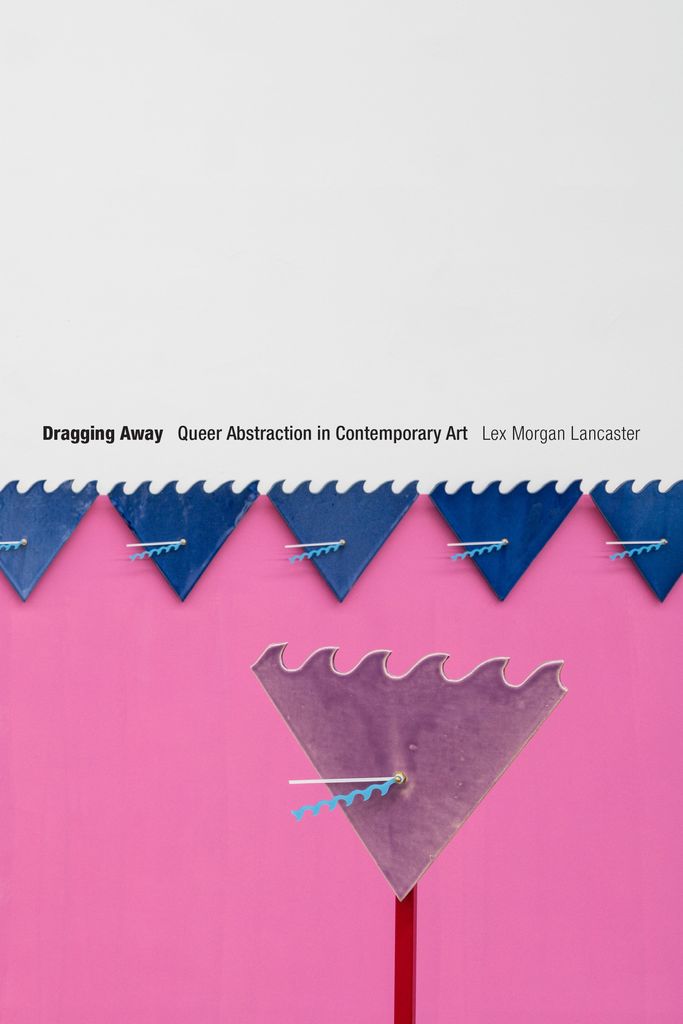

Dragging Away: Queer Abstraction in Contemporary Art

by Shawn Simmons

LEX MORGAN LANCASTER

Dragging Away: Queer Abstraction in Contemporary Art

Durham: Duke University Press, 2022. 208 pp; 35 illust., incl. 16 page color insert

$24.95 paperback

978-1-4780-1867-4

In a review of the Des Moines Art Center’s 2019 exhibition Queer Abstraction, Lex Morgan Lancaster pointed out the difficulty of a central term: “‘queer abstraction’ may seem a contradiction in terms, since direct representation and visibility have been so central to queer politics and the ongoing battle for LGBTQ rights and recognition in the public sphere. We have come to expect a politically viable queer art to include overt imagery of queer bodies, communities, erotics.”1 Despite this apparent contradiction, Lancaster understands queer abstraction as a mode of expression that disrupts representational conventions of gender and sexuality. Encompassing a range of visual practices, queer abstraction can evoke complex and fluid experiences of desire, embodiment, and subjectivity.

Where, then, does queer abstraction find its place in art history? In Dragging Away: Queer Abstraction in Contemporary Art, Lancaster explores this question, offering fresh insights into the transformative power of abstraction to reject normative conceptions of identity, destabilize fixed categories, and reimagine possibilities for self-expression and social critique. Building on the scholarship of queer theorists and art historians alike, Lancaster posits that abstraction is never a neutral gesture. In Lancaster’s compelling analysis, “queering” acts as a “force or vector that works beyond particular bodies” and ultimately allows abstract artists to resist erasure and reject fixed interpretations of identity (14). Throughout the book, “drag” and “dragging” are processes that “exert a destabilizing pull on us as viewers” (3). Drawn from Elizabeth Freeman’s term “temporal drag” and the queer mode of performance, Lancaster’s focus on drag reframes and challenges artistic conventions, ultimately inviting a more reparative reading of abstraction as a tool for queer resistance through its emphasis on materiality over visibility.2

Much of Dragging Away grapples with the ambiguity of the term “queer” itself. The author focuses on each artist’s contribution to gender and sexuality politics through queering. Lancaster’s interdisciplinary approach draws from visual, queer, feminist, Black, and disability studies, demonstrating the emancipatory potential of abstraction to challenge disciplinary boundaries. Constantly questioning the division between formal and social concerns across four thematic chapters, Lancaster examines the ways in which artists manipulate formal elements such as geometry, color, and materiality to disrupt the representational frameworks of queer art and allow for new modes of perception. This nuanced approach explores the intersections of identity, representation, and artistic practice. Lancaster’s use of “queer formalism,” as coined by Jennifer Doyle and David Getsy, emphasizes close visual analysis while considering how gender, sexuality, and desire operate beyond formal depictions.3 Lancaster uses this methodological framework to uncover layers of meaning within artworks that extend beyond their surfaces. Several of the author’s contemporary case studies are placed in contact with canonical twentieth century abstract works in order to examine how these artists have reinterpreted and subverted the exclusionary tendencies of modernism.

In chapter one, Lancaster considers the use of hard-edge geometric forms in contemporary artwork by Nancy Brooks Brody, Every Ocean Hughes, and Ulrike Müller. Placing these examples in opposition to modernist works by Ellsworth Kelly and László Moholy-Nagy, Lancaster reinterprets the hard-edge line as a queer visual tactic, a site of activation that “gives way to a transitory process of edging that unfixes and exceeds containment” (39). This temporal drag extends into the second chapter, “Feeling the Grid,” in which Lancaster juxtaposes Lorna Simpson’s Public Sex series with Agnes Martin’s grid paintings. In Simpson’s photo-based felt installations, the grid acts as a vector for various forms of queer relationality. Lancaster notes how the “queer alchemy” of the grid allows for a certain flexibility, creating a “space for intimacies to exceed bounds of difference, of public and private, of historicizing coordinates of here and now or then and there” (80). In chapter three, Lancaster turns to the significance of vibrant color in work by Linda Besemer, Lynda Benglis, and Carrie Yamaoka, arguing that the queer potential of color appears in these works “as both a material and an optical element that performs affectively rather than representationally” (89). The final chapter examines spatial and material elements of installations by Sheila Pepe, Harmony Hammond, Shinique Smith, and Tiona Nekkia McClodden, arguing that these artists adopt the processes of unraveling, ripping, and cutting to deform and destabilize notions of material coherence. The book concludes with a short epilogue in which Lancaster critically considers the symbolic evolution of the rainbow pride flag since 1978, offering a reflective lens through which to assess the broader implications of queer abstraction explored throughout the text.

While Dragging Away offers noteworthy contributions to several disciplines, Lancaster’s foregrounding in art history holds significant implications for the field. In challenging prevailing narratives that prioritize the depiction of bodies or explicit eroticism in queer art, Lancaster shifts our attention to queering as a strategic method for resisting fixed categories of identity. This approach may interest readers beyond academic circles, attracting anyone interested in contemporary art, queer studies, or cultural theory. Occasionally, the analysis is impeded by the inherent challenges of translating abstract visuals into language; the author reflects on this in the third chapter, noting that the “difficulty of putting our experience of color into words constantly reminds us of the limits of linguistic expression” (89). However, the considerable number of images allows readers to contextualize and engage in their own visual analysis. While the book is scholarly in its theoretical approach and analyses, the extensively illustrated text is accessible and engaging for general readers with an interest in its interdisciplinary material. A timely addition to the broader discourse on the (in)visibility of identity in contemporary art, Dragging Away invites us to reconsider the roles queerness can play in embodiment and representation—and in art at large.

____________________

Shawn C. Simmons is a PhD student in the History of Art and Architecture at the University of Pittsburgh, where he studies queer theory and ecology in American art after 1945.

____________________

1. Lex Morgan Lancaster, “Queer Abstraction,” ASAP/J, July 16, 2019. https://asapjournal.com/review/queer-abstraction-lex-morgan-lancaster/.

2. For further discussion of the term “temporal drag” see Elizabeth Freeman, “Deep Lez: Temporal Drag and the Specters of Feminism,” in Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (Duke University Press, 2010), 59–94.

3. See Jennifer Doyle and David Getsy, “Queer Formalisms: Jennifer Doyle and David Getsy in Conversation,” Art Journal 72 (August 5, 2014): 58–71.