Still Constraining Climate Policy: Assessing the Climate-Related Industrial Policy Landscape in Five Figures

By Rachel Thrasher and Praveena Bandara

The consensus around the urgent need for climate policy continues to grow. In a July 2025 address, UN Secretary-General António Guterres lauded this new “moment of opportunity” by launching a technical report that highlights the benefits and inevitability of a global energy transition. The report highlights the rapid progress that has been made in the past 10 years, and reminds the world that there is still have a long way to go. The report identifies a few obstacles to this progress and urges governments to take more ambitious domestic policy action, and to “align [trade policies and investment agreements] … with, and actively support, the transition to sustainable and inclusive development.”

Meanwhile, countries continue to face rapidly changing climate realities and skyrocketing demand for transition minerals, both of which necessitate immediate action. In a new working paper, we seek to understand the extent to which these trade and investment agreements may be posing an obstacle to country climate policy action. First, we seek to describe the landscape of climate-related industrial policies currently pursued by countries. Second, we ask to what extent might countries face legal constraints in their pursuit of such policies under the current international trade and investment regime.

Our research draws from various conceptual definitions of industrial policies found in the literature, which include those interventions that aim to modify prices across sectors or direct resources toward targeted activities, thus deliberately shaping or transforming the structure or composition of economic activity. To get at that concept, we drew from Global Trade Alert (GTA) policy data, omitting policies with economy-wide impacts and those that impact a very high number (>200) of products. To identify only those interventions that are “climate-related,” we included only those interventions that are predicted to impact low-carbon technology (LCT) products and critical minerals.

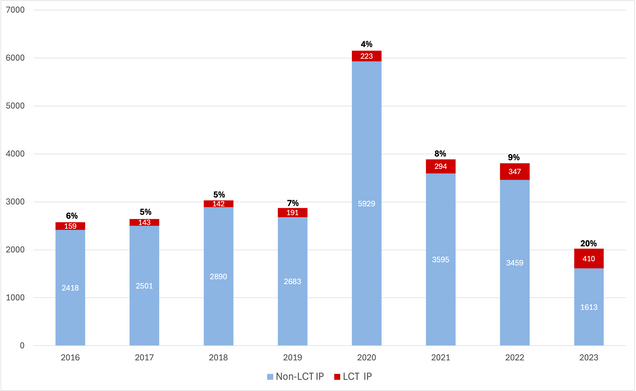

The research shows that countries have been introducing an increasing number of climate-related industrial policies over the past five years. According to our research, the proportion of industrial policies aimed at climate-related sectors has gone from five percent to 20 percent (as a share of total industrial policies) in the five years from 2018-2023 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Evolution of Low-Carbon Technology Policies

Our research breaks down policy interventions by the types of policy categories provided by the GTA data team, including subsidies and state aid, export and import policies, localization policies, foreign investment policies, public procurement policies and trade defense instruments. What is clear is that subsidies and state aid make up the bulk of most of the world’s climate-related industrial policies, with export and import policies taking a distant second place (Figure 2). Together the two categories amount to 92.5 percent of all climate-related industrial policies in our dataset.

Figure 2: Types of Industrial Policies Used

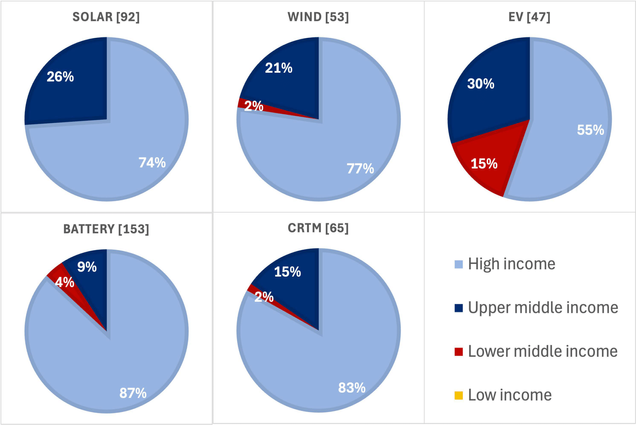

We also broke down the policies according to the sector of primary predicted impact, highlighting that the majority of the policy impact takes place in the battery sector and most of those policies are implemented by high-income and upper-middle income countries (Figure 3). Notably, it was the electric vehicle (EV) industry that saw the greatest number of policy interventions by lower-middle-income countries; however, the red slice of the EV pie chart represents almost only the work of India, and the dark blue is largely policy engagement by China alone. Indeed, besides one policy intervention each by Namibia, Zimbabwe and Nepal, all policies represented in the red slices below are a result of India’s actions.

Figure 3: Industrial Policies by Income Group and Industry, 2023

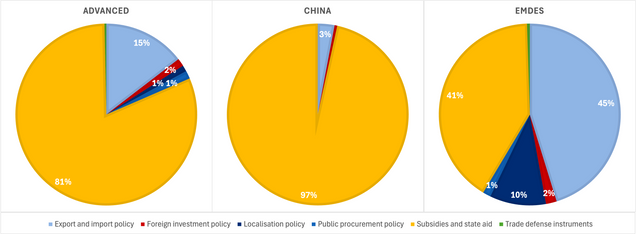

One of our most significant findings is that countries in different income groups tend to rely on a different mix of policy instruments. As Figure 4 demonstrates, advanced economies (AEs) relied almost entirely on subsidies from 2021-2023, while emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) (excluding China) relied much more heavily on export and import policy instruments. Even more crucially, 10 percent of the policies in EMDEs fall into the localization category. This is unsurprising given that a robust subsidies program often requires fiscal resources not readily available to EMDEs.

Figure 4: Industrial Policy by Country Group, 2021-2023

This is particularly significant given the status of certain policies under global trade and investment rules. While global trade rules found in the agreements of the World Trade Organization (WTO), bilateral and regional free trade agreements (FTAs), and international investment agreements (IIAs) have set general standards of non-discrimination and non-arbitrariness for all policy measures by members, particular policies are treated with more suspicion. Tariffs and tariff quotas must be negotiated, scheduled and maintained below a particular ceiling over time. Subsidies, while permitted, can be challenged by other member states for their cross-border economic impacts. Other policies like export and import quantitative restrictions and local content requirements are outright prohibited in the vast majority of these agreements.

To assess the constraints that trade and investment rules might place on the policy toolkits of our country groups, we assigned a 0 for all policies that are only constrained by the most basic non-discrimination and non-arbitrariness standards, a 1 for all policies that are allowed but regulated in specific ways (e.g., tariffs and subsidies) and a 2 for all policies that are specifically prohibited (e.g., local content requirements). Figure 5 demonstrates that the policy toolkit for EMDEs is consistently more constrained by the rules than the policy toolkit for AEs.

Figure 5: Average Policy Scores by Country Group

These findings may not tell the whole story. Since all policies are held up to the non-discrimination and non-arbitrariness standards, those standards are the ones most frequently invoked in both WTO and investment jurisprudence. Additionally, in investor-state disputes, it is EMDE host states that are more frequently on the receiving end of challenges to their domestic policies. What this means is that while many countries are actively engaged in climate-related industrial policymaking, EMDEs face a higher risk of international dispute or challenge.

The business of climate-related industrial policy is booming. AEs tend to draw from a different set of tools than their EMDE counterparts, however, in such a way that EMDEs are more likely to be constrained by the global trade and investment rules. To address this inequality, the WTO, FTAs and IIAs will need to be renegotiated and reformed with the goal of removing obstacles to countries striving simultaneously for climate and development goals. Trade and investment rules need not shift with every political wind, but those that create policy space for a just transition can become pillars of a more sustainable global economy.

Praveena Bandara is a Senior Research Associate at the Net Zero Industrial Policy Lab at John’s Hopkins University. She was previously a Global Economic Governance Post-doctoral Research Fellow at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center.

Read the Working Paper