Editors’ Introduction

by Phillippa Pitts

I have always been fascinated by our species’ inclination to find patterns in randomness. There appears to be an indefatigable human capacity to create order from the chaos of lived experience. Across science, religion, civics, and society, we create rules: rules for living, rules for doing, rules for nature, even rules for systems so enormous that they defy our understanding and so unpredictable that they should suggest anything but order. Nevertheless, we persist.

As scholars of art and visual culture, we have a particular perspective on this kind of behavior. From the visualization of Darwin’s evolutionary trees to Barr’s genealogical maps of modern art, the visual field is not a passive reflection of these orderings: It is an active site of inquiry, argumentation, and knowledge production. Seemingly small choices in color, line, shape, and composition exert outsize influence. They also wield the power to disguise individual choice or creation under a veneer of inevitability or neutral factuality.

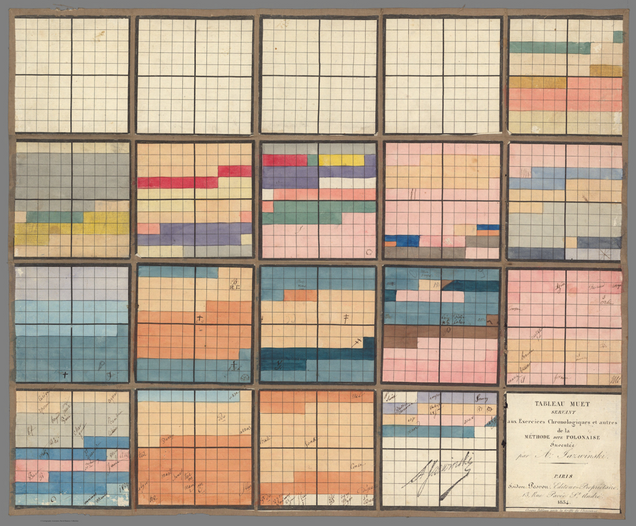

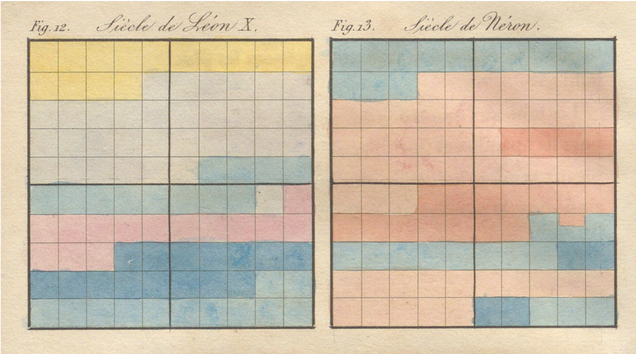

The opening image for this essay is a chronograph, an attempt to diagram or map time in pursuit of a perfect, singular, comprehensive view of history. For centuries, artists and designers have tackled this impossible challenge by drawing on astronomy, numismatics, and innovative cartography for methods by which to compress vast volumes of data into still-legible charts and tables. Denotative text is of limited use. It is connotative visuality which further condenses the information: Flags, shields, and insignia can serve as shorthand for nations and dynasties, while looming storm clouds, bright sunbursts, and invocations of classical architecture add layers of associative meaning.1 This particular chronograph, developed by nineteenth-century Polish designer and educator Antoni Jażwiński, is perhaps the most distilled solution that I have encountered. A mnemonic system, Jażwiński’s Méthode polonaise promises that the complexities of centuries can be refined into colors, lines, squares, and just a few marks (fig. 2). Neatly arranged into a diagram that can be diligently committed to memory, the twists and turns of battles and revolutions are rendered as panes of pure gentle color, quietly plotted as coordinates in a matrix, subsumed back into the orderly progress of history.

There is a wonderful resonance between Jażwiński’s chronographs and a wide range of artistic production, despite the anachronism of such comparisons. They recall Piet Mondrian’s early checkerboards and Robert Delaunay’s simultaneity. There is something reminiscent of process art here: They evoke the repetitive, cataloguing handwork of Hanne Darboven or Agnes Martin. There appears to be a common calm, comfort, catharsis, or salvation promised by the embrace of rule, order, and logic.

It is clear that order, chaos, and visuality have long been profoundly intertwined. In this issue of SEQUITUR, we invited perspectives on one aspect of this complex relationship: deregulation. As historians, we know that deregulation can be both an emancipatory act and a form of abandonment. In some instances, the lifting of rules brings liberation, joy, or renewal. It can surface histories, stories, and truths which have been suppressed by social and didactic frameworks. At other times, deregulation only provokes paralysis or exacerbates inequities of power: unleashing laissez-faire ideologies to wreak havoc on peoples, places, and environments. As an art, architecture, and visual-culture journal, we asked authors to tell us about how the activist and the aesthetic, the political and the personal, the art world and the everyday are all inextricably linked. In short, we asked for authors to engage with deregulation in the broadest of senses: examining the manner in which rules like these are constructed, how they are broken, and what happens when they are lifted.

Interestingly, our prompt produced few answers to the questions we posed. Instead, we received only more questions in return. Where our calls for papers usually prompt a flood of proposals for feature essays and completed projects, this spring we primarily received a flurry of suggestions for interviews, exhibition reviews, and spotlights on works in progress. Although the selected essays span continents and centuries, the throughline which brings this issue together is a sense of dialogue, debate, and unfinished conversation. These processes of inquiry and exploration, beautifully presented by nine authors, form the heart of this publication.

Emily Beaulieu opens our issue with a feature essay that recovers traces of cultural exchange and Indigenous survivance in New Spain. Taking an extraordinary sixteenth-century featherwork composition as her case study, Beaulieu locates not only Nahua technique but Indigenous patterns of thinking and approaches to spatial visualization within an image of St. Gregory. Beaulieu does not describe one message hidden behind another, but proposes the beginning of a new language reflective of a new set of beliefs, neither Spanish nor Nahua. There’s a productive synergy between this piece and Marina Wells’s discussion of Writing the Future, a recent Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston, exhibition profiling twentieth-century New York artist Jean-Michel Basquiat. As Wells describes, Basquiat is also a part of a movement to produce a new language reflective of a new type of lived experience. Contextualized among his friends and contemporaries, Basquiat’s work is framed as part of an effort by Black creators to reshape and reimagine Black futures in irreverently synergistic, cannibalistic, and liberatory forms. Yet Wells also makes a pointed critique, noting the ways in which the conversation begun by the MFA is incomplete, still struggling to reconcile with systemic racism, police violence, the criminalization of addiction, and the AIDS crisis, despite the institution’s efforts to bring many voices to the table. Diane Dias De Fazio’s review of Second Careers: Tributaries in African Art picks up on these questions of museum practice. The exhibition explores how the gallery context has, and continues to, facilitate the transformation of objects from the African continent: from everyday materials into valuable singular objects, from functional creations to exhibits of fine art. De Fazio’s analysis highlights the exhibition’s forwards-backwards orientation, embodying the curator Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi’s goal of honoring “the many things an object embodies and the multiple stories it holds” in contemporary and historical examples alike. Yet De Fazio’s review does not merely report on the installation: It enters into a dialogue with this ongoing shift in curatorial practice, pointing to the work still to be done in this area.

Continuing this theme, Stephen Rosser’s research spotlight also invites us into a work in progress, drawing our attention to the connections—real and perceived—between the deregulation of global financial markets and the rise of modern architecture. The two, he explains, have physically and conceptually shaped the City of London in contentious and controversial since the financial “Big Bang” of 1986. By mining the accounts of contemporary commentators and city historians, Rosser’s project shines a new light on how four well known architectural projects were adopted into public and political imaginaries as both reflective and constitutive of this changing Britain. The themes which Rosser introduces—association, memory, and symbolism—are picked up in Gabrielle Tillenberg’s interview with Puerto Rican-born multimedia artist Eric Rivera Barbeito. In their conversation, Tillenberg draws out how Barbeito’s work responds to the island’s own Big Bang, Hurricane Maria, a cataclysmic event which generated a new reality for the island. Barbeito’s work makes present the disastrous human and environmental consequences of neocolonial deregulation in the form of poignant, multivalent objects: a miniature shipping container, a delicate box roofed with tarp, a toy tank flying the Puerto Rican flag. The themes of neocolonial extraction, disaster capitalism, and the nightmare of manifest destiny run amok appear again in Morgan J. Brittain’s conversation with Drew Etienne, a multimedia artist whose found-object installations intervene in the cycle of conquest, extraction, consumption, and disposal. From materials destined for the dumpster, Etienne produces “technofossils” of a degraded post-human landscape. He mixes and distills inks from plants in his Iowa City environs. He seizes forms and images from the Western canon to remake into new compositions that serve both as ominous portents of the future and personal rejections of extractive art-making practices. This consideration of making and materials circles back to the issues raised by each and every author, whether they engaged with sleek steel-and-glass facades or “aerosol expressionism,” sixteenth-century featherwork or found-object assemblages.

The diversity of perspectives found within this publication are mirrored by those described in the last essay of this issue: a summary of this year’s graduate symposium, co-organized by Jillianne Laceste and myself. As is our tradition, SEQUITUR’s spring theme was selected to complement our symposium’s topic: “Crowd Control.” This year’s event met the limitations of a pandemic by leaning into the affordances of the virtual format, welcoming presenters and participants alike from across the globe. A summary of the seven graduate papers presented, as well as the engaging keynote address from Dr. Paul Farber, concludes this issue.

The themes of “Crowd Control” and “Deregulation” were both inspired by the instability which presently surrounds us all. A slew of unprecedented events prompted a succession of unforeseeable responses. Novel constraints tightened their grips, while familiar rules disappeared without a trace. Resistance to lethal injustices, new and old, reached a searing fever pitch. Long-held patterns have been swept away, leaving us in the midst of a new world disorder. From within this chaos, it was reassuring to see examples of emancipatory thinking, past and present. It was a comfort to hear from artists and scholars at work on new solutions. It was a joy to be in dialogue with peers: distanced, but by no means divided.

____________________

Phillippa Pitts

Phillippa Pitts is a PhD candidate and Horowitz Foundation Fellow for American Art at Boston University. Her research explores the ways in which visual rhetorics around expansion, immigration, and Indigeneity have shaped American culture from the long nineteenth century to the present. Phillippa’s work has been generously supported by the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, the Kress Foundation, the Center for American Art, and the University of Michigan.

____________________

Footnotes

1. For more, see Daniel Rosenberg and Antony Grafton, Cartographies of Time (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996), particularly chapters 4 and 6, “A New Chart of History,” and “A Tinkerer’s Art.”