How the International Trade and Investment Regime Constrains Pandemic Policymaking – And What Global Leaders Can Do About It

As COVID-19 has taken millions of lives, governments around the globe have attempted to quickly mobilize and mitigate the health, social and economic impacts of the pandemic. Pandemic-responsive policy interventions ranging from subsidies to trade restrictions, and investment measures to government procurement initiatives, have taken precedence over traditional policy preferences that would favor market-oriented approaches over government regulation.

At the same time, these emergency measures appear to contravene trade and investment rules embodied in World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements and elsewhere. This reality is especially poignant, as the WTO announced for the second time the indefinite postponement of the 12th WTO Ministerial Conference (MC12), in which leaders were set to negotiate reform and discuss expanding the rule-making function of the organization. While some countries hoped to introduce new disciplines in investment, services regulation, fisheries subsidies and more, others had looked to the WTO to increase equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines and produce a development-friendly response to climate change.

The health and economic responses to the pandemic precipitate a reflection on the appropriate role and priorities of trade and investment rules in governing international economic activity. During the pandemic, most in the global community would agree national public welfare took precedence over trade rules, to the extent that they were in conflict. Nevertheless, pandemic-related policy interventions reflect several tensions and tradeoffs, namely between national and global health needs; between private interests in profits and expansion of market share and public interests in broad-based access to diagnostics, treatment and vaccines and between the need for efficiency in manufacturing and equitable distribution of those COVID-19 products.

A new report from the Working Group on Trade Treaties and Access to Medicines at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center investigates the relationship between the trade and investment rules and government policy responses by a sample group of six large countries: the United States, Germany, France, China, South Africa and India. The research seeks to test whether the current rules, had they not been ignored or violated, would have constrained the policy space in which governments were operating and whether the policy interventions carry risk of legal challenge in international tribunals.

Trouble ahead

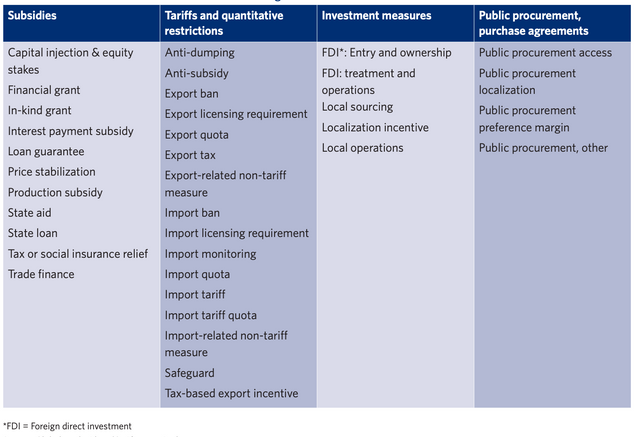

The countries studied were quite active in implementing a wide variety of policies to mitigate the impacts of the pandemic – from subsidies and trade restrictions, to different types of investment measures and government procurement initiatives. Although the diversity of measures is quite large, we grouped them into four general policy categories to demonstrate how they are governed by, and often constrained by, the global trade rules, as shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Government Intervention in Four Broad Categories

Subsidies were the most common policy tool deployed, taking various forms including state aid, loans, loan guarantees and trade finance. All the countries in our study utilized trade measures, especially export restrictions to retain production of essential COVID-19-related products. In overall terms, the US implemented the most interventions, China the fewest and India the most diverse. Importantly, China, South Africa and India relied more heavily on tariffs and quantitative restrictions than on subsidies, in part due to fiscal resource constraints.

A review of WTO and other trade agreement rules reveals these policies enacted during the global pandemic are not likely to immediately run afoul, as the trade agreements all generally retain emergency- or necessity-based exceptions and carve-outs for extreme circumstances.

Concomitantly, it is clear that the countries studied (and those beyond) avoided some policies due to logistical challenges and legal uncertainty. The best example of this are compulsory licenses (CLs) for patented COVID-19 products. CLs allow governments to extend licenses to domestic producers in the absence of permission from the patent holder in the case of a national or global emergency. This process, however, is challenging in the best of times, as it requires the granting country to have a domestic system in place that meets high standards of notification, transparency and judicial review set out in the WTO’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). This process would be exponentially more complex for COVID-19 vaccines, as each is covered by multiple patents, requiring a network of licenses. Moreover, countries without manufacturing capacity would have to rely on a secondary licensing process to import the products, exacerbating the intricacy of the process. Finally, many countries that have attempted to grant CLs in the past have been met with resistance by dominant pharmaceutical-producing countries, discouraging future attempts.

Even policies permitted as a legitimate response to the global emergency may conflict with the rules once the pandemic is declared “over” in the US and Europe. Subsidies offered to the pharmaceutical sector will need to be phased out, trade restrictions eliminated and all elements of discrimination in favor of a government’s national firms will need to be scrubbed from their regulations. If countries do not successfully transition away from these government interventions in a timely manner, they are likely to be challenged before a WTO panel or other international tribunal, the defense and outcome of which could put additional strain on an already fiscally strapped developing country economy.

Towards a more flexible trade regime

There are tensions and trade-offs in this policymaking world. National policies typically prioritize their own populations, often at the expense of vulnerable people elsewhere and wealthier countries have greater access to the tools necessary for fighting the pandemic. Public sector efforts to increase the production and distribution of essential products often confront resistance from private firms that seek to maximize profits. The disquieting result is widespread inequity, with just 6 percent of the African continent being vaccinated, while the US offers vaccines to young children and booster shots to adults.

To meet the needs of vulnerable countries and individuals, therefore, the report proposes three levels of policy recommendations.

In the immediate term, global leadership must push ever more urgently to end of the pandemic through equitable and effective distribution of vaccines and treatments. This will involve WTO members negotiating and agreeing to a waiver of key provisions of the TRIPS Agreement, high-income countries (like the US and Germany) fostering technology and know-how transfer for low- and middle-income country producers, as well as financing, and international organizations, like the World Health Organization, providing support.

Second, the international community must consider the longer-term implications of this pandemic, namely reforming the WTO to allow low- and middle-income countries to build resilience for future pandemics. At the eventual MC12, this means backing away from new rules in investment protection and domestic regulation and allowing existing rules and flexibilities to encourage more equitable distribution of essential goods. WTO members should also advocate for preserving and expanding policy space to build and sustain health sectors within countries, as India and South Africa continue to do. That flexibility should enable regional country groups to collaborate in building accountable regional production hubs, and low-and middle-income countries to take an active role in their health sector development.

Third, in addition to uncovering health vulnerabilities worldwide, the pandemic revealed underlying economic inequities that exacerbate those vulnerabilities. As such, WTO members must recognize the primacy of public welfare goals generally, including health, environmental and development goals. This may take the form of scaling back new rules and commitments, or expanding the special circumstances that give rise to exceptions under the agreements.

When trade ministers eventually gather for MC12, they will face the question: is the current international trade and investment regime helping or hindering member countries as they respond to global crises, both today and in the future? Rather than bind policymakers’ hands, the WTO should recognize that government actions to protect human well-being, achieve greater social equity and protect the planet are of the highest order priority.

Read the Report