IMF Lending Returns to Low Levels While the PBOC Continues as the Largest Provider of Currency Swaps: Insights from the Updated Global Financial Safety Net Tracker

By Marina Zucker-Marques, Laurissa Mühlich, and Barbara Fritz

In a world beset by lower growth prospects, unprecedented uncertainty in international trade and high debt service pressures, access to timely financial resources is essential for central banks and governments in order to stabilize their economies without compromising spending on domestic priorities. This crisis financing comes from the so-called Global Financial Safety Net (GFSN)—a network of institutions and arrangements that includes the International Monetary Fund (IMF), regional financial arrangements (RFAs) and central bank currency swaps. Although the GFSN is the cornerstone of the global financial architecture, comprehensive and up-to-date systematic analyses that encompass all elements of the GFSN have dwindled in recent years since the COVID-19 pandemic.

The GFSN has increased its firepower since 2020, yet the newest release of the GFSN Tracker—a first-of-its kind data interactive co-produced by the Boston University Global Development Policy Center (GDP Center), Freie Universität Berlin and United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)—reveals that the distribution of GFSN financing is highly asymmetric, with developing countries in general and Africa in particular eligible for the least level of financing and subject to the most onerous conditions. The GFSN Tracker maps actual and historical emergency finance arrangements as well as lending capacity available to countries through the GFSN.

The newly updated interactive tracker now exhibits the lending capacity of the GFSN through December 2024. Moreover, it highlights new arrangements signed and utilized between May 2024 (previous update) and March 2025.

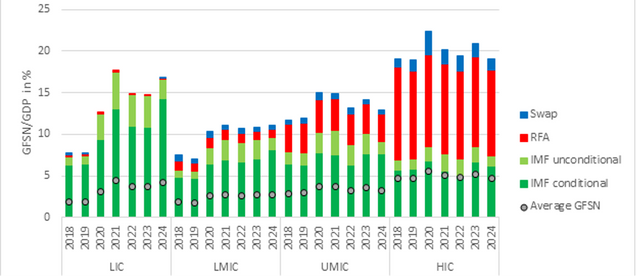

The overall lending capacity of the GFSN has increased considerably since 2020, in particular during the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet that expansion has occurred with unequal results: the lowest level of emergency finance is available for middle-income countries. For low-income countries, the quantity of emergency finance is relatively high, which was particularly evident in 2021 when the IMF increased the access limit for these countries to up to 150 percent of quota in the non-conditional lines. However, the bulk of accessible crisis finance for low-income countries is tied to policy reform requirements in standard conditional IMF programs. To the contrary, for high-income countries, the major source of emergency liquidity has become central bank currency swaps that are voluminous, unconditional and immediately accessible during crises.

Figure 1: Access to the GFSN by Income Group, As Share of GDP (%)

Updates from the IMF: Widespread Reluctance to Apply for Programs

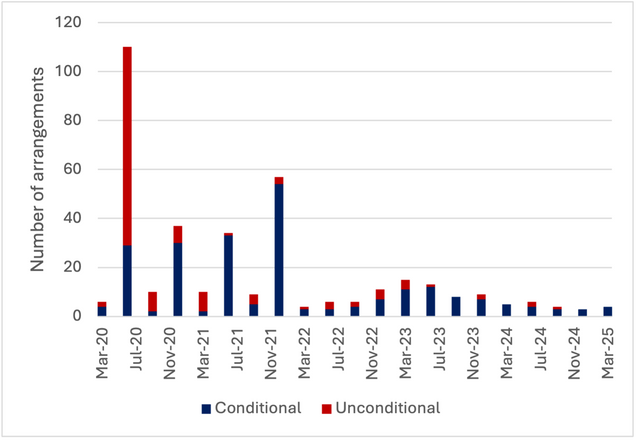

Compared to the surge in IMF loan activity during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, recent engagement of the Fund has been markedly lower. In 2020, the IMF approved 163 loan arrangements, with activity peaking at 110 new agreements in the second quarter, as illustrated in Figure 2. The sharp spike reflected the global effort to respond to an unprecedented external shock, and most of the arrangements during that period were from the Fund’s unconditional lending windows, such as the Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI) and Rapid Credit Facility (RCF). In contrast, between 2024 and March 2025, only 13 new IMF loan agreements were identified: nine were in Africa, three in Latin America and the Caribbean and one in Asia. Only one out of these 13 arrangements was made under the unconditional RCF window (see below). Despite the fact that public debt in developing countries is reaching record heights and external debt service is rising, especially in lower-income countries in Africa, these numbers reflect that the demand for new IMF funds is not increasing. This reluctance by countries to apply to IMF programs could be driven by the IMF’s fiscal adjustment requirements that negatively impact growth, poverty and inequality.

Figure 2: Number of IMF Commitments by Loan Type, January 2020–March 2025 (By Quarter)

During the tracked period between May 2024 and March 2025, the IMF approved over $36 billion in new lending, as detailed in Table 1. The majority of this funding—more than $22 billion—was allocated through conditional lending arrangements that require recipient countries to implement agreed-upon policy reforms. In addition, two countries accessed the IMF’s unconditional financing windows: Chile renewed its precautionary Flexible Credit Line (FCL) at the amount of $13.9 billion, while Guinea received $71 million through the Rapid Credit Facility (RCF) due to a fuel depot explosion that generated balance of payment needs.

Table 1: Approved IMF Arrangements

Updates from Regional Financial Arrangements: The EU Macro-Financial Assistance (MFA) as Key Liquidity Provider

Since the last GFSN Tracker update, there have been seven new lending commitments from RFAs to five different countries, totaling $7.1 billion. Egypt was the largest borrower, receiving over $5 billion through the European Union’s Macro-Financial Assistance (MFA) program—one disbursement in December 2024 and another in March 2025.

Jordan also secured MFA support, with cumulative commitments exceeding $1 billion. Additionally, the Maldives accessed $400 million from the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), Ecuador borrowed $300 million from the Latin American Reserve Fund (FLAR) and Armenia received $100 million from the Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development (EFSD).

All five countries are accessing RFA financing in conjunction with other liquidity sources in the GFSN, such as several RFAs or the IMF. For instance, the MFA loans to Egypt and Jordan are in addition to their earlier borrowing from the Arab Monetary Fund and primarily in connection with repayment obligations with ongoing IMF agreements.

Table 2: Approved RFA Arrangements

Updates from Central Bank Currency Swaps: the PBOC Continues as the Largest Provider of Currency Swaps

As of March 31, 2025, there were 84 active central bank currency swap agreements worldwide. Among them, 30 are infinite and unlimited arrangements—meaning they have no nominal limits—exclusively between the US Federal Reserve and so-called “Gang of Five” advanced economy central banks: the European Central Bank, Bank of England, Bank of Japan, Bank of Canada and Swiss National Bank. These agreements are primarily designed to provide liquidity in moments of market stress and are a critical part of the GFSN.

Outside of these unlimited arrangements, China currently stands out as the largest provider of swap lines. As Table 3 shows, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) maintains 21 active agreements, ten of which are with high-income countries. These high-income swaps often serve as a mechanism to enhance offshore renminbi (RMB) liquidity. The remaining agreements include six with upper-middle-income countries and five with lower-middle-income countries. China’s growing role in the international monetary system is increasingly reflected through these swap lines, which form a key component of its broader financial diplomacy toolkit. However, compared to the last update in May 2024, we observed a slight decline in the number of active Chinese swaps. This decrease is due to the expiration of swaps with Albania, the UK and South Africa, which were not renewed by the cut-off date of this research. There were also other cases of swap expirations that, as of March 2025, had not been renewed. Examples include Turkey’s bilateral swaps with the United Arab Emirates and Qatar, as well as the swap from Australia to Indonesia.

Japan and South Korea also remain significant providers of central bank swap lines. The Bank of Japan currently has 12 valid arrangements: seven with high-income countries, three with upper-middle-income economies and two with lower-middle-income partners. South Korea maintains eight active agreements, evenly split between high-income and upper-middle-income countries.

However, access to central bank swap lines remains heavily concentrated among higher-income countries. At present, only one low-income country—Ethiopia—has a known active swap line. This agreement, extended by the United Arab Emirates, highlights the broader challenge of inclusion within the global liquidity safety net.

Table 3: Number and Distribution (By Income Group) of Valid Central Bank Currency Swaps as of March 31, 2025 and Comparison to May 2024

In terms of volume, the 54 central bank currency swap lines that are not infinite and unlimited amount to nearly $1.1 trillion in total available liquidity, of which $521 billion is offered to high-income countries and $480 billion to upper-middle-income countries, with just $98 billion to lower-middle-income countries and less than $1 billion to low-income countries.

Between May 2024 and March 2025, the GFSN Tracker identified 19 swaps that were either renewed, extended or newly established, with a combined notional value of $269 billion. Eighteen of these were renewals or extensions, including five led by China and five by Japan. Additional activity came from Australia, South Korea, Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore. Only one agreement was newly established during this period: the above-mentioned swap line from the UAE to Ethiopia. While renewal activity underscores the continued importance of these arrangements, the limited number of new agreements suggests a relatively cautious expansion of the network over the past year.

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

With an uncertain global economic outlook, deteriorating trade relationships and high public debt burdens in developing countries, the need for an adequate GFSN is clear. This includes increasing IMF quotas—according to our estimations, by at least 127 percent if lower-income countries are to have access to levels of financing similar to high-income countries. Moreover, this also requires emergency finance that provides for similarly timely, flexible and unconditional access to make sure that developing countries do not have to compromise on domestic development priorities due to crisis events. The actual crisis finance activities in the GFSN show a continued dominance of central bank currency swaps: while the GFSN Tracker identified $269 billion in new, renewed and extended swaps between May 2024 and March 2025, RFAs committed just slightly over $7 billion and the IMF saw $36 billion in new lending agreements in the same period.

Although the IMF provides extensive emergency finance for low-income countries, the predominant source of its funding is standard conditional lending facilities that require more time to be disbursed and have higher obligations in terms of policy reform. If the IMF aims to remain the center of the GFSN, as the signatories of the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FFD4) outcome document committed to in Seville, it is fundamental for the IMF to strengthen unconditional and quickly accessible lending facilities for low- and middle-income countries by maintaining their access limits at the same high-level as during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Further, central bank currency swaps and RFAs remain an important element of the GFSN that require strengthening, particularly for developing countries and emerging markets. Due to their limited lending capacity, many member countries utilize their RFAs in combination with other GFSN elements. To design an effective GFSN for crises, RFAs should be strengthened as easily accessible emergency finance in coordination with other GFSN elements.

Designing a more resilient and equitable Global Financial Safety Net demands coordinated reforms across all its pillars—IMF financing, central bank currency swaps and Regional Financial Arrangements. Only through such a comprehensive, inclusive approach can the GFSN truly fulfill its promise as a global crisis response architecture that sustains growth and stability for all countries, regardless of income level.

Barbara Fritz is a professor at the Freie Universität Berlin, with a joint appointment at the Department of Economics and the Institute for Latin American Studies.

*

阅读博客文章