news

Editors’ Introduction

reproduction with pencil and white gouache, 11 3/4 x 7 7/8 in.

Welcome to “LOL,” SEQUITUR’s current issue, which takes as its theme humor, play, and amusement of all kinds. In many ways creativity lies at the core of laughter and fun, and the scholarship presented here highlights how art and visual culture reflect and engage with humor, absurdity, and parody. Our contributors examine a range of material and approach the theme from various angles: they consider funny and amusing internet content both as source material for their own work and in relation to art history and online culture; they explore the ways in which artists deploy notions of play and humor in order to mount social critiques; and they meditate on the place of humor in the content and conception of current exhibitions. Ultimately, the scholarship and art assembled here highlight the close relationship between the realms of the creative and the comedic.

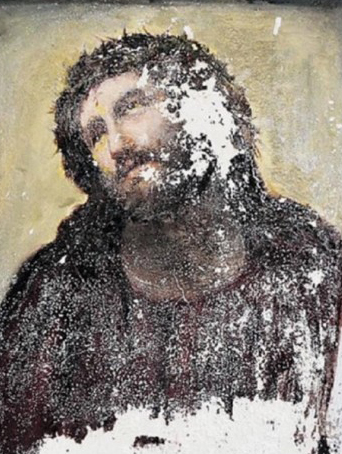

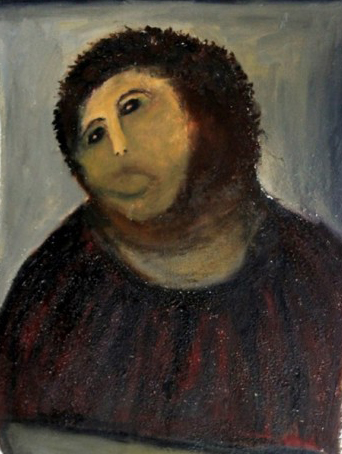

The featured essays in this issue of SEQUITUR explore the role of humor in two distinct ways. In her essay, “Grotesque Irreverence: The Transformation of Ecce Homo,” Sophie Handler reflects on the phenomenon of Cecilia Giménez’s hilariously unfortunate restoration of a Spanish fresco depicting Christ in 2012. Handler follows the instant internet sensation ignited by this accidental disfigurement and the manifold Ecce Homo memes that pay tribute to it. Ultimately the simultaneous surprise, humor, and horror that Giménez’s intervention has elicited place the work within the paradigm of the grotesque, and the new appreciation it has gained as an expressive evocation of personal devotion brings new meaning to the idea of laughing at God. An artist’s intentional use of humor is examined in Janna Schoenberger’s essay “Jean Tinguely’s Cyclograveur: The Ludic Anti-Machine of Bewogen Beweging.” Shifting gears to postwar Europe, Schoenberger explores the context of a 1961 kinetic art exhibition held in Amsterdam. One of Tinguely’s pieces featured in the show was a bicycle-inspired sculpture that could be activated when a viewer sat in its “saddle” and began pedaling. Through a careful consideration of Tingueley’s Cyclograveur and a close look at the modern transformations of postwar Europe, Schoenberger argues that the artist marshaled humor and absurdity to mount a critique of the increased mechanization of Dutch society.

The four exhibition reviews within this issue examine, respectively, an ongoing installation in Washington, D.C., a recently closed show in Los Angeles, and two current exhibitions in London and Cambridge, MA. Hyunjin Cho reviews the Peacock Room REMIX at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, DC. This exhibition revolves around Darren Waterston’s Filthy Lucre installation which is inspired by James McNeil Whistler’s famous Peacock Room interior. Cho elaborates on the ways in which Waterston’s piece may be considered a parody of the original and gives readers a close account of the multifaceted concerns and subjects explored by the show. Shannon M. Lieberman’s review of The Younger Generation: Contemporary Japanese Photography at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles keenly highlights elements of play and humor embedded in the works featured in this show. At the same time, Lieberman considers the exhibition’s aim to challenge the label “girl photography”—applied to young female Japanese photographers—and gives readers a thoughtful account of how this dated and sexist term could be further invalidated. The motif of play is explored further by SEQUITUR Junior Editor Erin McKellar in her review of Alice in Wonderland, an exhibition at the British Library in London, held in honor of the sesquicentennial of the publication of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. As McKellar illustrates, the show, which features seminal manuscripts and memorabilia related to Alice, effectively evokes the childlike playfulness of the original text in its interactive design and unexpected arrangement. At the Harvard Art Museums, Joseph Saravo explores the wonder-filled world of Hieronymus Bosch in Beyond Bosch: The Afterlife of a Renaissance Master in Print. This intimate exhibition focuses on the entrepreneurial artists and printers who capitalized on the supernatural style of the master following his death, and Saravo reveals how this grouping of grotesquely humorous images, mostly from a private collection, tells an important story of the Bosch brand.

Catherine O’Reilly, coordinator of the 2016 Boston University Graduate Student Symposium in the History of Art & Architecture, reflects on this year’s conference, which took place on February 26th and 27th at the Boston University Art Gallery and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Entitled “Serious Fun: Expressions of Play in the History of Art and Architecture,” the symposium corresponds to the theme of this issue, and O’Reilly provides insights into the serious relationship of power, play, and propaganda as well as the light-hearted role of play and fun in identity construction and communal involvement. She also summarizes the keynote lecture given by Dr. Paul Barolsky, who challenged art historians to reject somber evaluations of artworks that epitomize joy, jest, and jocularity.

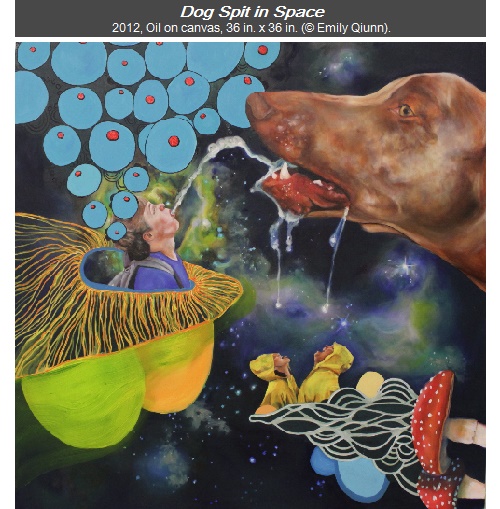

Finally, this issue of SEQUITUR features two visual essays by MFA students at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign and the University of Colorado, Boulder. Nicole Brunel’s visual essay, “badthingshappen…” documents her web project which appropriates videos and photos found on slapstick Instagram accounts. As Brunel edits, she removes the humorous contexts and fuses this material into a single narrative. What remains are only fragments of the tragic failures that so often define viral internet humor. Emily Quinn’s visual essay features four paintings in which she uses unsettlingly funny and absurd imagery to examine stereotypical masculinity. The artist draws on her experiences and family history to construct narratives that combine comedy, fantasy and a critical look at various clichéd activities and preoccupations.

Our authors approach the theme of “LOL” from diverse vantage points, and we are delighted that they engage various manifestations of humor in art with such innovative scholarship. As we finish our second and final year on the SEQUITUR editorial board, we would like to extend our warmest thanks to our readers, contributors, supporters, and collaborators. Without all of you this journal would not have grown so quickly and expanded so fruitfully. Working on the SEQUITUR team—first with Beth, Martina, and Naomi, and now with Erin, Jordan, and Sasha—has been a great pleasure. We are grateful for the experience and look forward to watching the exciting work ahead as SEQUITUR enters its third year. For now, we hope that you can find something that makes you laugh out loud within this issue, whether you LOYO or ROFL with friends.

Ewa Matyczyk & Steve Burges

Emily Quinn

My work examines stereotypical masculinity using humor, mystery, and absurdity to critique male preoccupation with sex, objectification of women, and exhibitionism. The painting, Dog Spit in Space, uses symbolism and the language of Photoshop to refer to ejaculation, while Man Camp is a folkloric representation of men policing each other’s masculinity. Working loosely from my experiences, memories, and family history, I create narratives that exist in the nexus between fantasy and reality.

I grew up in Alabama, where the tradition of storytelling is alive and well in the daily rehashing of life’s tragedy and comedy. Just as a story is exaggerated over time, my work becomes less biographical with each edit. Beginning with family photographs and stories, I edit them until the original content is transformed. Through this process, I am able to emphasize what is often left unsaid and reclaim ownership over my fears and identity as a Southern woman.

Emily Quinn

The Younger Generation: Contemporary Japanese Photography

The Younger Generation: Contemporary Japanese Photography

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA

October 26, 2015 - February 21, 2016

In the 1990s, critic Iizawa Kōtarō coined the phrase “girl photography” to refer to the work of young Japanese photographers who happened to be women. The Younger Generation: Contemporary Japanese Photography, on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum, in Los Angeles from October 26, 2015 - February 21, 2016 is curator Amanda Maddox’s challenge to this sexist, homogenizing label. The exhibition presents the work of five women photographers – Kawauchi Rinko, Onodera Yuki, Otsuka Chino, Sawada Tomoko, and Shiga Lieko – demonstrating how the diversity and range in their work counters “the idea that ‘girl photography’ could define a generation of practitioners.”[1] Despite Maddox’s stated aims and the strength of the work in the exhibition, the show lacks sufficient context to truly explain and then dispel the concept of “girl photography.” Further, it does not embed “girl photography” within a larger history of Japanese photography or of sexism in contemporary art. In short, it fails to establish why the problematic label “girl photography” must be addressed rather than dismissed or ignored. More

Alice in Wonderland

Alice in Wonderland

British Library, London

November 20, 2015 – April 17, 2016

The British Library has staged a free exhibition to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the publication of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), the now well-known story of Alice’s descent through a rabbit hole into a fantasy world inhabited by anthropomorphic creatures. The display engages the story of the book from its initial telling to Alice Liddell and her sisters through its publication, with iconic illustrations by John Tenniel, to the present. Because the story explores the theme of childhood imagination, the exhibition’s material is inherently fun and often vibrant. Among the first objects that the viewer encounters is Carroll’s original handwritten and illustrated manuscript, Alice’s Adventures Under Ground (1864), part of the British Library’s expansive collections. Various editions of the book, including one by surrealist artist Salvador Dalí, appear throughout the display. These versions, coupled with large-scale illustrations, film clips, Alice-related objects and ephemera, illuminate the ways in which the story has been continually reimagined in the 150 years since its first publication.

Jean Tinguely’s Cyclograveur: The Ludic Anti-Machine of Bewogen Beweging

Bewogen Beweging (Moved Movement) was an exhibition held at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, from March 10 to April 17, 1961. Curated by two museum directors—the Stedelijk’s Willem Sandberg and Pontus Hultén, from the Moderna Museet, Stockholm—together with artists Daniel Spoerri and Jean Tinguely (1925–1991),[1] the show constituted a survey of Kinetic art as it presented nearly two hundred works by over seventy artists, all of whom contributed to the novel spectacle of rusty wheels, chains, broken typewriters, strollers, and alarm clocks that moved and made noises. Many of the works on display incorporated bicycles in various forms.[2] A Netherlandish metaphor for both play and utility, the bicycle is at once a child’s toy and the predominant mode of transportation for adults in Amsterdam. Examining in particular Tinguely’s Cyclograveur—a sculpture based primarily on the bicycle—this essay reveals that the exhibition deployed the illogical movements of mechanical components in a ludic critique of the rapid industrialization and modernization of the Netherlands after World War II.

2016 Symposium Reflection

Serious Fun: Expressions of Play in the History of Art and Architecture – The 32nd Annual Boston University Graduate Student Symposium in the History of Art & Architecture, February 26th & 27th, 2016

This two-day event was generously sponsored by The Boston University Center for the Humanities; the Boston University Department of History of Art & Architecture; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Boston University Graduate Student History of Art & Architecture Association; and the Boston University Art Gallery at the Stone Gallery.

Grotesque Irreverence: The Transformation of ‘Ecce Homo’

To expand the photos of before and after Cecilia Giménez's intervention, slide the toggle in the center.

The global online community erupted on August 21, 2012 following reports by the Spanish newspaper Heraldo of the failed attempt made by Cecilia Giménez, an elderly local amateur artist, to restore Elías García Martínez’s fresco Ecce Homo (Behold the Man) (Figure 1).[1] A gift from Martínez, the artwork was painted directly onto the wall of the Santuario de Misericordia church in the Spanish town of Borja in around 1930, and until 2012 had existed in relative obscurity. The work is unimposing in size, measuring just twenty inches in height and sixteen inches in width, and was originally painted by Martínez in a style strikingly similar to that of the high-Baroque works of Italian artist Guido Reni (1575-1642). Whilst general opinion amongst the press treated the fresco as “a work of little artistic importance,” because “Martínez is not a great artist and his painting Ecce Homo is not a ‘masterpiece,’” the fresco nevertheless held some sentimental value within the local community; residents’ attachment to it stemmed from an interest in historical preservation and general artistic authenticity as much as the inherent sanctity associated with the artwork.[2] The original image, which depicted Jesus crowned with thorns and gazing skyward in a traditional Catholic pose, had suffered significant moisture damage over the decades. Sources vary as to whether Giménez acted with or without permission from the priest, but local city councilor of arts and culture, Juan Maria Ojeda, was quick to defend the octogenarian parishioner, dismissing theories of malicious vandalism, and instead insisting that she acted with “good intentions,” despite having no formal artistic training.[3]

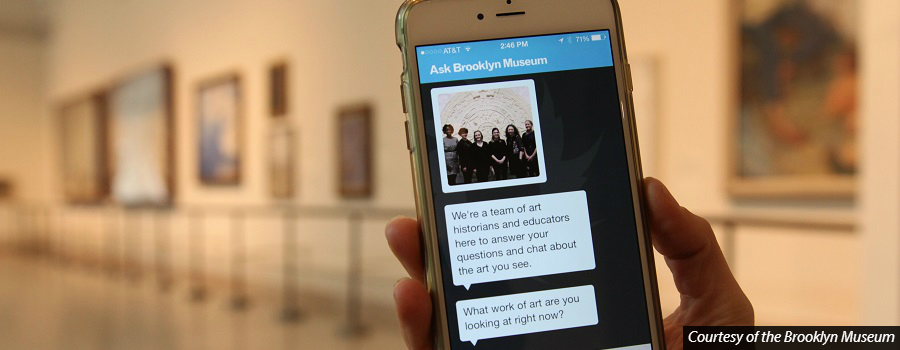

Engaging with Visitors, When Visitors Have Superpowers: Testing the ‘ASK Brooklyn Museum’ App

More empowered than ever, visitors to art museums typically enter these institutions equipped with digital tools that can mediate their experience of the objects within. [1] With an interest in how technology like smartphones could impact curatorship, I accepted a position as a visitor liaison during the summer of 2015 at the Brooklyn Museum. Officials there were reimagining the entire visitor experience preceding Anne Pasternak’s assumption of the museum directorship in September 2015. In June 2015 the museum unveiled an original smartphone app called ASK Brooklyn Museum, which makes it possible to chat with museum experts at any point during a visit without delay. [2] It was my role to encourage museum-goers to put this tool to use.

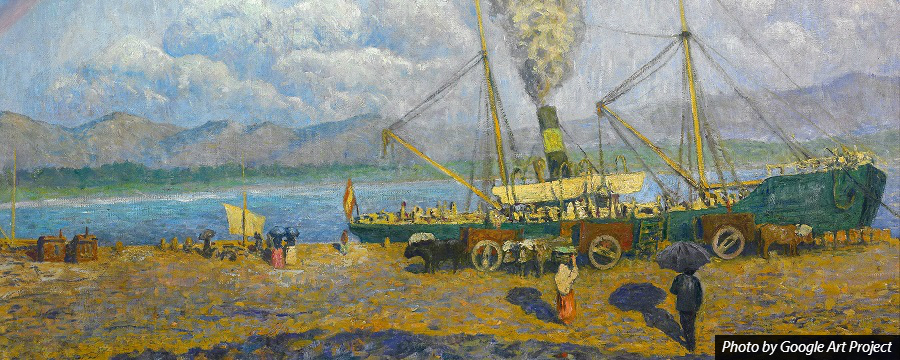

“So-Called Synonyms:” Translating Darío de Regoyos’s ‘España negra’

I first became familiar with the paintings of Spanish artist Darío de Regoyos (1857-1913) at a survey exhibition held at the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, in Madrid, on the centenary of his death. Captivated by the sun-dappled fields and villages of Regoyos’s Spanish landscapes, I also began reading his 1899 travelogue, España negra. Immersing myself in the words of an artist whose brushwork I was simultaneously getting to know led me to translate the text, as yet unavailable to English readers. As I would soon discover, both translation and art history are fundamentally acts of interface—the former, the transposition of writing in one language into another language, and the latter, the evocation of objects with words.

‘Camera Ottomana: Photography and Modernity in the Ottoman Empire, 1840-1914’

Camera Ottomana: Photography and Modernity in the Ottoman Empire, 1840-1914

Koç University Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations, Istanbul, Turkey

April 21 – August 19, 2015

Camera Ottomana, curated by Zeynep Çelik, Edhem Eldem, and Bahattin Öztuncay, on display during the summer of 2015 at Koç University’s Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations (RCAC) on Istanbul’s bustling pedestrian Istiklal Street, ambitiously took on the complex role of photography in the last years of the Ottoman Empire. The exhibition used one interface to explain another: a variety of tools—digital, cartographic, and written—were employed to help the visitor understand how an empire’s elites represented their dominion through photography. Freestanding light boxes and digital close-ups were just a few of the ways in which the exhibition exposed visitors to photographs in various forms, including studio portraits, post cards, newspapers, film footage, and albums. Through maps, timelines, and explanations of different image technologies in Turkish and English, the visitor could take-in ample artistic information without being overwhelmed. Supplementary explanatory and political text, which seemed lacking in the exhibition, is provided by the accompanying book of four essays on Ottoman photographic history, three of which were written by the curators.