news

Between Spaces: The Domus Aurea, the Vatican Loggetta, and Foucault’s Heterotopia

by Tyler Rockey

The Renaissance artists and antiquarians who descended into the earth and into the ruins of the Domus Aurea, the palace of the first-century Roman emperor Nero, found themselves in a strange space where their present was collapsed with the ancient Roman past and surrounding them was fantastical and bizarre painted decoration. This rediscovery in the late 1400s of an ancient Roman structure, with extant examples of grotesque painting, expanded and spurred interest in this style and technique of decoration. Quickly, it became a pronounced and ubiquitous feature of Renaissance interior spaces.1 Rather than trace the development and diffusion of this decorative mode or stylistic exercises of fantasia, I would like to present a way of thinking, informed by Michel Foucault’s work, about space itself and about the complex relationships between spaces, as negotiated through the artistic practice of imitation and the Renaissance archaeological imagination.2

The Loggetta of Cardinal Bibbiena in the Vatican (fig. 1), a narrow, vaulted space covered in grotesque decorations designed by the famed Renaissance artist Raphael and his workshop around 1516, provides an intriguing case study due to its mirroring of the form and decoration of the Domus Aurea’s similarly long, vaulted hallway, known as the cryptoporticus (fig. 2). At the time of its discovery, this subterranean ruin had become an example of what Foucault describes as a “heterotopia,” a “different place” at variance with the norms of time and reality.3 The translation and transposition of this space into the Vatican is not, however, a simple anachronism or copy of this heterotopic place. It is a physical product of the Renaissance task of imagining a re-completed and living antiquity, realized through art.

Foucault’s concept of heterotopia seeks to define different spaces in relation to broader cultural norms and social functions. This model assumes that the spaces we inhabit are laden with “bundles of relations” that both demarcate them as discrete and localizable as well as tie them together through proximal connections.4 In this way, space is organized in a manner that makes sense. But within this model there are certain spaces at variance with other sites; these spaces neutralize or reverse these relations with other spaces because they are utterly different. They are heterotopias, or different places.5 They can contain a sense of the uncanny, where time and space are different, where people are expected to behave differently, or where multiple spaces are juxtaposed into one, such as in cemeteries, theaters, or museums.6

The underground ruins of the Domus Aurea can be read as such a location. It exists alongside the history of the city of Rome, yet is locked within a different archaeological stratum. In effect, it is both present and distant, both familiar and alien. An anonymous fifteenth-century artist who visited this place poetically described this experience of difference and the oddities of being there: “[I]n every season the rooms are full of painters. Here summer seems cooler than winter . . . we crawl along the ground on our stomachs, armed with bread, ham, fruits and wine, looking more bizarre than the grotesques.”7 For the Renaissance visitors, the Domus Aurea was a place where time was confused. Here the present and past collided in new temporal-spatial connections and fantastical decoration charged this space with a strangeness that the visitors saw in themselves.

Furthermore, this type of decoration was the antithesis of what the Renaissance had understood as classical and sought to implement through its antique vocabulary. Grotesque decoration, derived from ancient Roman precedents, was employed in fresco or sculpted on walls, ceilings, and architectural frames. It was characterized by hybrids of plant, animal, and human forms; metamorphic and sprawling ornamental candelabra motifs; and illogical and irrational compositions. All of these are noticeable in an anonymous sixteenth-century French artist’s drawings from the cryptoporticus (figs. 3, 4).8 In essence, for the Renaissance viewers, the grotesque presented an inversion of the classical aesthetic ideals of naturalism, harmony, proportion, and rationality of form. And yet this antithesis emerged from the Roman earth and directly out of the classical past, greatly shifting attitudes around this decorative mode through the significance of the discovery of the ruin.9

In the early Renaissance, prior to the finding of the Domus Aurea and before other archaeological projects of exhumation, the work of reconstructing ancient spaces was less architectural. Rather, this reconstruction occurred within the mind and was transmitted through writing and poetry. To Petrarch and his scholarly contemporaries in the mid-fourteenth century, classical truth was indeed buried in deep, inaccessible caverns. Thus, any restoration ought to rely on imagination and literary invention.10 Reading and writing, in fourteenth- and early fifteenth-century humanist philological practices, were the keys to a Roman resurrection—not as a physical location but as an idealized and re-completed mental form based on the contemplation of the material remains.11

However, the work of subsequent fifteenth-century humanists laid the groundwork for a shift from imagination to outward reality. In his work Roma Triumphans of 1459, Flavio Biondo presented a literary construction arguing for a unity of authority between Rome’s pagan and Christian histories.12 This was a mode of thought by which the Roman past would become more clearly part of a contemporary Christian reality through the juxtaposition of the ancient city and early modern theology. Thus, new vigor and expanded license would be added to the project of resurrection that shifted from humanist fiction to a reality mediated by the visual arts and the curation of spaces. The figurative culmination of this project was the letter of Baldassare Castiglione and Raphael to Pope Leo X, written around 1519, where the humanist-diplomat and the artist describe their work of restoring and fleshing out the “lacerated corpse” of Rome as the obligation of the moderns.13 Sixteenth-century artists went beyond the humanist literary imagination, which had conjured a vision of both present and past engendered by the study of ancient materials, and worked instead directly into the physical urban fabric in order to resurrect the body of ancient Rome.

This is what we see in the Loggetta of Cardinal Bibbiena, a space constructed by Raphael14 and decorated by the grotesque specialist of his workshop, Giovanni da Udine.15 Raphael and Giovanni had descended into the heterotopic Domus Aurea sometime around 1510, reemerging with the imagined and idealized mental forms of the spaces they encountered, and transformed these concepts into tangible forms in the current time and space of the Vatican.16 The shape of the Loggetta clearly recalls that of the cryptoporticus and the ethos of the former’s decorations are inspired by the latter’s ceilings and walls in a manner that most closely imitated the original space to date.17 Thin garlands hang between delicate architectural forms, birds and animals perch on curling acanthus leaves, plants transform into animals and faces appear from vegetation. All of this seems to hang in space in an arrangement showcasing the stylistic expansion of the Renaissance grotesque into a largely unbound, full-field mode, set against a plane of white (fig. 5). Similar bird-human hybrids, paired with decorative sea creatures, emerging from ground lines are seen in both the pages of the French sketchbook (fig. 3) and in the top register of a wall segment of the Loggetta (fig. 5). Additionally, the part-plant, winged beasts from the same sketchbook (fig. 4) bear strong visual resemblance to the forms on the bottom register of the same segment. Furthermore, much of the work here was done in the classical rapid technique of grotesque painting, as recorded by Pliny the Elder, wherein an artist works directly on the wall and produces forms free-hand, thus mirroring the ancient manner of execution in addition to the mode of decoration and architectonics.18

Yet this architectural and decorative transposition from the ruins to the Vatican leaves traces of the heterotopia from whence its imagining came within this space. Due to the fidelity of its imitation, this is a place of collapsed time. Indeed it is much like Foucault’s example of the museum, where the decoration from an “anti-classical” classical past haunts and mingles with the present.19 It is also a place of multiple places, as part of a curial apartment suite and a projection of a ruined, subterranean chamber. But the relationship between these spaces is more complicated; here, an understanding of the Renaissance mindset regarding time and art is crucial.20 This period’s valuation of the past allows for what Thomas Greene terms a “creative anachronism,” which is the conscious and productive use of chronological difference in the making of a synchronous present,21 a mode of thought whereby the calculated imitation of classical art already collapses time.22 Thus, this reimagining of the cryptoporticus and the resurrection of its decorative mode and means of execution in effect suspend the heterotopic, temporal difference at play between the Loggetta and the Domus Aurea. They reintroduce some proximal bundles of relations that tie this space to the larger fabric of the Renaissance. This is what lies in between these spaces: an awareness of the past, the desire for re-completion, and the utility of art in mediating temporalities.

____________________

Tyler Rockey

Tyler Rockey is a PhD student at Temple University specializing in the art of early modern Italy. His research interests include the persistence of the classical tradition, Renaissance-era philosophy and theories of art, antiquities collecting, and the physical, temporal, and semiotic instabilities of ancient sculptures in the early modern context.

____________________

Footnotes

1. For comprehensive discussions of the grotesque style of decoration, see Nicole Dacos, La Découverte de la Domus Aurea et la Formation des Grotesques à la Renaissance (London: Warburg Institute, 1969); Clare Lapraik Guest, The Understanding of Ornament in the Italian Renaissance(Boston, MA: Brill Publishers, 2015); and Alessandra Zamperini, Ornament and the Grotesque: Fantastical Decoration from Antiquity to Art Nouveau (London: Thames and Hudson, 2008).

2. James S. Ackerman, Origins, Imitation, Conventions: Representation in the Visual Arts (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 126.

3. Michel Foucault, “Different Spaces,” in Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology, ed. James Faubion (New York: The New Press, 1998), 178.

5. Ibid., 178.

6. Ibid., 181.

7. Michael Squire, “Fantasies so Varied and Bizarre: The Domus Aurea, The Renaissance, and the ‘Grotesque,’” in A Companion to the Neronian Age, ed. Martin T. Dinter and Emma Buckley (Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013), 448.

8. Frances Connelly, “Grotesque,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, ed. Michael Kelly (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), www.oxfordreference.com.libproxy.temple.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199747108.001.0001/acref-9780199747108-e-344.

9. Leonard Barkan, Unearthing the Past: Archaeology and Aesthetics in the Making in Renaissance Culture (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999), 17.

10. Thomas Greene, “Resurrecting Rome: The Double Task of the Humanist Imagination,” in Rome in the Renaissance: The City and the Myth, ed. P. A. Ramsey (Binghamton, NY: Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies, 1982), 42.

11. Roberto Weiss, The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity, (Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell, 1969), 59.

12. Guest, The Understanding of Ornament in the Italian Renaissance, 369.

13. Greene, “Resurrecting Rome,” 43.

14. Dacos, La Découverte de la Domus Aurea, 105.

15. Zamperini, Ornament and the Grotesque, 124.

16. Nicole Dacos, The Loggia of Raphael (New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 2008), 29.

17. Nicole Dacos, Per la Storia delle Grottesche: La Riscoperta della Domus Aurea (Rome: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato, 1966), 48.

18. Dacos, The Loggia of Raphael, 34.

19. Foucault, “Different Spaces,” 182.

20. Aaron J. Gurevich, “Medieval Culture and Mentality According to the New French Historiography,” European Journal of Sociology 24, no.1 (1983): 194.

21. Thomas Greene, The Vulnerable Text: Essays on Renaissance Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986), 221.

22. Alexander Nagel and Christopher S. Wood, Anachronic Renaissance (New York: Zone Books, 2010), 18.

Small Twigs and Withered Plants: Mimesis and Miniaturization in World War I Landscapes

by Tobah Aukland-Peck

A Model of a Devastated Town (1920) (fig. 1) revels in the minutiae of disintegration. The walls of the church in its center are blown out, with its bell tower rising precariously above. Around the church are fallen beams, burned roofs, and dead trees—all meticulously crafted by modelmakers. At London’s Imperial War Museum (IWM), which opened originally at the Crystal Palace in 1920, visitors could lose themselves in the wreckage, searching in vain for survivors, puzzling out the words that remained legible over a shop door, and peering in the gaping windows of the homes still standing.1 Like most miniatures, Devastated Town conjured the enchantment of the real. It sought authenticity by using actual sticks for trees, adding resin to render the river shimmering and reflective, and piling sand and dirt in the road. The tangibility of the materials bolstered a feeling of imminence; a year after the Armistice, British citizens could feel the rage of battle anew.2 This model, which purported to show a French town ruined by enemy bombing during World War I, used its mimetic effect to reconstitute an environment pushed beyond the reach of imagination both by distance and the alienating calamity of mechanical warfare. The haptic proximity of the model was borne, however, from a source closer to home.

The supplies that performed the work of the model’s illusion were sourced from debris of British soil: twigs, plants, sand, and dirt taken from city parks. In this substitution of material experience, the local mimicked the distant violence of war. Twigs picked from British parks metamorphosed into the shell-scarred trees of the French battlefront. The model operated in a physically enclosed world and the objects within had a dual referentiality. They interacted with one another—the twigs that represented the trees in Devastated Town were of like size and depended on collective scale to evoke a realistic space. Yet they also engaged with their counterparts in the real world: the viewer could realize the relationship between the twigs and the trees outside.3 The uncanny nature of the model derived from this simultaneous internal and external signification. By using their imagination to explore the physical world of the model, the viewer treated it like real space—a gesture that bypassed the contradiction of internal realism with external material.

A Model of a Devastated Town was one of approximately fifteen models exhibited at the IWM galleries when they opened to the public in 1920. The newly opened museum evoked the experience of war by combining the actual guns used on the battlefront with paintings, watercolors, and prints by war artists, along with photographs, maps, and models. The miniature scale of the models stood in contrast to the full-size objects—like weapons and regimental banners—that had actually seen combat. Susan Stewart’s work on the ontology of the miniature cites the mediated experience of modernity, in which authentic experience is defined by the “myth of contact,” an imaginary gesture rather than the actual bodily experience of the tangible world. “The memory of the body,” she writes “is replaced by the memory of the object."4 The role of the miniature in the transposition of knowledge from body to mind starts in childhood, when dolls and toys are—like the French village in Devastated Town—animated through the alchemy of material and imagination. This familiarity of the model in early pedagogical exercises for abstract thinking opened up the space of the model as an immersive corollary to these relics of war.

The detail of the models may, at first, link them with the realism of battle paintings in nearby galleries (such as John Singer Sargent’s Gassed [1919]).5 However, the imagination required to animate the models pulled them outside the realm of traditional representation and aligned them, instead, with the most radical experimental image borne of the war: the aerial image. I propose this connection for reasons both practical and theoretical: models in this period were produced based on both aerial photography and topographical maps resulting from aerial reconnaissance. Once the models were installed in the museum, a visitor standing over them would take the place of the aerial eye. The role of scale, an essential aspect of the model’s function as both object and fantasy space, is evidenced in a photograph of visitors at the IWM gathered around the model (fig. 2). The modelmakers ensured that the height of display cases remained consistent and accessible for close contemplation, thereby facilitating a bird’s eye perspective. This was not the view of the soldier but the view of the reconnaissance plane.

The two genres also shared a reliance on imagination as an interpretive and animating force. This way of seeing was particularly relevant to the altered topography of World War I, as subterranean trenches and a reliance on aerial reconnaissance shifted the strategic relationship between space and vision. The view from the ground was limited and unreliable. The view from the air was what mattered.6 If the models provided a familiar entrée to the unfamiliar terrain of war, aerial paintings, as the 1920 IWM catalogue emphasizes, were alienating: “Artists here were guided by no traditions and had to work from eye memory. … They show sights which the imagination must be kindled to realise… It is not to be expected that every groundsman will find air-pictures as lucid as normal landscapes.”7 Notable here is the creative leap. This is a visual strategy that must be learned.

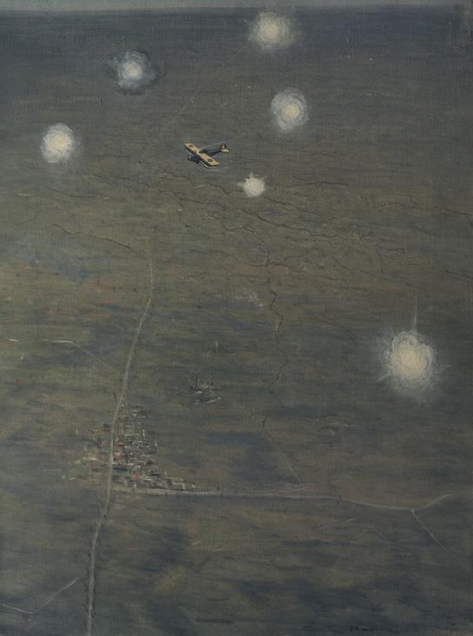

Though battle models have a history that predated the advent of aerial warfare, the physical proximity of A Model of a Devastated Townto aerial paintings and photographs in the IWM galleries recontextualized their format in relation to aerial vision.[8] Images such as Christopher Nevinson’s Over the Lines (1917) (fig. 3)—on display nearby Devastated Town in the Air Force section of the IWM—revealed aerial imagery as schematized rather than representational. Nevinson’s composition has a uniform ground of gray-green and the scant topographical differentiation reiterates the muddy sameness of the front. The staccato lines of white, black, and ochre used to form the town below imply a violent disintegration of the built environment. The horror of war, however, is removed, and the exploding shells in the aerial composition appear as ornamental rather than deadly.

Nevinson’s view incorporated information about roads, trenches, and troops with information indicated by abstract symbols rather than a pictorial match between signifier and signified. The genre of aerial-landscape paintings was facilitated by two mechanical innovations of the early twentieth century that augmented the limits of human vision: reconnaissance flights and aerial photography.9 Its format claimed a scientific lineage which, as the IWM catalogue makes clear, required a trained viewer to make the images lucid.10 Even in the context of an art exhibition, the viewer took on the role of a trained military observer by reading the distant marks of Over the Lines as the details of a ruined town. This is, as the catalogue implies, a drastic departure from the conventions of British landscape painting, where clarity and legibility were highly valued. Landscape imagery, which was vital as an informational tool in past wars, had been rendered obsolete by the symbolic vision of aerial reconnaissance. The explicitness of the miniatures circumvented this troubled relationship between human observation and mechanical vision, presenting a claim for unmediated reality. In the galleries of the IWM, the models translated the remote landscape seen in images such as Over the Lines into a form that reestablished stable topographical vision. Yet their precision and tangibility were an anachronism, and the irony of the models is that they were, unlike aerial paintings and photography, products entirely of the home front.

If authenticity was achieved by some war artists through first-hand experience, the modelmakers, for the most part, had not personally witnessed the episodes or landscapes they were tasked with creating. Instead, for objects such as Devastated Town, the IWM would send the modelmaker maps, aerial photographs, and artist sketches to assist with the production of the scene. Just as the war on the ground became dependent on topographical information gleaned from the air, the maps and photographs used to construct these models in the removed workshops of London were dependent on mechanical vision. The modelmakers had the expertise to translate aerial viewpoints into standard visual conventions. They acted as invisible mediators between the museum visitors and the military, asserting the landscape of war as comprehensible despite the distance from the frontline and the violence of the battle.

The town in Devastated Town was, however, as indistinct as the one in Over the Lines. A later caption notes that the model was intended to represent the war-time condition of a number of French villages and to show the rampant destruction of war to a British populace whose own land, in this period before the Blitz, was relatively untouched.11 Like the nameboard of an obliterated village, the model stood as a record of loss. It showed a landscape that was particular to the war as a whole—as troops and shelling moved through civilian towns in northern France—rather than a specific time or location. The implied reality of the miniature, in its intense detail and promise of a completely enclosed world, seemed to deny its composite nature. Like the literary referents of Barthes’s reality effect, the models marshal excessive detail to conjure a convincing simulacrum of place.12

While the IWM intended to display the efforts of the entire military and civilian population in the war and had sections devoted to domestic efforts, none of the models shown at the Crystal Palace were of British sites. When a modelmaker wrote to the museum to suggest a model of the damage done by the first zeppelin bomb dropped on London, the institution declined, citing space restraints.13 The inclusion of this scene would have disrupted the contrived certainty of models of the war’s terrain. A violent spectacle that had torn through buildings and streets mere miles away from the museum would have broken the enclosure of the models. The safe distance—borne of the models’ aerial viewpoint, miniaturization, and representation of a general type rather than a specific place—would be negated by the immediacy of the local zeppelin damage. The threat of the lived experience would be brought dangerously close to home; imagination would not be necessary to bridge the gap between knowledge and experience.

The simulacra of foreign battlefields were ultimately marshalled as psychological barriers between the field of war and the home front. The clarity of their construction circumvented the necessity of experienced vision required by other documentation of the twentieth century’s first mechanized conflict. They allowed “groundsmen,” as the IWM catalogue notes, to attain lucidity. The models were consistently and repeatedly focused on distant locations and did not threaten the integrity of the British landscape in the face of world war. The supplies that performed this work, however, were physical remnants of the British soil, marking the scene as a foil to the unscathed landscape of Britain. The museum’s lead curator wrote to the superintendent of Hyde Park in 1919:

I beg to inform you that a number of Relief Models showing various portions of the Western Front and War Areas are being prepared by this Department […] To complete these models, it is necessary to insert small twigs and withered plants on a scale suitable to the model. I shall be obliged therefore if you will allow Mr. Ogilvie, the bearer of this letter, to select such small specimens as occasion may demand, it being of course understood that none of these specimens would be taken from flower beds, only from the wilder parts of the park.[14]

Though the miniature world transformed twigs and plants into approximations of foreign terrain, their attachment to British parkland threatened to undo the model’s claim of authenticity. To maintain the illusion of British control over the distant battlefield, it was integral that both the modelmakers, and the war itself, would not disturb the flower beds.

____________________

Footnotes

1. Since 1936, the IWM has been located in Lambeth. The museum vacated the Crystal Palace and moved to South Kensington in 1924. The Crystal Palace at Sydenham was the glass structure designed by Joseph Paxton to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. It was moved from Kensington to Sydenham in 1852.

2. In this way, these models share a history with earlier battle panoramas, such as those exhibited in France and England during the Napoleonic wars. It is important to note that this tradition was modernized during WWI through large-scale photographic panoramas that were similarly intended as mimetic performances; see Martyn Jolly, “Composite Propaganda Photographs during the First World War,” History of Photography 27, no. 2 (2003): 154–65. These experiences, however, were often staged as separate performances, and the models are distinct in their use as part of the newly conceived military museum.

3. Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993), 45.

4. Stewart, On Longing, 134.

5. Gassed (1919) was one of the largest paintings included in the art section of the IWM galleries. Sargent, an American, was commissioned by the British Ministry of Information in 1918 to travel to the front, where he completed research for this work. The painting remains in the collection of the museum.

6. This representational shift is documented by scholars including Bernd Huppauf and Hanna Rose Shell; see Bernd Hüppauf,“Representing Space — Panoramas of World War I Battlefields,” History of Photography 31, no. 1 (2007): 83–84; Hanna Rose Shell, Hide and Seek: Camouflage, Photography, and the Media of Reconnaissance (New York: Zone Books, 2012).

7. Imperial War Museum, Catalogue of Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1920), 4

8. Military wargames, which used tabletop surfaces augmented with topographical details to plan troop movements, were invented in Prussia at the turn of the nineteenth century. They were popularized in England by author HG Wells, who published Little Wars, a guide to tabletop war games, in 1913.

9. Caren Kaplan summarizes the scientific and militaristic implications of aerial vision in her chapter about aerial mapping projects in early twentieth-century Iraq; ee Caren Kaplan, Aerial Aftermaths: Wartime from Above (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 138.

10. Allan Sekula’s article on Edward Steichen’s role as commander of the aerial-photography branch of the American Expeditionary Force during the First World War is an early contribution to the field of aerial photography. His analysis echoes many of the points that I pull from the IWM catalogue caption, including the “rationalized act of ‘interpretation’” that constitutes any visual interaction with the aerial image;see Allan Sekula, “The Instrumental Image: Steichen at War,” Artforum 14, no. 4 (December 1975): 26–35.

11. While the IWM identifies some images of this model as “A Model of Peronne” I believe that this caption, included with the catalogue entry for the model itself, supersedes this later identification.

12. Barthes proposed the reality effect in a 1968 essay. He originally applied it to literary models. He distinguished between textual details that relate specifically to the main plot—called predictive—and details that are descriptive but superfluous to the story, notations. The extraneous details play upon the reader, building an experience that heightens the sense of the text’s reality, see Roland Barthes,The Rustle of Language (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1989), 141–48.

13. Correspondence from Major C. Foulkes to Charles Ledwidge, January 24, 1922, EN1/1/MOD/001, The Imperial War Museum Archive, London.

14. Correspondence from Major C. Foulkes to Hyde Park Superintendent, February 21, 1919, EN1/1/CPL/020. The Imperial War Museum Archive, London.

Phillippa Pitts interviews Mingqian Liu and Amanda Thompson

Editors’ Introduction

by Rebecca Arnheim and Bailey Benson

When the theme of “Environment” was selected for the 36th Annual Boston University Graduate Symposium in the History of Art & Architecture, we could not imagine how profoundly relevant it would be for the year 2020. The year began with bushfires in Australia that burned more than 46 million acres of land. Intense monsoons severely impacted several countries in Asia and abnormally heavy rainfall in Sudan and Ethiopia resulted in devastating flooding. In the United States, wildfires rage more frequently and with greater intensity in the West of the country, tornado season in the Midwest is getting progressively longer, and tropical storms and hurricanes regularly ravage the southern and eastern coastlines. These are only a few examples of the increasingly common natural disasters that have occurred this year. Then, a novel coronavirus hit the world stage.

Global concerns surrounding COVID-19 reached a fever pitch in early March, just weeks before the symposium was scheduled to take place. The venue was set, speakers had booked their travel, and all things appeared to be proceeding as planned. Almost overnight the whole situation changed. It became increasingly apparent that this event, as with so many others, would not be able to take place as scheduled. After serious deliberation with both the faculty members of the History of Art & Architecture Department at Boston University and representatives from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the difficult decision was made to cancel the symposium. This special edition of SEQUITUR features papers from that canceled symposium.

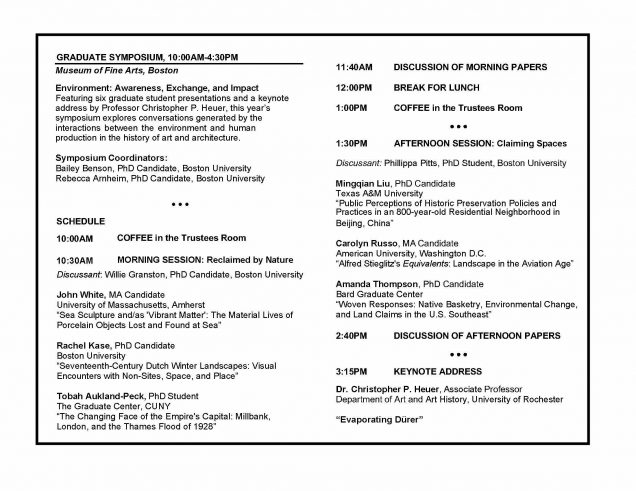

This year’s graduate symposium was planned for March 28, 2020, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. This event was intended to explore the relationship between the environment and artistic and architectural production (fig. 1). Six graduate students from across the country were invited to share their research, and a keynote address was to be presented by Professor Christopher P. Heuer (University of Rochester). The graduate student presenters were: Tobah Aukland-Peck (The Graduate Center, CUNY), Rachel Kase (Boston University), Mingqian Liu (Texas A&M University), Carolyn Russo (American University), Amanda Thompson (Bard Graduate Center), and John White (University of Massachusetts Amherst). The speakers were to be divided into two panels of three presentations each. The morning session, “Reclaimed by Nature,” was to feature papers focused on nature overcoming human creation and artists’ corresponding reactions. While the morning session focused on nature’s triumph, the afternoon was expected to explore human accomplishments against nature’s forces in a session entitled “Claiming Spaces.”

The present issue of SEQUITUR features papers from four of the presenters. The organization of this issue is intended to reflect that of the event itself (fig. 2). The two parts mirror the two panels, and the papers are presented in the order they would have been delivered at the symposium. Two video Q&A sessions were also recorded in which the authors and the original session moderators, Willie Granston and Phillippa Pitts respectively, further discuss the papers.

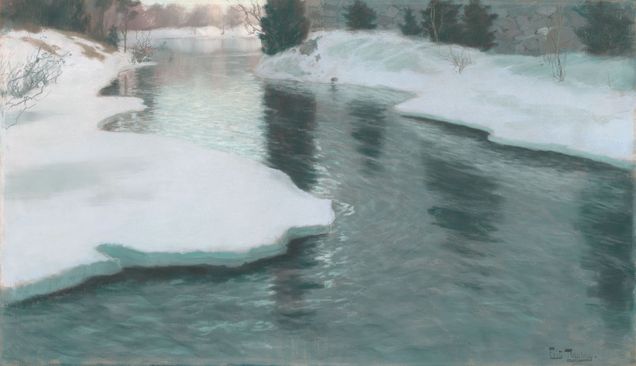

The issue begins with Rachel Kase’s paper, which investigates the Little Ice Age’s artistic representations in Dutch art. Kase demonstrates how the monochromatic representations of winter-obscured landscapes disoriented viewers and created instances of “non-sites” in Netherlandish artistic productions. Tobah Aukland-Peck uses miniature displays of World War I battles on display in the Imperial War Museum in order to explore how British citizens dealt with and understood war events that occurred on foreign soil. The choice of materials used to create these models ultimately came to play a central part in how the war was presented to the British citizenry.

Mingqian Liu looks at the built environment, discussing the impacts of preservation efforts on the residents of an 800-year-old historic neighborhood in Beijing, China. Her paper uses interviews with those residents to argue for a bottom-up approach to preservation practices, one that considers the residents and their daily interactions with their built urban environment. The concluding paper of the issue is by Amanda Thompson and deals with the relationships between objects, their makers, and the collections they become a part of—in this case, the British Museum. Thompson uses the example of an eighteenth-century Cherokee basket to demonstrate Native relationships to the environment through the act of weaving and how baskets come to function as objects of land claims as they move into settler spaces.

We hope that this special issue of SEQUITUR invites readers to rethink their own relationships with their environments, both natural and human-made. How does our environment shape us, and how do we shape our environment? The papers featured in this issue serve as good starting points for conversations that can continue outside of the print medium, generating new dialogues and avenues of investigation.

A Sustaining Cherokee Basket: Colonial Inscription and Indigenous Resistance

by Amanda Thompson

One of my Cherokee elder aunts tells me baskets are living things. She believes the materials she uses in her weaving give the baskets everlasting life. “When we weave a basket, it is held close to our body so as to impart our spirit into the basket. When you give a basket, you give a part of your spirit,” she says.[1]

—Author and poet MariJo Moore (Eastern Cherokee, Dutch, and Irish ancestry) in “The Spirit of a Cherokee Basket”

A large Carolina basket made by the Indians of splitt canes some parts of them being dyed red by the fruit of the Solanum magnum Virginianum racemosum rubrum & black. They will keep any thing in this from being wetted by rain. From Coll. Nicholson Governor of South Carolina whence he brought them.[2]

—Earliest catalogue description of a Cherokee basket acquired by the British Museum in 1753

The two texts which begin this essay communicate disparate understandings of a Cherokee basket.[3] Although written centuries apart, cultural rather than temporal differences separate them. The first presents the conceptions of generations of the author’s Eastern Cherokee ancestors that a basket is a living thing, with a continuous, intimate, and inextricable connection to the sources of its natural materials and to its maker. The second, written to identify an object in the British Museum’s collection, represents the basket, its materials, and its maker as colonized subjects. Considering the object life of that eighteenth-century doubleweave Cherokee basket in the collection of the British Museum (fig. 1–2), I will draw on the tension between these two ways of understanding a basket to weave an essay which unsettles the authority of a colonial institution’s collecting and cataloguing of a Native-made basket and exposes that authority as an agent of settler colonial violence.

Guided by the counsel of Tuscarora art historian Jolene Rickard that “even the most ‘traditional’ form, like basket weaving, is actually a demonstration of Indigenous renewal, survival, and political and environmental awareness,” I aim to access Cherokee basket makers’ “strategic cultural resistance,” and to illustrate how colonial agents acted to neutralize and erase this resistance, conforming to the “elimination of the Native” required by the settler colonial structure.[4] I conclude by considering the maker and, responding to an archival lack, imagine her agency in entering the basket into the colonial networks of exchange and demonstrate how the maker’s act of “strategic cultural resistance” has lived on to renew Cherokee political and cultural agency. As a non-Native scholar, this imagining is in the form of queries, shaped—like all my scholarship—--by what I have learned from many Native thinkers. This mode of narration is influenced by African-American scholar Saidiya Hartman who “exploit[s] the capacities of the subjunctive… both to tell an impossible story and to amplify the impossibility of its telling.[5] My queries aim to illuminate other ways of considering the unknown maker’s agency, without speaking for her.

“The Spirit of a Cherokee Basket”

Basketry is woven into Cherokee cosmological, ecological, ancestral, and community relationships. Historically, women made baskets to be used for trapping, harvesting and processing food, storage, transporting goods, and bartering, among other subsistence activities.Baskets also had ceremonial purposes, such as to protect and contain the power of ritual tools and garments. They feature prominently in Cherokee stories, such as that of Selu, the Corn Mother, who used baskets to catch the corn and beans which she shook from her body to nourish her children, and of Kanane-ski Amai-yehi, or Spider-Dwelling-in-the-Water, who wove a basket to bring fire to the earth.[6] In these stories and practical uses, baskets are sustaining vessels central to Cherokee ways of being.[7]

Basketry has also supported Cherokee continuance. For instance, following the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and subsequent forced migration of thousands of Cherokees, Cherokee Nation scholar Karen Cooper Coody describes:

Upon arrival in Indian Territory, bereft of adequate household items, the vast majority of Cherokee women would have immediately set to work producing a needed array of workbaskets. … Most women were faced with endless tasks of tending sick and weakened families, feeding them, sewing and mending worn-out clothing, weaving new cloth and making quilts, planting household gardens, cooking and foraging in unfamiliar Ozark woodlands or grasslands for plants suitable for food, medicine and craft materials [such as basketry].[8]

After devastating loss, Cherokee women managed their survival by adapting their ancestral art to the materials available in unknown territory.[9] Returning to their tradition of weaving allowed for the renewal and resurgence of peoples—not just through a basket’s utility, but also through ensuring that cultural knowledge could live on, changed but resilient.

Basketry also provides rhetorical means for renewal and decolonization. Cherokee/Appalachian author Marilou Awiakta identifies a doubleweave basket as the “natural form” of her book Selu: Seeking the Corn-Mother’s Wisdom:

As I worked with the poems, essays, and stories, I saw they shared a common base—the sacred law of taking and giving back with respect, of maintaining balance. From there they wove around four themes, gradually assuming a double-sided pattern—one outer, one inner—distinct, yet interconnected in a whole. … Reading will be easy if you keep the weaving mode in mind: over… under… over… under. A round basket never runs “straight-on.”[10]

The complicated process and ultimate strength of doubleweave enables Awiakta to reckon with modern environmental destruction and reweave a restorative vision of futurity for her readers. Similarly, Qwo-Li Driskill uses doubleweave as a structure in their 2016 book Asegi Stories: Cherokee Queer and Two-Spirit Memory, which weaves together personal and theoretical writings to create a third space (“between the basket walls”) in which to decolonize Cherokee-specific traditions of gender and sexuality.[11] Thusly, basketry has sustained Cherokee life and culture through baskets’ practical uses, in the perpetuation of traditions of knowledge, and by providing a framework for resurgence and decolonization—all despite colonial efforts to decontextualize baskets and disenfranchise their Native makers through collecting and cataloguing.

“A large Carolina basket”: Collecting and cataloguing as settler colonial inscription

The catalogue cited at the start of this essay is the earliest known record of the British Museum’s doubleweave basket.[12] Although the writer is unidentified, the language they use to describe the basket illuminates a colonial framework for their knowledge, with idioms encoded to naturalize colonial power. The basket is first identified as a product of a place inscribed with a colonial name: Carolina. The colony of Carolina was granted its charter and named by King Charles II of England in honor of his father, erasing the historic and ongoing identifications of lands by the peoples native to them and instead providing an Anglo-monarchical ancestry.[13] The basket is secondly identified by the generic “Indians” who made it, eliding the diverse Native polities of North America into one undistinguished other.[14] The plant whose dyes provide the basket’s contrasting design is called after Britain’s supposed virgin queen, Elizabeth I, literally overlaying British power onto plants indigenous to the colony, in an act of “linguistic imperialism” which classified and so claimed the plant life of the world.[15]

This cataloguing enacts epistemic violence we now identify with settler colonialism. Citizen Potawatomi Nation scholar Kyle Powys Whyte writes that settler colonialism necessitates “homeland inscription,” as “settlers can only make a homeland by creating social institutions that physically carve their origin, religious and cultural narratives, social ways of life and political and economic systems (e.g. property) into the waters, soils, air and other environmental dimensions of the territory or landscape. That is, settler ecologies have to be inscribed into indigenous ecologies.”[16] Settler colonialism has been inscribed into the archive of this basket by renaming its homelands and the natural materials from which it was woven and by flattening the diverse peoples of Native North America into a single, othered, Indian. This inscription supports the “structural genocide” of settler colonialism through appropriation of lands and assimilation of peoples.[17]

As its maker and community has been excised from its archival record, the written provenance of this basket begins with its ownership by a colonial agent. South Carolina governor Francis Nicholson possibly collected it as a gift from Native delegations, such as when he negotiated the first colonial treaty with Cherokees in 1721. In meetings with the multiple Native communities of South Carolina, Nicholson sought to gain information and establish boundaries and trade relations, while Native delegations took the opportunity to affirm their sovereignty. Gifts like maps and baskets asserted rights by demonstrating Native territories, resources, geographical and ecological knowledge, and existing trade and political relationships. While Native people strategically gifted maps and baskets to make political, economic, and territorial claims in their meetings with colonial authorities in the eighteenth century, other Southeastern Native nations—such as the Chitimacha and the Coushatta—have used baskets to strategically advance land claims into the twentieth century.[18]

Rather than acknowledging the rights asserted with these maps and baskets, Nicholson entered them into a collection supportive of Britain's empire-building project by transferring them to Sir Hans Sloane. A leading London intellectual, Sloane used his position and wealth to comprehensively collect flora and human-made objects from throughout the empire, supported by British agents acquiring local specimens.[19] Sloane collected in order to build knowledge, which in turn supported Britain’s expanding empire and commercial interests.[20] Botanical knowledge enabled the classification, cultivation, and capitalization of the natural products of colonized lands.[21] Objects made by peoples throughout the empire educated British people about colonized subjects and supported an imagined hierarchy of civilization with British culture at the pinnacle and other cultures below.[22]

Upon Sloane’s death, British Parliament complied with his testamentary wishes that the collection be kept together and made publicly accessible by establishing the British Museum in 1753. This progressive move towards public education enabled all those able to visit to observe and learn about world cultures. But the London museum also facilitated the expansion of the logic of colonialism, as visitors could imagine their place at the center of empire and internalize hierarchies of a civilized center superior to uncivilized others which Sloane created in his collection. By spreading the logic of colonialism amongst the public, subjugation, resource extraction, and dispossession were normalized as an inevitable—and benevolent—right of Britain. The transformation of a Native diplomatic gift into an object in a national collection at the center of empire enacted settler colonialism by providing proof of ownership of Native land and of the incorporation of Native peoples at the seat of colonial power.[23]

Conclusion

In resistance to the epistemic violence of settler colonialism which severed this basket from its cultural context, I believe it is powerful to acknowledge the part of the unidentified maker’s spirit given with the basket, recalling the opening words of MariJo Moore. What if she intended this basket to demonstrate Cherokee rootedness in their homelands? What if she staked a claim by mobilizing the knowledge of generations of ancestors who learned to cultivate the land and transform its plant life into a watertight basket? What if she meant to build a relationship through the gifting of this basket, with the expectation of reciprocity and respect, in line with Cherokee relationship-based governance? What if this basket was woven as a material manifestation of Cherokee sovereignty? The intentions and expectations of the maker’s spirit have been excised in the basket’s collection and cataloguing in order to inscribe settler colonialism onto the peoples, land, and ecology from which it came, in another deliberate act of dispossession.

In 1940, Eastern Cherokee basket maker Lottie Stamper used images of this basket to further her knowledge of the doubleweave technique and then teach it to others (fig. 3).[24] In this way, Stamper refused the co-option of the basket by the colonial state, and instead accessed the ancestral knowledge embodied in the basket to enable the technique’s renewal in the community. Eastern Cherokee artist Shan Goshorn, who passed away in 2018, drew from the knowledge revitalized by Stamper and used strips of treaty texts, historical photographs, and other documents to weave paper baskets which spoke powerfully to the injustices of the United States against Native peoples (fig. 4). Goshorn’s basketry demonstrates how an eighteenth-century basket continues to sustain Indigenous renewal and strategic cultural resistance.[25]

____________________

Footnotes

[1] MariJo Moore, “The Spirit of a Cherokee Basket,” Fiberarts 28, no. 4 (February 2002): 25.

[2] “Basket,” British Museum, accessed March 9, 2020, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/E_Am-SLMisc-1218-a-b.

[3] Cherokee peoples are indigenous to homelands throughout the Southeast of the territory now known as the United States. In the nineteenth century, the United States government forcibly moved thousands of Cherokees to Oklahoma to open up land to settlers. Today, there are three recognized tribes of Cherokees: the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians and the Cherokee Nation, both in Oklahoma, and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina—all of whom maintain basketry traditions. In this paper, I refer to the culture both generally and pre-removal as Cherokee.

[4] The basketry quotation comes from Jolene Rickard, “Uncovering/Recovering: Indigenous Artists in California” in Art, Women, California 1950-2000: Parallels and Intersections, ed. Diana Burgess Fuller and Daniela Salvioni, (Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2002), 145. The term “strategic cultural resistance” is drawn from Jolene Rickard, “Visualizing Sovereignty in the Time of Biometric Sensors,” South Atlantic Quarterly 110 (Spring 2011): 474. While in the latter essay, Rickard engaged with contemporary “Haudenosaunee artists [who] visualize sovereignty through key episodic ‘traditional’ or historical moments” (474-75), I find the idea broadly useful in thinking politically and critically about historic and contemporary Indigenous arts. The term “elimination of the Native” comes from a foundational text of settler colonial theory by Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (December 2006): 387-409. Wolfe asserts a “structural genocide” (403) as concomitant with settler colonialism, enacted not just by mass killings but also removal from lands, removal from tribes, enforcement of a grammar of race, and assimilation.

[5]Abridged for length in the body of my essay, I think it necessary to include this quotation in its powerful entirety: “By advancing a series of speculative arguments and exploiting the capacities of the subjunctive (a grammatical mood that expresses doubts, wishes, and possibilities), in fashioning a narrative, which is based upon archival research, and by that I mean a critical reading of the archive that mimes the figurative dimensions of history, I intended both to tell an impossible story and to amplify the impossibility of its telling”;Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 12, no. 2 (June 1, 2008): 11.

[6] James Mooney, Myths of the Cherokee (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1902), 242, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/45634/45634-h/45634-h.htm#s2. Still today “these stories and the teaching that come from them create and maintain the everyday reality for the Eastern Cherokees”; Sandra Muse Isaacs, Eastern Cherokee Stories: A Living Oral Tradition and Its Cultural Continuance (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019), 100.

[7] For information on Cherokee basketry, see M. Anna Fariello, Cherokee Basketry: From the Hands of Our Elders (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2009) and Sarah H. Hill, Weaving New Worlds: Southeastern Cherokee Women and Their Basketry (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1997). It is likely the British Museum basket is actually two separate pieces—a basket and a tray—miscatalogued as one piece due to the similarity of sizes and technique. Anthropologist Betty Duggan believes they might represent the work of two different makers, and resists an absolute attribution to a Cherokee maker, rather than to other peoples indigenous to the region; Betty J. Duggan, “Baskets of the Southeast” in By Native Hands: Woven Treasures from the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, ed. Stephen W. Cook and Jill R. Chancey (Laurel, MS, Seattle, WA: Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, University of Washington Press, 2005), 36.

[8] Karen Coody Cooper, Oklahoma Cherokee Baskets (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2016), 27.

[9] Cherokee makers experimented with the different plants found in Oklahoma and adjusted to their qualities and gathering seasons. Eventually, buckbrush root became the primary basketry material of Oklahoma Cherokees, combined with oak stays. Similarly, Eastern Cherokee basket makers had to adapt to environmental changes wrought by settlers. As cane became less prevalent Cherokee women innovated basketry techniques and designs in oak and root runners in the early nineteenth century, the introduced or invasive Japanese honeysuckle root runner in the later nineteenth century, and fast-growing maple in the early twentieth century. Contemporary makers use all these materials to continue to innovate new forms and designs.

[10] Marilou Awiakta, Selu: Seeking the Corn-Mother’s Wisdom (Golden, CO: Fulcrum Pub, 1993), 34.

[11] Qwo-Li Driskill, Asegi Stories: Cherokee Queer and Two-Spirit Memory (Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press, 2016), 5.

[12] Cataloguing is a practice that museums use to describe objects. It is a step in the acquisition process, as knowing creates ownership. Its classifications impose culturally contingent knowledge upon objects, which continue to determine understandings and access to objects to the present; see Ramesh Srinivasan, Robin Boast, Jonathan Furner, and Katherine M. Becvar, “Digital Museums and Diverse Cultural Knowledges: Moving Past the Traditional Catalog,” Information Society 25 (2009): 265-78 and Hannah Turner, “Decolonizing Ethnographic Documentation: A Critical History of the Early Museum Catalogs at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History,” Cataloguing & Classification Quarterly 53 (August 2012): 658-76.

[13] The colony of Carolina was chartered in 1663 and split into two colonies—North and South Carolina—in 1712. As the singular “Carolina” is used in the catalogue description, it is likely that in England the two colonies were still referred to as one despite their administrative division.

[14] See Jodi A. Byrd, The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism, First Peoples: New Directions in Indigenous Studies (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2011) on the collapsing of diverse Indigenous polities into a racial Indianness as a tool of settler colonialism in the United States.

[15] Londa L. Schiebinger, Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), 195. The acts of classifying plants and cataloguing objects similarly subordinate local knowledge to that of the empire.

[16] Kyle Powys Whyte, “Indigenous Experience, Environmental Justice and Settler Colonialism” in Nature and Experience: Phenomenology and the Environment, ed. Bryan E. Bannon (London, New York: Rowman & Littlefield International, 2016), 171-72.

[17] Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native”: 403.

[18] See Ian Chambers, “A Cherokee Origin for the ‘Catawba’ Deerskin Map,” Imago Mundi 65, no. 2 (June 2013): 207–16; Denise E. Bates, Basket Diplomacy: Leadership, Alliance-Building, and Resilience among the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana, 1884-1984 (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2020); and Daniel H. Usner, Weaving Alliances with Other Women: Chitimacha Indian Work in the New South (Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 2015).

[19] See James Delbourgo, Collecting the World: Hans Sloane and the Origins of the British Museum (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2017) for a history of Sloane’s collecting and the founding of the British Museum anchored in the recognition that Sloane’s wealth in part derived from his slave-holding, demonstrating the foundational link of the British national collection to profits from the subjugation of people and the realities of Britain’s slave-based economic power. For early research specifically into Sloane’s ethnographic collections, see David I. Bushnell, “The Sloane Collection in the British Museum,” American Anthropologist 8, no. 4 (1906): 671-85; H. J. Braunholtz, “The Sloane Collection: Ethnography,” The British Museum Quarterly 18, no. 1 (1953): 23-26, https://doi.org/10.2307/4422413.

[20] See Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), a foundational work of postcolonial theory on how the creation of knowledge enabled imperial power as a form of epistemic violence working in tandem with imperialism’s brute force and material superiority.

[21] See Londa L. Schiebinger, Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004).

[22] See T. J. Barringer, and Tom Flynn, eds., Colonialism and the Object: Empire, Material Culture, and the Museum, Museum Meanings. (London , New York: Routledge, 1998); Elizabeth Edwards, Chris Gosden, and Ruth B. Phillips, eds., Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Culture, Wenner-Gren International Symposium Series (Oxford , New York: Berg, 2006); Amiria J. M. Henare, Museums, Anthropology and Imperial Exchange (Cambridge, UK , New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005); George W. Stocking, ed., Objects and Others: Essays on Museums and Material Culture, History of Anthropology, (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985).

[23] See Curtis M. Hinsley, “Collecting Cultures and Cultures of Collecting: The Lure of the American Southwest, 1880-1915,” Museum Anthropology 16, no. 1 (1992): 12-20. As Indigenous communities and formerly colonized countries today demand the repatriation of objects collected under conditions of unequal power, these assumed hierarchies of knowledge and authority endure particularly in debates over rightful ownership and claims that objects will be in jeopardy if returned to their community of production; see Chip Colwell-Chanthaphonh,“Repatriation and the Burdens of Proof,” Museum Anthropology 36, no. 2 (2013): 108-9,https://doi.org/10.1111/muan.12024; Rosemary Coombe, “The Properties of Culture and the Possession of Identity: Postcolonial Struggle and the Legal Imagination” in Bruce H. Ziff and Pratima V. Rao, eds., Borrowed Power: Essays on Cultural Appropriation (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1997), 74-96; and Neil G.W. Curtis, “Universal Museums, Museum Objects and Repatriation: The Tangled Stories of Things,” Museum Management and Curatorship 21, no. 2 (January 1, 2006): 117-27.

[24] The technique of doubleweave was not dormant in the Eastern Cherokee community at the time, as at least a few women still used the technique. Stamper, however, learned the technique in order to teach it and therefore spread and revitalize its use; Fariello, Cherokee Basketry, 40-43.

[25] See curatorial statement by Heather Ahtone in INTERTWINED, Stories of Splintered Pasts: Shan Goshorn & Sarah Sense (Tulsa, OK: Arts & Humanities Council of Tulsa, Hardesty Arts Center, 2015), https://issuu.com/ahhatulsa/docs/int_cat_issuu, for more on the work of Goshorn.

Public Perceptions of Preservation Policies and Practices in Historic Residential Neighborhood: A Case of Dongsi, Beijing, China

by Mingqian Liu

State-led built heritage preservation efforts started in China in the 1980s, when China joined the UNESCO World Heritage Convention as a State Party and received its first designations on the World Heritage List, including the Forbidden City and the Great Wall.[5]However, similar to the history of preservation in the Western world, it took decades for the Chinese government and preservationists to realize that tangible remains of the built environment were not the only asset worth preserving. Intangible aspects, including cultural identities and living traditions associated with heritage communities and the built environment, had to be taken into consideration as well. Although there was a set of state-issued guidelines regarding strategies and treatment of historic artifacts and buildings (much like the Secretary of Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties in the United States), the official Chinese version of preservation guidelines did not touch much on how to protect the human aspects of the many diverse types of historic built environments.[6] This illustrated that the lack of emphasis on human factors in historic preservation is a global concern.

Since the turn of the twenty-first century, the global field of historic preservation has seen an emerging trend called “people-centered approach."[7] This shift’s roots date back to the Nara Document on Authenticity (1994), where construction techniques and living traditions were deemed worth preserving, especially in non-Western contexts. A people-centered approach suggests that preservationists should not solely care about preserving brick and mortar for future generations, but should instead make people’s wellbeing the central goal of all preservation work. This approach is more sustainable because it involves more stakeholders, pays more attention to the interactions between people and their environments, generates diverse and inclusive solutions for treatment and renovation, and helps to dismantle the oftentimes expert-defined official discourse in heritage values and significance. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, published in 2015, included preserving culture as an important part of building sustainable cities, suggesting that people-centered preservation has already become a globally recognized concept. This paper, which takes a people-centered approach in historic preservation, attempts the first step toward understanding residents’ perceptions of historic preservation and policies, and how they could be more involved in the process. It uses Dongsi, an inner-city historic neighborhood in a developing country, as a case study. Although current residents are not the only stakeholders or human factor in people-centered preservation, they are the group that experiences long-lasting impacts first hand. Taking a bottom-up approach, this paper argues that residents see infrastructure and life quality improvement as the most pressing preservation needs in their neighborhood, and that preservationists need to establish long-term relationships with the community in order to carry out sustainable preservation practices.

Previous scholarly literature has clearly shown that historic preservation is an interdisciplinary field. Architects, urban planners, archaeologists, historians, social workers, and museum and tourism industry professionals work in a collaborative forum where theories, research methods, and working mechanisms intersect. However, this field also lacks a unified framework within which researchers and practitioners can operate.[8]

Previous scholarly writings have demonstrated the importance of the human aspect in heritage conservation and historic built environment preservation. As Dongsi has been designated as a protected area since 1990, the focus of this discussion is on residents’ post-designation concerns and involvement in the continuation of this preservation work. Urban planning scholars have focused on how involving more stakeholders in preservation could help in democratizing the heritage discourse, in other words, extracting diverse values from the built heritage and dismantling the traditionally expert-centered discussion around the “whys” and “hows” regarding our treatment of historic neighborhoods.[9] Because historic neighborhoods are often protected from the real-estate market and are considered part of the public well-fare, scholars of preservation law have emphasized that property owners are not the only demographic impacted by historic preservation.[10] Social scientists and urban policy-making scholars have contributed to the discussion of a people-centered approach, using the concept of “sense of place.”[11] This concept demonstrated how people behave differently in different physical environments (e.g., public versus private spaces). Therefore, one integral aspect of the physical environment (in this case, hutongs and courtyard house neighborhoods) is people’s experience associated with the environment. The “sense of place” literature emphasized intangible aspects, including experience, traditional lifestyle, and practices, as essential values of built heritage. To localize these concepts in a Chinese city, studies have been done in how heritage conservation, especially historic neighborhood preservation, served as an important tool for urban identity and image-building in Chinese cities.[12]

Previous studies have been done on other designated protection areas in Beijing regarding preservation schemes, tourism, and neighborhood change.[13] However, most of the studies took a top-down approach, looking at preservation as solely a government-led effort, instead of as a bottom-up or interactive process in which different stakeholders played different roles.[14] This paper aims to access the public perceptions of historic preservation policies and practices with a focus on residents’ opinions on how neighborhood changes affected their lives, and what impacted their involvement in historic preservation.

As a researcher, I believe that before proposing treatment and accessing the effectiveness of preservation policies and practices, the unavoidable first step is to get to know how residents think of preservation-related issues. They are the group of stakeholders whose lives would be most directly impacted by any kind of preservation action. Therefore, this study utilizes a bottom-up approach to access long-term historic neighborhood residents’ experiences, perceptions, and opinions, using a qualitative analysis method.[15] My study asked the following questions:

- How have existing built heritage preservation policies and practices engaged or failed to engage residents of living heritage communities?

- How have residents been involved in preservation and how can their perceptions contribute to informed actions in future preservation work?

Conversations with the residents often started from an expert point of view, such as values defined in the 2002 conservation planning document approved by the Beijing municipal government.[16] The first two of the five overarching principles of preservation work in these neighborhoods were focused on style and aesthetic features, including preserving the authenticity of streets, historic buildings, traditional courtyard houses, and architectural components. The third principle suggested that renovation or alteration should be done as “microcirculation,” meaning large-scale demolition and construction should be avoided. The fourth principle stated that preservation should work on improving the neighborhood living environment and infrastructure. The last principle made it clear that public involvement should be actively encouraged in historic preservation. In the past two decades, government-led preservation practices have been largely committed to these principles, perhaps with the exception of the third principle, as some large-scale renovations in historic neighborhoods were nowhere near “microcirculation.”

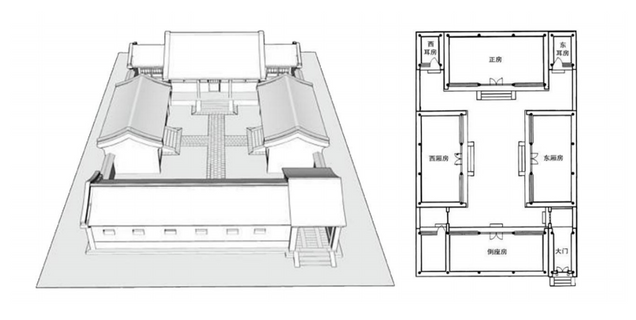

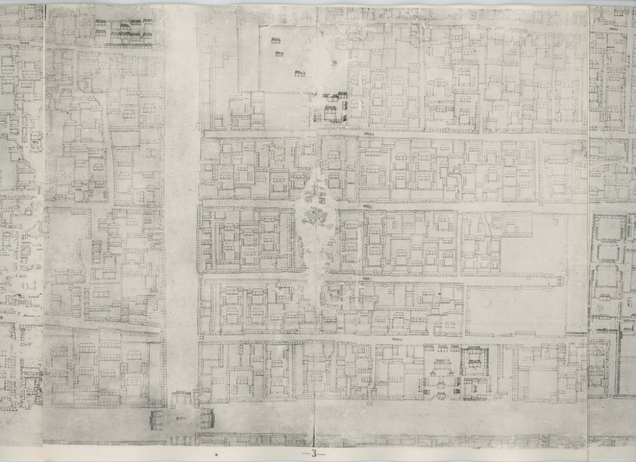

While all the residents interviewed agreed that style and aesthetic features, as shown by the appearance of courtyard houses’ external facades, are important, they did not possess the knowledge to identify what specific style and features are historically appropriate and significant. Many residents admitted that they could distinguish between a traditional and a non-traditional style (figs. 5 and 6) as people continued to make renovation to their houses, and they understand that the historical significance of Dongsi was the primary reason why the neighborhood was designated as worth preserving. However, residents were more concerned about tangible issues in the community, such as infrastructure and life quality improvement in the neighborhood, instead of building appearance or facade changes.

More than half of the interviewees spoke about how preservation practices improved the hutongs they lived in as a desirable public space. The narrow alleyways are not only used for through traffic, but also a place for human interaction, social gathering, and for some residents, their easiest access-point to get in touch with nature.[17] Therefore, when asked about tangible changes brought to Dongsi by government-led preservation campaigns, such as landscape renovation,[18] parking regulation changes,[19] and various measures regarding hygiene and trash collection,[20] residents focused on how such changes affected their use of the hutong as a public space.

Preservation practices did not stop at the public space. Based on the preservation principles, there is more flexibility to change the interior and more private spaces according to the residents’ preference and needs. The interior features of their courtyard houses have been renovated over the years to a contemporary standard, whether renovation was done by the residents themselves or led by various government-initiated campaigns. Inside of the courtyard houses, there were several government-led actions that were widely discussed, such as heating in the winter,[21] electronic wires re-arrangement,[22] and the recent weekend clean-up campaign to check and eliminate fire hazards.[23] This clean-up campaign originated in Dongsi and was promoted throughout the entire district, whereas infrastructure improvements, such as heating, were measures widely implemented in many historic districts with single-floor courtyard houses.

These improvements were mentioned and welcomed by a majority of the interviewees, because they resulted in environment and life quality improvement either in the streets or inside of the residents’ courtyard houses. Some of the changes added additional elements to the physical space, but they were never too conspicuous to interrupt the overall style and features of the historic environment. Compared to treatment and direct actions taken toward buildings and facades, the residents were more likely to understand and support preservation practices targeted at providing much needed functions and spaces for everyday use.

The fifth principle, as previously mentioned, encouraged the active involvement of the public in preservation works. Although it is widely agreed that stakeholder participation is an effective and essential tool in urban planning and people-centered preservation, the degree or level of involvement is often far from being clearly defined. When asked about how preservation practices engaged residents in the process, residents agreed that relationship-building among all stakeholders is important, in order to obtain their understanding and support regarding certain preservation policies and practices.[24]

There were three factors residents suggested really impacted their involvement in preservation. The first was whether there was a commitment to long-term engagement from the government, that include planners, social workers, residents, and other institutions and services in the community. The second factor was how much guidance and recognition residents received from the local administration regarding their involvement in preservation. How residents described the implementation of these two factors suggested that historic preservation was still perceived as a predominantly government-led effort in such neighborhoods, but the residents were willing to work with the public sector as long as they received proper instructions and positive feedback. The third factor many residents pointed to was that implementing a fix-all approach was not helpful. Residents feel that it is important to have professionals come into the neighborhood to work with each individual courtyard house, discuss long-term solutions, and follow up with the residents.

In conclusion, the first step of bottom-up historic preservation research is to understand current residents in addition to the historic physical environment and, furthermore, to support informed actions. This study provides the first step to center people, their experiences, perceptions, opinions, and needs in the process of preservation. Results showed that neighborhood residents care more about infrastructure and the improvement of life quality than the neighborhood’s appearance, style, or facade changes. The latter factors are closely related to the urban history and historic values of this neighborhood. However, even if history and values were conveyed to residents, people who actually live in the neighborhood did not directly benefit from these factors other than having a sense of pride. Residents recognized preservation efforts when appearance changes impacted quality and functions of life. This significant difference is not only a value judgement, but also suggests the potential gap between government-led preservation efforts and the residents’ involvement in both voicing concerns and taking actions to contribute.

Results also showed that various universal and local factors need to be taken into consideration. Conservation planning may follow universal principles, but the social, political, and economic contexts in inner-city historic neighborhoods remind us that the mechanisms of working with local communities need to be specifically designed every time. Planners and preservationists will benefit from getting actively and continuously involved with their target community. Practitioners need to work with each city and its communities’ development patterns, and align preservation with the interests of that particular population.

____________________

Footnotes

[1] See Nancy S. Steinhardt, “The Plan of Khubilai Khan’s Imperial City,” Artibus Asiae 44, no. 2/3 (1983): 137-158.

[2] See Hou Renzhi, Beijing Historical Maps (Beijing, China: Beijing Chubanshe, 1988). [侯仁之,《北京历史地图集》(中国北京:北京出版社,1988)].

[3] See Nancy S. Steinhardt, “Why were Chang’an and Beijing so Different?,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 45, no. 4 (December, 1986): 339-357.

[4] See Beijing Municipal Commission of City Planning, Conservation Planning of 25 Historic Areas in Beijing Old City (Beijing, China: Beijing Yanshan Chubanshe, 2002). [北京市规划委员会,《北京旧城25片历史文化保护区保护规划》(中国北京:北京燕山出版社,2002)]; the jurisdiction of Dongsi Subdistrict (the most local level of government in Beijing Municipality, under Dongcheng District) has a population of 43,731 according to the 2010 Census. The designated protection area is from Dongsi Santiao to Batiao (the Third Alleyway to the Eighth Allyway).

[5] See Yu Kongjian, “China Faces the Challenge of World Heritage Concept: Thoughts after the 28th World Heritage Convention,” Journal of Chinese Landscape Architecture 11 (2004): 68-70. [俞孔坚,《世界遗产概念挑战中国:第28届世界遗产大会有感》(《中国园林》,2004)].

[6] See Jin Hongkui, “The Content and Theoretical Significance of the Principles for the Conservation of Heritage Sites in China,” in Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites, ed. Neville Agnew (Los Angeles, CA: Getty Publications, 2010), 75-84; and ICOMOS China, Principles for the Conservation of Heritage Sites in China (Beijing, China: Wenwu Chubanshe, 2015). [中国古迹遗址保护协会,《中国文物古迹保护准则》(中国北京:文物出版社,2015)].

[7] See Jeremy C. Wells, “Valuing Historic Places: Traditional and Contemporary Approaches,” School of Architecture, Art, and Historic Preservation Faculty Papers 22, (2010).

[8] See Randall Mason, “Assessing Values in Conservation Planning: Methodological Issues and Choices,” in Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage, ed. Marta de la Torre (Los Angeles, CA: The Getty Conservation Institute, 2002); Jeremy C. Wells, “Heritage Values and Legal Rules: Identification and Treatment of the Historic Environment via an Adaptive Regulatory Framework,” Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 6, no. 3 (2016), 345-364; and Jeremy C. Wells and Barry L. Stiefel, Human-Centered Built Environment Heritage Preservation: Theory and Evidence-Based Best Practices, (New York, NY: Routledge, 2018).

[9] See Randall Mason and Erica Avrami, “Heritage Values and Challenges of Conservation Planning,” in Management Planning for Archaeological Sites, (Los Angeles, CA: Getty Publications, 2002).

[10] See J. Peter Byrne, “Historic Preservation and its Cultured Despisers: Reflections on the Contemporary Role of Preservation Law in Urban Development,” in George Mason Law Review 19, no. 3 (2012): 665-688.

[11] See Fatima Bernardo, Joana Almeida, and Catarina Martins, “Urban Identity and Tourism: Different Looks, One Single Place,” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Urban Design and Planning 170, no. 5 (October 2017), 205-216; and John Schofield and Rosy Szymanski, Local Heritage, Global Context: Cultural Perspectives on Sense of Place (Farnham, U.K.: Ashgate Publishing, 2011).

[12] See Ren Xuefei, “Forward to the Past: Historical Preservation in Globalizing Shanghai,” City and Community 7, no. 1 (2008), 23-43.

[13] See Hu Yingjie and Emma Morales, “The Unintended Consequences of a Culture-Led Regeneration Project in Beijing, China,” Journal of the American Planning Association 82, no. 2 (2016), 148-151; Charles S. Johnston, “Towards a Theory of Sustainability, Sustainable Development and Sustainable Tourism: Beijing’s Hutong Neighbourhoods and Sustainable Tourism,” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 22, no. 2 (2014), 195-213; Placido G. Martinez, “Authenticity as a Challenge in the Transformation of Beijing’s Urban Heritage: The Commercial Gentrification of the Guozijian Historic Area,” Cities 59 (November 2016), 48-56; and Hyun Bang Shin, “Urban Conservation and Revalorisation of Dilapidated Historic Quarters: The Case of Nanluoguxiang in Beijing,” Cities 27 (2010), S43-S54.

[14] See Dai Linlin, Wang Siyu, Xu jun, Wan Li, and Wu Bihu, “Qualitative Analysis of Residents’ Perceptions of Tourism Impacts on Historic Districts: A Case Study of Nanluoguxiang in Beijing, China,” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 16, no. 1 (2017), 107-114; and Wang Fang, Liu Xiaoyu, and Zhang Yueyi, “Spatial Landscape Transformation of Beijing Compounds under Residents’ Willingness,” Habitat International 55 (July 2016), 167-179.