How has China helped the green transformation along the Belt and Road: Four Channels

By Yan Wang

As the deadline for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) draws near, the world economy faces headwinds from trade protections, supply-chain disruptions and shrinking development assistance. According to the OECD, official development assistance (ODA) from member countries declined by 7.1% in 2024. Against this backdrop, finding workable solutions to a polycrisis in climate and environment, as well as poverty reduction has never been more urgent.

Since its launch, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has fueled economic and social development across participating economies. Yet its early emphasis on infrastructure connectivity also came with a price––higher carbon emissions and local environmental stress. The Chinese government responded in 2017 by introducing the Green Belt and Road Initiative (GBRI), a set of policies prioritizing low-carbon development and climate mitigation.

In 2017, four ministries jointly issued two key policies aimed at “greening the BRI,” which advanced stronger environmental protection principles for the BRI, emphasizing support for low-carbon development, biodiversity conservation, and climate change mitigation. But how effective have these 2017 green policy shifts really been? Have they actually helped participating economies move toward cleaner, low-carbon growth?

A new working paper by Xiaolin Wang, Ran Jin and Yan Wang offers an empirical answer. The authors analyzed 139 countries (including 52 countries along the Belt and Road) from 2013 to 2022, estimating a difference-in-differences (DiD) model that treats the 2017 GBRI policies as a quasi-natural experiment to evaluate their impact on carbon intensity (CO₂/GDP) in BRI economies.

The results indicate that the GBRI has made a real difference in cutting carbon intensity. Thanks to the policy coordination across partner countries, BRI countries saw a significantly larger decline in carbon intensity than similar non-BRI countries, with a relative reduction of 5.9 percent. However, the progress weakens when China’s outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) expands in more carbon-heavy sectors.

The study also finds that the green impact of the GBRI isn’t same everywhere. It is pronounced among low-income and high-income groups but not statistically strong for lower-middle- and upper-middle-income groups. This observation is consistent with the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) where growth priorities may dominate mitigation in the middle of the income distribution. Moreover, government effectiveness and the rule of law see a much bigger payoff from the GBRI, underscoring that the role of governance matter just as much as investment.

How does the GBRI promote the green transition? The paper highlights four underlying mechanisms that operate as a self-reinforcing loop.

- Low-carbon technology trade accelerates the adoption of renewables and energy-efficiency solutions in host economies, improving the power mix and lowering emissions per unit of output.

- The expansion of digital infrastructure and Information and Communication Technology (ICT) services (including FinTech) makes it easier to monitor, manage and reduce carbon intensity.

- Industrial upgrading shifts economic activities toward cleaner, higher value-added segments, while green standards become embedded in investment, trade and supply-chain practices.

- Policy and institutional coordination enhance host country regulation, green finance guidelines, disclosure and accountability. This raises implementation capacity and predictability, magnifying the long-run effects of the other channels and closing the “technology trade–digital–industry–institution” loop.

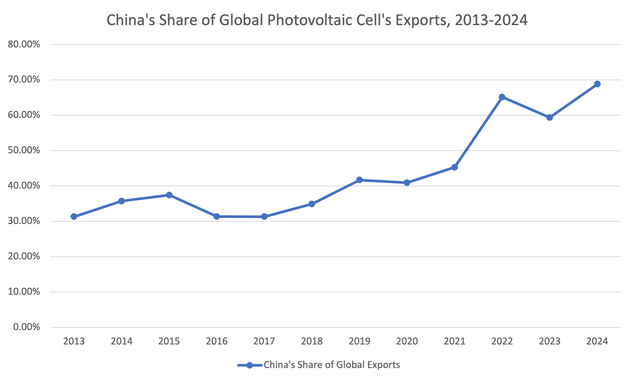

Overall, China’s GBRI is a multi-faceted package spanning trade, investment, technological transfer, digital connectivity and industrial upgrading. China is in a unique position to offer such packages to GBRI countries. As the largest trading partner for more than 120 countries, the largest manufacturer and exporter of photovoltaic cells and a nation that has opened its huge market to many low-income economies, China has the reach, the resources and technological know-how to promote greener growth across the Belt and Road network. As illustrated in Figure 1, China’s share of global photovoltaic cells export reached 70 percent in 2024.

Figure 1: China’s export of Photovoltaic Cell’s in global export, 2013-2024

Looking ahead, three implications stand out for making the Belt and Road greener. First, scale up trade in low-carbon technologies so that clean solutions become cheaper and more accessible. Second, make OFDI truly green by setting clear environmental criteria at project screening stage, and by enabling refinancing and retrofitting existing high-carbon assets to lower their emissions. Third, enhance governance and the rule of law in partner countries so that green commitments can translate into enforceable, measurable and accountable outcomes. Collectively, these steps can help turn the GBRI from an ambitious vision into a living example of sustainable global cooperation.

*

Read the Working Paper