FAQs: Data Analysis on Chinese Overseas Lending and Development Finance

By Oyintarelado Moses, Ishana Ratan and Lucas Engel

From 2008-2021, China’s development finance institutions (DFIs), China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM), provided approximately $500 billion in overseas development finance (ODF), an amount nearly on the scale of World Bank lending during the same time period.

The Boston University Global Development Policy Center (GDP Center) is dedicated to providing open-sourced data products for researchers, policymakers, journalists and the general public. Through its Data Analysis for Transparency and Accountability (D.A.T.A.) research group, the Global China Initiative (GCI) maintains and hosts a series of five databases tracking Chinese overseas lending and development finance (OLDF) and projects for the purpose of transparency and evaluation. GCI classifies Chinese ODF as loans from China’s two main DFIs, while OLDF includes any lending from other Chinese financiers such as commercial banks or companies. The GDP Center views GCI database products as public goods and makes them accessible to those seeking insights into the trends and impacts of Chinese OLDF.

GCI databases are global, regional and sectoral in scope. They include the China’s Overseas Development Finance (CODF) Database, the Chinese Loans to Africa (CLA) Database, the Chinese Loans to Latin America and the Caribbean (CLLAC) Database, the China’s Global Energy Finance (CGEF) Database and the China’s Global Power (CGP) Database. Each database’s methodology is explained in detail in the Database Methodology Guidebook, 2023.

This blog provides answers to frequently asked questions regarding the scope, methodology and distinguishing features of GCI databases.

What do GCI databases on Chinese overseas lending and development finance track?

Of the five databases GCI manages and maintains, four databases (CODF Database, CLA Database, CGEF Database, CLLAC Database) exclusively track international sovereign loans, also known as public and publicly guaranteed (PPG) loans, issued by Chinese financial institutions. These databases track several loan attributes, including the lender, the recipient, the sector and the loan amount. Whether a particular financial transaction is tracked by one or more of the GCI databases depends primarily on the financing entity, recipient characteristics and whether the loan has been signed.

The CGP Database tracks Chinese-financed power plants, their gigawatt capacity and their carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions.

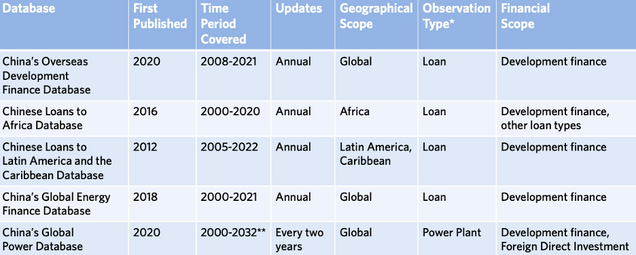

The basic information and scope of GCI databases is presented in Table 1.

Table 1: GCI Database Basic Information and Scope

Note: * “Loan” refers to loan commitments, not debt or disbursement amounts. ** CGP tracks the year or projected year of commission for electric power generating units.

GCI databases can be distinguished according to lending institutions. Three GDP Center databases assess lending from China’s two main DFIs: CDB and CHEXIM. These include the CODF Database, CGEF Database and the CLLAC Database. DFIs are independent public institutions with policy mandates for supporting development, which deploy project-specific loans and other financial instruments under a government-led strategy. The CLA Database also tracks loans from Chinese commercial banks, government entities, companies and other financiers in addition to development finance provided by CDB and CHEXIM. Projects in the CGP Database are financed by development finance and foreign direct investment from Chinese companies.

The four GCI databases (CODF Database, CLA Database, CGEF Database, CLLAC Database) that exclusively track ppg loans all focus on sovereign borrowers, inter-governmental bodies, majority state-owned entities and minority state-owned entities with sovereign guarantees. In determining what characteristics a loan recipient must possess for a loan to qualify as an ppg loan, GCI databases rely heavily on guidance issued by the World Bank, which considers an entity with more than 50 percent government ownership, including state-owned enterprises, a sovereign borrower. In cases where there is 50 percent or less government ownership, the entity must have a sovereign (government) guarantee for the loan to qualify. For loan-financed projects in the CGP Database, these parameters still apply, while FDI-financed projects are included where the overall share of investment provided by the Chinese investor is more than 10 percent.

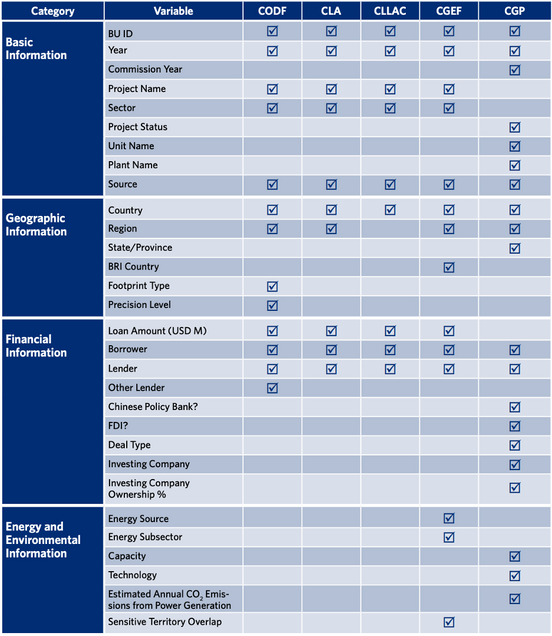

The variables included in each database are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Variables Included in Each GCI Database

The CODF Database provides precise geolocated information for projects receiving Chinese ODF and maps their proximity to three types of sensitive territories: potential critical habitats, Indigenous peoples’ land and national protected areas. Of 1,099 loans tracked in the CODF Database, 736 have precise geographic footprints, and are shown in the visual map on the interactive website, while the remaining 363 projects without precise footprints are included in the full table of projects below the map. Projects are evaluated for geolocation using a high level of verification.

Why do most GCI databases only track public and publicly guaranteed loans?

GCI databases only track PPG loans (international sovereign loans) for the purpose of being able to compare the data with sovereign loan data from the World Bank International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and International Development Association. The purpose of analyzing Chinese OLDF is primarily to understand the trends and development impacts of this financing. Since World Bank loan financing has development goals tied to each transaction, this standard of comparison is most suitable to evaluate to what extent the development impacts of China’s overseas financing compare to other DFI finance.

What time periods do GCI databases track and why?

All databases track financing commitments during time periods before and after the announcement of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013. However, due to the scopes of each database, overall timeframes differ slightly. The CODF Database currently tracks loans from 2008-2021, to enable analysis of financing trends during and after the global financial crisis. The CLA Database tracks loans from 2000-2022 to identify Chinese OLDF trends following global debt write-off initiatives that many African countries were involved in, including the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative. The CLLAC Database loan data is from 2005-2022, to cover Chinese ODF lending to LAC following the start of LAC’s commodity boom. The CGEF Database covers financing from 2000-2022 to capture all energy finance trends globally over an expansive number of years. The CGP Database covers the year of commission or projected year of commission of power plants from 2000-2032.

Despite the different time ranges for each database, users can review relevant data for the BRI period by extracting data from 2013-2022.

What methodologies do GCI researchers use to track this data?

GCI researchers use a systematic replicable process to identify and collect detailed data on each loan. Loans are first identified through an algorithmic and manual search. Two main tools, Microsoft Azure and GDELT, are used to web scrape news articles with information about Chinese projects. Azure has broad coverage and very precise search results, but predominantly includes English language sources, so GDELT is used to supplement local language sources. A series of terms are used to identify Chinese development finance, for example permutations of “China”, “development” and “export import bank” are used to identify potential hits. Names of borrowing countries are used to search in local language scripts, and for the CGEF Database, energy specific keywords in Chinese. After the web scrape, media sources of potential loans are aggregated into an interface to filter false positives using additional algorithms and keyword searches. For example, many articles on personal finance may contain relevant keywords, but are irrelevant. From there, all relevant new loan sources are added to each database for double verification, which is the use of at least two credible sources to confirm a loan signing.

In addition to using results from the web scraping algorithm, researchers use a source library of key host country government and ministry websites relevant to the loans and projects tracked. Energy or power-related ministry websites are included for energy-focused databases. Researchers systematically and manually check host country government ministries, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and official state-owned media in each country for potential new loans.

All loan transactions or projects are double verified with at least two credible sources to confirm that the loan was signed, the loan is public and publicly guaranteed, and that CDB or CHEXIM, and in some cases, other Chinese financiers were involved. Researchers strive to find at least one Chinese source and one external source, prioritizing government documents, embassies and official Chinese news like Xinhua, and company information like Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings, before turning to press and industry sources like RenewablesNow or HydroReview. As a final step, researchers archive sources online at a stable URL using the Internet Archive and store PDFs on an online repository.

The GCI database data collection method is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Data Collection Method

How do GCI databases compare to other databases tracking China’s OLDF and/or projects?

GCI databases only track public and publicly guaranteed loan commitments from Chinese lenders, primarily CDB and CHEXIM, by closely following the World Bank methodology on international debt statistics. This process is pursued to compare the development impacts of China’s OLDF with that of other DFIs, including the World Bank. The CODF Database also includes precise geolocation for its projects, and the CGP Database solely tracks Chinese-financed power plants. Databases elsewhere may track loans, grants, currency swaps, debt relief and/or investments to all entities within a country recipient, including private entities.

Does the GDP Center track other types of financial data from China, such as currency swaps, investment or grants?

The GDP Center tracks bilateral currency swaps through the Global Financial Safety Net (GFSN) Tracker. Generally, the GFSN is a set of institutions and financial instruments that countries can access to manage or mitigate short-term balance of payments and currency market stress. The GFSN Tracker covers international reserves, bilateral swap agreements, regional financial arrangements and loan agreements with the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Although the GDP Center does not directly track disaggregated investment agreements, projects supported by foreign direct investment from Chinese companies are tracked in the CGP Database. Additionally, in several policy briefs and the China-Latin America and the Caribbean Economic Bulletin, investment data is analyzed at an aggregated level and compared with development finance data.

The GDP Center does not track grants, as they fall in the category of aid that does not have to be repaid, which falls outside the scope of the transactions and projects tracked.

How can I download the data for each database?

Each database interactive has a section where users can fill out their contact information to receive an Excel file of the data. For the CODF Database, users can request access to a footprint map that provides a network view of projects by submitting a data use agreement (DUA). On each interactive website, click the ‘About/Data Download’ tab in the top right corner to access the form:

How can I learn more about the methodologies for each database?

The GDP Center regularly updates the Database Methodology Guidebook, which details the methodology and parameters used by researchers to construct the five databases tracking China’s OLDF and associated projects.

GCI databases are regularly updated on an annual or bi-annual basis (the CGP Database), to be as up to date as possible and regularly reflect the changing landscape of China’s OLDF. The GDP Center is open to feedback and seeks to enhance the accessibility and transparency of its data within the scope of the databases.

Feedback or questions? Reach out to Oyintarelado Moses, Data Analyst and Database Manager, odm@bu.edu.

*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global China Initiative Newsletter.