The Fight for Fair Elections

Don Calloway, founder of the National Voter Protection Action Fund, combats voter suppression at the polls and through policy.

The Fight for Fair Elections

Don Calloway, founder of the National Voter Protection Action Fund, combats voter suppression at the polls and through policy.

At any other time, Don Calloway (’05) would spend the months before a national election traveling around the country reviewing voter protection plans with grassroots organizations, ACLU chapter directors, community groups, and others.

“What is [this plan] trying to do? How is this going to help? How does this work with local election rules in Milwaukee, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, or Atlanta?” he asks. “And what can we do to make sure this plan is as effective as possible, and that people have access to the franchise?”

The COVID-19 pandemic has altered his schedule somewhat, but as founder of the National Voter Protection Action Fund (NVPAF), a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization that works at the state and local level to combat voter suppression and expand access to the ballot box, Calloway still has plenty to do.

Twofold Strategy for Voter Protection

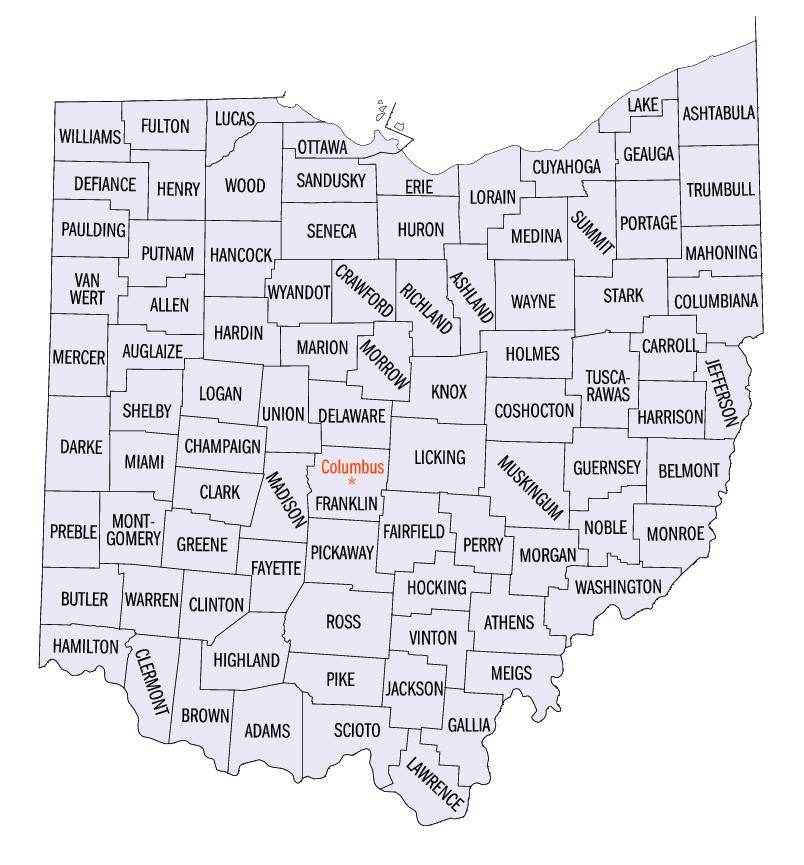

Founded in 2018, the NVPAF’s strategy is twofold: In election years, they work with established organizations as well as grassroots groups planning voter protection activities. They target states with a history of voter suppression and with upcoming contested elections that may trigger suppression activity. For the 2020 election cycle, the organization has homed in on Georgia, Missouri, and Wisconsin. They consult on voter protection plans and offer grants fueled by microfunding campaigns.

“If folks are organizing rides to the polls, training poll watchers, or even buying snacks for people who are standing in line for four or five hours waiting to vote, we are with them and want to give these people grants,” he says. “Anything that’s going on to tear down barriers to vote.”

While changes to voting procedures—many implemented in the name of public health (sometimes with dubious justifications and inequitable consequences)—have prompted hundreds of lawsuits across the country, that advocacy, which plays out through federal courts, is beyond the scope of the NVPAF. “We are funding election protection plans and working on model bills for state voting rights policy,” Calloway says. “There are other organizations, the Lawyers Committee on Civil Rights and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, that are great at that, and we leave it to them.”

In off-cycle years, Calloway works with state legislatures, city and county councils, and third-party organizations to promote voter protection policies that will expand or create early voting periods, defeat voter ID requirements, declare Election Day a holiday, and implement county-wide balloting initiatives so residents can vote at any polling place in their area.

“That policy is where a lot of the voter protection and anti-suppression work happens.” he says. “In the run up to an election, you see a lot of folks are paying more attention to voter suppression and asking how to fight it. Well, that battle is won or lost in the two years preceding an election, because suppression is baked into the process by policy.”

A key to expanding access, Calloway notes, is to make Election Day a paid day off. If the mayor of a city declares Election Day a holiday for its 20,000 employees and also partners with private-sector employers to persuade them to do the same, it gives those people a guaranteed window in which they can cast their ballot without the risk of missing work.

“If you are an hourly wage worker, or if you do not have sufficient paid time off, then having to appear at your specific polling place between 7am and 6pm is akin to a poll tax, because it costs you money to be able to vote,” he says. “And a lot of people make the decision that it’s just not worth it for them.”

Beyond the single day off, Calloway promotes expanded early voting periods to give people more opportunities to participate in elections.

“We should not be talking about Election Day; we should be talking about an election week or even an election period that culminates in Election Day,” he says. “There’s no evidentiary basis to suggest that early voting creates an opportunity for more fraud.”

An Early Pull to Public Service

Growing up near St. Louis, Missouri, Calloway felt a pull toward public service and advocacy early in his career. After three years in a big law practice following his graduation from BU Law, he won a seat in the Missouri House of Representatives. “In the communities I lived in, in the barber shops and the churches, I saw that I was the only lawyer that these people knew or had access to. And I felt like I should be using my time to support the communities I was from,” he says.

When his term was up, Calloway ran for a state senate seat, but lost that race. Wanting to stay in government and political advocacy, he joined the public affairs practice at Anheuser Busch—his “hometown mom-and-pop brewery”—working at first on the state and local level before moving to Washington, DC to work nationally. The position gave him “a foundation in advocacy” and taught him the legislative process on the state and federal level, but he felt pulled back to serve the “greater good.”

“I distinctly remember, in August 2014, I was having a great time in DC, when my high school classmate, Lezley McSpadden, sent me a message on a Saturday afternoon,” he says. “It was one of those instances where I was the only lawyer she knew. She sent me a note and said, ‘Look at what the police have done to my son.’ I’m from a somewhat sleepy, predominantly African American hamlet of St. Louis called Ferguson and Lezley McSpadden’s son was Michael Brown.

“I watched from 2,000 miles away while this pivotal moment—not only for my neighborhood, but for the world—happened,” he says. “Had I won that state senate race, I would certainly have been on the ground, in the middle of it all.”

Wanting to help his hometown through that difficult time, Calloway spent the next two years advising federal stakeholders, law enforcement stakeholders, the Department of Justice, and people on the ground in St. Louis. He became a bridge between investigatory authorities in Washington, DC, the corporate community that wanted to be involved and understand the moment, and the activist community—the clergy and people who wanted to be part of the solution in St. Louis.

Out of that work grew his own public advocacy firm, Pine Street Strategies, which launched in 2016 with the mission of guiding organizational strategy and American policy toward equity. The firm serves corporate clients, like Anheuser Busch, that seek to understand how they can be better corporate citizens while still achieving their business goals, as well as nonprofits like the Environmental Defense Fund, Campaign Zero, and the NAACP.

In building up that practice, he and his team began seeing the “uniform and nationwide” barriers that prevent people from voting. He decided to launch the National Voter Protection Action Fund.

If folks are organizing rides to the polls, training poll watchers, or even buying snacks for people who are standing in line for four or five hours waiting to vote, we are with them … Anything that’s going on to tear down barriers to vote.

Voter Protection and the Presidential Election

As the novel coronavirus spread in the spring, many states holding primaries were unprepared for the increase in requests for vote-by-mail (also known as absentee) ballots, and many ballots either did not arrive in voters’ homes in time to be mailed back and counted or did not arrive at all. States like Wisconsin and Georgia saw hours-long lines at polling places; Ohio rescheduled its primary at the last minute, creating confusion and likely depressing voter turnout.

As the summer, and the pandemic, wore on, states with later primaries sought to make last-minute changes to voting procedures in order to safeguard public health by extending registration deadlines and expanding early voting. Many states are encouraging voters to mail in their ballots, despite sustained—and unfounded—warnings from the president that voting by mail leads to election fraud. In August, the president suggested he might withhold Postal Service funding, which, paired with operational changes that exacerbated mail delays over the summer, prompted congressional hearings and a federal ruling blocking any further changes in process until after the November general election.

Others states have closed polling places and eliminated ballot drop-offs. These practices, which disproportionately impact Black voters, young and elderly voters, and voters with disabilities, may be positioned as responses to the coronavirus pandemic, but, Calloway notes, they are not new.

“The coronavirus presents us all with an extraordinary set of challenges that we could not have been prepared for, on a very practical level—didn’t budget for, don’t have plans for, don’t know how to address—and that is without tampering with the Postal Service,” Calloway says. But from the last presidential election to today, Calloway stresses that no federal policy has changed that would have strengthened voter protections. (The Senate has failed to bring to a vote the December 2019 bill passed by the House of Representatives that would have reinstated the requirement—stripped from the Voting Rights Act of 1965 in Shelby v. Holder (2013)—that states with a history of voter suppression must notify Congress before changing their voting rules.)

Faced with the lack of federal voter protection rules, Calloway and the NVPAF continue to work state by state with activists and organizers to get people to the polls and to focus attention during off-cycle years on local policies that will expand the franchise.

“There is a defined playbook for voter suppression. But there’s also a defined playbook for voter protection. It’s just that we as individuals tend to not focus on the policy during the off years, and that’s where the game is won or lost,” he says. “The war is won in peacetime.”