BU Humanists at Work: Meet Micah Goodrich

Micah Goodrich’s scholarship knits together his two specialties in seemingly disjunct areas: medieval studies and trans studies. His recent and current work considers what he’s coined as “trans natures,” or “ways of inhabiting a body and inhabiting an environment that are in dialogue with medieval natural philosophy.”

Micah Goodrich’s scholarship knits together his two specialties in seemingly disjunct areas: medieval studies and trans studies. His recent and current work considers what he’s coined as “trans natures,” or “ways of inhabiting a body and inhabiting an environment that are in dialogue with medieval natural philosophy.”

In his publications and in the classroom, he encourages readers and students to consider nature as a “template” against which the human body has been and still is measured. When applying this lens to the medieval period, readers and students encounter bodies that challenge the socially-constructed ideas about bodily “norms” that we live with today. “Compared to our modern medical ideas about a hermetically sealed body, the medieval body was very porous and open to transformation. There are so many spectacular ways that the body is understood in the past. It can help us to change our sometimes rigid ideas about our bodies now,” Goodrich notes.

Goodrich points to the example of the rebis, which he describes as a figure in European medieval alchemy that dually represents alchemical processes and Christ as the perfection of the human form. As a representation of Christ, the rebis also represents the alchemist’s desire to find the most divine, perfect aspect of nature. The rebis is usually described or depicted as a human body with two heads, one male and one female. “The fact that this apex of nature is understood in this kind of trans figure is really powerful to me. Representations of non-normative bodies as the perfection of nature drive a lot of my work,” says Goodrich.

Goodrich takes an expansive view of the word “nature” in his work, considering its semantics as “a disposition or way of being as well as something that is of the environment.” He finds that thinking about the natural inclinations of the human body in a time that predates modern sexology illuminates “other kinds of natures and other ways that we can be.”

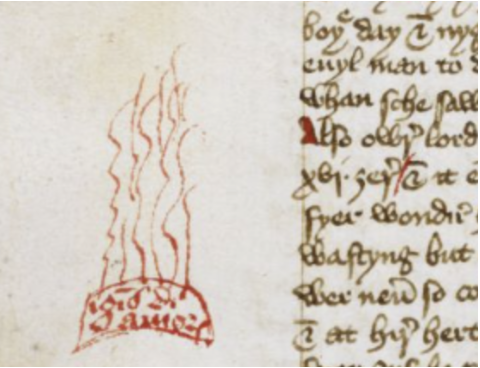

In a current short piece that he is working on, Goodrich takes up the example of Margery Kempe and “tries to understand her trans natures” as her body shifts between the elemental states of water and fire (two of the states of matter in medieval science and philosophy). Kempe was a fourteenth-century Christian mystic known for her extreme piety, which she expressed so excessively through constant tears that she became a social outcast. The piece interrogates how Margery Kempe “embodies a trans state where her nature and temperature is drastically changing” To probe this question, Goodrich considers scientific and philosophical medieval texts and Kempe’s autobiographical writings in conjunction with contemporary trans memoirs that describe experiences like having your body temperature rise by several degrees as a result of taking testosterone.

This kind of scholarship speaks to Goodrich’s life-long interest in the intersections between “the strange and the familiar” that he has found to engage students as well. In the classroom, he loves exploring the tensions between the strangeness and familiarity of the medieval world and our modern world with students, noting that leaning into the unfamiliar creates “spaces where we can be self-reflective about our own world.”

Goodrich acknowledges that the strangeness of the medieval world and of early English can feel “daunting.” However, he views engagement with the pre-modern as a valuable exercise with practical applications for today’s undergraduate. “I think that reading pre-modern texts asks students to face the temporal disjunctions that we must attend to right now when we’re thinking about the long spectrum of something like climate change, for example. That temporal stretching of the mind asks you to dislocate from your own time and inhabit a different world where you are not. We have to do that in the other direction, thinking about what a future holds well beyond when we are here for it. That similar kind of logic extends to pre-modern texts, and that kind of thinking is important work that takes time to learn how to do.”

The other reason students might give medieval literature a try? “It’s also just fun. Medieval texts are wild!” Goodrich says and laughs. Next semester, Goodrich will be teaching Medieval Worlds through the Body and a literature course in disability studies that spans several centuries. As a first generation student, he strives to “make the classroom a space where students can rely on different kinds of resources than the ones that are [typically] expected of them,” namely on themselves and on each other. He designs his syllabus to be as flexible as possible, so students from all disciplines and backgrounds can “bring their own expertise to the table in ways that [he] might not have imagined.”

Beyond the classroom, Goodrich encourages students who are interested in trans studies or in the medieval period to “come find me,” adding “I’m always up for chatting.” Despite his passion for the distant past, Goodrich embraces his present at BU as a visiting faculty member “The students are really incredible, and it’s only week five. I feel very fortunate,” he says with a smile.