Chart of the Week: Debt Distress: The Hidden Barrier to Scaling Up Adaptation Finance

By Rishikesh Ram Bhandary and Tim Hirschel-Burns

As negotiations at the 30th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30) in Belém, Brazil go down to the wire, one of the key topics awaiting resolution is adaptation finance. Adaptation finance is geared towards helping countries address the impacts of climate change. It can include measures ranging from introducing drought-resistant crops to building sea walls to protect against rising sea levels.

Adaptation finance is only a small fraction of climate finance. According to the Climate Policy Initiative, adaptation finance stood at only $65 billion in 2025, in contrast to mitigation finance (which aims to reduce or prevent greenhouse gas emissions) at $1.7 trillion. What is more, with climate change only intensifying, the estimates for adaptation finance needs have gone up. To address this major funding shortfall, at COP26 in Glasgow in 2021 governments agreed to double adaptation finance (against 2019 levels) to $38 billion by 2025. Countries are for a tripling of adaptation finance to reach $120 billion by 2035.

Scaling up adaptation finance is crucial. Underinvestment in adaptation will simply intensify the vicious cycle between climate impacts and debt: high debt costs prevent countries from making climate investments, leaving them exposed to intensifying climate impacts that cause damage that in turn exacerbates their debt. Helping fuel this cycle is the fact that climate-vulnerable countries face a high risk premium that increases the interest rates at which they can borrow.

However, an exclusive focus on how much adaptation finance is needed can overlook the vital question of how that finance is delivered. Put simply, many of the countries most in need of adaptation finance would struggle to take on anything but highly concessional loans or grants.

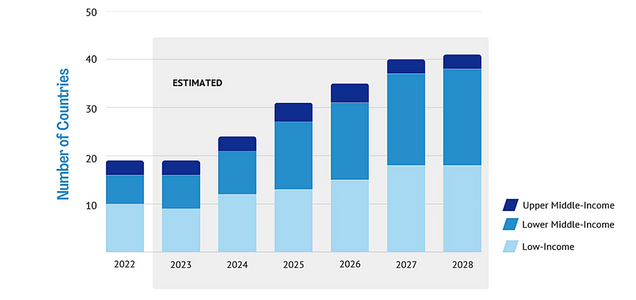

In a study published this year in Development, Marina Zucker-Marques, Kevin P. Gallagher and Ulrich Volz analyzed what would happen if countries were to borrow the sums needed to meet climate and development goals. The result is shown in Figure 1 below: by 2028, 42 out of 62 countries using the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Debt Sustainability Framework for Low-Income Countries (LIC DSF) are expected to breach solvency thresholds. Solvency thresholds are determined using a range of metrics including the value of external debt as a fraction of gross domestic product (GDP) and exports, debt servicing costs as a fraction of exports and revenue and total debt as a fraction of GDP. In other words, there is virtually no fiscal space in those countries to increase borrowing.

Figure 1: Number of Countries Breaching Solvency Indicators of External Debt Sustainability, 2022–2028, by Income Group

This finding echoes an earlier study by IMF officials. The paper found that out of the 29 countries that have submitted National Adaptation Plans with financing needs, only seven actually have the fiscal space to make those investments.

What is clear is that while increasing the scale of adaptation finance is absolutely necessary, this needs to be in the form of concessional finance. If not, countries in debt distress or with elevated debt levels may be locked out from actually using that finance. Therefore, governments must also move to urgently fix the sovereign debt architecture and converge around a debt relief initiative to give countries a clean slate to invest where needed. COP30 cannot solve these problems on its own, but it can catalyze momentum for action on debt and ensuring the concessionality of adaptation finance.