Second Careers: Two Tributaries in African Art

The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH

November 1, 2020–March 14, 2021

by Diane Dias De Fazio

Second Careers: Two Tributaries in African Art connected canonical works from western and central Africa to works from contemporary artists active in Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, and Mozambique, whose use of repurposed materials echoes practices of the past.1 As its title implied, the exhibition introduced dual themes, one that considered the “second careers” of artworks—as both museum objects and foundational inspiration to succeeding generations of artists—and one that demonstrated how contemporary artists give salvaged materials new “lives” as art. The exhibition posed the questions: What will the “second careers” of twenty-first-century African artworks be, and what conversations will they inspire after entering museum collections?

Planned and executed by Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi (now the Steven and Lisa Tananbaum Curator of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, New York), Second Careers examined nine historical African artworks from the collections of the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA), Emory University’s Michael C. Carlos Museum, and the Brooklyn Museum, alongside the art of six contemporary practitioners representing different generations: El Anatsui, Tahir Carl Karmali, Gonçalo Mabunda, Nnenna Okore, Zohra Opoku, and Elias Sime. The ambitious exhibition was further distilled through three “lenses”—memory, materiality, and transformation—which Nzewi attempted to universally apply to all the works in Second Careers.

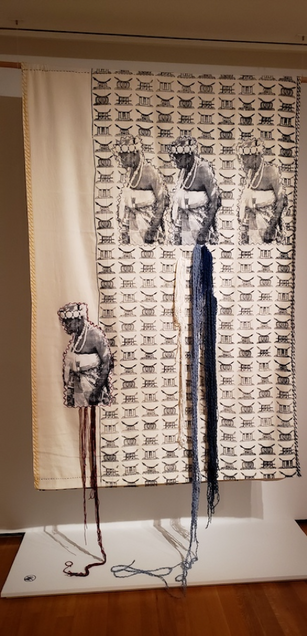

Considering this conceptual framing, and the spatially challenging Julia and Larry Pollock Focus Gallery in which Second Careers was displayed, the exhibition carried substantial thematic and visual demands, with intermittent levels of success.2 Large-scale works by Anatsui, Okore, and Sime dominated two walls. Babanki, Baule, Chokwe, Kuba, Malinke, Songye, and Yoruba cultures were represented through compelling masks, figures, and garments, but offered up without much context to each other (geographically or thematically) and with weak interconnection to the contemporary pieces. Zohra Opoku’s Nana Opoku Gyabbah II, Chidomhene of Asato/Akan was arguably the sole piece capable of being viewed through all three “lenses”: the artist recalled “traditional concepts of the past” through repeated screen-printed symbols and images of her late father in his kente-cloth wrapper (memory lens), chose “materials . . . imbued with meaning” in terms of Ghanaian industry and identity (materiality lens), and transformed her signature medium—textile—in an innovative way, as a personal tribute to her ancestors (transformation lens) (fig. 2).

The same could not be said for all exhibition items, which, cumulatively, created an adverse effect and undermined the premise of the show. The majority of the contemporary works in Second Careers evidenced no direct inspiration from the historical items. The exhibition excelled in its arguments for the “second careers” of museum objects: Most of the historical items were created for and used in spiritual and ceremonial contexts, but, bereft of their intended purposes, play an established role as beautiful artworks. The exhibition was not particularly strengthened by the Ndeemba mask, and the Kuba prestige belt evidenced great craftsmanship, but these and other smaller historical works felt squeezed into the space.

Tahir Carl Karmali’s Jua Kali photo-composite portraits depict Nairobians as cyber-steampunk deities, created to “look as if one adorned themselves with found objects, which somehow work together to make them superhuman”3 (fig. 3). Here again, the connection with historical objects was flimsy: Curatorial perspective viewed the portraits as linear descendants of items like the nearby Songye power figure,4 but Karmali’s own artist’s statement emphasized that his series was “inspired by the informal sector [referred to by the term ‘jua kali,’ Kiswahili for ‘fierce sun’] that breathes character into Nairobi’s economy,” and aimed to change perceptions of Jua Kali workers.

Was the Malinke hunter’s shirt, with its leather pouches filled with Islamic scripts, inspiration to Elias Sime’s Tightrope: Non-Essential Speed (figs. 4, 5)? In gallery labels, Nzewi suggested that Sime’s small plastic telephone wire connectors “recall[ed]” the shirt’s leather pouches, but in the catalogue, the curator acknowledged such a suggestion “may seem a stretch.”5 And, indeed, it did seem a stretch, and the acknowledgement only a hollow justification for a comparison that added little to the visitor’s understanding of either object. Sime’s masterful collage of accumulated electronic materials did not need this linkage to stand on its own: Repurposed materials created an arresting artwork, one that also served as a meditation on environmental waste and the aftereffects of colonialism.

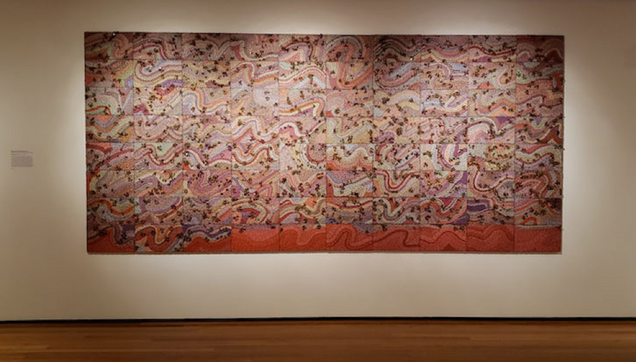

There are two additional instances in which the “tributaries” of the exhibition’s subtitle meet. First, Gonçalo Mabunda’s Harmony Chair (2009), comprised of “decommissioned” weapons and ammunition, is a metaphoric plea for peace; paired with the Babanki prestige chair (1800s), a wooden seat crafted and sold for European export, museumgoers were handed a sobering thought: Where does the “seat” of power lie, in culturally (in)appropriate symbols, or in disarmament and accord (figs. 6, 7)? Then, two large showstopping works together exemplified the multifaceted connections between historical objects and contemporary works. The literal centerpiece of Second Careers, a Yoruba egúngún masquerade dance costume (1920–1948), is a crafted assemblage of polychromatic layers of reused fabric and aluminum (fig. 8). Nearby, Anatsui’s Earth Growing Roots (2007), a shimmering curtain of woven yellow, red, and silver bottle caps, directly echoes the egúngún in repurposed materials, scale, and visual flamboyance (fig. 9). Anatsui has said he “looked at classical or traditional African art and [had] seen how the freedom to work with various materials is possible.” The egúngún, crafted out of three-hundred local and imported textiles, has had a strong “second career” of numerous exhibitions (and inspired unknown generations of artists), but the multicolored costume has also enjoyed the benefit of recent scholarship, which revealed more of the item’s “biography.” Hopefully, future exhibitions—particularly of historical African objects, but for contemporary works, as well—will be emboldened to highlight “the many things an object embodies and the multiple stories it holds.”6

The CMA opened in 1916 and its current incarnation, spatially reimagined by Rafael Viñoly Architects in 2009–14, joins old and new with a spacious light-filled atrium, where special exhibition galleries face the classically inspired original structure. This juxtaposition befits an exhibition like Second Careers, which consciously reckoned with the cultural history of institutional African art connoisseurship and proffered a vision of future museum collections in which institutions can re-evaluate their historical items and present contemporary works in the same spaces as canonical objects. This pivot, increasingly popular in museums, signals a new way of encouraging the public to understand art: on a global timeline that simultaneously looks backward and forward with a critical eye. Whether institutions that take this approach—the CMA and Museum of Modern Art are but two examples—continue in this vein, remains to be seen.

____________________

Diane Dias De Fazio

Diane Dias De Fazio is a first-year Master of Arts candidate in art history at Kent State University. Her research and practice centers on artist’s books, alternative/underground press, and work by women and BIPOC printers in Ohio and Western Pennsylvania. She holds masters’ degrees from Columbia University and Pratt Institute.

____________________

Footnotes

1. Unless otherwise noted, quotations in this review come from exhibition label text.

2. The gallery was designed for exhibitions of one item, and linked to the adjacent interactive Gallery One. Under COVID-19 protocols, Gallery One was closed indefinitely, and maximum occupancy in the Focus Gallery was eight people.

3. Tahir Carl Karmali, “Jua Kali,” accessed April 2020, http://tahirk.com/jua-kali/.

4. The pairing appears as the cover image for the Second Careers catalogue.

5. Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi, Second Careers: Two Tributaries in African Art (Cleveland, OH: Yale University Press, 2019), 46–7.

6. Nzewi, Second Careers, 27.