the Photography of Edward Burtynsky,” Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 6, no. 1 (2019): 144.

6. Anne O’Neil-Henry, “Introduction,” Dix-Neuf 24, no. 2–3 (2020): 115–122.

7. Abigail Susik, “Aragon’s ‘Le Paysan de Paris’ and the Buried History of Buttes-Chaumont Park,” Thresholds, no. 36 (2009): 68.

8. Ann E. Komara, “Measure and Map: Alphand’s Contours of Construction at the Parc des Buttes Chaumont, Paris 1867,” Landscape Journal 28, no. 1 (2009): 35–36.

9. Ann E. Komara, “Concrete and the Engineered Picturesque the Parc des Buttes Chaumont (Paris, 1867),” Journal of Architectural Education 58, no. 1 (2004): 5.

10. Komara, “Concrete and the Engineered Picturesque,” 6–9.

11. Strohmayer, “Urban Design and Civic Spaces,” 565.

12. Strohmayer, “Urban Design and Civic Spaces,” 569.

13. Strohmeyer, “Urban Design and Civic Spaces,” 566.

14. Peter Collins, Concrete: The Vision of a New Architecture: A Study of Auguste Perret and His Precursors (New York: Horizon Press, 1959), 19.

15. Man-Shi Low, “Material Flow Analysis of Concrete in the United States,” (MS thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2005), 11.

16. Justin Davidson, “Concrete Doesn’t Have to Be an Ecological Nightmare,” New York Magazine, December 3, 2021.

17. Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser, "CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions," OurWorldInData.org, accessed December 17, 2021.

18. Witmore, “Hypanthropos,” 139.

19. Witmore, “Hypanthropos,” 143.

20. Simonetti Cristián and Tim Ingold, "Ice and concrete: solid fluids of environmental change," Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 5, no. 1 (2018): 27.

21. Witmore, “Hypanthropos,” 143.

22. Strohmeyer, “Urban Design and Civic Spaces,” 565.

23. Witmore, “Hypanthropos,” 139.

24. Strohmeyer, “Urban Design and Civic Spaces,” 570.

Notes about Contributors

Colleen Foran is a PhD candidate studying African art at Boston University. Her research focuses on contemporary West African art, particularly on public and participatory art in Ghana’s capital of Accra. Prior to coming to BU, Colleen worked at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art.

Katherine Gregory is an Art History PhD candidate at the University of Texas at Austin. A scholar of American art history, she is writing her dissertation on Robert S. Duncanson’s landscape paintings. She is the recipient of a 2022–2023 Luce/ACLS Dissertation Fellowship.

Sarah Horowitz is a PhD candidate in the history of art and architecture at Boston University. Her dissertation research focuses on the intertwined art, architectural, and urban histories of postwar American performing arts centers. Prior to pursuing her doctoral studies, she was the curatorial assistant at the Picker Art Gallery and the Longyear Museum of Anthropology at Colgate University. She received her MA in Art History from the University of Massachusetts–Amherst and BA in Art History and Museum Studies from Marlboro College.

Rowan Murry received her BA in Art History from the University of Mississippi and is currently pursuing an MA in Museum Studies at New York University. She is particularly interested in Ancient Roman art and archaeology, ethical collecting, and interactive technologies for physical and virtual exhibitions.

Darcy Olmstead is an MA candidate in Modern and Contemporary Art History (MODA) at Columbia University. Her current thesis seeks to explore artists’ publications in digital time by examining four recent projects by artists who utilize the form of the book to reflect on a world of chaos and hyper-culture brought about by digitization. She is originally from Fayetteville, Arkansas, and holds a Bachelor of Arts from Washington and Lee University.

Madeline Porsella is an interdisciplinary historian and artist based in New York, NY. She studied studio art at Bard College and is currently pursuing her MA in Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture at the Bard Graduate Center. Her research is focused on the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries where her areas of interest include the incorporation of new technologies into art and design, new media, the relationship between science and the occult, and cultural constructions ranging from memory to the gendered body.

Levi Sherman is a PhD student in Art History at UW—Madison. With a background in design and interdisciplinary art, he maintains a studio practice and co-operates a small press. Levi’s research interests include walking art, artists’ books, and the broader intersection of contemporary art, books, and libraries.

Farren Fei Yuan is an aspiring art researcher and critic. She graduated with a first class in BA in History of Art from The University of Oxford and is currently pursuing a MA in Modern and Contemporary Art: Critical and Curatorial Studies at Columbia University. Yuan has a special interest in image-text relations and post-war visual culture in the global context.

Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition

Museum of Modern Art, New York

October 30, 2022–March 4, 2023

by Katherine Gregory

Upon hearing the name Meret Oppenheim (1913–1985, Germany), any person who has taken an introductory art history course will picture her fur-covered cup Le Déjuner en Fourrure (1936) (fig. 1). This sculpture has come to stand for Oppenheim’s entire oeuvre and, as such, has retroactively established her in the public consciousness as the feminist leader of the Surrealists. Oppenheim herself, however, resisted such gendered categorization of her fifty-year career that produced hundreds of works, ranging from paper collages to hard-edged abstractions to figurative painting and experimental photography. Oppenheim did not want to be thought of as just a woman artist or just a Surrealist, and thus she declined to be interviewed for or have any works reproduced in the definitive survey Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement (1985). The recent traveling exhibition Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition, currently at MoMA, aims to transform that popular understanding of the artist, showcase the breadth of her output, and let her diverse artworks speak for themselves (fig. 2).

Organized chronologically, the exhibition opens with Oppenheim’s precocious debut with the Surrealists in Paris at age eighteen. Her early assemblages like Fur Gloves with Wooden Fingers (1936) are both feminine (with polished red nails) and outrageously grotesque (disembodied and eerily lifelike). These works invite her viewer to imagine touching and tasting these uncanny objects that simultaneously repel any possibility of sexual pleasure. In terms of the idea of “spectacle,” few artists seem more relevant than Oppenheim, whose titanic output has played with viewers’ ideas of the absurd, the horrific, the titillating, and the beautiful. The early Surrealist works (in the first rooms of the exhibition) exemplify the movement’s fascination with dreams, the subconscious, and the power of both to transform the world through enthusiastic creative expression.

The exhibition then discusses Oppenheim’s prewar figurative painting, paying close attention to the artist’s engagement with fairy tales and legends. In 1937, Oppenheim left Paris because of the growing political tension in Europe. After fleeing Paris for rural Basel in the lead-up to World War II, she painted The Suffering of Genevieve (1939) (fig. 2), based on a fable about a banished young woman. The artist painted a nude, armless woman, circled by her golden hair, floating through the black night. The helpless yet beautiful woman (defined by Anglo-European standards of female perfection) embodies the spectacular disempowerment of female artists, celebrated for their feminine grace yet disarmed and thus unable to make unpleasant artistic or political statements. The curators suggest Oppenheim felt kinship with this character as an exile far from her creative home in Paris.

Although Oppenheim experimented with different media and expressive painting styles throughout her life, she often returned to familiar themes or stories. In 1954, Oppenheim began renting a new studio space in Bern and producing work that engaged with the Pop and Nouveau Realisme movements. Genevieve and Four Echoes retells the myth from her 1939 work in biomorphic abstraction, with curving, clover-shaped planes of color standing in for the fable’s titular character. Several galleries pay substantial attention to Oppenheim’s abstract paintings, collages, and sculptures, encouraging us to consider her non-figurative works with equal reverence as her well-known Surrealist assemblages. Oppenheim’s abstract works stun the viewer with their simple magnitude: she evokes natural shapes, pairs of lovers, or her own body with a language of forms that is both subtle and unambiguous. There She Flies, the Beloved (1975) is a painting depicting a hermaphroditic shape – both phallic and triangular – rocketing across the picture plane. Oppenheim believed in a “dual-sex spirit” present in herself, and that delineating a hard line between “male” and “female” forms or themes belittled the creative impulse that powered her work. Here, we might consider the spectacular power of deconstructing the gender binary in such an unambiguous, powerful visual language, playing on and breaking up “gendered” shapes with vivid turquoise paint, richly textured tortoiseshell, and molded plastic shapes.

The title of the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition originates from a series of drawings Oppenheim produced in the final years of her life (fig. 3). Titled My Exhibition, the artist designed her own retrospective with a suite of drawings chronologically organized that depict miniaturized and scaled colored sketches of 200 works. Placed as a mid-exhibition pause, MoMA presents the entire suite of drawings in their own gallery, so that the viewer might see how Oppenheim conceived of her own career as an elder artist. MoMA’s exhibition celebrates Oppenheim by prioritizing the artist’s vision of her own career, encouraging the viewer to reconsider how they have previously considered Oppenheim’s work and how they might expand their understanding of her. One might, as Oppenheim herself wanted, to centralize the spectacular, not just the surreal, in her work.

____________________

Katherine Gregory is an Art History PhD candidate at the University of Texas at Austin. A scholar of American art history, she is writing her dissertation on Robert S. Duncanson’s landscape paintings. She is the recipient of a 2022–2023 Luce/ ACLS Dissertation Fellowship.

____________________

Editors’ Introduction

by Sarah Horowitz

The term “spectacle” encompasses an array of meanings across disciplines. As early as the seventeenth century, “spectacle” was associated with the theatrical displays of early English drama. Furthermore, the rise of a new middle class particularly in France during the nineteenth century gave way to new interpretations of the expression.1 “Spectacle” in this historical context became linked to socio-economic ideas of capitalism. More recently, the word has taken on more abstract, conceptual definitions, particularly in scholarly understandings of postmodern society. For instance, cultural and political theorist Guy Debord’s idea of a “society of the spectacle” in the late 1960s offers a useful explanation and critique of capitalist culture, one in which excess imagery mediates human interpersonal relationships.2 “Spectacle” often connotes performativity in our contemporary world as the ubiquity of new media—film, multimedia installation, and other immersive spaces—transforms and sometimes disrupts our perceived realities.

Debord’s notion of “spectacle” is valuable for interpreting art and architecture. While his seminal text The Society of the Spectacle was published in 1967, Debord’s theories about consumerist tendencies can be applied to different situations across artistic media, time periods, and geographic boundaries. As an architectural historian, I want to call attention to how Debord’s philosophies of the spectacle aid in an understanding of postwar American architecture, specifically the example of performative spaces such as Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts in New York City. The building project was a collaborative effort in which American architect Wallace K. Harrison led a team of prominent modern designers in drawing up a plan for the premier performing arts complex in the United States. The centerpiece for the Lincoln Center campus is a large rectangular plaza—modeled after a Renaissance-era piazza—framed by the travertine-clad arcaded facades of the New York State Theater (now David H. Koch Theater), Metropolitan Opera House, and Philharmonic Hall (now David Geffen Hall) (fig. 1). As a public outdoor space, the plaza contrasts with the exclusive indoor environments of the surrounding performance venues where in order to enter, one must be a paying customer. These tensions of who is privy to these exterior and interior spaces at Lincoln Center evoke Debordian ideas of the spectator and passive consumer. According to Debord, the experience of these outside and inside realms at Lincoln Center would be solely mediated by capitalism and consumer relationships. We, as a result, become enveloped by this spectacle of confrontation with multiple sensory environments—architectural, performative, and visual. However, I would argue that people traversing the plaza or attending a performance at Lincoln Center assume more agency than Debord implies in their engagement with these spaces. By actively moving through and participating in the various landscapes and buildings making up Lincoln Center, people become a fundamental part of the spectacle.

In this issue of SEQUITUR, notions, expressions, and experiences of “spectacle” are thoughtfully considered by the selected contributors. In her feature essay “Paved Paradise: The Concrete and the Stuplime at Parc des Butte-Chaumont,” Madeline Porsella explores tensions between nature and culture in the use of concrete to create the Parc des Butte-Chaumont, a man-made landscaped park that opened in Paris in conjunction with the Exposition Universelle of 1867. Porsella draws a striking comparison between the park’s spectacular display of new materials and technology in the late nineteenth century with the detrimental impacts of concrete on the present-day Anthropocene.

Rowan Murry also discusses spectacle in the context of the built environment and historic preservation. Focusing on the archeological site of Pompeii as an example of what she defines as “tourist folklore,” Murray examines how this ancient ruined city—one of the most visited UNESCO world heritage sites—is remarkable for its associations with magic and a fabled curse where visitors stealing material objects from the site bear the consequences of their actions. The essay presents an intriguing interpretation of Pompeii as a place haunted by this “dark tourism” where historic preservationists must balance their responsibility as custodians of a historic site with the lucrative possibilities of promoting ahistoric and potentially harmful tourist folklore.

The third feature essay in this issue conjures up one of the major debates concerning the spectacle and its definition and representation in art, architecture, and other forms of visual culture: where do the boundaries of the spectacle lie? In “Ruining the Spectacle: Nikita Gale’s END OF SUBJECT,” Darcy Olmstead probes the possible limits of the spectacle embodied in the work of contemporary installation artist Nikita Gale. Referencing the past theories of the spectacle and visuality put forth by Debord and art historian Jonathan Crary, Olmstead argues that Gale’s multimedia work offers a disjointed view of the spectacle where viewers are constantly pulled in competing directions by different visual and auditory elements. The spectacle in this case implodes.

These fluid parameters of what defines—or even obliterates—the spectacle are further questioned in this issue’s research spotlights and exhibition reviews. Levi Sherman investigates how the concept of institutional critique can be applied not only to museums and archives, but also libraries. Sherman asks readers to reconceive the public institution of the library as a space where artists can intervene to reveal power dynamics between these institutions and the patrons they serve. In contrast, ambiguous relationships between performance artists and (paying) spectators at the Chale Wote Street Art Festival in Ga Mashie, Accra, explored by Colleen Foran, expose the haziness of the spectacle and its precise definition.

In some instances, the spectacle transforms into the uncanny. Exhibitions such as The Amant Foundation’s SIREN (some poetics), reviewed by Farren Fei Yuan, problematize the viewer’s engagement with and experience of the everyday as it is visually expressed in contemporary art installations inside and outside the gallery spaces. Like Olmstead and many of the other authors included in this issue, Yuan suggests that there is an inevitable dissolution of the spectacle that takes place in the tug of war between perception and so-called reality. Spectacle and its connection to the uncanny are clearly discerned in Katherine Gregory’s critique of Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition, on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gregory contends that by representing the breadth of Oppenheim’s work beyond the artist’s most famous surrealist sculptures, the exhibition sheds light on other aspects of Oppenheim’s artistic career, including the spectacular. For example, the artist’s dissolve of gender binaries in her work, Gregory suggests, becomes a means by which Oppenheim engages with spectacle.

While it may be a futile effort to pinpoint the boundaries of the spectacle, the authors in this fall’s issue of SEQUITUR uncover the possibilities of the term for articulating intangible bonds and disjunctures between spectators and the visual and built environment. Systems of control and power may exist in the capitalist society portrayed by Debord, but we have the authority to shape the spectacular into something of our own making.

____________________