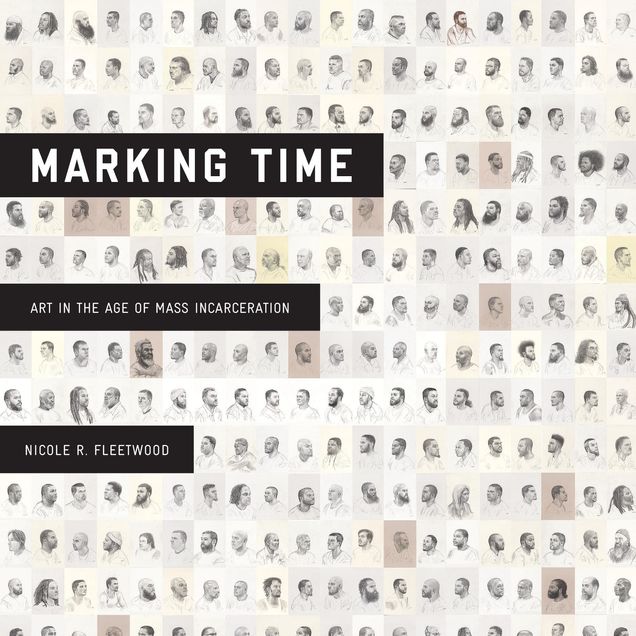

Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration

Nicole R. Fleetwood

Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020. 352 pp.; 95 color ills.

$39.95

9780674919228

by Michael Rangel

Mass incarceration impacts the lives of Black and Brown communities across the United States at disproportionate and irregular rates. Rarely are those affected given the space or time to tell their stories in relational, exploratory, and creative ways. Nicole Fleetwood’s book, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, is based on extensive research and interviews with currently and formerly incarcerated artists and their loved ones, as well as activists and prison staff. It is also drawn from her own family experiences with the penal system, a system that largely imprisons marginalized people. This important text explores the radical potentiality of creating art in insufferable conditions and uncovers the art-making possibilities, imaginaries, and humanity of these incarcerated artists. As a curator, writer, and professor of American studies and art history at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, Fleetwood contests the dominant narrative around aesthetics and the visual representation of those imprisoned. Throughout Marking Time, art serves as a radical practice of freedom and justice within the carceral state.

With more than two million people currently imprisoned in the United States, art practices in prisons exist through complexities of deprivation, abuse, and survival. Fleetwood discusses how the culture and robust nature of art-making inside US prisons can very much act as a means of resisting the isolation, degradation, and dehumanization produced by prison settings. In describing incarcerated artists’ practices and methods, Fleetwood defines “carceral aesthetics” as the visual production of art that emerges from the conditions of the carceral state. It is a way of envisioning and crafting art that reflects the inhumanity of imprisonment. Under conditions of relational practices and “un/freedom,” this carceral aesthetic involves three concepts that Fleetwood explores throughout the book: “penal time,” “penal space,” and “penal matter.” These terms are used to frame how incarceration influences the materials, production, and processes deployed to make art. Within carceral aesthetics, artworks are formations of freedom and unfreedom created to serve as sites for imagination and temporal extraction from regulation, while providing viewers with insights into captivity.

In particular, Mark Loughney’s series Pyrrhic Defeat: A Visual Study of Mass Incarceration (2014), comprised of nearly five hundred pencil-on-paper portraits, and Tameca Cole’s Locked in a Dark Calm (2016), a composite portrait of graphite and collages, visualize the art practices and methods used to survive the constraints of penal time and space, while using penal subject matter. Fleetwood reflects on her own experiences of visits to her cousins while they were serving time in prison and provides her own family’s portraits within the text. Fleetwood, Loughney, and Cole’s portraits embody the connections that occur under unimaginable conditions and envision an archive of carcerality that resists the exploitation and dehumanization of those imprisoned.

Art made in prisons reimagines new aesthetic possibilities and restores what it means to be human. Marking Time is a transformative publication that considers the implications of incarceration and the carceral state. But the power here lies in the possibilities of freedom, justice, and life through the creation of each of these artists’ works.

____________________

Michael Rangel

Michael Rangel is a social worker, scholar, and writer in Chicago, Illinois. He holds a M.S.W. in Social Work from Loyola University Chicago and M.A. in Critical Ethnic Studies from DePaul University. His research focuses on the intersections of race, sexuality, performance, carcerality, and queer/trans identities.

____________________