Webinar Summary – A Crisis of Confidence? Reestablishing the Legitimacy of the International Monetary Fund and the Global Financial Safety Net

On Tuesday, December 12th, the Boston University Global Development Policy Center (GDP Center) hosted a webinar titled, “A Crisis of Confidence? Reestablishing the Legitimacy of the International Monetary Fund and the Global Financial Safety Net.” The discussion covered quota reform at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the newly updated Global Financial Safety Net (GFSN) Tracker and building a fit-for-purpose financial system. William N. Kring, Executive Director of the GDP Center, moderated the event, and the panel consisted of Marilou Uy, Non-resident Senior Fellow at the GDP Center; Barbara Fritz, Professor at the Freie Universität Berlin; and Marina Zucker-Marques, Post-doctoral Researcher, SOAS, University of London.

In introducing the panel, Kring noted that the GFSN Tracker—co-produced by the GDP Center, the Freie Universität Berlin and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development—was recently updated with data through July 2023. It is the first interactive tracker of the GFSN, the set of institutions that provide insurance against crises and financing to mitigate their impacts. The GFSN has four main elements: countries’ own international reserves; bilateral swap arrangements whereby central banks exchange currencies to provide liquidity to banking systems; regional financial arrangements (RFAs) by which countries pool resources to leverage financing in a crisis; and the IMF. The latest data update underscores that the GFSN continues to be under-resourced and access to it is highly unequal. The IMF, with its broad and near-universal membership, is the so-called anchor of the GFSN, but its recently completed 16th General Review of Quotas made little progress towards increasing more equitable access to GFSN resources.

Fritz then provided an overview of key findings from the latest data update. Based around providing short-term finance to countries in need, the GFSN has expanded over time, first consisting of just the IMF, then encompassing new RFAs and then coming to include bilateral central bank currency swaps. The GFSN is now worth $3.5 trillion, but lower-middle income countries and upper-middle income countries are least covered as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). The IMF is the primary crisis financing mechanism for low- and middle-income countries, and Fritz recommended that the IMF provide more unconditional lending, coordinate more with other actors in the GFSN and receive a quota increase greater than the 50 percent increase provided by the 16th General Review.

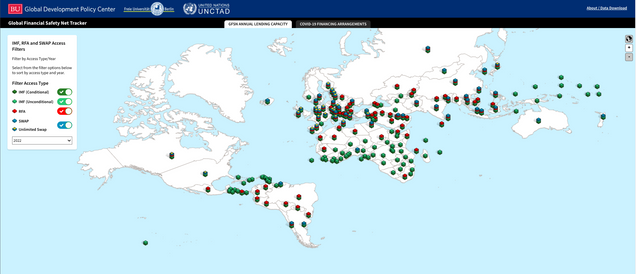

Next, Kring provided a demonstration of how to use the GFSN Tracker. The interactive map allows users to look at specific regions and countries. Users can filter by the type of liquidity arrangement: conditional IMF loans, unconditional IMF loans, RFAs, swaps and unlimited swaps. It also comprises two components in two separate tabs: the Annual Lending Capacity tab shows a country’s access limit to crisis finance in the GFSN, and the COVID-19 Finance Arrangements tab tracks COVID-19 financing arrangements, displaying the total amount of financing via loans from the IMF, RFAs and currency swaps in response to the pandemic.

Figure 1: Global Financial Safety Net Tracker – Annual Lending Capacity

Uy spoke next, focusing on the IMF’s 16th General Review, which officially concluded three days after the webinar. She said its 50 percent increase in quotas would reduce the IMF’s reliance on borrowed resources, but it represented a missed opportunity to realign quotas. The last quota realignment was agreed in 2010, entering into force in 2016, and in the meantime, a large gap has emerged between actual quota shares and how quotas would be distributed to countries if the IMF’s quota formula were applied based on current data. The 16th General Review did commit to adding a new Executive Board chair for zub-Saharan Africa and developing a new quota formula by 2025. Uy said that as IMF members work towards that deadline, they should consider giving greater weight to the GDP (adjusted by purchasing power parity) variable in the quota formula, remove the bias created by the existing openness and vulnerability variables, and members should come to a consensus on increasing the quota shares of emerging market and developing economies.

Zucker-Marques’ remarks focused on the role of China in the GFSN. China participates in all components of the GFSN: as an IMF member, as a member of RFAs like the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization (CMIM) and the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement, and as a provider of swap lines. About 40 percent of global swaps are provided by China, providing an important source of finance for developing countries. Zucker-Marques emphasized that swaps, which function like insurance, are different than development finance. Swaps provide short-term finance to improve financial stability, while development finance supports initiatives that aim to boost growth over the medium- to long-term.

In the Q&A portion of the discussion, questions focused on the reasons why access to crisis financing vary by income level as well as the potential emergence of alternatives to the IMF. Fritz noted that disparities in swaps and RFAs are a major driver in inequalities in the GFSN: while high-income countries can receive unlimited swaps and benefit from large regional funds, lower-income countries only benefit from small swaps and regional funds when available, and often do not benefit from them at all. Because these arrangements are driven by financial interests, high-income countries are typically seen as more financially important and have more ability to pool financing.

Uy argued that the GFSN reflects the interests of different countries. Countries typically resort first to RFAs and their more rapid financing, with the IMF serving the role of lender of last resort. Uy said that IMF members’ reluctance to increase the IMF’s quotas to a greater degree may be rooted in a belief that other actors were plugging gaps in the GFSN. Fritz underscored that the IMF should be aware that there is a diversity of arrangements in the GFSN, as highlighted by the GFSN Tracker. Zucker-Marques noted an increasing trend of South-South financial cooperation, and Kring pointed to significant capacity building taking place in RFAs.

In closing, Uy stated that lower-income countries need greater development finance in addition to more access to the GFSN. The high interest rate environment makes it difficult to attract financing. The IMF has also been a source of interest-free financing through its Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust, such that ensuring the financial sustainability of the Trust is also essential. She also pointed out that more Special Drawing Rights would boost countries’ reserves and improve the efficacy of the GFSN.

*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global Economic Governance Newsletter.