Can the Constitution Resolve Culture Wars?

Professor Jim Fleming on how substantive due process has evolved our rights.

Can the Constitution Resolve Culture Wars?

How substantive due process has evolved our rights.

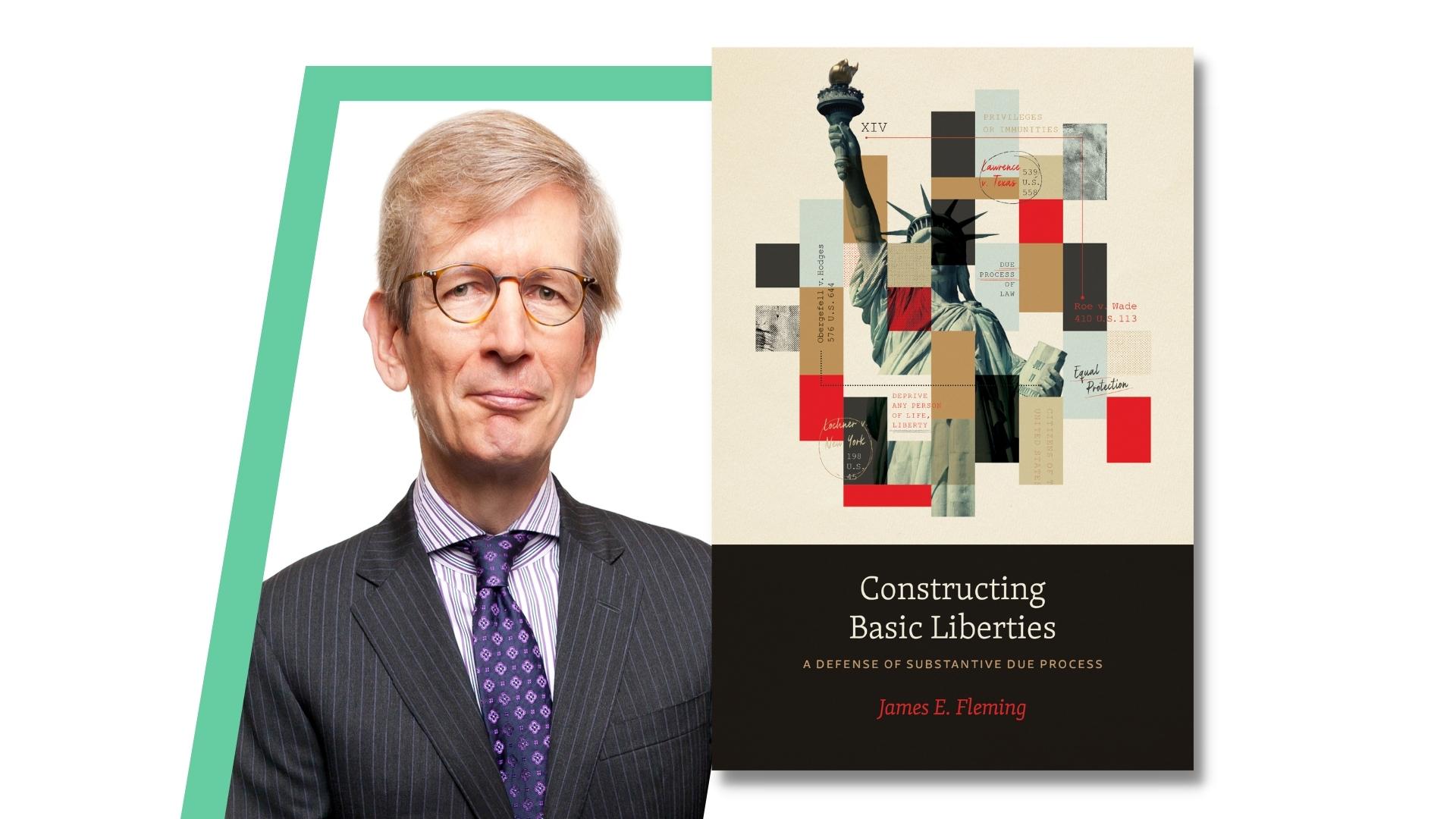

The Record spoke with BU Law Professor James Fleming about his recently published book, Constructing Basic Liberties: A Defense of the Substantive Due Process, which argues the doctrine fulfills constitutional commitments to protect ordered liberty.

Listen to an unabridged version of the interview:

Q&A

James Fleming

The Record: Could you start by defining what substantive due process is?

It is the practice of protecting substantive liberties such as privacy and autonomy under the Due Process Clauses of the US Constitution. Over the last century, and in particular since 1937, the Supreme Court has protected the following basic liberties through this practice: liberty of conscience and freedom of thought, freedom of expressive association and intimate association, the right to live with one’s family, the right to travel or relocate, the right to marry, the right to decide whether to bear or beget children, the right to direct the education and rearing of children, and the right to bodily integrity, including the right to refuse unwanted medical treatment.

The Record: How did your research for your book first start?

For many years, I’ve been thinking about culture war controversies over law and morality and teaching a seminar in jurisprudence focused on such controversies. Every few years, I reconceive the seminar to bring it into line with newer, especially pressing issues. Teaching it turns the writing of a book into a dialogue with the students and thinking through arguments and seeing objections.

This book, in the particular doctrinal setting of culture war controversies over substantive due process, continues the debates from my last book, Fidelity to Our Imperfect Constitution. That book focused on battles over two competing approaches to constitutional interpretation, originalism and moral readings.

As is well known, originalism was epitomized by the late Justice Scalia, and it is reflected in the recent Dobbs decision, overruling Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey’s protection of the right of pregnant persons to decide whether to terminate their pregnancies. According to these folks, the foregoing list of rights is made-up, subjective, and boundless; it’s the product of lawless liberals reading their own visions of moral and political utopia into the Constitution under the guise of interpreting it.

But according to the competing view, this list represents what Casey called a “rational continuum” of ordered liberty stemming from “reasoned judgment” concerning rights to make certain basic decisions fundamentally affecting their identity, destiny, or way of life.

In fact, I argue, the list is actually pretty conservative. It consists of many of the most important decisions people make in their lifetimes. And those are the kinds of decisions that hardly anyone, conservative or liberal, wants the government to tell them how to make.

In this new book, I analyze these opposing theories about how courts have developed the list of basic liberties. According to originalists like Justice Scalia, this practice of substantive due process is nothing more than elitist judges imposing their “moral predilections” upon the rest of us in defiance of the Constitution.

By contrast, moral readers argue that this line of cases has been built out over time through ordinary common law constitutional interpretation: reasoning by analogy from one case to the next on the basis of experience, new insights, and moral learning, and deciding whether to extend rights previously recognized based on the basic reasons we protected those rights in the first place.

The Record: The Record: What makes substantive due process so controversial? Is it the rights themselves?

The conservative originalists say their objections are primarily methodological—to the approach to interpretation reflected in substantive due process. They say that originalism is an objective method of constitutional interpretation that is faithful to the original meaning of the Constitution when the provision was ratified, either in 1791 with the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause or in 1868 with the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause. They say that substantive due process rejects any aspiration to fidelity to the Constitution.

I defend a moral reading of the Constitution and substantive due process—over and against that originalist approach—as more faithful to the Constitution. My approach, and the leading substantive due process decisions, conceive of the Constitution as a basic charter of abstract aspirational principles promising liberty and equality to all. It’s not, as originalists assume, a code of specific, enumerated rights or a deposit of concrete historical practices concerning liberty and equality as of 1791 or 1868.

I argue that if originalism were consistently applied, it would reduce our Constitution from a basic charter that is to be built out over time on the basis of experience, new insights, and moral progress into a stagnant, hidebound document and deposit of historical practices as of 1791 or 1868.

… liberals and progressives must learn to appreciate the virtues of federalism in our circumstances of disagreement and polarization. I encourage them to turn to state courts interpreting state constitutions instead of federal courts interpreting the US Constitution.

The Record: How does the Supreme Court, in its current makeup, view substantive due process? And what does that mean for those in favor of the doctrine?

The current Supreme Court made its extremely critical view of substantive due process devastatingly clear in Dobbs. Justice Alito’s majority opinion asserted that the decision did not “cast doubt” upon precedents not involving abortion, but if the Court were to apply Dobbs’s approach to substantive due process—limiting our basic liberties to those specifically protected in the concrete historical practices of 1868—it would not protect rights such as contraception or the right of same-sex couples to intimate association or to marry.

You also asked what that means for those who support protecting such basic liberties, which is the subject of the final chapter of the book, called “The Future of Substantive Due Process.”

There, I argue that liberals and progressives must open their eyes and stop harboring any hopes that federal courts will protect their rights or pursue (or even enable) liberal or progressive change. I exhort them to turn more to legislatures and executives than to courts. Here I include not only the national legislature and executive but also state and local governments.

Furthermore, liberals and progressives must learn to appreciate the virtues of federalism in our circumstances of disagreement and polarization. I encourage them to turn to state courts interpreting state constitutions instead of federal courts interpreting the US Constitution.

From the movement to secure queer rights between the infamous originalist Bowers decision (rejecting a right to same-sex intimacy) in 1986 to Obergefell (protecting the right of same-sex couples to marry), you see litigators’ strategies emphasized winning in state courts and avoiding federal courts until they had already secured the right to marry in most states. I argue in the book that federalism is the structure of resistance to national power.

The Record: Did anything surprise you while you were researching or thinking about your book?

Yes, a couple of things surprised me. The first is the conservatism of our actual practice of substantive due process (when you get beyond the cacophony of other conservatives’ objections to it).

Let me explain. The biggest defenders of substantive due process are liberals and, for the most part, its biggest critics are conservatives. But, through writing this book, I came to see many ways in which its development has actually been conservative in two respects: one, every substantive due process decision protecting basic liberties from Roe through Obergefell was written by a Republican justice, and most of them had Republican majorities.

For example, Justice Kennedy’s decisions in Lawrence and Obergefell, had a conservative cast to them. His opinions emphasize not just individual choice or autonomy (the ground for justifying these rights associated mostly with liberals) but also the moral goods promoted by protecting those rights: commitment, intimacy, loyalty, mutuality, stability, and the like. Also, when you look at that list of basic liberties, you’ll see that it has protected rights to make certain significant decisions which most conservatives want to make free of state compulsion, just as liberals do. It has not protected any rights that anyone could fairly call frivolous or idiosyncratic.

The second thing that surprised me is how weak some of the conservative arguments against substantive due process are. For example, Justice Scalia argued that substantive due process—Lawrence in particular—put us on a slippery slope to “the end of all morals legislation.” His list of traditional morals laws that were imperiled by protecting queer rights includes laws forbidding bigamy, adult incest, prostitution, adultery, and bestiality. This argument is not only deeply offensive but also specious.

His slippery slope argument asserts that once we recognize same-sex marriage, we won’t be able to draw a line short of extending the right to marry two or more unions, whether polygamy or polyamory. Maybe so, if constitutional change is a matter of making arguments in a seminar room for extending abstract principles like freedom to choose. But when you ponder the processes of constitutional change that got us to Lawrence and Obergefell to begin with, you’ll see that it’s highly unlikely that the Court is about to recognize many of the rights on Scalia’s list.