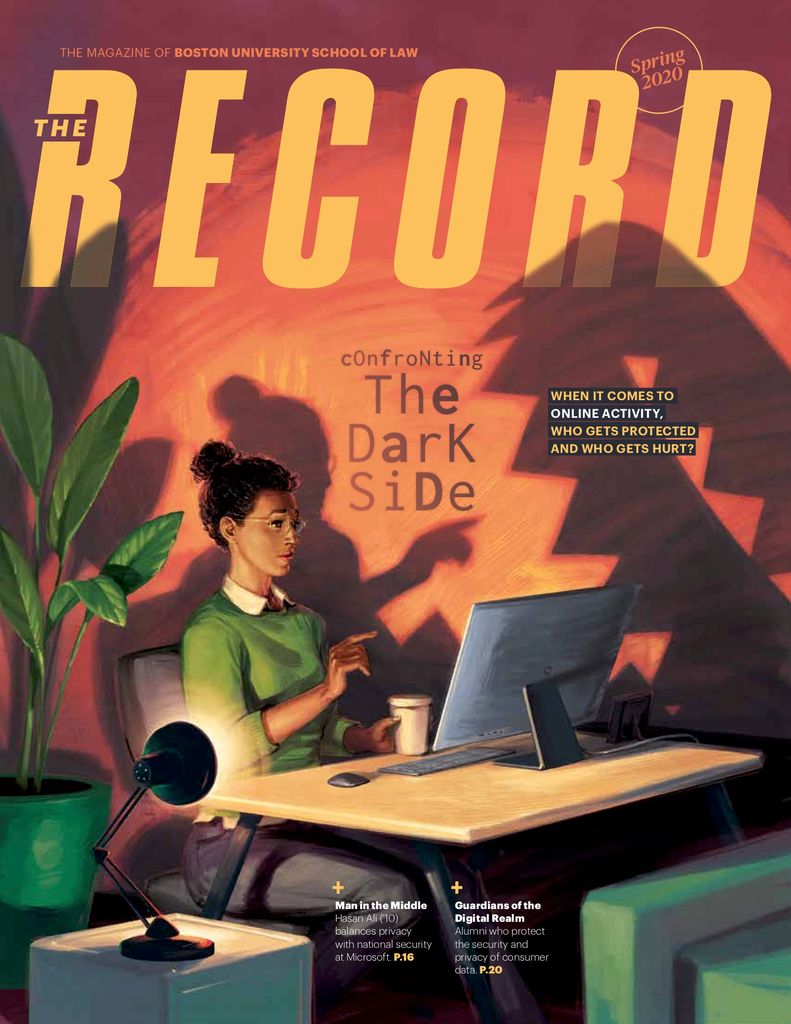

Guardians of the Digital Realm

Temitope Akinyemi (LLM’97) and Sarah Saucedo (’06) take seriously the privacy and security of consumer data.

Guardians of the Digital Realm

Temitope Akinyemi (LLM’97) and Sarah Saucedo (’06) take seriously the privacy and security of consumer data.

Businesses and government agencies today gather and store vast amounts of personal and other data. Schools keep records of our children’s names, addresses, race, birthdays, attendance, grades, test scores, disabilities, why they’ve been disciplined, when they’ve visited the school nurse or psychologist, and whether they qualify for free lunch. Technology companies can harness anonymized and aggregated data to understand sales patterns. Such data can be used to inform urban planning, guide teachers as they prepare lesson plans, and help school districts identify and correct inequities. If this data is used unethically or falls into the wrong hands, however, it could be used to exploit, manipulate, embarrass, or discriminate against us.

As companies and agencies begin to recognize the power of the sensitive data they hold, many of them are taking seriously the privacy and security of that data—some with the help of BU Law alumni, including Temitope Akinyemi (LLM in Banking & Financial Law’97), chief privacy officer for the New York State Education Department, and Sarah Saucedo (’06), senior counsel for privacy and data protection at MasterCard.

As part of a global team led by MasterCard’s chief privacy officer, Saucedo manages the company’s privacy and data-protection programs in Latin America and the Caribbean. MasterCard’s primary business is processing payment transactions (more than 73 billion of them a year), so the company handles vast amounts of transaction data, which includes card account numbers and the place, time, and amount of purchases.

As a major employer, MasterCard also keeps information about salaries, benefits, performance reviews, usage of company computers, phones, and security badges, etc., for more than 13,000 employees around the globe. Saucedo’s job is to make sure the company gathers, stores, and uses such data in compliance with local privacy laws and MasterCard’s internal ethical standards and data responsibility principles. That includes enacting strict privacy practices and ensuring data is used thoughtfully, to make people’s lives easier and richer and to minimize biases, inaccuracies, and unintended consequences.

Recently, she has focused on preparing MasterCard to comply with Brazil’s new General Data Protection Law before it takes effect in August 2020. The law, which is similar to the European Union’s 2016 General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), establishes detailed rules for the collection, use, processing, and storage of Brazilians’ personal data.

“Like the GDPR before it, we’ve embraced Brazil’s new privacy law as an opportunity to advance responsible innovation. As soon as Brazil’s Congress passed that law, we immediately analyzed it against tools and controls we already have in our program and determined which business lines and functions would be impacted,” Saucedo says. Last year, Saucedo spent weeks in the São Paulo office reviewing and mapping all of MasterCard’s data-processing activities in Brazil. Using that map, she and colleagues identified compliance needs and the actions required to address them—including revising contracts with vendors, rewriting privacy notices, and updating products to collect additional or refreshed user consent. Under the new law, citizens have a right to access their data, so Saucedo has been working to ensure all data relevant to individuals in Brazil is available through an online portal MasterCard developed as part of its implementation of the EU GDPR.

At the New York State Education Department, Akinyemi oversees data governance and privacy and also data security for the entire education department, which encompasses 732 school districts, adult vocational training programs, and licensing for professions ranging from teaching to podiatry, as well as the state museum, archives, and library.

She’s tasked with ensuring the education department complies with federal privacy laws and with the state’s student data privacy and security law (Education Law §2-d). Passed in 2014, the law mandated the State Education Department hire a chief privacy officer, and Akinyemi—a technology lawyer with previous experience in the state’s Office of Information Technology Services—is the first person to hold the position.

The law also requires the department establish minimum standards for data privacy and security for all the state’s educational agencies. After considerable research, Akinyemi has recommended adopting a set of security guidelines developed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, and she’s eager to see the framework implemented uniformly across the state. “We talk about equity a lot in education,” she says, “which means that whether you live in Harlem or Brooklyn or Queens, you should have access to the same educational opportunities. I believe there should be equity when it comes to data privacy and security as well.” Every student’s data is worthy of protection, she says, regardless of their location or socioeconomic status.

Education Law §2-d directs the education department to “promote the least intrusive data collection policies practicable” and minimize the collection and transmission of personally identifiable information. In the past, says Akinyemi, educational agencies tended to collect more data on students than they truly needed, thinking it was always better to have more information than less. “We’re changing that mentality,” she says. “Now, with the focus on data privacy and security, we add a level of analysis: How does collecting this data benefit the educational agency? How does it benefit the students? And how do we balance out protecting the data with its use?” When the Lockport City School District recently proposed installing a facial-recognition security system in its school buildings, for example, Akinyemi determined the plan was out of balance—that the risks to student privacy outweighed potential benefits—and she insisted that no students’ faces be included in the system’s database.

In addition to implementing current laws and regulations, Akinyemi is tasked with recommending and drafting new rules and procedures. In January 2020, New York adopted new regulations for strengthening data privacy and security in state educational agencies, which she was instrumental in writing. One of the new regulations requires each educational agency to designate a “Data Protection Officer” whom Akinyemi can train to serve as the point of contact for data security and privacy for that agency. In school districts, Akinyemi envisions this data protection officer helping teachers vet new technologies—helping them, for example, avoid classroom apps that are free for students to use but come with hidden privacy costs.

Sometimes a child’s first device is one they got from the school, and so I think we need to address privacy and security from a perspective of the students as well.

Similarly, Saucedo monitors—and sometimes weighs in on—new privacy and data-protection laws and regulations that could affect MasterCard. “In this region, there’s a new proposed bill to look at literally every day,” she says, and she often meets with her government-relations colleagues or with lawmakers and regulators themselves, sharing her expertise and helping to ensure new rules will be practical to implement. She also participates in meetings and workshops designed to bring industry and regulators together. In February 2019, for example, she traveled to Chile to speak about data protection and innovation at a work-shop for Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) data-protection regulators.

Sharing that expertise is crucial, as end-user education and training are key to the successful implementation of data-privacy standards, especially at large companies and government agencies.

At MasterCard, all employees receive annual training in privacy and data protection, and Saucedo helps make regular updates to the company-wide training material. In her region, she conducts targeted privacy-by-design training sessions for new employees and for specific departments, from human resources to marketing to product development. She also meets regularly with colleagues in MasterCard’s business units to guide them as they’re creating products and services, ensuring privacy principles and controls are not an afterthought but are incorporated into products from the beginning.

Akinyemi has begun requiring all educational agencies to provide annual data-privacy and security training to employees with access to personally identifiable information. The need for this training has become clear, as more than a dozen New York school districts have recently been victims of malware attacks. “Our investigations show that most of the incidents have come through someone clicking on a link in an innocent-looking email,” Akinyemi says, so training staff to recognize phishing attempts is critical, as is training IT staff to back up data frequently.

As “integration” and “interoperability” gain popularity, Akinyemi often reminds her colleagues that siloed data systems have their virtues. “We don’t have to connect these systems just because it’s convenient,” she says. “Concentration of data in one place is a concentration of power.” Another concept she’s introduced is the data life cycle: “At the beginning, when we collect the data, that’s when we should determine how long we need to keep it and put in a plan for expunging it,” she says, “because most of the time, we don’t need to keep that data forever.”

Akinyemi also hopes to find funding to develop a privacy and data-security curriculum for New York students. “Schools are handing kids iPads and Surfaces and Chromebooks,” she says. “Sometimes a child’s first device is one they got from the school, and so I think we need to address privacy and security from a perspective of the students as well.”

People often tell Saucedo they aren’t worried about the privacy of their data because they have nothing to hide. “I don’t have anything to hide either,” she says, “but that’s not the point.” Fundamentally, we safeguard personal data, she says, because we believe it’s the right thing to do. Akinyemi adds that, as consumers, it’s important to understand that our data is incredibly valuable to marketers who use it to sway our opinions and our purchases. And those who work with children and their data should be especially vigilant. “They do not have the life experience that makes them naturally wary,” she says, “so we have to be wary for them.”