Jessica Campbell: Heterodoxy

Fabric Workshop and Museum

October 6, 2023–June 2, 2024

by Corey Loftus

Upon entering Jessica Campbell’s installation in the first-floor gallery at the Fabric Workshop & Museum (FWM), visitors are invited to take a seat. An assortment of antique chairs with blue floral cushions, arranged around three long tables, draw the viewer inward (fig. 1). The room is cozy—in part because of the abundance of fiber-based materials on the gallery’s perimeter, including the bright red fireplace on the rear wall. Canadian artist and cartoonist Campbell fashioned the orange flames, boxy mantle, and even the flowers perched atop the hearth entirely out of commercial carpet and polyurethane foam. On either side, plush tufted panels cover the walls from floor to ceiling. Tufting is a textile manufacturing technique that involves running short pieces of thread “piles” through a taut primary base with a tufting gun (fig. 2). The process produces a surface of densely packed threads that entices the tactile sense. Luckily, the museum offers a textile sample to satisfy viewers overwhelmed with the desire to touch them.

In its totality, the gallery pays homage to the interior of a restaurant called Polly’s, a bohemian mainstay once located on MacDougal Street in Greenwich Village, New York.1 Details like the fireplace derive from historical photographs of Polly’s that Campbell acquired through her research. The radical feminist group of suffragettes and social reformers of the Heterodoxy Club met in the basement beginning in 1912. Members included arts patron Mabel Dodge Luhan (1879-1962), writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860-1935), sex educator Mary Ware Dennett (1872-1947), and civil rights activist Grace Nail Johnson (1885-1976), among others. Unitarian minister Marie Jenney Howe (1870-1934) founded Heterodoxy at the height of the suffrage and labor reform movements that characterized the Progressive Era. Howe and her fellow “Heterodites” (as they called themselves), were instrumental in defining the stakes of gender equality at the exact moment when the modern idea of “feminism” was still in its infancy.2 While many of the Heterodites participated in protests and demonstrations throughout the city, Heterodoxy meetings offered a different, yet complementary, form of activism. At weekly luncheons, members debated issues in the company of other women. Their discussions addressed the rights to vote, organize, acquire contraception, and dress freely in gender nonconforming clothing. Given the controversial nature of these conversations, Heterodites kept their membership secret and prohibited records of any meetings.

Campbell conceived of Heterodoxy during her 2023 residency at the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Center City, Philadelphia. Upon receiving this competitive residency, artists receive full access to the FWM studios where they collaborate on creative projects with the in-house staff of trained artists. In addition to tufting, Campbell worked with the FWM staff to silkscreen the floral patterns on the seat cushions and to build the complex exhibition design.3 Not only does Campbell’s exhibition cast a spotlight on the history of the Heterodoxy Club, but it also clearly argues for the literal and metaphorical necessity of semi-private spaces provided by restaurants, speakeasies, art galleries, church basements, parks, and other similar locations for political discussion and organizing efforts to flourish. The tables and chairs in the center of the gallery serve a dual function, commemorating Howe’s feminist club while also inviting new forms of social interaction.

Campbell is a writer, cartoonist, and artist who, as already briefly noted, works with rather unusual materials—carpet, foam, felt, pompoms, found textiles, and even, as of late, car wash mitts. Her carpet paintings, collages, and installations function similarly to her cartoons: they deliver satire and wit in delicious forms of plush over-exuberance. In fact, cartoons and carpets establish the crucial links between Campbell’s practice and the historical legacy of the Heterodoxy club. Within the space of the exhibition, she directly cites and draws inspiration from the work of two Heterodites in particular: textile artist Ami Mali Hicks (1867-1954) and feminist cartoonist Annie Lucasta “Lou” Rogers (1878-1952). While Hicks promoted do-it-yourself crafts for functional domestic objects, Rogers published biting political cartoons advocating for women’s equality.

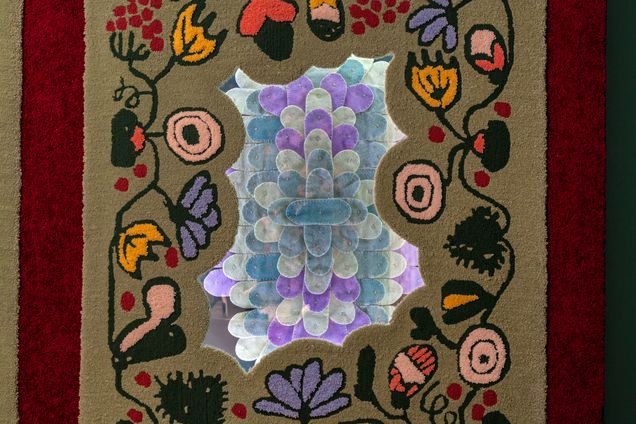

In 1914, Hicks published a handy textile guide for amateurs called The Craft of Hand-Made Rugs. This instruction manual progresses the nineteenth century Arts & Craft Movement ethos that making functional objects by hand countered the mechanization and degradation of design threatened by the industrial revolution. Hicks encouraged her readers to save their money by making rugs for their homes from a variety of patterns using cheap or scrap materials that could already be found lying around the house. The Craft of Hand-Made Rugs exemplifies her commitment to the democratization of knowledge and the potential joy that can be found in making useful everyday objects.4 In a nod to Hicks’s textile practice, Campbell derived the tufted floral design for her wall panels from a rug pattern she found in a photograph of Hicks in her Greenwich Village shop by photographer Jessie Tarbox Beals. Additionally, Campbell reproduced two versions of Hicks’s “Scalloped Doormat or Tongue Rug” design from her 1914 manual. This rug comprises reinforced units of oblong shaped fabric layered, based on Hicks’s instructions, like shingles on the roof of a house (fig. 3).5 Pleasing the average FWM visitor’s desire to champion craft, Campbell hangs these do-it-yourself style rugs vertically on the walls like paintings, upending the hierarchy of the fine arts in one swift curatorial maneuver.

After spending enough time in the gallery, visitors will soon notice that the rugs drift in and out of view. Campbell installed two-way mirrors throughout the room that darken according to a time schedule. The changing transparency adds an air of mystery but also renders the glass reflective, which, according to FWM’s chief curator D.J. Hellerman, speaks to the process of research.6 Often, scholars and artists alike project their own interpretations onto the objects they find in the archive, suggesting that the act of interpretation requires the negotiation of objective and subjective forces.

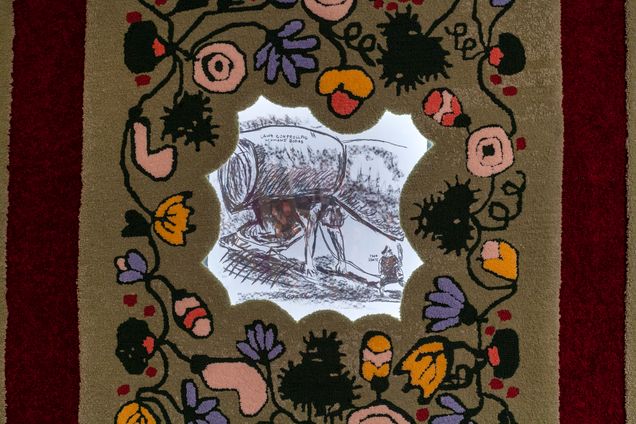

Campbell features two examples of Lou Rogers’s cartoons enlarged to the size of a poster on the same wall as the Hicks-style doormats. Rogers spent her professional career committed to feminist causes as an illustrator and editor for Margaret Sanger’s Birth Control Review. One such illustration she made for Sanger’s May 1919 issue titled “Her Legal Status” depicts a woman carrying an enormous weight on her back as a policeman standing in for “the state” waves a bat and pulls at her neck with a leash (fig. 4). Like Atlas’s great burden, she hauls a colossal scroll labeled “Laws controlling women’s bodies.” Though Rogers published this cartoon over a century ago, viewing its reproduction in the FWM feels disturbingly uncanny. Such a graphic declaration of the burden legislation poses on women’s bodies could have been plucked from this month’s issue of The New Yorker.

Joanna Scutts’s recent social history Hotbed: Bohemian Greenwich Village and the Secret Club That Sparked Modern Feminism (2022), which builds on Judith Schwarz’s foundational research on Heterodoxy, points to the club’s newfound resonance in our contemporary moment.7 Not only does this focus on the Heterodoxy club potentially recuperate queer histories in the context and goals of first wave feminism, but it also models a form of collectivity that thrived on difference and disagreement.

While Scutts and Schwarz’s scholarship on the Heterodoxy Club depends on rigorous research aimed at filling in the gaps or concentrating on the individual biographies of group members, Campbell’s memorialization takes a different approach. The exhibition includes a large display of member portraits on the gallery’s east wall. Though these are entirely fictional representations of Heterodites, the uniformity of medium and gridded display evokes a wall of painted or photographed membership portraits one might expect to find at the Yale Club. But rather than lay claim to prestige or legacy, Campbell deploys an abstract visual language in bold color with an unpretentious felt marker to satirize the haughtiness and exclusivity of club memberships in general. These figures are neither identifiable nor framed, thus protecting the identities of the Heterodites and affirming their ephemerality.

Through the anonymity of the stylized Heterodite portraits, Campbell handles the history of Heterodoxy with a care that honors their secrecy. Yet Campbell stages this series around a gathering, bringing forward Howe’s early twentieth-century vision of community as a political act. Given the centrality of tables and chairs in this exhibition, one wonders if Campbell also had Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party (1974-79) in mind during her residency. Despite the controversy Chicago sparked with her vulvic “central core imagery” and the criticism the work provoked surrounding race and gender essentialism, The Dinner Party remains an enduring monument to craft as an art form and feminist tactic. Like Chicago’s installation and the collective nature of its production, Campbell’s exhibition depended on the collaborative efforts of the team at the FWM. At this point it would make sense to conclude with the suggestion that Campbell’s work improves and builds on the art, activism, and criticism of past feminist eras exemplified by Heterododxy’s ties to the Suffrage movement and The Dinner Party’s alignment with the second wave. Rather than packaging these works as products of their specific historical moments in linear progression, Jessica Campbell: Heterodoxy offers an alternative way of thinking about feminism’s history and future. Instead of making room for women at the metaphorical table, Campbell approaches history with an interest not only in learning the Heterodoxy Club’s secrets but in honoring the original members who wanted to keep some for themselves.

____________________

Corey Loftus is a PhD student at the Institute of Fine Arts focusing on surrealist art in Europe and the Americas. She received her MA from Tufts University and her BA from the University of Pennsylvania.

____________________

1. Chelsea Dowell, “Village People: Polly Holladay,” Village Preservation Blog, Village Preservation, August 9, 2016, https://www.villagepreservation.org/2016/08/09/village-people-polly-holladay/.

2. As Nancy Cott notes, the term “feminism” did not emerge in the United States until around 1910 when it gained traction through the suffrage movement. Nancy F. Cott, The Grounding of Modern Feminism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987).

3. One of the most involved parts of this project was the construction of the false walls created behind the tufted panels where Campbell embedded objects behind panes of two-way mirror glass. Corey Loftus, in discussion with DJ Hellerman and Jessica Campbell, February 9, 2024.

4. Notably, the book’s dedication reads “For everyone who works for the joy of working.”

5. Ami Mali Hicks, The Craft of Hand-Made Rugs (New York: McBride, Nast & Company, 1914), 53-4.

6. Corey Loftus, in discussion with D.J. Hellerman and Jessica Campbell, February 9, 2024.

7. See Joanna Scutts, Hotbed: Bohemian Greenwich Village and the Secret Club That Sparked Modern Feminism, (New York: Seal Press, 2022), and Schwarz, Radical Feminists of Heterodoxy (Lebanon, N.H: New Victoria Publishers, 1982).