news

Excess—The 34th Annual Boston University Graduate Student Symposium in the History of Art & Architecture

Excess – The 34thAnnual Boston University Graduate Student Symposium in the History of Art & Architecture, March 2–3, 2018.

This two-day event was generously sponsored by the Boston University Center for the Humanities; the Boston University Department of History of Art & Architecture; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and the Boston University Art Gallery at the Stone Gallery.

What does it mean to be excessive? The 34thannual Boston University Graduate Student Symposium in the History of Art and Architecture called on graduate students to address art historical topics related to this very question. The theme of “Excess” inspired six presenters and our keynote speaker to explore the historically constructed idea of the extraneous, the leftover, or the superfluous, even that which is deemed peripheral or abject. The symposium began on March 2nd at the Boston University Art Gallery at the Stone Gallery with a keynote address by Dr. Cary Levine, Associate Professor of Contemporary Art at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Kicking off the opening evening of the symposium with zeal, Professor Levine took the audience on a discomfiting visual adventure into the unrestrained overconsumption of Paul McCarthy’s work. Examining what he calls the artist’s “food flinging frenzies,” Levine spoke to the deliberate excess that is McCarthy’s practice. The artist uses food and the politics of food to question the western construct of self-restraint by revealing the tension between individual moderation and overconsumption. Levine concluded by stressing that McCarthy’s performative works manifest in the impulsive, going so far as the perverse, to demonstrate imprisoned human vulgarity. This complicated overindulgence problematizes the vulnerability of our norms and forces us to ask what is normal, what is natural, and what is too much. Unsurprisingly, a lively question and answer session followed Professor Levine’s talk, inspiring both students and faculty to seek additional insights into the artist’s process, his audience, and his greater reception.

Professor Levine provided a fitting introduction to a stimulating symposium that featured six graduate student paper presentations at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston on Saturday, March 3rd. Sasha Goldman, my co-coordinator, and I worked with discussants Alex Yen and Alison Terndrup to organize two sessions around themes of Excess. The morning session, entitled “Moreoverdone,” featured three papers that emphasized a careful scrutiny in assessing overindulgence and luxury. In her paper, Luxuria in the Shadow of Vesuvius: Personal Decoration as a Means of Constructing Feminine Personae at Oplontis, Kearstin Jacobson (Montana State University) started off our morning session by examining extravagant Roman jewelry from Campania and the difficult task of unpacking meaning through various moral and historical lenses. Caroline Murphy (MIT) introduced us to the seventeenth-century need to explain and legitimize seemingly extraneous pagan imagery as Christian iconography in her paper, Taming Excess: Antonio Bosio’s Roma Sotterranea(1632) and the Problematic Evidence of Catacomb Paintings in Counter-Reformation Rome. The paper examined the first historical publication that documented Christian paintings in the Roman catacombs and revealed the convoluted lengths to which the author ventured to fit these images into the strict tenets of the Counter-Reformation. Anna Ficek (CUNY) closed the morning session with her paper, Artifice and Excess in Urban Images: Picturing the Decline of Potosi in the Eighteenth Century.Through an examination of extraordinarily detailed paintings, this paper revealed the problematic omission of adversity suffered by the local population in eighteenth-century Potosi in favor of crafting a history of pomp and excess in line with the elite’s political agenda.

After a break for lunch, the symposium continued with an afternoon session entitled “More-nament” which focused on themes of excess related to group identity and the idea of overindulgence in relation to the quotidian. In her paper, Gilding the Grave: The Lavish Aesthetics of Death in a Picturesque Cemetery, Noël Albertsen (University of California, Davis) explored the extravagant aesthetics of Victorian monuments in a picturesque cemetery in Sacramento, California. The sublime quality of this resting place, inspired by nineteenth-century Parisian cemeteries, resulted in a romantic urban atmosphere of heightened emotion and deep mourning. Amanda Lett (Boston University) led us through the intricacies of nineteenth-century American bank note imagery in her paper, Too Handsome for Use: Bank Note Vignettes in the Antebellum Era. Reliant on imagery engraved on paper money as a way to convey trust, banks saturated their notes with agrarian and allegorical figures that became so overdone and overproduced that they essentially lost their meaning. Finishing out the afternoon session was Ashley Duffey (Pennsylvania State University) and her paper on a series of photographs by Robert Rauschenberg entitled, Glut on the Market: Robert Rauschenberg’s ‘Rome Flea Market’ and Post-War Italy. By focusing on Rauschenberg’s experience in Italy during the post-war period, this paper argued that the artist perceived the flea market photographs he took as capturing the extraordinary, resulting in an intentional blurring between simple tourist pictures and a complex American-Italian consumer relationship under the Marshall Plan.

The keynote lecture and all six graduate papers demonstrated how the theme of excess is a construct begging to be upended and reexamined. From overindulgence and luxury, to the abject and perverse, the art history of excess proves Oscar Wilde may have been right when he said, “moderation is a fatal thing. Nothing succeeds like excess.”

Jennifer Tafe

Zapatista Embroidery as Speech Act in Zapantera Negra

On January 1, 1994, the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (EZLN or Zapatista Army of National Liberation) declared war on the Mexican government. Indigenous fighters engaged in a guerrilla attack and seized nearby cities, towns, and ranches and occupied the colonial capital of Chiapas, San Cristóbal de las Casas. Though an eventual ceasefire was called, Zapatistas still maintain communities throughout Chiapas today, where they function autonomously without Mexican government assistance or leadership. [1] Zapatistas are a left-wing revolutionary political and militant group made up of mostly rural indigenous people from the Lacandon Jungle in Chiapas, Mexico. [2] They are opposed to neoliberalism and economic globalization, which they perceive as threats to indigenous communities that have been dispossessed over a 500-year period of colonial and imperialist struggles. They demand “work, land, housing, food, health care, education, independence, freedom, democracy, justice and peace” for all. [3] To these ends, the Zapatista movement calls for the re-conceptualizing of political institutions and world systems.

notes about contributors

Bailey Benson is a doctoral student at Boston University, where she studies the art and architecture of ancient Rome. Her research interests include the role of women in ancient Greece and Rome, the articulation of identity and memory in the ancient world, and the archaeology of the Roman East.

Daniel Healey is a PhD candidate in the Department of Art and Archaeology at Princeton University. His dissertation is on stylistic retrospection in Roman art and visual culture.

Cortney Anderson Kramer is a second year Art History and Material Culture PhD student at the University of Wisconsin – Madison, where she studies vernacular art-environments.

Christopher Lacroix is a second year MFA student at the University of British Columbia, and has a BFA from Ryerson University. His research and practice investigates queer and gay subject formation and the ways in which these subjectivities are performed. Lacroix is a recipient of the Joseph-Armand Bombardier Scholarship awarded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Jeff Paul is a graduate student in the Department of Art History at Columbia University. His research focuses on contemporary art and visual culture with an emphasis on mass media, linguistics, and digital technology. He works at David Zwirner and Artsy, and previously held positions at Artnet, the MIT List Visual Arts Center, and Adobe.

Jessica Rosenthal is a second year MA student at Williams College, where she studies nineteenth and twentieth-century art, focusing on works on paper. Her interdisciplinary research looks at discourses from art therapy as a way to challenge tropes of art associated with mental illness. She is also the Education Intern at the Clark Art Institute.

Madison Treece is a PhD student in Visual Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her work focuses on contemporary Chicanx, Latinx, and Latin American visual culture with an emphasis on politics, borderlands, and the colonial body.

Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity

Leighton House Museum, Kensington, London

July 7 - October 29, 2017

At Home in Antiquity presents works by one of Victorian Britain’s most acclaimed classicizing painters, the Dutch-born Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912), in the home and studio of another—his friend and colleague Frederic, Lord Leighton (1830-1896). As a painter of antiquity, Tadema distinguished himself by depictions of the quiet, quotidian aspects of ancient life. His subjects feast, pine, and loll in meticulously researched domestic interiors or atop breathtaking Mediterranean promontories. The Leighton House is well suited to the show’s domestic emphasis, which argues that “home” was just as integral to Tadema’s working methods as it was to his painted subjects. Tadema, like Leighton, painted from purpose-built London studio-houses, which brought the lives of his whole family into intimate and fertile contact with his work. The exhibition rehabilitates his “Victorians in togas,” revealing them as the compelling personages of his wife Laura, also a painter, and his daughters, whose own artistic endeavors were nurtured by a lively familial enterprise of art-making.[1] Displaying many of Tadema’s greatest works, the show also provides views of his homes, pieces of his furniture, and paintings made by his family and friends.

Editors’ Introduction

In SEQUITUR’s open issue, the articles embody an eclecticism in method and content, highlighting diverse material that, when placed together, speak to one another and facilitate a rich and productive dialogue. By assembling a varied selection of contributions, the open issue presents a broad spectrum of graduate scholarship that draws connections and sparks conversation.

Leisure and Luxury in the Age of Nero: The Villas of Oplontis Near Pompeii

Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, MA

February 3 – August 13, 2017

The Smith College Museum of Art serves as the third and final venue for the exhibition Leisure and Luxury in the Age of Nero: The Villas of Oplontis Near Pompeii.[1] Housed in a single, large gallery on the museum’s ground floor, the exhibition hosts a rich collection of over two hundred objects, many of which have never been displayed outside of Italy. The display effectively exhibits the opulent lifestyle of the wealthiest Roman citizens through a collection of rich jewelry, sumptuous marble sculptures, and reconstructions of lavish domestic wall painting.

La Marchande d’Amour : The Commodification of Flesh and Paint

Niçois watercolorist and oil painter, Gustav Adolf Mossa (1883-1971) exaggerated and satirized popular nineteenth-century motifs by coating his compositions with caricature. In turn, his oeuvre is slippery, referencing multiple—even conflicting—styles and tropes especially evident in the watercolor La Marchande d’Amour (1904) (Figure 1). Mossa crowds La Marchande d’Amour with references ranging from classical subjects to stereotypical modern masculine types with a critical and comical wit. His multilayered pastiche satirizes artistic production, comparing it to the commodification of flesh enacted by a Venus-like merchant who butchers and sells female cupids to a sea of waiting male customers. By comparative analysis, I will argue that Mossa’s complex layering of recognizable artistic motifs, including classical iconography and modern types, supports a self-reflexive interpretation of the production and commodification of art as akin to prostitution.

Am I doing this right?

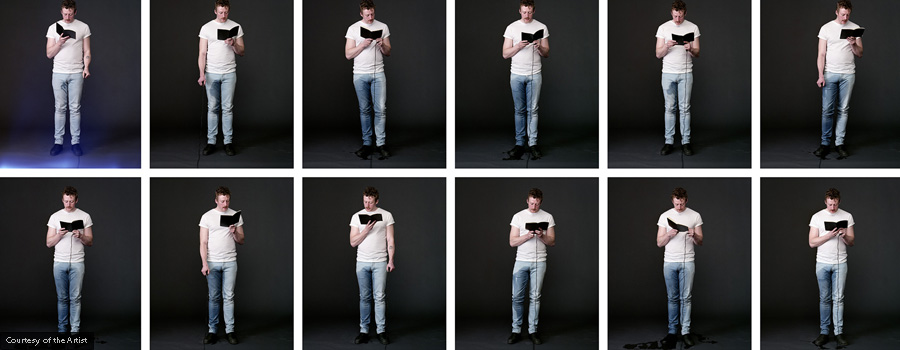

Am I doing this right? (2017) is the result of a near six-hour performance in which I read a year’s worth of journal entries phonetically backwards in a pitiful and misguided attempt to review myself and achieve self-actualization. As my voice grew coarse, I drank water and as I drank water I needed to pee. Dedicated as I was to this fruitless attempt at self-reflection, I stubbornly continued to read my journal, wetting my pants rather than take a break. With a shutter release in hand, I photographed myself each time I released urine, choosing to capture moments of paradox in which my body is in an abject and vulnerable state, yet stable and in control.

The Face of Battle: Americans at War, 9/11 to Now

The National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

April 7, 2017 – January 28, 2018

In the National Portrait Gallery’s ongoing exhibition, The Face of Battle: Americans at War, 9/11 to Now, the first face that you see is your own. Your likeness, dark and indistinct, is reflected through a red and black American flag, hung vertically. The image is displayed on the glass surface of twin pillars that mark both ends of the exhibition’s hallway (Figure 1). The symmetrical layout of the space echoes this mirroring effect: three doorways parallel one another, each threshold marked with the name of the contributing artist whose work the room contains.

EXO EMO

Greene Naftali, New York

June 29 – August 11, 2017

EXO EMO, curated by Antoine Catala and Vera Alemani, gathers thirty-one works by over nineteen artists and collectives, occupying three divided spaces at Greene Naftali as well as the hallway, front office, and even restroom of the gallery. The exhibition’s ambiguous title and the absence of any wall text leaves the viewer with only a cryptic press release for textual guidance. The document is made up of a series of solicitations by the curators for a short sentence or two from each artist about their respective emotional relationship to their work. Collectively, these statements allude to the show’s organizing themes of consumerism, consumption, and commodification. The exhibition itself presents an ambitious, though somewhat disjointed, array of works that “vacillate between horror and humor,” as one contributor attests.[1]