White Shadows: Anneliese Hager and the Camera-less Photograph

Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA

March 4–July 31, 2022

by Renée Brown

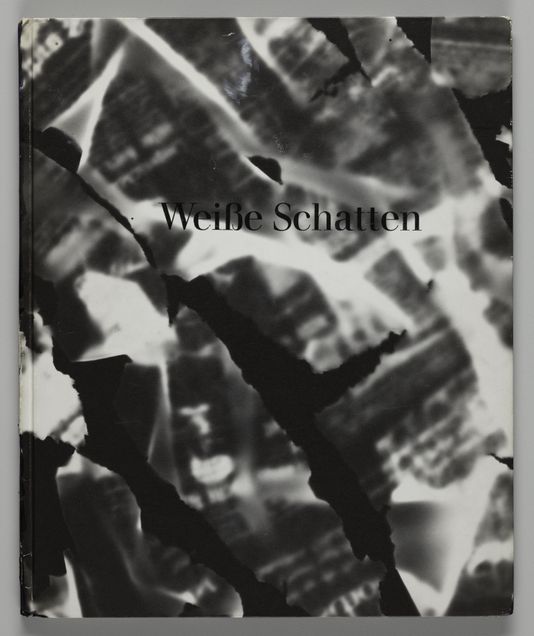

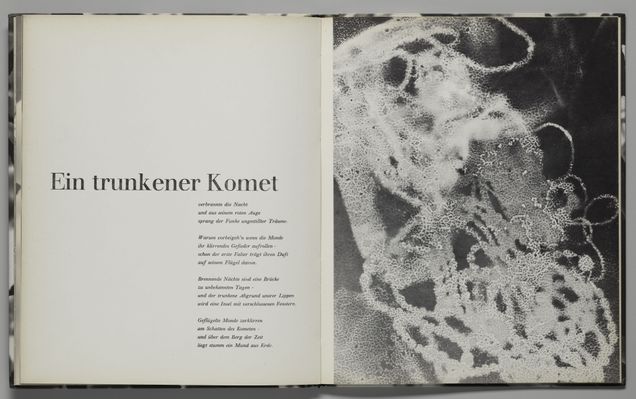

In 1964 German artist Anneliese Hager (1904–1997) published a book of her poems and photograms entitled Weiße Schatten (White Shadows). Released in an edition of fifty-five, each volume has a unique cover featuring a full-bleed photogram by Hager (fig. 1). The layered black and white images both invite and frustrate the urge to decipher; blurred lines of typed and handwritten text hover at the limits of legibility while geometric patterns suggest textile and organic forms but refuse categorization as one or the other. The book’s contents are no less enigmatic. Reproductions of abstract photograms suggesting vapor, cosmic dust, riverbeds, rumpled bed sheets, and skin cells juxtapose German poems bearing titles like “Zwischen Zeit und Stunde” (Between Time and Hour), “Halluzination” (Hallucination), “Nebel” (Fog), “Ein Trunkener Komet” (A Drunken Comet), and “Sirenengesang” (Siren Song). Text and image neither explicate nor illustrate each other but engage in an oblique dialogue. For instance, the photogram accompanying “A Drunken Comet” shows a tangle of beaded lines evoking the erratic trajectory of the poem’s inebriated subject (fig. 2). The text riffs on the whimsical dream-imagery of the photogram, connecting the celestial and terrestrial, the remote and mundane.

These themes in White Shadows run throughout Hager’s work as a whole. Indeed, the book may be read as a kind of culmination, marking the end of her four-decade exploration of camera-less photography. The title references Hager’s name for the complex monoprints she made by directly placing objects on light-sensitive paper. When exposed to light, the areas of paper obscured by objects remain white, while the negative spaces darken. Hager’s titular phrase highlights the inverted shadow-effect of this process and hints at a deeper interest in the medium’s capacity to confound natural order and codified systems of meaning.

Hager’s phrase figures in the title of the Harvard Art Museums’ ongoing exhibition White Shadows: Anneliese Hager and the Camera-less Photograph curated by Dr. Lynette Roth, Daimler Curator of the Busch-Reisinger Museum at the Harvard Art Museums. The show is among the first to focus on Hager’s photograms, which have been largely left out of the historical record due to the loss of her early work in the 1945 Dresden bombing and her later eclipse by male contemporaries. In addition to a copy of White Shadows, the exhibition displays twenty-nine of Hager’s photograms dating from the 1940s–1960s. These works appear alongside other photograms by nineteenth and twentieth-century scientists and artists, positioning Hager as a key figure in the medium’s history.

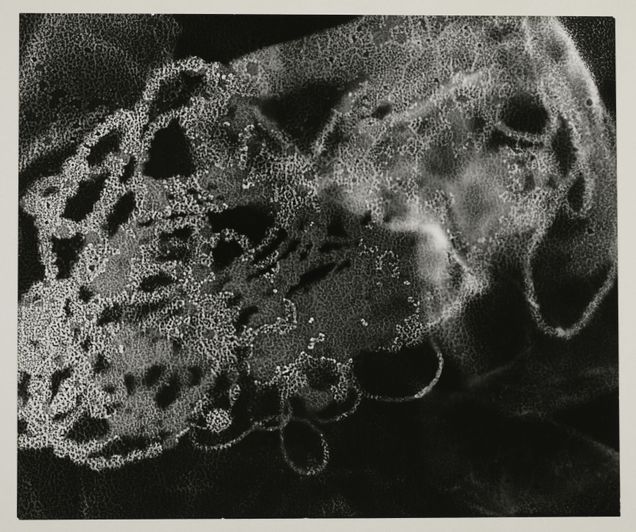

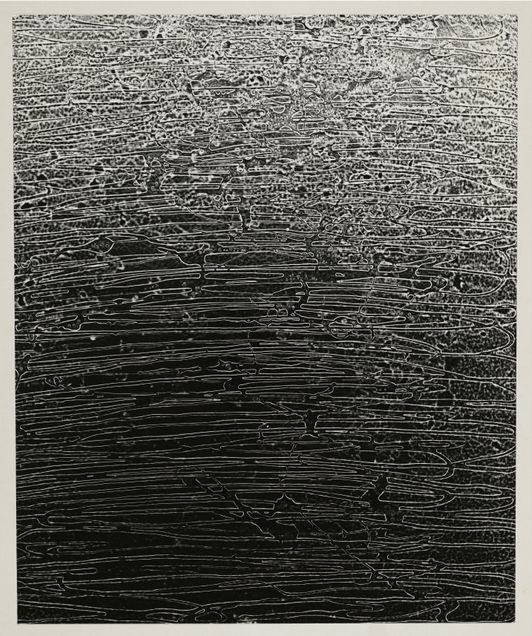

The exhibition also features the work of avant-garde artists such as László Moholy-Nagy and Man Ray, who popularized the use of photograms in the 1920s. While Hager did not know the two personally, she encountered their work through publications such as Moholy-Nagy’s landmark book Painting, Photography, Film (1925) and articles on photograms in the popular women’s magazine Uhu. Although inspired by these artists, Hager’s photograms look very different. Moholy-Nagy and Man Ray both produced images with strong figure-ground relationships and centralized compositions, as opposed to Hager’s dense, overlapped patterns and compositions that extend to the edges of the picture plane, making it hard to distinguish top from bottom. For example, Endless Chain II is displayed in the gallery with a horizontal orientation while it is reproduced vertically in White Shadows (fig. 3). Other instances of this all-over style include Compacted Structure, which presents a stack of frenetically oscillating lines (fig. 4, 1962).

The intricate yet expansive structures of Hager’s photograms signal another source of inspiration besides the avant-garde. Between 1922 and 1924, Hager worked as a technical assistant in the science of wool manufacturing. These years spent examining the thatched fibers of wool through a microscope provided Hager a visual vocabulary full of tactile nuance, sensitive to qualities of translucency and opacity.

Picking up on this scientific dimension of Hager’s work, the Harvard exhibition connects her to nineteenth-century pioneers of camera-less photography, including British botanists Anna Atkins and Ella Hurd, whose work is also on view. These early photographers created cyanotype photograms by placing plant specimens on paper coated with a photosensitive chemical mixture known for its blue color. The stunning silhouette images of ferns, seaweed, and other flora functioned primarily as scientific documents. Although Hager was not aware of these predecessors and did not use the cyanotype printing process, the comparison serves to foreground Hager’s scientific background and situate her in a lineage of women who created innovative photograms at the fringes of scientific and artistic developments.

This contextualization frames another ambition of the exhibition: to construct a history of the photogram emphasizing women’s contributions. This is an exciting revision, yet it competes somewhat with the show’s primary focus on Hager’s work. As a result, certain facets of her practice are underplayed, such as the relation between her poetry and photograms. Though White Shadows: Anneliese Hager and the Camera-less Photograph presents Hager still somewhat in the shadows of canonical “masters” of the photogram, her work emerges as something unique, that speaks as much to Hager’s unique vision as to the history she represents.

____________________

Renée Brown is a PhD student at Boston University where she studies twentieth-century American visual and material culture with a focus on the history of photography. Her work on these topics engages questions of epistemology and representation, considering the different forms of knowledge shaped through text and image.