Webinar Summary – The 2022 Paul Streeten Distinguished Lecture in Global Development Policy: The Future of Development Strategy

By Katie Gallogly-Swan

On Wednesday, March 23, the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, the Boston University Institute for Economic Development and the Boston University Department of Economics hosted the third Paul Streeten Distinguished Lecture in Global Development Policy.

The 2022 Distinguished Speaker was Dani Rodrik, renowned economist and Ford Foundation Professor of International Political Economy at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. Rodrik is an economist whose research revolves around globalization, economic growth and development and political economy. His lecture focused on the future of development strategy, wherein he explored what can be learned from recent economic development trends that challenge traditional understandings of structural transformation.

University Provost and Chief Academic Officer of Boston University, Jean Morrison, opened the event by welcoming guests, both in-person and virtual. She explained that the annual Paul Streeten Distinguished Lecture in Global Development Policy celebrates the example and legacy of Boston University Professor Paul Streeten as an eminent economist and interdisciplinary scholar.

Kevin Gallagher, Director of the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, then highlighted the legacy of Professor Streeten in the integration of development studies across Boston University’s schools and centers. He welcomed the 2022 Distinguished Speaker, identifying Rodrik’s own impressive legacy on development studies, noting that like the previous two Distinguished Streeten Speakers, Ann E. Harrison and Joseph E. Stiglitz, Rodrik’s work underscores the need for industrial policy in the process of economic development.

Rodrik began by recalling his own experiences with Streeten, indicating the influence of Streeten’s work on the evening’s lecture. The emphasis, in this regard, is the last word in the title of the lecture – strategy – which he claimed is not at the forefront of contemporary thinking on development. Rather, the focus has more narrowly been on the question of particular policy interventions and their effectiveness, or lack thereof. He highlighted that while this is important, there’s an older thinking in development economics of which Streeten was a part of, which addresses broader development strategy. In this approach, the focus is on the specifics of how economic development takes place. Rodrik outlined that his remarks would explore the future of development strategy, forewarning that while having some ideas of answers, he would primarily focus on what development strategy is unlikely to be.

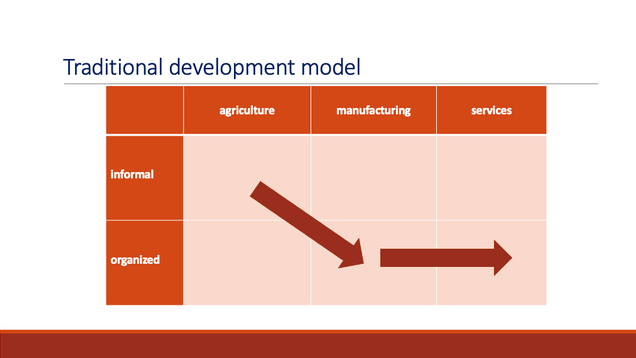

At the very basic level, development strategy is about overcoming the challenges of economic development through structural transformation. This means tackling dualism between islands of productivity amid poverty. The traditional understanding of achieving this transformation is moving workers from parts of the economy where productivity is very low and informality is high to more dynamic, modern parts of the economy, such as manufacturing and services. He noted that this is a challenge increasingly reappearing in advanced economies, including the United States.

What typically happens in the course of this industrialization is that relatively, unskilled less-educated, unproductive subsistence farmers move into urban areas to become higher-productivity, urban workers (the first arrow). After becoming a middle-income country, workers move into a higher productivity sector in services (the second arrow). Typically, the more rapid this transformation, the more rapid the growth.

Rodrik argued that what is happening today is very different from this traditional model of development. The movement of labor out of agriculture is still happening, but the actual employment absorption into manufacturing is much less rapid and much less visible. In fact, in low-income countries, the bulk of the workers that move into urban areas are moving into services. Most of these are informal, petty activities where productivity is not significantly higher than in traditional agriculture, meaning countries are not getting the economic benefits of technological upgrading. This triggers a process Rodrik has coined as ‘premature deindustrialization’, where low- and middle-income countries move away from manufacturing at a much faster pace.

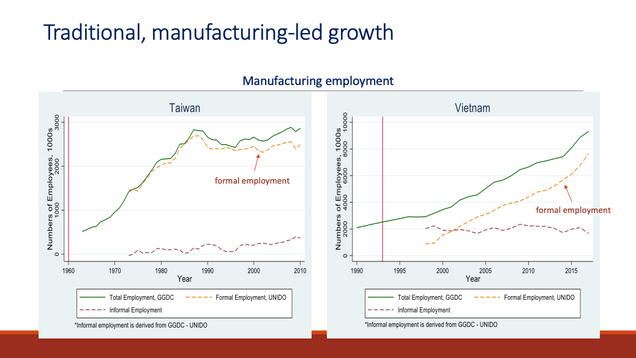

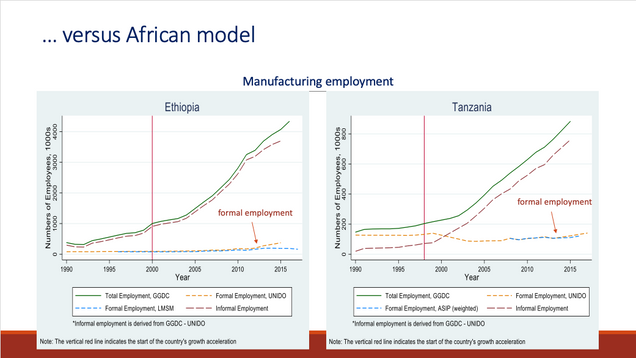

Rodrik went on to compare historical economic development in East Asia with contemporary economic development in industrializing countries. In the Vietnamese and Taiwanese examples, the formal component of employment tracks the very rapid rise in employment, whereas in Ethiopia and Tanzania, new employment instead tracks with the informal economy while formal employment has remained flat. Taking a closer look, Rodrik finds that productivity in these informal firms in manufacturing has been essentially stagnant. This indicates increasing dualism within manufacturing: big firms are highly productive and successful and small informal firms have poor productivity, and the latter is where all new employment is going.

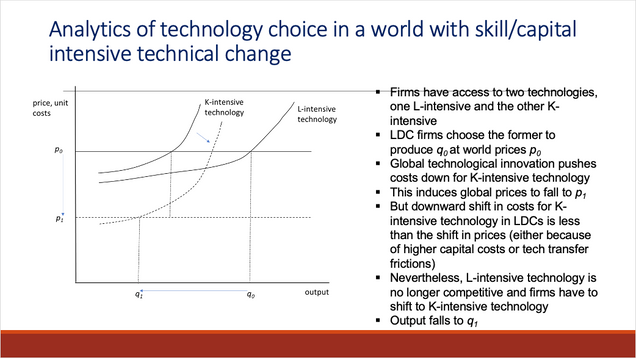

While it is puzzling to understand the full picture of why this is happening, one theory Rodrik is working on with colleagues focuses on the nature of modern technology. The large, high productivity firms in Ethiopia are using capital-intensive technologies that are typical in much richer countries. This indicates these countries are borrowing unsuitable technologies to become more productive and therefore more competitive in global markets, but this creates a dilemma whereby these firms cannot absorb labor at high levels. This is the same reason that very capital-intensive technology sectors in advanced economies are not absorbing a lot of labor but are in fact losing workers, highlighting that this trend is driven by something that has nothing to do with what’s happening in individual countries.

Normally, lower-income, developing countries would choose labor-intensive industries due to their comparative advantage of cheap labor, but as high-productivity, automated technologies become cheaper, they are forced to adapt to remain competitive. Unfortunately, adopting these capital-intensive technologies is less profitable for low-income countries, whether because of tech transfer frictions or higher capital costs.

Rodrik also pointed out that in protected segments of the economy not faced with import competition, labor intensive technology continues, but these industries are not likely to be globally competitive. Since this is where the bulk of labor is moving in modern industrialization, there is a “triple whammy” on employment: a direct employment loss due to reduction in output, an additional employment loss due to shift in technique and a reduction in employment elasticity to positive profitability shocks. Rodrik made the case that this amounts to a bias against the comparative advantage of developing countries where low skill labor is abundant, making industrialization much less effective as a vehicle for economic growth.

This poses a question: what is an alternative development strategy that can deliver growth and structural transformation? To answer this question, Rodrik argued that it’s essential to understand what made manufacturing special, which boils down to three things: productivity dynamics that straightforwardly led to unconditional convergence, absorption capacity of a reserve army of low-skill workers and basically unlimited demand through global trade.

As the second feature is no longer true, Rodrik asserted that manufacturing no longer works as a development strategy. Rather, he posed potential alternatives in agriculture and services.

Increases in agricultural productivity can support significant growth, but there is a challenge for this sector to absorb high levels of labor since it faces the same technological upgrading challenge as manufacturing. With services, there are broadly two types: the high-productivity, tradable segment and low-productivity, non-tradable. The former also faces labor-absorption challenges, while the latter are unlikely to generate growth as a consequence of being un-tradeable. A clear dilemma emerges, highlighting the difficulty for developing countries today to benefit from the kind of growth rates that successfully industrializing countries managed to achieve in the past.

According to Rodrik, any development strategy of the future will need to focus on creating better jobs in firms that can absorb more workers – the ‘good jobs’ model. These segments are unlikely to be the large-scale exporters or the most tradable parts of the economy, but instead will be services and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). This will not lead to Chinese or South Korean rates of growth, but has the greatest potential of achieving both economic development and inclusion.

The East Asian industrial policy model is the most common understanding of successful economic development, but according to Rodrik, some of the most prosperous recent industrial policy doesn’t really operate in this kind of ex-ante, top-down sort of government, where there’s a strong disciplining of firms. It has become much more collaborative and iterative, starting out with open-ended goals rather than clear targets. For the challenge at hand, Rodrik suggests that more customized approaches with soft conditionality on job creation, and a focus on SMEs is more likely to support labor absorption than traditional subsidies and tax incentives for export champions. This is necessary in a variety of settings and governance levels including localities and municipalities, considering the focus is on supporting hundreds of smaller firms, rather than a few large ones.

Rodrik pointed to a few critical strengths of this ‘good jobs’ agenda. Firstly, that it targets the productive structure directly rather than providing people with cash grants or general-purpose education and hoping that it will produce employment down the line. Secondly, it breaks through institutional fetishism, encouraging an ongoing iteration and collaboration between state agencies and firms or private sector, so the traditional distinction of markets versus state no longer applies. Thirdly, by directly targeting the productive forces in the economy, equity and inclusion strategies are merged with the growth strategy, becoming one and the same.

Following the lecture, Dilip Mookherjee, Director of the Boston University Institute for Economic Development and Professor of Economics, joined Rodrik on stage to discuss questions from the audience. The discussion explored the role of development banks in development strategies, insights regarding middle-income countries, regionalization, migration, job-creation strategies in Africa, the role of climate change technology, direct investment strategies and the relevance of this approach in advanced economies.

Explore the full slide deck:

*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global Economic Governance Initiative newsletter.