news

Sensory Entanglements: Knowledge Rituals in the Digital Age

by Elise Racine

In the liminal space between the physical and digital realms of human thought and creation, our relationship with knowledge undergoes a profound transformation. Through this series of works, I examine how emerging technologies reshape not just our access to information, but the very physicality of our engagement with it. Together, these pieces explore the sensory dimensions—touch, sight, sound—of contemporary knowledge transfer, asking how the digital age reshapes materiality, intimacy, and the archive while situating the viewer at the crossroads of tradition and innovation. The transition from bound volume to infinite scroll represents more than a shift in medium—it fundamentally alters our sensory and cognitive relationship with knowledge itself.

Figures 1-3. Elise Racine. A Book by Any Other Name (2024), Folio Fragments (2024), and Field Guide Distortions (2024). Digital collages involving archival images, photography, digital art, and artist-generated annotations.

A Book by Any Other Name (fig. 1) juxtaposes a weathered physical tome with its digital counterpart, highlighting how artificial intelligence reinterprets the essence of “book-ness.” The textured, ornate cover of the book—a Bible from ca. 1602—stands in stark contrast to the sleek, minimalist e-reader interface. Still, both objects serve as vessels for human knowledge and demand their own form of tactile engagement. The artist-generated yellow frames mimic the bounding boxes used in AI object detection. The accompanying annotations reveal how algorithms “see” and interpret visual information, highlighting elements the system identifies as significant. The boxes have the added benefit of drawing attention to how our eyes and fingers must navigate differently across these surfaces. Here we engage with the tension between physical and digital tactility—between the controlled, bounded experience of turning a page and the potentially endless scroll of digital content.

Meanwhile, Folio Fragments and Field Guide Distortions (figs. 2-3) employ fragmented compositions to further examine how digital media disrupts traditional ways of organizing and accessing information. Building again on the pattern of AI annotations, these pieces feature yellow boxes that highlight the tension between machine and human interpretation. The geometric abstraction framing the original archival image in Folio Fragments causes new details and patterns to emerge. In Field Guide Distortions, this effect is captured by AI annotation boxes whose contents and borders dissolve into pixels and halftone displays, further blurring the distinction between digital and analog representation. As vibrant colors bleed across these boundaries, the image becomes a metaphor for the chaos and the creativity inherent in digital knowledge systems.

Figure 4. Elise Racine. [Crow]dsourced (2024). Digital collage involving archival images, photography, and digital art.

By placing a traditional ex libris crow within the frame of an early personal computer, [Crow]dsourced (fig. 4) reflects on the shift from individual, physical possession to shared, digital knowledge generation. Historically a mark of ownership, the ex libris bookplate is recontextualized in an era of collective authorship and the crow, long symbolic of intelligence and memory, suggests our enduring drive to gather and share knowledge, even as the means of doing so evolve. Meanwhile, the fragmented hand in the corner speaks to the intimate gestures, or human “touch,” that persist in these virtual spaces and the collaborative nature of such acts.

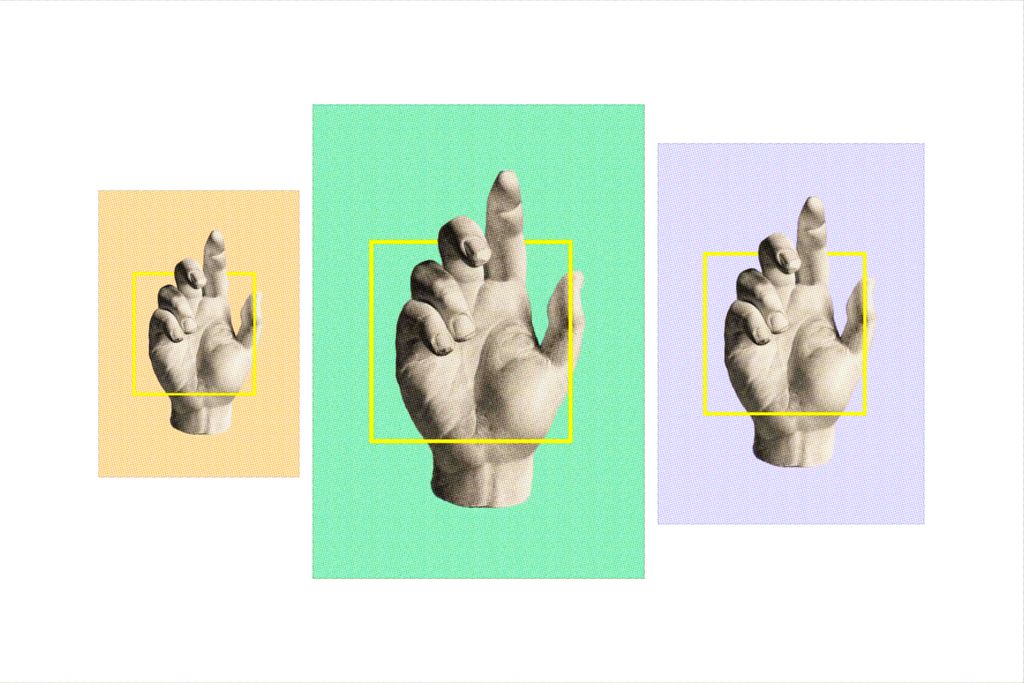

Figures 5-6. Elise Racine. At the Altar (2024) and Holy Trinity (2024). Digital collages involving archival images, digital art, and artist-generated annotations.

In At the Altar and Holy Trinity (figs. 5-6), we again see the hand. Originally a symbol of religious iconography, it now also mirrors the anatomical positions for scrolling, swiping, and liking. These actions—scroll, swipe, like—form a modern “holy trinity.” While digital interfaces may seem to distance us from the materiality of knowledge, we must also consider how they create new forms of sensory engagement, ones that merge historical devotional gestures with contemporary, technologically mediated rituals.

Figure 7. Elise Racine. On Loop (2024). Video art playing on an infinite loop.

On Loop and Scroll A(n)d Infinitum (figs. 7-8), extend this exploration, particularly the destabilizing, distortive nature of digital consumption, with motion and sound. Both were previously on view as Infinite Objects video prints in Boundless: An Exhibition of Book Art hosted by the Arts Galleries at the Peddie School in New Jersey.1

On Loop captures TikTok as a contemporary vessel for knowledge-sharing, pairing the hypnotic feed with an audio soundscape of clicks and taps. Through its fragmented structure, the piece mirrors how our attention splinters across infinite content streams. Scroll A(n)d Infinitum critiques the infinite scroll as a digital reading experience by featuring a long-form article endlessly looping, with glitch aesthetics and chromatic aberrations visualizing the sensory overload of contemporary interfaces. As text fragments blur and degrade, nearly reduced to a binary code of 1s and 0s, the piece highlights how machines can now “read” these digital texts even as they become illegible to human eyes. With the rise of Large Language Models, it poses the question of whether we are creating digital content not just for human consumption, but for an emerging audience of artificial readers—algorithms that process and interpret our knowledge in ways fundamentally different from human cognition.

These moments of friction are precisely why the relationship between physical books and digital interfaces is so compelling. This goes beyond how our fingers engage differently with each medium to how we navigate and control our progression through content and how these sensory interactions shape our reading experience. I strive to recreate the sensation of “doomscrolling,” a phenomenon that arises from the absence of natural endpoints that we find in traditional reading material. The slight discomfort or disorientation viewers might experience navigating this essay points to our larger cultural moment of adjustment to these evolving forms of knowledge transmission.

This work invites viewers to consider not just how we read and learn in the digital age, but how these new practices reshape our fundamental relationship with knowledge—at once more immediate and more mediated, more accessible and more fragmented, more tactile and more ephemeral. Perhaps most striking is how contemporary knowledge is simultaneously in a perpetual state of transition yet immortalized in the digital ether—forming new archives that train the next generation of machines.

Figure 8. Elise Racine. Scroll A(n)d Infinitum (2024). Video art playing on an infinite loop.

____________________

Elise Racine is a Washington, DC-based multidisciplinary activist, emerging artist, and PhD candidate at the University of Oxford. Using arts-based methodologies, her research examines the socio-ethical implications of emerging technologies, like artificial intelligence. Recent exhibitions include: The Bigger Picture (Beta Festival 2024, Ireland) and Unearthing (Sims Contemporary, NYC).

____________________

1. Infinite Objects are freestanding displays housed in acrylic that permanently loop one video. They can be picked up and handled, allowing viewers to physically engage with otherwise ephemeral digital media. In other words, they make the ephemeral tangible again.

Multisensory Experiences in Thomas Jefferson’s Plantations

by Mya Rose Bailey

I first heard the ringing of the Great Clock at Monticello in the dead of summer. The deep, steady resonance of the gong felt as though it could wipe the sweat from my back. I stared as its hammer, now muffled but still deafening in its strike, emanated three low reverberations. And then my three o’clock tour began. I was brought to Monticello by my Master’s thesis, which was concerned with how time and sound were constructed in two of Thomas Jefferson’s plantations in efforts to control Black enslaved labor. By exploring the sensory experience of enslavement through material culture and decorative arts, there is an opportunity to mentally deconstruct objects designed to present unnatural systems—such as race-based enslavement—as intrinsic and necessary to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century life.

Designed by President and enslaver Thomas Jefferson, the Great Clock still stands, as it did for Antebellum audiences, as a marvel of Jefferson’s ingenuity and creativity. Its wooden double-faced body serves as a daily point of reference for internal and external viewers. Once allowed inside Monticello, audiences of the Great Clock can determine the exact time of day through a visible hour, minute, and second hand (fig. 1). Outdoor witnesses, however, only see a single hour hand on the clock’s exterior face (fig. 2). The Chinese gong housed on the roof of Monticello chimes the corresponding hour, reverberating across six miles of the plantation, according to Peter Fossett, one of the nearly six hundred Black people Jefferson enslaved in his lifetime.1

The gong sonically enforced a schedule of labor that could be heard and followed voluntarily by anyone present but was involuntarily heeded by the enslaved community. A constant awareness of the gong’s count signaled when a day’s work began at dawn and ended at dusk, as well as breaks for meals, curfews, and allotted “free” time.2

Monticello in Charlottesville, Virginia and Poplar Forest in Bedford County, Virginia were Jefferson’s most prominent homes and plantations, with a combined ten thousand acres of farmland and nearly two hundred people at a time enslaved across both. To aid in managing this scale of property, Jefferson designed, deployed, and depended heavily on time-keeping and time-telling devices to organize and communicate work schedules to all present laborers.3 Time-telling is best exemplified by objects such as the Great Clock, as its grandeur, permanence, and immovability demand recognition as the standard of regulation in its positioned environment. Multiple case and shelf clocks were also present in more intimate settings for enslaved laborers, specifically the kitchens at both Monticello and Poplar Forest.4 The striking difference between the timekeeping devices’ scale in these spaces suggests the ability of clocks to oversee the bodies, acting as tools of regulation as opposed to entertainment. In contrast to the Great Clock—which would have both delighted and fascinated free visitors to Monticello—these small clocks governed and maintained enslaved bodies and their labor.

One can imagine the rhythmic ticking of a shelf or case clock within the soundscape of a kitchen often occupied by a single cook. The Jefferson family would have set expectations for when a meal should be served, as signalled by the swinging of a hammer chime. Such meals — which would have been made countless times by Monticello cooks — were created both through embodied knowledge and alternative modes of timekeeping (song, prayer, etc.)

This request for a prepared meal at Poplar Forest was commanded by a single brass bell rung by Jefferson that was later excavated from Poplar Forest’s main house.5 The disembodiment of these sounds, and the labor Jefferson demanded through them, is essential in understanding how linear perceptions of time and constructed soundscapes were presented as intrinsic to the hundreds of people he enslaved.

Jefferson’s own understanding of time as both linear and irretrievable was largely informed by European philosophers within the Age of Enlightenment and cultivated his disdain for idleness.6 Jefferson’s subsequent compulsion for efficiency manifested in strict schedules for himself, his family, and the people he enslaved. This temporal imposition was likely disorienting due to the fact that in the Bight of Biafra, where most of his enslaved laborers were taken from in the eighteenth century, time was regarded as unregulated and multidirectional.7 This encourages us—in the contemporary moment—to reconsider the ways enslaved people may have measured, felt, and sounded time within a day. Most importantly, it begs a reconsideration of how we and Jefferson expect time and the sensorium to function for enslaved people. Jefferson himself noted the vibrancy of music and nightlife of those he enslaved in his only full-length book, Notes on the State of Virginia, stating “a black, after hard labour through the day, will be induced by the slightest amusements to sit up till midnight, or later, though knowing he must be out with the first dawn of the morning.”8 The presence of music—specifically music at night, away from the audible demands of labor—suggests another layered soundscape that was not only experienced communally amongst the enslaved but produced by and for themselves as well.

My approach to the sensory experience of enslavement rests upon the acknowledgement that Monticello, Poplar Forest, and the consequent soundscapes of these plantations are all, even loosely, predicated upon slavery in that they only exist because of and to maintain enslavement. Thus, in my interpretation of these constructed temporalities, landscapes, and soundscapes, it is critical to remember there is nothing natural about enslavement. This notion extends to the devices used to both organize and naturalize its practice. Utilizing the senses, especially sound, as both a mode and subject of study permits a more complete picture of the conditions of slavery, both in the ability to place ourselves in the physical landscape of enslaved people and to deconstruct social, cultural, and physical systems that have aided in the dehumanization of enslaved people.

____________________

Mya Rose Bailey (they/she) is an Afro-Caribbean scholar interested in multisensory anthropology, temporality, and memory in Black history and culture. They hold a BA in Art History from SUNY New Paltz and are currently completing their MA in Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture from Bard Graduate Center.

____________________

1. Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, “Behind the Scenes: Conservation of Jefferson’s Great Clock,” YouTube, 2021. 5:18–5:31, https://youtu.be/c14pjuikHRs?si=JYXg9x-niaLcgaKv.

2. Karen E. McIlvoy, “Traces of Jefferson’s Time at Poplar Forest,” Poplar Forest Archaeology Blog, April 7, 2017, https://www.poplarforest.org/traces-jeffersons-time-poplar-forest/.

3. Art Historian Wu Hung differentiates between time-keeping and time-telling, noting “[t]ime keeping relies on horology and astronomy that allowed governing bodies to regulate seasons, months, days, and hours,” while “[t]ime telling conveys a standardized conventional time to a large, general public.” Wu Hung, “Monumentality of Time: Giant Clocks, the Drum Tower, the Clock Tower,” Monuments and Memory, Made and Unmade, ed. Robert S. Nelson and Margaret Rose Olin (University of Chicago Press, 2003), 108.

4. McIlvoy, “Traces of Jefferson’s Time at Poplar Forest.”

5. “Servant Bells at Poplar Forest,” Poplar Forest Archaeology Blog, February 4, 2016, https://www.poplarforest.org/servant-bells-at-poplar-forest/.

6. McIlvoy, “Traces of Jefferson’s Time at Poplar Forest.”

7. McIlvoy, “Traces of Jefferson’s Time at Poplar Forest.”

8. Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries, 2006), 139, https://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/jefferson/jefferson.html.

Conjuring the Spirit World

Peabody Essex Museum

September 14, 2024–February 2, 2025

by Angelina Diamante

A sincere recognition of the ephemera spanning nearly a century that defines Conjuring the Spirit World: Art, Magic, and Mediums—a five-month-long survey of Spiritualism at the Peabody Essex Museum of Salem, Massachusetts—requires a deliberate surrender to nonnormative faculty: in essence, a sixth sense. Composed of an array of posters, projections, photographs, paintings, illusions, film fragments, sculptures, advertisements, and apparatuses, the exhibition’s artifacts incite an active engagement of all the senses, diminishing the boundaries between them and prompting a reconsideration of the very nature of perception.

In addition to evoking clairvoyance in its most fundamental form, this new sense possesses a duality; through the inciting of a historical prescience of sorts, transportation to a past world that engaged magicians and mediums alike is viable. Thus, viewers become vessels for transmuting the sensuous perceptions of visual culture of the nineteenth-and-twentieth-century Spiritualism movement in the modern day. Integral to this effect is the exhibition’s reliance on an array of bold, large-scale magician advertisement broadsides; what were once instrumental in destabilizing the periphery between the spectral realm and the early-twentieth-century psyche now grant contemporary viewers insight into a world where belief was fundamental. The vibrant Do Spirits Live? (fig. 4), promoting the spirit paintings of magician Howard Thurston, and the striking Miss Baldwin, a Modern Witch of Endor (fig. 5), featuring female clairvoyant Kitty Baldwin, epitomize the visual and textual iconography of Spiritualism in popular consciousness. Perhaps all the more imploring are those advertisements that offer a contrary perspective; while the exhibition’s 1929 centerpiece—a poster of Thurston clutching a skull (fig. 6)—boldly asks, “DO THE SPIRITS COME BACK?”, a 1909 print featuring a smirking Harry Houdini presents a stern rebuttal: “HOUDINI SAYS NO - AND PROVES IT” (fig. 7). This juxtaposition underscores the intricacies and partitions within a culture often retroactively regarded as one-dimensional, thereby challenging modern assumptions by revealing the ways in which reality and spectacle harmonized with the senses, achieving resolution with audiences of the present.

As George H. Schwartz, the PEM’s Curator-at-Large, states, “belief is at the core of [the exhibition],” affirming the psychic sentiment behind Conjuring the Spirit World. By interrogating the complex mechanics of perception and identity, this exhibition implores viewers to strive beyond a passive observation: not only through a sensorial engagement with the enchanting objects at hand or a retrospective regard for the Spiritualism movement, but, more crucially, through a critical reexamination of the broader implications of belief in understanding the modern world.

____________________

Angelina Diamante is an MA candidate at Sotheby’s Institute of Art (Valedictorian, with distinction) and a specialist in Italian Renaissance and Baroque European painting and sculpture. Recently, her research has considered art and its intersection with the esoteric and occult, evincing motifs such as classical paganism and the Gothic.

____________________

From Perfume to Smoke: Transforming Salubrious Scents in a Renaissance Perfume Burner

by Madison Clyburn

A classically inspired bronze incense burner from a Paduan workshop, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, speaks to the multi-sensory meditations that once occurred in an early modern Italian home (fig. 1).1 This particular incense burner measures just over a foot tall, is pyramidal in shape, and is comprised of four different parts: base, central column, drum, and finial (fig. 2).2

Like rising perfumed smoke, the decoration is aligned vertically and its fantastical satyrs, sphinxes, grotesque masks, and scalloped shells invoke Bacchic theatricality. The incense burner’s form and iconography derive from the famed Italian sculptor Andrea Riccio’s (ca. 1470–1532) humanistically informed Paschal Candelabrum (1507–16), made for the Basilica of Saint Anthony in Padua.3 Such erudite iconography was popular in Padua—a city celebrated in the sixteenth century for its humanist culture, bronze production, and medical university.

The transformation of a solid perfume into smoke through the application of fire had a multi-dimensional effect on the Renaissance home and body. In the early modern period, scented air was critical to maintaining good health; the affective, ephemeral substance, infused with the divine power of plants, drifted through city streets and infiltrated domestic halls and bodies, influencing the health of those living in Padua.4 Today, this incense burner is admired solely as an art object, devoid of its once fragrant social life. Centuries earlier, though, one would likely find it in a home, infusing a camera (multipurpose bedroom) or studiolo (study) with salubrious scents.5 Within such a space, the Renaissance user would place dried perfume (sticks or pastilles) in the incense burner’s internal compartment or external apertures and set them aflame. The resulting embers would subsequently release energizing swirls of aromatic smoke while tossing delicate light across the bronze surface, encouraging the scholar to meditate on the dramatic transformation unfolding before them. This once-fragrant object—truly a feast for the senses—exemplifies the Renaissance humanist’s philosophical interests, urban lifestyle, and desire for good health.

The New York incense burner’s iconographic pattern mirrors the humanist antiquarian’s interest in the philological and archaeological evidence of the classical past.6 From the bound and rugged satyrs to the wise and alluring sphinxes, these creatures blur the line between coarse animal and cultivated human, philosophically questioning an individual’s true nature.7 The hybrid imagery encourages the owner’s contemplation of the concept of transformation—an idea made vividly real by the metamorphizing act of burning a solid pastille or incense stick into smoke. The transient, sweet-smelling vapor that would curl up and around the burner, together with the object’s iconographical design, conjure a multi-sensorial fantasy appealing to upper-class consumers residing in sixteenth-century Padua.8

Attached to the corners of the base are feet made from satyr masks surmounted by a bound satyr (fig. 3). In his Sileni of Alcibiades (1515), the Dutch humanist Erasmus (ca. 1468?–1536) deviates from the satyr’s classical association with lust and mischief.9 Instead, he argues that if the satyr Silenus is “opened,” that is, his divinely interior self is unbound, he reveals his “great and lofty spirit worthy of a true philosopher.”10 Three decorative plaques alternate between the satyrs’ bound spirits; each one depicts a classicizing Bacchic mask with deeply set forehead wrinkles, wild, twisting hair, and a curled tongue flanked by bunches of grapes, signaling its relation to the fantastical concept of the grotesque (fig. 4).11 Meanwhile, the bordering fruit marks the transformation of grapes to wine but also from sobriety to drunkenness.12 This transition allows one to access the permeable state of divine “madness,” described by the priest and Neoplatonist philosopher Marsilio Ficino (1433–99).13 In his commentary on Plato’s Symposium titled De amore (On Love; 1469), he meditates on the soul’s continuous rise and fall through four states: Intellect, Reason, Opinion, and Nature. Bacchus’s drunkenness, and by extension, the Renaissance humanist’s intellectual inebriation activated through meditation on the smoldering incense burner, simultaneously draws the scholar to the lower world of the senses—smell, taste, and touch—and the higher world of the mind.14 In this revelatory state, inspired by Neoplatonic philosophy, the humanist’s cerebral drunkenness illuminates his rational soul, allowing him to perceive God more closely.15

Attached to the central column are a triad of alternating volutes and winged sphinxes—classical symbols of wisdom and death—with a scalloped shell nestled between their wingtips.16 The figures recall the sphinx from the ancient Greek tragedian Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex.17 Each female hybrid’s scrolled feet unfurl into lion’s fur incised on the base and torso as lusciously layered, feathered bird wings taper into the bust and head of a woman (fig. 5).

In Renaissance architectural style, sphinxes often merge architectural forms with female bodies. In this case, the sphinxes’ lion paws are transformed into miniature volutes. Together with the full-size volutes, they figuratively support the pierced, gadrooned drum above.The third tier features a series of arched windows that allow fragrant smoke to pass through. Laurel festoons fill the space between each opening, topped in the middle with scalloped shells—classical and Christian symbols indicative of transformation and rebirth.18 Like the Greek sphinx, who challenges those she meets to a riddle on the transformation of human life, the symbolic shell may also signal the owner’s mystical journey.

The top of the incense burner showcases a finial in the form of a satyr whose relaxed posture, vacant expression, pitcher of wine, and discarded panpipes suggest the drunken revelry of Dionysus or Pan (fig. 6). However, the satyr’s soft and elongated limbs, distinctive from those of the energetic and tightly bound satyrs at the base of the burner, suggest that this finial was made separately and added later.19 The original finial is likely a statuette of a satyr and satyress copulating like that found on a sixteenth-century Paduan inkwell cover (fig. 7).

An eighteenth-century illustration of a Paduan pyramidal perfume burner (fig. 8) from the same workshop as the New York incense burner helps us imagine its original esoteric theatricality.20 The initial finial suggests the humanist scholar’s interest in philosophy and the cathartic transformation from the captive body to the unbound soul and its harmony with nature, or simply a taste for the erotic in a period saturated with amorous images of satyrs and satyresses in pastoral settings.21

Once burned, the intoxicating and energizing aroma of agarwood, benzoin, cedar, and clove-scented pastilles or sticks would waft up from the perforated heads of the bound satyrs and rising sphinxes (fig. 9) and out of the dome’s arched windows to envelope the satyrs atop the burner. The scented air continues upward, past the ambiguous but symbolically loaded finial, and up to God or a higher principle.

We must imagine—as historical audiences would have understood—the scented air eventually permeating the humanist’s porous body, sitting nearby. After entering the body, the aromatic molecules course through the scholar’s arteries and travel to the brain and heart. In doing so, scented air, facilitated through the use of a perfume burner, infuses the individual’s pneuma (air or life force) with salubrious scents to nurture the soul.22

The sixteenth-century Paduan would have been cognizant of the stimulating, therapeutic effects of scent in a city teeming with students, pilgrims, rubbish, disease, and fragrant imports. Academic and economic influences from Venice and the Levant contributed to Padua’s olfactive mindfulness during this time. When our unknown maker fabricated the New York incense burner, the University of Padua (founded in 1222) was already internationally renowned as a center for medical innovation. Andrea Vesalius’s (1514–64) anatomical text, De humani corporis fabrica (1542), corresponds with the Professor of Practical Medicine, Giovanni Battista da Monte’s (1489–1551) hands-on clinical teaching and the 1595 opening of the first permanent anatomical theatre.23 In 1545, the Venetian Republic founded the first teaching botanical garden for students enrolled at the University of Padua (fig. 10).24 In this erudite atmosphere, professors combined theory and practice using translated ancient Greco-Roman and medieval Islamic texts by Aristotle, Galen, and Avicenna and specimens from the University’s botanical garden to teach about the transformative power of therapeutic scents.

Knowledge of perfumed medicines reached Padua primarily through the Republic of Venice, given its political control of the city since 1404.25 Venice—a cosmopolitan maritime center that thrived on trade relationships with Levantine mercantile partners—imported a variety of aromatics such as aloeswood, musk, civet, and ambergris from Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, and Cyprus.26 These substances were transported to nearby Padua for distribution to various institutions and vendors, allowing students and long-term residents to purchase ready-made perfumed pastilles, pastes, waters, and oils and “simples” (single ingredients) to create perfumes at home using tried-and-true recipes. A genre of books called Libri di Secreti (Books of Secrets) provided many perfume recipes to use in an incense burner, such as ones “to make a fragrant perfume to scent the house” and a “moist perfume for the room.”27 Both recipes from Giovanventura Rosetti’s Notandissimi secreti de l’arte profumatoria incorporate fragrant ingredients admired for their medicinal properties, including rosewater, aloeswood, olibanum, styrax, cloves, sandalwood, and cedar. Many recipes never made it to the printing press but existed in household manuscripts. Recipes for “soft perfumes in pans to scent rooms,” “perfumes to burn in ten ways,” and a “very noble room perfume” indicate ways to burn inspiring, transportive, salutary scents in domestic spaces.28

Surrounding oneself with sweet-smelling air was critical to maintaining or correcting one’s health—physically, spiritually, and mentally. The fortifying properties imbued in the air also played a crucial role in creating healthy, protective, and pleasant homes. The New York incense burner invites us to consider its placement among other coveted but ephemeral aromatic goods made of fragrant plant and animal-based substances complete with “personal, cultural, and social meaning” used to beautify and sanitize upper-middle-class Italian homes in the early modern period.29 For example, perfumed pastilles sheltered in bed warmers encouraged soothing sleeping quarters; floral-scented powders sewn into pillows placed on one’s lap while sewing transported them to fields of roses; while a pungent, disinfectant mix of pitch, styrax, and myrrh scrubbed over walls and floors secured dwellings against infectious air.30 Such perfumed mixtures act as transformative intermediaries capable of offering pleasure and protection. Considering this, the owner of the New York incense burner might set alight aromatic pastilles or sticks for a myriad of reasons, such as tempering the air, regulating the bodily humours, energizing the brain, fortifying the heart, stimulating sex organs, and meditating on metaphysical questions.31

Suppose we imagine a humanist scholar, like this ecclesiastic (fig. 11), sitting in his study, surrounded by books and antiquities, contemplating the philosophical text in his hand while some spiritual imbalance unsettles his humors.32 In that case, the incense burner’s presence on a shelf or desktop speaks to the myriad transformative abilities of perfume. Emblematic of a thriving academic community’s interest in wellness, sixteenth-century Paduan incense burners reflect a sensorial appreciation for tactile delights and tasteful homes mediated through perfumed air.

____________________

Madison Clyburn is an Art History PhD Candidate at McGill University. Her work focuses on medicinal perfumes and the material culture of women’s wellness in late medieval and early modern Italy. She has written for The Recipes Project, Ornamentum magazine, and the SSHRC-funded project Hidden Hands in Colonial Natural Histories.

____________________

1. Unless otherwise indicated, translations are the author’s.

The burner’s manufacture from a wax sculpture to its bronze casting is loosely attributed to Desiderio da Firenze (active Padua, 1532–45), who worked in the Veneto around the time of its creation, or an unknown Paduan workshop. Twelve variations of pyramidal and drum perfume burners produced in this Paduan workshop are located in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (invs. 41.100.78a-d and 1982.60.108); National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. (unknown inv. number and inv. 1942.9.140); the Wallace Collection (S66); the Victoria and Albert Museum (M.677-1910); the Rijksmuseum (BK-1957-3); the Louvre (OA.7406, .8256); and the Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig (unknown inv. number). Drum burners are found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (invs. 1975.1.1396 and 1975.1.1397) and the Ashmolean Museum (WA2004.1).

2. I do not address the incense burner’s casting technique in this essay. For an analysis of the New York incense burner’s casting technique, see Madison Clyburn, Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts Object File (ESDA/OF), the Metropolitan Museum of Art—a study I wrote in a Bard Graduate Center seminar on bronzes held at the the Met and taught by Denise Allen, Elyse Nelson, and Jeffrey Fraiman in Spring 2020.

3. Giovanni Battista de Leone (ca. 1480–1528), Niccolò Leonico Tomeo (1456–1531), and Livio Maggi da Bassano (active 1506)—three of the five Humanists who served as massari (presiding members) on the Council of the Arca del Santo—contributed to the Paschal Candelabrum’s iconographic program, which promoted complex theological and philosophical concepts. The Candelabrum was meant to mark the first light of Christ on Easter morning. Read philosophically, the candle’s flame is akin to divine light, which “illuminates the intelligence and kindles its innate appetite at the very moment when, moved by love, it turns to God.” See Davide Banzato, “Riccio’s Humanist Circle and the Paschal Candelabrum,” in Andrea Riccio: Renaissance Master of Bronze, eds. Denise Allen and Peta Motture (The Frick Collection, 2008), 41–45, 58. For an image of Riccio’s Candelabrum, see Web Gallery of Art, https://www.wga.hu/html_m/r/riccio/candelab.html.

4. According to the proto-feminist Venetian author, Moderata Fonte (1555–92), “…God has even thought to place these [assistive] powers in plants to aid us in our infirmities. How grateful we should be!” See Moderata Fonte, The Worth of Women, ed. and trans. Virginia Cox (The University of Chicago Press, 1997), 168 for the complete passage. On the importance of “healthy” air, see Sandra Cavallo and Tessa Storey, Healthy Living in Late Renaissance Italy (Oxford University Press, 2013), especially “Chapter 3: Worrying About Air,” 70–112.

5. The studiolo had many functions in sixteenth-century Italy: it was a room for reading, writing, introspection, sociability, business, and diplomacy but also a curated space that functioned as the “innermost secret chamber of an individual’s personal world”; see Chriscinda Henry, Playful Pictures: Art, Leisure, and Entertainment in the Venetian Renaissance Home (Penn State University Press, 2021), 43. On the relationship between an individual’s studiolo, their possessions, and mental stimulation, see Stephen Campbell, The Cabinet of Eros: Renaissance Mythological Painting and the Studiolo of Isabella d’Este (Yale University Press, 2004), 31–32.

6. Robert Weiss, The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity (Basil Blackwell, 1988), 59.

7. Jessica Hughes, “Dissecting the Classical Hybrid,” in Body Parts and Bodies Whole, eds. Katharina Rebay-Salisbury, Marie Louise Stig Sørensen, and Jessica Hughes (Oxbow Books, 2010), 109.

8. While many of these tabletop perfume burners were used in Northern Italian homes, international students and tourists from England, France, Germany, and Poland (to name a few locations) likely purchased similar burners to take back to their home countries. On the demand for small, luxury, utilitarian bronzes that decorated upper-class homes in sixteenth-century Italy, see Denise Allen and Peta Motture, eds., Andrea Riccio: Renaissance Master of Bronze (The Frick Collection, 2008) and Peta Motture, The Culture of Bronze: Making and Meaning in Italian Renaissance Sculpture (V&A Publishing, 2019).

9. Ovid offers a more traditional account of the satyr in his Metamorphoses, describing “old Silenus, drunk, unsteady on his staff; jolting so rough on his small back-bent ass,” amid a Bacchanal. Ov., Met. 4.1.

10. Italics mine. Erasmus, “Adages: 1 Sileni Alcibiadis / The Sileni of Alcibiades – 100 Intersecta musica / The music is cut off,” in Collected Works of Erasmus: Adages: II vii 1 to III iii 100, trans. R.A.B. Mynors (University of Toronto Press, 1992), 263. For the satyr’s various meanings in early modern humanist culture, see Anthony Parr, “Time and the Satyr,” Huntington Library Quarterly 68, no. 3 (2005): 451–53.

11. For an overview of the concept of the grotesque in early modern Italy, see Alessandra Zamperini, Ornament and the Grotesque: Fantastical Decoration from Antiquity to Art Nouveau (Thames & Hudson, 2008). On the metamorphizing aspect of the grotesque, see Luke Morgan, “The Grotesque and the Monstrous,” in The Monster in the Garden: The Grotesque and the Gigantic in Renaissance Landscape Design (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).

12. For Bacchus’s role in early modern philosophical conceptions of drunkenness, see Charles H. Carman, “Michelangelo’s ‘Bacchus’ and Divine Frenzy,” Notes in the History of Art 2, no. 4 (Summer 1983): 8, and Florence M. Weinberg, The Wine & the Will: Rabelais’s Bacchic Christianity (Wayne State University Press, 1972), 45–52.

13. Marsilio Ficino, Commentary on Plato’s Symposium on Love, trans. Sears Jayne (Spring Publications, 1985), 168–71.

14. The Italian humanist philosopher, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–94), influenced by Neoplatonic theories of metaphysical unity and the Soul, suggests that Bacchus, the “leader of the muses, in his own mysteries, that is, in the visible signs of nature, will show the invisible things of God to us as we philosophize, and will make us drunk with the abundance of the house of God.” See Pico della Mirandola, On the Dignity of Man, trans. Charles Glenn Wallis (Hackett Publishing, 1965), 13–14.

15. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Platonism and Neoplatonism influenced humanist thought, art, music, and literature, especially through the concept of Beauty. The contemplation of Beauty stimulates the soul’s transcendence through the material world to achieve revelation in a spiritual one. See, Umberto Eco, History of Beauty, trans. Alastair McEwen (Rizzoli, 2005), 48–51, 90 and Paolo Euron, Plotinus, Neo-Platonic and Christian Conception of Beauty (Brill, 2019), 25–28, 41–45.

16. Yuan Yuan, The Riddling Between Oedipus and the Sphinx: Ontology, Hauntology, and Heterologies of the Grotesque (University Press of America, 2016), 51–52. On the sphinx motif in Northern Italian bronzes, see Charles Avery, “The Riddle of the Sphinxes,” in Il Bresciano Bronze Caster of Renaissance Venice (1524/25-1573) (Phillip Wilson Publishers, 2020).

17. The earliest extant version of the story is found in the Greek scholar Athenaeus of Naucratis’s Deipnosophists (c. 200 CE). The riddle goes: “On earth there is a two-footed and four-footed creature, whose voice is one. / It is also three-footed. It alone changes its nature of all the creatures / Who move creeping along the earth, through the sky or on the sea, / But when it walks relying on the most feet, / That is when the speed in its limbs is most feeble.” Sophocles, Oedipus Rex, trans. David Mulroy (University of Wisconsin Press, 2011), 91–92.

18. Shells’ association with a “mystical journey” derives from ancient Greek and medieval Christian narratives. In the classical tradition, shells signify Venus’s birth from the sea and subsequent transport to land via a scallop shell. In Christian practice, scallop shells have long been used as pilgrim badges to represent a pilgrim’s physical and spiritual journey. See, Rebekah Compton, Venus and the Arts of Love in Renaissance Florence (Cambridge University Press, 2021), 215-216, and Ann Marie Rasmussen, Medieval Badges: Their Wearers and Their Worlds (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), 123–126.

19. Without X-ray fluorescent (XRF) testing on the entire incense burner, we cannot determine if the bronze’s metal content is uniform or different in each of the four parts, preventing a definitive answer as to its homogenous manufacture. See Robert H. Tykot, “Investigating Ancient “Bronzes”: Non-Destructive Analysis of Copper-Based Alloys,” in Artistry in Bronze: The Greeks and Their Legacy (XIXth International Congress on Ancient Bronzes), ed. Jens M. Daehner, Kenneth Lapatin, and Ambra Spinelli (The J. Paul Getty Museum and Getty Conservation Institute, 2017), 289–299.

20. Nineteenth-century European cultural modesty led to the hasty creation of more decorous finials. For an explanation on the finial’s offensive iconography and replacement, see Jeremy Warren, The Wallace Collection Catalogue of Italian Sculpture: Volume One (Paul Holberton Publishing, 2016), 294–95; Tilmann Buddensieg, “Die Ziege Amalthea von Riccio und Falconetto,” Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen (1963): 148–50; Bernard de Montfaucon, Supplément au livre de l’antiquité expliquée et representee en figures Vol. I (Paris, 1724), 139–41. For a drawing of the original finial with smoke emanating from the top in a similar dome-shaped perfume burner, see “Drawing of a perfume burner, sent from Hamburg to the abbé de Montfaucon in Paris in 1718,” (Cabinet des Médailles, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; photo Bertrand Jestaz) reproduced in Jeremy Warren, Medieval and Renaissance Sculpture in the Ashmolean Museum: Volume 1 Sculpture in Metal (Ashmolean Museum Publications, 2014), 202.

21. On the production and dissemination of erotic imagery in sixteenth-century Italy, see Sara F. Matthews-Grieco, “Satyrs and Sausages: Erotic Strategies and the Print Market in Cinquecento Italy,” in Erotic Cultures of Renaissance Italy, ed. Sara F. Matthews-Grieco (Ashgate, 2010), 19–60. By nature of utilitarian bronze objects’ multifunctionality, it is important to note that the original finial’s erotic imagery of a copulating couple may speak to its potential use as a therapeutic object in which prescription aphrodisiacs meant to encourage male and female fertility were burned.

22. Though Hippocrates, Plato, Aristotle, and Galen all differ to varying degrees in their beliefs on the origin and location of the soul within the body, they all agree that pneuma is a vital substance, necessary for life.

23. For more on Padua’s medical curriculum, see Jerome Bylebyl, “The School of Padua: Humanistic Medicine in the Sixteenth Century,” in Health, Medicine, and Mortality in the Sixteenth Century, ed. Charles Webster (Cambridge University Press, 1979), 344–45.

24. By the end of the sixteenth century, the University’s botanical garden contained more than one thousand species of medicinal and non-medicinal plants. See Elsa M. Cappelletti, “The Botanic Garden of the University of Padua 1545-1995,” Botanic Gardens Conservation News 2, no. 4 (1994): 23–6.

25. After the War of the League of Cambrai (1509–17), the Republic of Venice effectively managed Padua’s educational activity. Fabio Zampieri, Alberto Zanata, Mohamed Elmaghawry, et al., “Origin and Development of Modern Medicine at the University of Padua and the Role of the ‘Serenissima’ Republic of Venice,” Global Cardiology Science and Practice no. 2 (2013): 151.

26. Leah Clark, “From the Silk Roads to the Court Apothecary: Aromatics and Receptacles,” in Courtly Mediators: Transcultural Objects between Renaissance Italy and the Islamic World (Cambridge University Press, 2023), 196–262.

27. “A far profumo odorifero da profumar una casa” and “Profumo humido per camere,” in Giovanventura Rosetti, Notandissimi secreti de l’arte profumatoria… (Venice: 1555), 7, 48.

28. “Profumi Molli in Padellette per odorare le stanze” and “profumi da Abbrucciare in dieci modi,” Wellcome Collection, London, MS.485, ff. 124-6, 213-5; “Profumo camere nobilissimo,” BNCF, Florence, Palatino 915, f. 8r.

29. Paula Hohti Erichsen, Artisans, Objects, and Everyday Life in Renaissance Italy (Amsterdam University Press, 2020), 39.

30. For scented wall and floor cleaners, see Fabrizio Nevola, Street Life in Renaissance Italy (Yale University Press, 2020), 91.

31. The central tenet of Hippocrates’s humoral theory relies on balancing the four bodily fluids: blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm. Humoral theory differs from Galen’s complexion theory, in which the body’s combination of heat, moisture, coldness, and dryness determines a person’s temperament—sanguine, choleric, melancholic, and phlegmatic—and overall balance tempered by food, drink, cosmetics, medicine, and air, each believed to contain degrees of hot, dry, cold, and wet. For more, see Noga Arikha, Passions and Tempers: A History of the Humours (Ecco, 2007).

32. This room’s contents—books, vases, a bronze bell and candlestick, a carved face, a figurine, and boxes, including one of medals—evoke an appreciation of the classical past. They also reveal the sitter to be an educated and cultivated man of the Church well-versed in humanist collection practices in a time where classical philosophy and Christianity co-existed. For a reanimation of this drawing using the 1586 inventory of the Venetian patrician, Francesco Duodo (1518–1592), see Dora Thornton, A Scholar in His Study: Ownership and Experience in Renaissance Italy (Yale University Press, 1997), 38.

Sensorium: Stories of Glass and Fragrance

Corning Museum of Glass

September 7, 2024–February 23, 2025

by R.J. Maupin

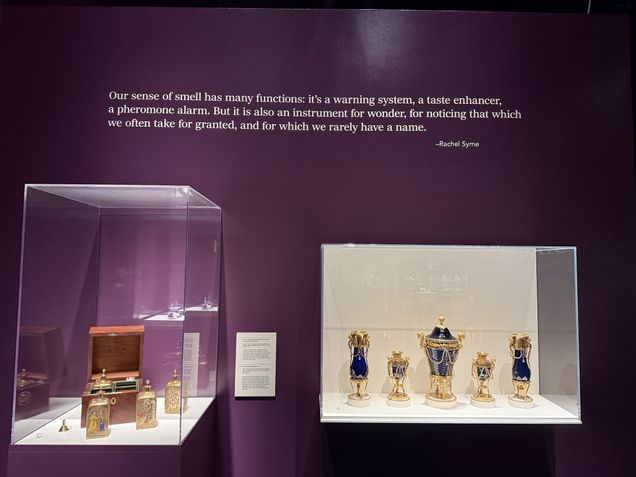

Museum visitors can spend countless hours looking at artwork on display, but other sensory experiences, such as smelling or touching, are largely forbidden. Despite these necessary protocols that protect material culture for future generations, curators can implement creative strategies to facilitate immersive, multisensory exhibitions. Sensorium: Stories of Glass and Fragrance, a 2024–2025 exhibition curated by Julie Bellemare at the Corning Museum of Glass (fig. 1), provides an expansive overview from antiquity to the present day of scent containers that held perfumes, scented waters, medicines, tobacco, spiced oils, and dried flowers. Given that these fragile glass bottles must be protected by vitrines for their safety, the exhibition runs the risk of prohibiting the visitor from engaging the very sense that structures its thematic narrative. Nevertheless, Bellemare cleverly addresses this challenge and offers an encouraging example of how curators can supersede the visual by inviting visitors to “think” with their noses.

Outside of the main gallery is an introductory text and a small interactive station that reminds the viewer to imaginatively consider olfaction in tandem with vision (fig. 2). Under a wall text that asks, “What did money smell like in the 1700s?” viewers are prompted to consider the influence and violence of the European spice trade in Indonesia and Sri Lanka as they sniff spiced oils made from cinnamon, clove, nutmeg, and mace. This method of multisensory engagement seems almost obvious, given its popularity in other recent exhibitions, such as Five Senses of Chinatown at the Museum of Chinese in America and Our Senses: An Immersive Experience at the American Museum of Natural History. However, the danger of this strategy is turning experience into pure spectacle or eschewing a rigorous analysis of the objects. Since Sensorium’s smell station lies outside the main gallery and relates to a carefully selected set of scented oil bottles and potpourri vessels on the adjacent wall (fig. 3), it becomes a thoughtful, generative experience. While the visitor might yearn to smell other relevant materials, it would be challenging to make interactives for each of the works on display. Thus, it was a clever decision to use this station as an ode to a sensorial way of thinking rather than a central facet of the exhibition’s narrative.

After passing through this introductory section, viewers enter the main gallery, featuring deep purple walls and dramatic lighting that evokes the opulence of the colorful glass vessels within display cases. Three wall didactics chart the evolution of scent bottles, investigating histories of industrialization, luxury, and artistry. Cases in the center of the room diverge from the chronological displays, explaining distillation methods, religious uses, and the utilization of herbs and spices for medicine. This exhibition’s small space does not allow for a comprehensive show, but it does offer a diversity of topics, ranging from the attar industry in India, to the development of synthetic scents, to the nineteenth-century belief in the miasma theory. Viewers, then, can rely on their emotive memories of scent to easily find objects or narratives that spark personal intrigue.

Perhaps the most successful element of this exhibition, considering its institutional context in a renowned glass museum, is the exploration of the connections between scents and the materiality of glass. Physically, the impermeability of glass renders it an ideal container, but its fragility also reflects the preciousness of the expensive materials it is designed to hold. Some objects within the gallery require little contextualization to communicate this idea, such as a set of miniature glass bottles in a gold box, which depicts glassblowers crafting a vessel at a furnace (fig. 4). The maker’s decision to replicate this scene reveals how the box’s craftsman, glassmaker, perfumer, and consumer were consciously bound in an intimate relationship. While the visitor cannot physically handle this object, it is easy to imagine the original seventeenth-century owner touching it, picturing the complex methods used to produce the glass vials, and finding pleasure in its lavish aromas.

Beyond historical examples, Bellemare’s inclusion of contemporary glassmakers was a wise strategy to compel the viewer to consider smell as a primary way we interact with the material world. Glass artist Katherine Gray’s Paper, Sleeve, Wax, Block (2024) depicts four tools used to blow glass and small vials holding distilled scents of those that are emitted when using the tools in a hot shop (fig. 5). For example, the block is a wooden tool submerged in water that is used to gently shape the glass; as steam rises off the wood, it emits an unmistakable burnt odor. By capturing these smells, Gray refers to the nostalgia of her embodied experiences as a maker. Gray’s piece makes a powerful statement in this context, as visitors to the Corning Museum of Glass have the opportunity to see (and smell) a live demonstration of glass being blown or flameworked in nearby studios. In harmony with the exhibition’s title, Gray’s work—as well as many others that were selected for display—allude to the necessity of thinking beyond the visual and the meaningful stories we can tell when considering other forms of sensory stimuli in our everyday lives.

____________________

R.J. Maupin is a second-year master’s student in Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture at Bard Graduate Center. Her focus is American glass history of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries with particular interests in labor, industrialization, gender, and the performative aspects of craft.

____________________

editor’s introduction

by Rachel Kline and Kaylee Kelley

The discipline of art history has often struggled to reanimate what, for many of us, are three-dimensional objects stripped of their original context within the white walls of the modern museum. In the field of Renaissance art history, Michael Baxandall attempted to revive the temporally specific viewer with his concept of the “period eye,” which he theorized as the ways in which visual experience is culturally relative.1 However, the full range of sensory engagements beyond the visual was still missing from this approach. More recently, in her study of Isabella d’Este’s collection— an exemplar assemblage of art and artifacts curated by one of the most influential female patrons of the Renaissance— Geraldine A. Johnson has expanded on the concept of the “period eye” by considering the embodied experience of a historically specific viewer who “would have engaged works of art with all the senses, rather than by vision alone.”2 She argues that the tactile elements central to many of Isabella’s small-scale sculptural objects would have appealed to the Marchioness and her courtly entourage, thus emphasizing the sensorial phenomenon of art consumption during the Renaissance.

Reimagining the other types of sensory responses an image might evoke challenges the perception that early modern painting becomes static once it has been ripped from its original time and place. Portrait of a Lady at her Toilette (fig. 1) is one such feast for the senses, offering a visual parallel for period engagement with material culture at the court of Fontainebleau. During the sixteenth century, the court of King Henry II of France attracted an international group of court artists and especially Italian painters, who brought with them an interest in the sensual allure of painting. In the developing discourse of Italian painting, images of the nude female body became a metaphor for the beauty of painting itself, which the viewer was invited to experience and even possess in the case of certain elite patrons.

In her analysis of a similar image of a nude woman at her toilette woven into a tapestry, Laura Weigert accounts for the multi-sensory engagement of this iconographic type and demonstrates how “the scene evokes a multiplicity of sensual pleasures that diffuses a single focus on this body.”3 The beholder is encouraged to consider the silken texture of the sitter’s diaphanous negligée and the sound of courtly music playing from the next room in tandem with the surface of the image itself. When ocular-centric modes of viewing are put aside, one is able to conjure the aroma of the fallen rose petals, the cool clink of the string of pearls, and perhaps even smell the drifting scent of incense or the perfume worn by the seated lady. The nude woman’s elongated fingers pinch the gemstone pendant around her neck and delicately hold a jeweled ring; these gestures formally suggest the tactility central to the painting’s appeal. When we intentionally read images through a sensorial lens, we can gain insight into Renaissance life at the court of Fontainebleau. In considering the full range of sensorial stimuli present in a work of art, we are not met with a mirror onto court life but rather an opportunity to imagine the experiences of the period viewer and sitter.

This issue of SEQUITUR expands this line of thinking to consider the allure and agency of works of art through inquiries into the embodied experiences of artists, patrons, beholders, and collectors. Such a reading of Portrait of a Lady at her Toilette exemplifies the generative potential of looking beyond the canvas to consider the multi-sensorial phenomenon of viewing. Materiality, sound, fragrance, and spectacle are evoked by this issue’s authors, culminating in a body of research which reconsiders what might fall under the purview of art historians as scholars primarily concerned with the visual realm.

In this issue, Sunmin Cha explores the profound visual and sensory dimensions of Albert van Ouwater’s The Raising of Lazarus (c. 1460–1475), a rare surviving work by the Haarlem painter. Cha’s analysis reveals how Ouwater’s painting functions as a dual spectacle—while the viewer marvels at the artist’s technical skill and narrative clarity, the figures within the scene themselves witness the miraculous restoration of life likened to the ritual of the Eucharist. Through an examination of an incense burner from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Madison Clyburn investigates the historical significance of scent in the everyday lives of sixteenth-century Paduans. Clyburn reveals how the stimulating, therapeutic effects of scent shaped the sensory fabric of a city bustling with students, pilgrims, disease, and fragrant imports.

Shifting the focus from sensory engagement to timekeeping, Mya Rose Bailey’s research spotlight offers a poignant examination of how clocks and timepieces at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello plantation distorted and shaped the lived experiences of enslaved laborers. Bailey demonstrates how the sense of sound shaped the lives of enslaved people, thereby seeking to shed light on the silenced bodies whose experiences are often obscured within the extensive historical archive.

In her visual essay, Elise Racine explores the dynamic interactions between digital and physical realms. With an emphasis on knowledge-sharing through the lens of sensory interaction, her work—inspired by the materiality of traditional book art in tandem with digitally accessed work—aspires to redefine our engagement with knowledge as an embodied, sensory act.

R.J. Maupin’s thoughtful review of Sensorium: Stories of Glass and Fragrance, curated by Julie Bellemare at the Corning Museum of Glass in Upstate New York, underscores the power of scent in shaping historical narratives. Maupin highlights the immersive approach to the exhibit which invites visitors to smell fragrances infused with spices traded by Dutch merchants, while also encouraging reflection on how sensory engagement influences production processes. Angelina Diamante reviews Conjuring the Spirit World: Art, Magic, and Mediums, a comprehensive five-month-long survey of Spiritualism at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. Considered in this review are the twentieth-century performances of magic and seances, and the ways in which reality and spectacle harmonized with the senses to achieve resolution with contemporary audiences.

Together, these contributions offer a rich exploration of the sensory dimensions of art and history, demonstrating how our engagement with the world around us shapes both perception and artistic creation.

____________________

Rachel Kline is a fifth-year PhD candidate studying the art of the Italian Renaissance. Rachel’s research interests include the representation of the female nude in fifteenth-century Italy and the decoration of Florentine marriage chests. Rachel has held positions at the Penn Museum and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Kaylee Kelley is a doctoral student focusing on art of the early modern period. Her research centers on Renaissance tapestries created across Italy, Flanders, and England with an emphasis on their literary sources and curation. She has held positions at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and the Medici Archive Project.

____________________

1. Michael Baxandall, Painting & Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy (Oxford University Press, 1972), 29–108.

2. Geraldine Johnson, “In the Hand of the Beholder: Isabella d’Este and the Sensual Allure of Sculpture,” in Sense and the Senses in Early Modern Art and Cultural Practice, eds. Alice E. Sanger and Siv Tove Kulbrandstad Walker (Ashgate Press, 2012), 183.

3. Laura Weigert, “Chambres D’amour: Tapestries of Love and the Texturing of Space,” Oxford Art Journal 31, no. 3 (2008): 319.

The Allure of Vision: The Act of Seeing in Albert van Ouwater’s The Raising of Lazarus

by Sunmin Cha

Albert van Ouwater’s The Raising of Lazarus (ca. 1460–1475) is a spectacle in every sense of the word. This rare surviving work by the pioneering Haarlem painter is not only a visual feast for the viewer but also a profound meditation on the act of seeing itself.1 The painting is populated with carefully rendered figures dressed in vibrant, richly detailed attire, their varied poses and expressions drawing the eye across the composition. In the foreground, the viewer encounters the striking figure of Lazarus himself. His pale, lifeless body, now restored to life, is depicted in a vulnerable state of nudity, drawing immediate attention to the miraculous narrative from the Bible. Arriving in Bethany four days after Lazarus had died, Christ met Mary and Martha, Lazarus’s two sisters. After reaffirming the faith of the sisters, Christ called upon the dead man. When he said, “Come forth, Lazarus,” in front of the cave where he had been buried, Lazarus came out with his hands and feet bound in graveclothes.

Previous scholarship refers to Rogier van der Weyden’s The Exhumation of St. Hubert (fig. 2) in the National Gallery, London, as the direct model for Ouwater’s panel, explaining his innovative composition as an imitation of the master.2 However, such an interpretation does not fully account for Ouwater’s distinctive approach. In this essay, I argue that Ouwater deliberately rendered Christ’s miraculous act as a visual spectacle. In doing so, he juxtaposed the biblical narrative with the contemporary liturgical spectacle of the Eucharist.

It should be noted that the moment of Lazarus’s resurrection had rarely been depicted in independent panel paintings in the Netherlands during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Traditionally, this theme was confined to illuminated manuscripts, particularly within the Office of the Dead in Books of Hours, where its placement underscored the narrative’s relevance to prayers for the deceased.3 Ouwater’s—or his patron’s—decision to isolate this moment from its traditional narrative context and depict it as an independent panel painting marks a significant shift. It transforms the scene from a private devotional aid in small-size manuscripts into a striking large-scale visual spectacle.

Moreover, Ouwater’s panel strikingly departs from the biblical description as well as the pictorial tradition.4 He moved the event to the choir of a Romanesque church.5 This indoor setting of the scene contradicts the biblical account of the event, which precisely refers to Lazarus’s tomb as a “cave.”6 To the best of my knowledge, Ouwater’s painting is the only fifteenth-century Netherlandish panel to set the Raising of Lazarus within an architectural interior.7 For instance, two Flemish manuscripts, roughly contemporaneous with Albert van Ouwater, depict the resurrection of Lazarus in a distinctly different manner from Ouwater’s panel. One is found in the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry which was illuminated by the Limbourg brothers between 1411 and 1416 (fig. 3). Another manuscript, known as the Salting Hours, was made in the workshop of Simon Marmion around 1470 (fig. 4). In both manuscripts, the Raising of Lazarus appears in the opening page preceding the Office of the Dead. While architectural elements are present, the open fields, trees, and expansive sky clearly establish the outdoor setting.8

In Ouwater’s panel, the inner space of the Romanesque church is occupied by the biblical figures. The painter clearly separated the spectators into two contrasting groups. To Lazarus’s right stands Christ, who has raised him from the dead with his hand in blessing. Mary kneels at Christ’s side, facing her brother in prayer. Martha—the second sister of Lazarus—and three disciples complete the group of people gathered around Christ. Each of them is depicted in humble gestures of devotion and reverence. In stark contrast, the figures on Lazarus’s left—lavishly dressed Jews—add an element of opulence and skepticism to the scene. Among them, two individuals vividly cover their noses, recoiling from the stench of the decaying body of Lazarus.9 The visceral response not only heightens the realism of the scene but also evokes a multi-sensorial dimension, inviting viewers to imagine themselves present in this miraculous moment.

In the immediate foreground, the protagonist of the narrative, Lazarus, emerges from his grave in a strictly frontal position, directly facing the viewer.10 In the miniature examples, Lazarus is depicted rising out of the grave in an oblique pose as he gazes at Christ (figs. 3 and 4). This is also visible in a later painting by Geertgen tot Sint Jans (ca. 1465–1495), who was a disciple of Ouwater (fig. 5).11 In these instances, the pictorial emphasis is on Christ, not Lazarus. As Lazarus’s body and gaze guide the beholder’s attention to Christ, they emphasize that the miraculous resurrection of the dead was made through the intervention of God. On the contrary, Ouwater put a greater emphasis on Lazarus. In his painting, Christ is relatively invisible compared to Lazarus whose centrality and frontality immediately capture the beholder’s attention.

The unusual prominence given to Lazarus may allude to the Mass.12 Since the earliest days of Christian theology, Lazarus’s resurrection has been understood as a prefiguration of Christ’s own resurrection and, by extension, the Eucharist. Just as Lazarus emerged from his tomb after four days, Christ rose from the dead. During the Mass, this resurrection was symbolically reenacted each time the priest elevated the host above the altar, emphasizing the transformative power of the sacrament.13 Twelfth-century theologian Simon Tournai likened Lazarus’s resurrection to the miraculous transubstantiation at the Eucharist, emphasizing that both events defied natural order through divine intervention.14

Indeed, the prominent place of Peter in Ouwater’s painting alludes to the priestly role in the sacrament of the Eucharist.15 Behind Lazarus stands Peter, who uses an expressive gesture to point out to the Jews the deep meaning of the miracle that is taking place before their eyes. Ouwater has given Peter an unusual position at the very center of the composition. Not only does he conspicuously occupy the middle of the painting, but his wide-open arms also introduce the resurrected Lazarus to the spectators in the painting and to the viewer outside the painting. His significant role in the resurrection of Lazarus is testified neither in the Bible nor in the preceding images.

Behind him, the remaining part of the building is separated by a wall-like structure. Behind this structure, the crowd trying to witness the event is seen through the grate of the window, and these figures form a dynamic, densely packed group. Their presence suggests the widespread fascination and curiosity surrounding Lazarus’s resurrection. Yet these figures are not merely decorative; they become participants in the drama, as they bear witness to the climactic moment of Lazarus’s resurrection.

Compared to the onlookers in The Exhumation who surround the entire ambulatory behind the screen, they occupy only a small part of Ouwater’s painting (figs. 6 and 7). However, the meticulous depiction of their gestures and faces effectively conveys their desire to witness the miraculous event in front of them. Given the approximately nine people tightly squeezed into a small window-like frame, one can almost feel how they push each other to get a better view of the miracle. For instance, one man raises his chin to look beyond another person in front of him, which shows his intense desire to witness the event. Even though Rogier van der Weyden’s panel is much more crowded, the onlookers behind the choir screen do not show any eagerness to see the event happening before them. Their calm and even aloof attitude strikingly differs from the spectators in The Raising of Lazarus who indeed illustrate the dynamic act of seeing.

Together, the figures of Lazarus and Peter, along with the spectators arranged along the vertical centerline of the painting and set within a Romanesque building, visually evoke the ritual practice of the Eucharist as understood in the late medieval period. As Miri Rubin has argued, at the center of the whole religious system of the Late Middle Ages lay a ritual which turned bread into flesh.16 The Eucharist serves as a means for believers to recall Christ’s past sacrifice while making it present and accessible to them. Through this reenactment of the original sacrifice, the ritual renews and imparts grace.17 However, the participation of the laity was limited to viewing the sacrament, as they rarely consumed the Host on days other than Easter.18 Instead, they regularly attended church to witness the Elevation of the consecrated Host.19

The exceptional level of desire to see the resurrection of Lazarus figured in Ouwater’s painting, in fact, parallels contemporary worshippers’ yearning to participate in and see the Elevation of the Eucharist. The Elevation was essentially a moment of the display. Introduced in the twelfth century, the ritual of raising the Host was designed to visually engage the laity and mark the moment of transubstantiation—especially since most worshippers had little understanding of Latin prayers.20 To enhance its visibility, measures were taken such as suspending a brightly colored cloth behind the altar or using candlelight to silhouette the raised Host.21 In fact, according to a fifteenth-century Augustinian monk, some worshippers even called out to the priest, urging him to raise the Host higher.22 To see the Host was the most important element for late medieval devotees during the celebration of the Mass. This was to see the real presence of Christ.

Albert van Ouwater’s The Raising of Lazarus captures a dual spectacle: the viewer outside the painting marvels at Ouwater’s technical mastery and vivid storytelling, while within the painting, the spectators themselves behold the miracle of life restored by Christ. The late medieval viewer of Ouwater’s painting could identify with the onlookers behind the window, who embody the visual experience during the Mass. Indeed, a man clothed in red, looks directly at the viewer and urges us to join him. In this sense, the real spectators and painted spectators converge in Ouwater’s painting. This multi-layered interplay between seeing and being seen transforms the theme of the Raising of Lazarus into a deeply immersive experience, inviting the audience to reflect on their own role as spectators of the miraculous.

____________________

Sunmin Cha is a PhD candidate at Columbia University focusing on the intersections between religious iconography and artistic production in sixteenth-century Haarlem, with a particular emphasis on the Man of Sorrows. She is currently writing her dissertation which examines how artists like Maarten van Heemskerck, Cornelis van Haarlem, and Hendrick Goltzius responded to the religious and political shifts of the time through their paintings.

____________________

1. The attribution of The Raising of Lazarus to Albert van Ouwater (ca. 1415–1475) is largely based on the description of Karel van Mander: “I have seen a grisaille copy of a large, upright painting done by Albert, portraying the Resurrection of Lazarus. The original had been taken to Spain in a tricky way, without any payment having been made, after the siege and surrender of Haarlem. The figure of Lazarus was beautiful for its time, a remarkable nude painting. An architectural detail in this picture was a temple, of which the columns were rather small. On one side, apostles were shown, on the other, Jews. There were pleasing female figures in the picture, too. In the background some people could be noticed looking through a colonnade of the choir. (Daer was vam hem een paslijck groot stuck in de hooghte, waer van ick heb ghesien een ghedootverwede Copie, en was de verweckinghe van Lasarus: het principael werdt nae d’Haerlemsche belegheringhe en overgangh, met ander fraeyicheyt van Const, van den Spaengiaerden bedrieghlijck sonder betalen ghebracht in Spaengien. Den Lasarus was (nae dien tijt) een seer schoon en uytghenomen suyver naeckt, van goeden welstandt. Daer was een schoon Metselrije van eenen Tempel: doch de Colomnen en t’werck wat cleen wesende, op d’een sijde Apostelen, op d’ander sijde Ioden. Daer waren oock eenige aerdighe Vroukens, achter quamen eenighe, die toesaghen door Choor pilaerkens.)” Carel van Mander et al., The Lives of the illustrious Netherlandish and German painters, from the first edition of the Schilder-boeck (1603-1604): preceded by the lineage, circumstances and place of birth, life and works of Karel van Mander, painter and poet and likewise his death and burial, from the second edition of the Schilder-boeck (1616-1618) (Davaco, 1994). 1: fol. 205 v. The original Dutch is cited from James Snyder, “The Early Haarlem School of Painting: I. Ouwater and the Master of the Tiburtine Sibyl,” The Art Bulletin 42, no. 1 (1960): 42.

2. Stephan Kemperdick, “Albert van Ouwater: The Raising of Lazarus,” Oud Holland 123, no. 3/4 (2010): 241–43. Kemperdick convincingly demonstrates that the motif of the onlookers placed behind a grate in the ambulatory, the brightly lit ambulatory itself, and the open grave placed parallel to the picture plane in a tiled floor are noticeable in both paintings. However, his research likewise focuses on creating lineage between the artists. Based on Ouwater’s familiarity with the van der Weyden panel, he assumes the possible training of Ouwater in the southern Netherlands.

3. Kathryn M. Rudy, “A Pilgrim’s Book of Hours: Stockholm Royal Library A233,” Studies in Iconography 21 (2000): 250. Books of Hours were personal prayer books modeled after the breviaries used by monks and religious communities. Typically, Books of Hours included a variety of prayer sequences or offices, such as the Little Office of the Virgin Mary, the Office of the Holy Cross, and the Office of the Holy Spirit. The Office of the Dead was a specific sequence of prayers intended to be recited for the souls of the deceased, particularly aimed at reducing their time in purgatory. It was often visually introduced by scenes of death and resurrection, such as scenes of Hell, Purgatory, and the Raising of Lazarus.

4. Jacqueline E. Jung, “Seeing Through Screens: The Gothic Choir Enclosure as Frame,” in Thresholds of the Sacred: Architectural, Art Historical, Liturgical, and Theological Perspectives on Religious Screens East and West, ed. Sharon E. J. Gerstel (Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection: Harvard University Press, 2006), 185–88. In her research on the Gothic choir screen, Jung specifically points out that the indoor setting of the painting contradicts the biblical description of the tomb of Lazarus. She compares the wall-like structure in Ouwater’s The Raising of Lazarus with the Gothic choir screen, which does not only conceal the sacred event from the laity but also reveals it to them.

5. Kemperdick, “Albert van Ouwater,” 235. Carved reliefs on the Romanesque capitals of the ambulatory depict scenes from the Old Testament—the Flight of Hagar and Ismael, the Sacrifice of Isaac, Moses Before the Burning Bush, and God Giving the Tablets of the Law to Moses. Snyder argues that Ouwater placed the event in the choir of a Romanesque church to show that the Old Testament period is ended by the age of the Messiah. Snyder, “The Early Haarlem School of Painting: I,” 39–55.

6. “Then Jesus, again greatly disturbed, came to the tomb. It was a cave, and a stone was lying against it. Jesus said, ‘Take away the stone.’ Martha, the sister of the dead man, said to him, ‘Lord, already there is a stench because he has been dead four days.’” (John 11: 38–39).

7. Although I have not encountered any other depictions of the Raising of Lazarus set within an architectural interior from any period or region, given the vast scope of surviving visual material, I remain cautious about stating categorically that Ouwater’s panel is entirely unique in this regard.

8. In the miniatures, the architectural elements play only ancillary roles compared to the Romanesque building in Ouwater’s panel that encompasses the entire biblical scene. The destroyed Romanesque building in The Raising of Lazarus from the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry implies the coming of Christ and the transition from Judaism to Christianity. Simon Marmion also depicted architectural detail in the background which looks like the wall of a city or the exterior of a building.

9. This does not imply that the negative depiction of the Jews is the original invention of Ouwater. In fact, the hostile depiction of Jews and negative connotations were highly prevalent in the religious images of northern Europe. However, they usually appear in the Passion cycle, especially as the tormentors of Christ. The scholarly discussion on Jews in premodern European society and their visualization is extensive. See Moshe Lazar, “The Lamb and the Scapegoat: The Dehumanization of the Jews in Medieval Propaganda Imagery,” in Anti-Semitism in Times of Crisis, eds. Sander L. Gilman and Steven T. Katz (New York University Press, 1991), 38–80; Ruth Mellinkoff, Outcasts: Signs of Otherness in Northern European Art of the Late Middle Ages, 2 vols. (University of California Press, 1993); Heinz Schreckenberg, The Jews in Christian Art: An Illustrated History, trans. John Bowden (Continuum, 1996); and Debra Higgs Strickland, Saracens, Demons, & Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art (Princeton University Press, 2003).

10. His frontal view strikingly contrasts with the almost horizontal body of St. Hubert in Rogier van der Weyden’s painting, an alleged source for Ouwater. Without any mediating help, Lazarus stands up. The rigid frontal body of Lazarus and vertical direction recall the body and movement of Christ in his own resurrection.

11. Henry Martin Luttikhuizen, “Late Medieval Piety and Geertgen Tot Sint Jan’s ‘Altarpiece for the Haarlem Jansheren’” (PhD diss., University of Virginia, 1997), 192.

12. As the resurrection of Lazarus prefigures that of Christ, the tomb in Ouwater’s painting also reminds the viewer of Christ’s sarcophagus. Given that the altar was commonly interpreted as Christ’s allegorical tomb since the Carolingian period, the parallel placement of the tomb is significant. Godefridus J. C. Snoek, Medieval Piety from Relics to the Eucharist: A Process of Mutual Interaction (E.J. Brill, 1995), 186–202.

13. Luttikhuizen, “Late Medieval Piety,” 192.

14. Benedicta Ward, Miracles and the Medieval Mind: Theory, Record, and Event, 1000–1215 (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1987), 15.

15. Even though he does not carry his attributes, Peter’s physiognomy is recognizable. By the fifteenth century, St. Peter was commonly portrayed with a distinctive bald patch on the crown of his head. Since the ninth century, only priests were permitted to handle the host, which led to the widespread practice of the priest placing it directly into the worshipper’s mouth. This reinforced the priest’s role as a mediator between the divine and the laity. Luttikhuizen, “Late Medieval Piety,” 196.

16. Miri Rubin, Corpus Christi: The Eucharist in Late Medieval Culture (Cambridge University Press, 1991), 1.

17. Luttikhuizen, “Late Medieval Piety,” 194–5.