Ibram Kendi, Joel Christian Gill Team up for New Graphic Version of Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning

Ibram Kendi, Joel Christian Gill Team up for New Graphic Version of Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning

Collaboration offers a graphic history of American racism, intended for a broader readership

This article was first published in BU Today on June 5, 2023. By Rich Barlow. Photos by Cydney Scott

Excerpt

“Any concept that regards one racial group as inferior or superior to another racial group in any way.” That succinct definition of racist ideas undergirded Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped From the Beginning, his National Book Award-winning history of US racism. By that metric, Kendi, founding director of BU’s Center for Antiracist Research, indicted some surprising historical figures, white and Black, for racist thoughts, among them abolitionists William Loyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass, NAACP co-founder W.E.B. Du Bois, and former US president Barack Obama.

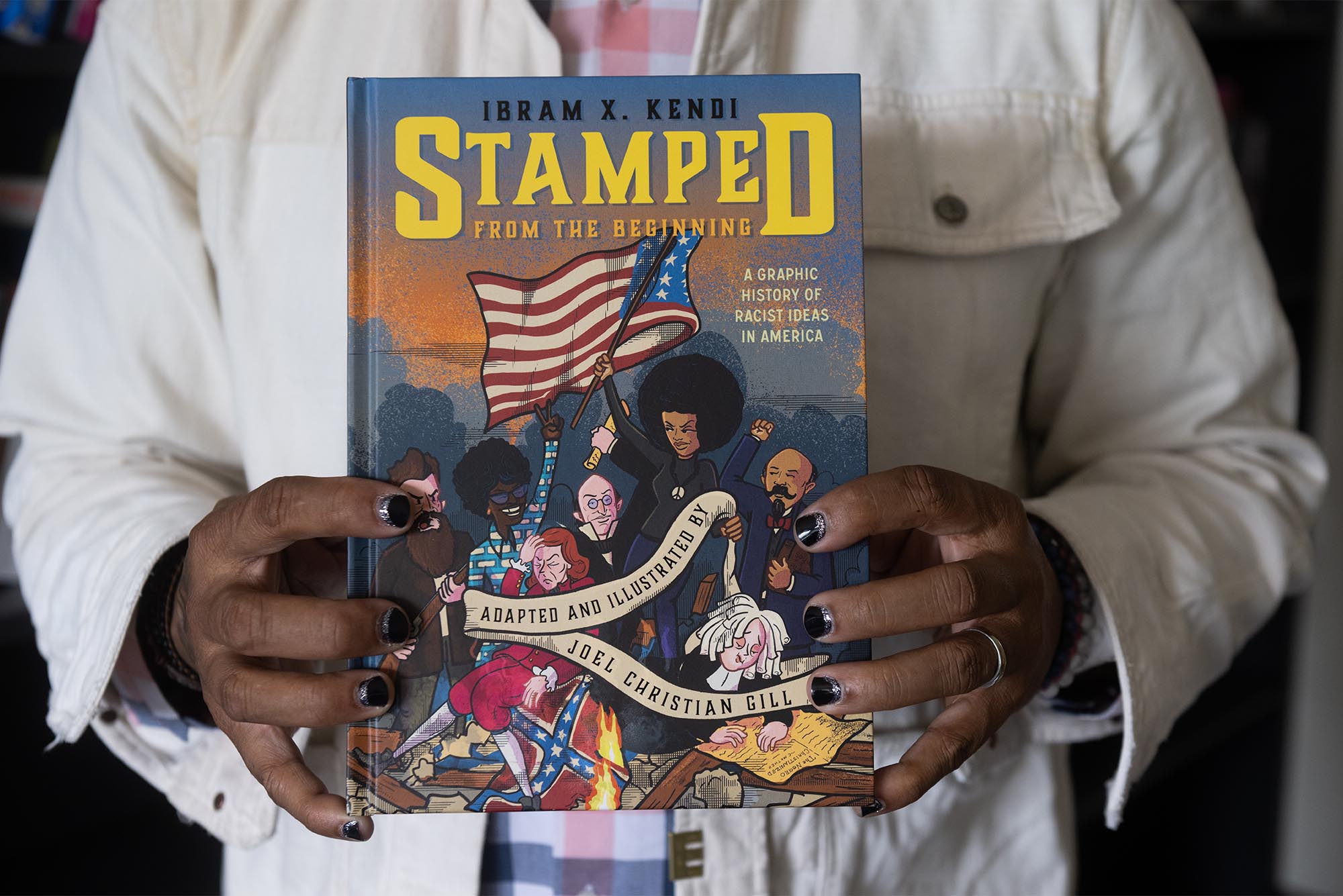

Kendi and BU colleague Joel Christian Gill (CFA’04) have collaborated on a new, graphic version of Stamped, out June 6 from Ten Speed Press. Gill, associate professor of art at the College of Fine Arts and chair of its new master’s program in visual narrative, illustrated the volume and added modern idioms, abbreviations (“IDK”), and even humor.

Among the racist ideas that even civil rights heroes harbored, Stamped says, were assimilation—Black culture is inferior but can be bettered if African Americans assimilate into “traits held in esteem by the dominant White Americans.” Another is uplift suasion, the idea that Black Americans can purge white racism by working hard and succeeding. Not only does that put the burden of eliminating racism on its targets, the book says, but it has never worked: white people dismiss upwardly mobile Black people as exceptional, “Extraordinary Negroes.”

BU Today spoke with both men about their book. The interview was edited for clarity and brevity.

Q&A

WITH JOEL CHRISTIAN GILL AND IBRAM X. KENDI

BU Today: Professor Gill illustrated the book; how did you divide prose duties?

Gill: I’d just like to thank Doctor Kendi for letting me put fart jokes in his history tome.

Doctor Kendi gave me a pdf with highlighted sections to focus on. I built a narrative around those sections. I added stuff like “IDK” and “are you mansplaining” after the fact. Trying to make something as serious as racism and the history of racist ideas in America funny is difficult. I feel most of the jokes are funny-not funny.

Professor Kendi, is that what you were expecting, and why did you want to do a graphic version of Stamped?

Kendi: I didn’t fully know what to expect, but I did know that Joel was not only a great comic artist, but also an historian in his own right. I suspected that whatever he produced would be great visually and conceptually. I thought it was important to help create a graphic history specifically, because I’ve been long trying to think of new ways to make this history of anti-Black, racist ideas accessible to different types of readers. There are some readers who will read this graphic [version], but they won’t necessarily read a 500-page narrative history. I don’t feel any ill way about that, so long as they’re reading and learning.

Those who’ve read neither version of Stamped will be surprised at some people, white and Black, who you say promulgated racist ideas. To take one example, can you discuss Barack Obama?

Kendi: Since the 1960s, there have been a number of theories that have been put forth as to why Black people remain on the lower end of disparities. One of the more prominent theories is this idea that oppression itself has led to Black people feeling hopeless and therefore not striving as much. This is a theory put forth by many thinkers, including Barack Obama. Similarly, previous thinkers had stated that Jim Crow or segregation led to deficient Black behavior, or slavery literally imbruted Black people. It’s what I call in my work the oppression inferiority thesis: that the oppression led to inferior behaviors. But there’s no evidence that supports that idea.

Gill: That’s what happens when you live in a society where you’re inundated with these ideas. They become these things that you ultimately just believe as facts. I remember being on a plane and listening to hip-hop from the 90s. I remember really loving some of these songs—conscious hip-hop, hip-hop that was pro-Black and empowering. Listening to them now, it’s all respectability politics [the belief that conforming to white standards will shield Black people from racism].

People get upset at the idea, when [told] you have racist ideas, that it’s an insult. But it’s not—it’s an adjective, and it’s an adjective that can be changed. So to say that President Obama has, at some point, said something [racist] is not an indictment of the president. It’s an indictment of a system that inundates us with these ideas over and over and over again, until we believe these things. The difference between Black people and white people, the genetic difference, is a rounding error. And we have applied so much cultural significance to that rounding error.

White people were a created social construct that was defined to be in power. That being the default for society means that everybody at some point is going to say something that’s going to be deemed racist. We live in a society that’s inundating us with those ideas, so it’s hard to work against it. And we have to work against it.

Professor Kendi told Stephen Colbert that white parents who fear that teaching antiracism will shame schoolchildren should encourage their kids to identify with white abolitionists. Do any such figures stand out to you both in Stamped?

Gill: John Brown [the abolitionist executed for raiding a federal armory to incite a rebellion by enslaved people before the Civil War] is someone we should be building statues to. History has shown him to be right.

Kendi: One person I’d point to is one of the first white abolitionists, John Woolman. He was a Quaker, and in the mid-1700s, he wrote one pamphlet in which he challenged slavery but also imagined that there was something wrong with Black people. He subsequently visited plantations and ultimately came out with a second pamphlet, in which he almost renounced those earlier ideas, and talked about [how] the notions of white superiority and Black inferiority are wrong, too, and how that reinforces slavery. It is important to point out people in history who have the capacity to change and transform their ideas and recognize when they were wrong.