Chart of the Week: How the Global Financial Safety Net Differs in Capacity by Income Group

By Amanda Brown

Leaders from Group of 20 (G20) countries gather in Bali, Indonesia from November 16-17 – a highly anticipated policy event as developing countries face rocketing inflation, supply chain pressures from Russia’s war in Ukraine, the lingering financial bottlenecks of COVID-19 and devastating climate impacts. In the World Bank’s latest Global Economic Prospects report, research suggests that the developing countries will continue to struggle with economic growth beyond 2022 compared to the growth of advanced economies.

The Global Financial Safety Net (GFSN) – comprising the set of institutions, arrangements and agreements that provide temporary balance of payments finance to countries in financial distress – has increased its capacity after the Global Financial Crisis and in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, structural inequalities in the GFSN persist.

A recent policy brief from the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, Freie Universität Berlin and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development summarizes the updated findings of the Global Financial Safety Net Tracker, a public data interactive jointly compiled by the three institutions that quantifies the availability of crisis finance since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

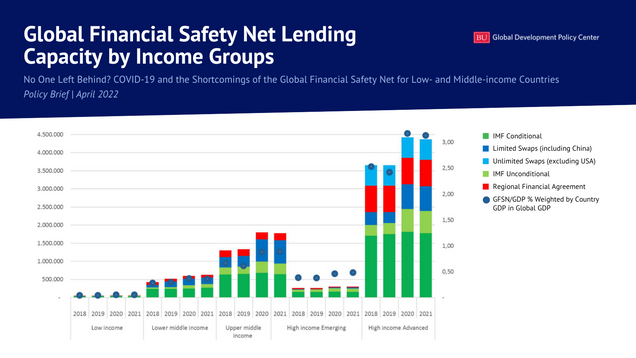

This Chart of the Week, Figure 2 from the policy brief, tracks the liquidity provision of the GFSN for countries grouped by income level.

Figure 1: Global Financial Safety New Lending Capacity by Income Groups

The chart reflects that while the GFSN has increased its lending capacity to address the COVID-19 pandemic, it falls short of providing equal choice and volume of crisis finance to each income group. Since the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, the accessible emergency finance volume remained low for low-income countries (LICs) and lower-middle income countries (MICs), while it increased for upper-MICs and for advanced higher-income countries (HICs).

LICs and some lower-MICs are systematically excluded from the most voluminous crisis finance elements, such as new regional funds or central bank currency swaps. LICs and lower-MICs also have temporary unconditional finance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) which are not comparable to the large pre-qualifying facilities that upper MICs have access to. The authors find that, ultimately, the GFSN does not allow support for all income country groups to respond adequately to a global liquidity crisis, exemplified by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Due to the current uneven and piecemeal setup of the GFSN, LICs and lower-MICs are in vulnerable positions and are further endangered by shocks like the COVID-19 crisis. While the IMF has taken steps to provide crisis finance with as little conditionality as possible, the lending capacity these facilities provide to LICs is small compared to the liquidity provision that HICs can request.

The authors of the policy brief make several policy recommendations, calling for greater emergency finance provision through coordination of GFSN elements to leverage their respective strengths, more options for unconditional balance of payments support and for multilateral institutions to become more attractive to member countries to prevent their marginalization and circumvention. They say addressing inequalities should be at the forefront of reforming the GFSN to most effectively respond to the ongoing global debt crisis.

Read the Policy Brief*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global Economic Governance Newsletter