BU Faculty Combine Academics and Activism—with Social Justice at the Core

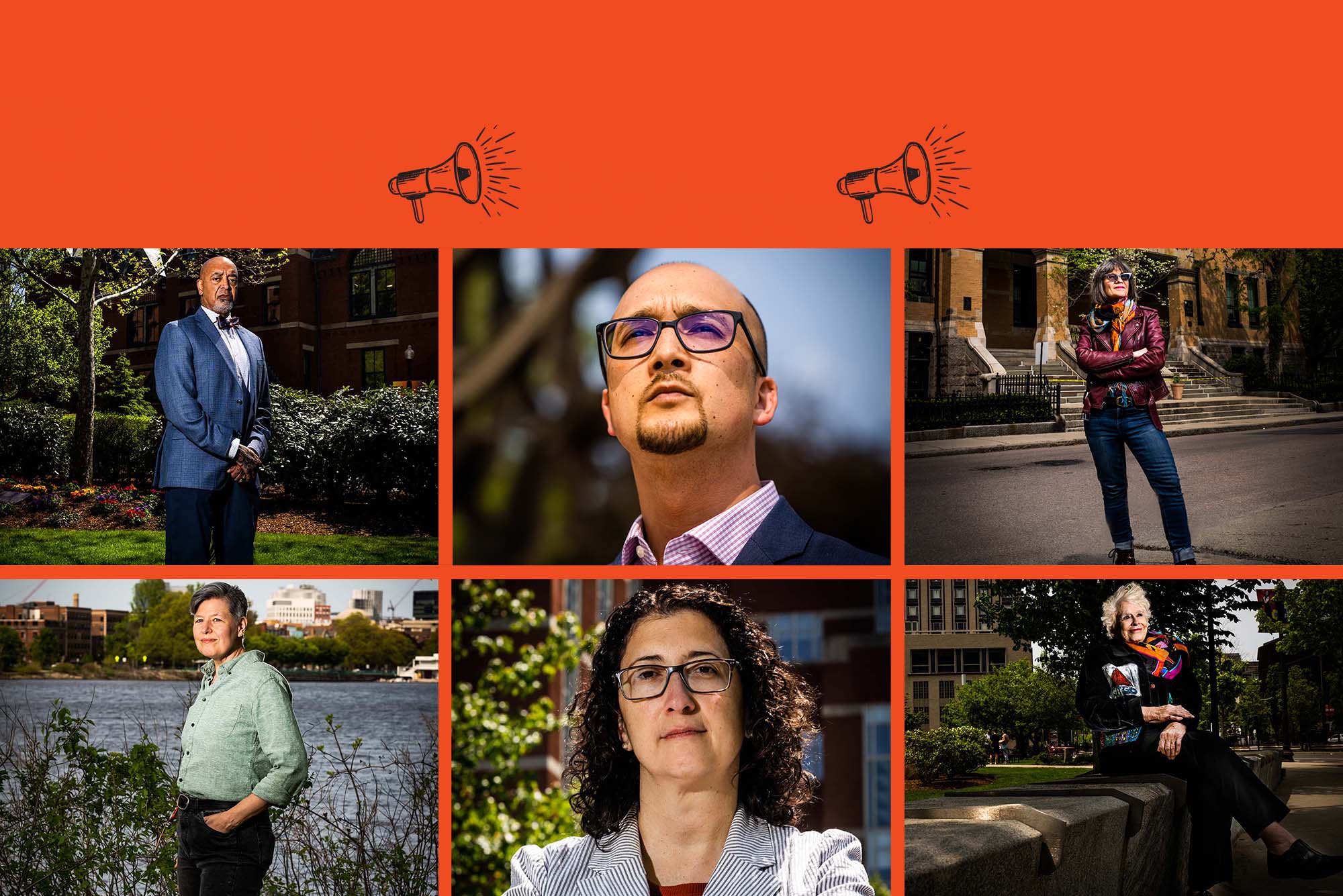

Craig Andrade, a School of Public Health associate dean of practice and coleader of the Activist Lab (top row, from left); James McCarty, a School of Theology assistant clinical professor of religion and conflict transformation; Dawn Belkin Martinez, a School of Social Work clinical professor and associate dean for equity and inclusion; (bottom row, from left) Karen Warkentin, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of biology and of women’s, gender, and sexuality studies; Katharine White, a BU Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology; and Caryl Rivers, a College of Communication professor of journalism.

BU Faculty Combine Academics and Activism—with Social Justice at the Core

Some professors risk criticism, physical discomfort, even arrest, as they take a stand on issues important to them

On his final day teaching at Boston University in 1988, historian and author Howard Zinn ended class early to support a strike at what was then BU’s School of Nursing. It was a characteristic last act for the political activist and College of Arts & Sciences professor emeritus of political science, who often took his lessons outside the classroom and into the streets, leading or participating in protests, sit-ins, teach-ins, and rallies, and who spoke out fiercely against societal injustices.

From marching for civil rights, leading anti-war protests, supporting workers’ rights, and lifting up those who have been underrepresented in textbooks with his 1980s bestseller, A People’s History of the United States, Zinn, who died in 2010, has had a lasting legacy at the University—one that’s carried on by current faculty activists fighting to make the world a better place. For them, social justice is often at the core of their activism.

Activism at BU crosses a range of disciplines, from journalism to medicine, biology to law, education to fine arts, humanities to engineering. For example, public health and activism often go hand in hand, since one of the field’s pillars is to improve the health and well-being of people and communities—particularly the underserved—by helping to set safety protocols in workplaces and creating campaigns that educate the public on vaccines or smoking cessation. Activism takes many forms—making and teaching art, gathering for political rallies, and influencing lawmakers, to name a few.

“The word activist raises all kinds of images of people on a march or with megaphones and big placards,” says Craig Andrade, associate dean of practice at the School of Public Health, who leads the Activist Lab along with David Jernigan, an SPH professor of health law, policy, and management. “But there is a spectrum of ways for people, from extroverts to introverts, to contribute to activism. We know in history there were people out front at the microphone, and people making the plans for next steps in a particular movement. All of us have a way to contribute to change that is ever more important for our democracy and for humanity.”

These faculty are not afraid to risk criticism, physical discomfort, even arrest, as they take a stand on issues that are often deeply personal. For many, like Zinn, social justice is a calling that has become inextricably linked with their academic lives.

“MY MORAL COMPASS”

“It is a far more activist campus than it was when I came,” says Caryl Rivers, a College of Communication professor of journalism, who joined the faculty as an adjunct professor in 1970 and is the author of more than 20 books on gender, race, politics, and feminism. Rivers and Zinn went down in University history as part of the “BU 5”—a group of professors who, in 1979, refused to cross a picket line until the University’s librarian union agreement was settled, escalating a clash with then-President John Silber (Hon.’95), who wanted them fired. Their actions and the strikes received local and national attention, and Silber eventually backed down.

“I think that set a precedent: that faculty and students weren’t just going to accept the dictates of the president,” Rivers says. In the years following, she continued to write about politics, the feminist movement, and conservatism under President Ronald Reagan, at times pushing the boundaries of what was acceptable in mainstream media. She was once assigned a story by the New York Times on soldiers returning from the Vietnam War, which the paper then rejected for being “too angry,” Rivers says. “I said, ‘There’s not one emotion of mine in there. All the anger is coming from the veterans who I interviewed.’” The story was later published in the political magazine The Nation.

These days, you can find faculty at BU schools and colleges whose roles in academics and activism are tightly intertwined. Dawn Belkin Martinez, a clinical professor and associate dean for equity and inclusion at the School of Social Work, is one of them. In 1985, she was among the 550 people to stage a sit-in at a federal building in Boston to protest the Reagan administration’s involvement in Nicaragua.

“We occupied the building, saying we’re not going to leave until our demands are met,” she says. (The group was arrested, but the charges were eventually dropped.)

During the 1980s, Belkin Martinez also participated in the city’s housing justice movement while a senior social worker at Boston Children’s Hospital inpatient psychiatry service. She was a part of the successful effort, led by nonprofit organization City Life/Vida Urbana, to prevent the former Bowditch School in Jamaica Plain from becoming luxury condos. They took over the parking lot and camped there for a week.

“Change happens when people organize,” Belkin Martinez says.

While working at Children’s Hospital, she cofounded Boston Liberation Health group and developed the Liberation Health Model of Assessment and Intervention, a health assessment tool for social workers to use with clients. The model gives individuals and families a way to understand how personal problems are tied to institutional factors, such as racism, wages, political issues, and historical conditions, and gives them tools to liberate themselves from internal and external oppression.

“Making the world a better place and trying to change all of the structural inequities that have a direct impact on the people social workers serve is my North Star, my moral compass,” Belkin Martinez says. “I think the role of a teacher is to show stories that counter the dominant worldview, like how City Life/Vida Urbana got the Bowditch School back. When you bring those stories to light—like what Howard Zinn’s A People’s History did—people feel inspired, and it gives me hope that there’s the possibility of another world.”

WHEN SCIENCE AND ACTIVISM COLLIDE

For Karen Warkentin, a CAS professor of biology and of women’s, gender, and sexuality studies, activism has been a lifelong pursuit. But in Warkentin’s early years at BU, they felt the need to quiet their activism surrounding their queer identity and to focus instead on their science and tenure.

“When I started here, certain perspectives were not welcomed,” Warkentin says. A case in point, they recall: the University’s Gay-Straight Alliance at BU Academy was banned not long after they joined the BU faculty, in 2001. “As far as I knew, I was the only queer professor in biology, and the only queer science professor that I knew—which doesn’t mean that I was the only one, but there was no visibility,” Warkentin says.

That began to change in the early 2000s, as the culture shifted and LGBTQ+ rights were more prominent and then-BU President Aram Chobanian (Hon.’06) added sexual orientation to the University’s nondiscrimination policy. In 2018, Warkentin became cochair of BU’s LGBTQIA+ Faculty and Staff Task Force. Assembled to make the University more welcoming to all genders and sexual identities, the task force called for expanding employee benefits to same-sex partnerships and creating more gender-neutral facilities, among other changes.

The group’s biggest ask was for the University to establish a professionally managed center with resources, programming, and community for LGBTQIA+ faculty and staff. The center opened in 2022.

These changes don’t just benefit the University. They’re good for science, Warkentin says: “Representation and visibility are really important for our young people. That has been a motivator for me in terms of being out and speaking up. You can call it activism or just good science, but we need people with different backgrounds and perspectives to find and ask questions. We often think about bias in interpretation of results, but if we don’t ask a question in the first place, we’re never going to get to that stage.”

“Representation and visibility are really important for our young people. That has been a motivator for me in terms of being out and speaking up.”

For some professors, their field of study fuels their activism. Nathan Phillips, a CAS professor of Earth and environment and a vocal climate activist, arrived at BU in 2000. In 2013, the student-led divestment movement was in full swing amid a nationwide call for universities to pull their financial holdings from the fossil fuel industry. The efforts proved successful, and in 2021, BU announced plans to start divesting immediately.

“They motivated me to think about which side I was going to be on, since I teach about climate change, ecology, and carbon budgets,” Phillips says, referring to his students.

Phillips is a tree physiologist who has spent the past decade researching the effects of leaking natural gas pipelines on urban trees and air quality. The pipelines leak methane, a potent greenhouse gas that accelerates climate change and can impact human health. And a gas leak that kills an urban tree leaves local residents in a heat island with reduced air quality, Phillips says. “That’s an injustice,” he says. “I couldn’t compartmentalize that into a different place.”

Much of his activism today is rooted in the fight against our continued reliance on fossil fuels, like coal and gas, and outdated fossil fuel infrastructure, such as natural gas pipelines.

Phillips has participated in numerous acts of nonviolent civil disobedience and peaceful protests. As part of the No Coal, No Gas campaign, in December 2022, he and another protester locked themselves to the train tracks in Westford, Mass., to stop a train carrying coal through Massachusetts to New Hampshire. They halted the train for more than three hours.

Phillips has been arrested nearly a dozen times over the years, most resulting in fines and short jail stays. The first time was in 2016, when he and fellow protesters hopped into an open trench where a high-pressure pipeline was being laid in West Roxbury, Mass. They had written letters to legislators, met with local officials, and submitted letters to newspaper editors. None of it worked. “At some point we put our bodies in the way to stop the unchallenged injustice,” he says. More than 150 people were arrested over the weeks of active demonstrations against the pipeline; the charges were later dropped.

These were not the only instances of Phillips putting his body on the line. Inspired by the hunger strike of Yosef Abramowitz (CAS’86)—a protégé of Zinn’s who protested BU’s investments in South Africa during apartheid in the 1980s—Phillips carried out a hunger strike in 2019 to oppose the public health hazards of a natural gas compressor that was planned in North Weymouth, Mass. (Compressor stations help keep the gas flowing as it’s transported across long distances.) His hunger strike lasted 14 days. Despite strong opposition from the local communities, the compressor started operating in 2020.

“I often get asked about the hunger strike: Did you win? Was it worth it? Did you stop the compressor?” he says. “On one level, the answer is no—the compressor is built and running. But I do not at all regret what I did and how it deepened my connection with the community there.” That fight continues, according to Fore River Residents Against the Compressor Station, a community Phillips still works with. They recently sent a letter to Governor Maura Healey, with requests such as completing a full Environmental Impact Statement and Health Impact Assessment of the compressor.

Fighting for justice has brought meaning and connection to Phillips’ life, he says, just as his research has.

WHEN THE JOB IS ACTIVISM

James McCarty, a School of Theology assistant clinical professor of religion and conflict transformation, has also spent years building relationships with local communities. The director of the Tom Porter Program on Religion & Conflict Transformation, McCarty is a restorative justice, transformative justice, and conflict transformation practitioner and researcher—that is, he works with people and organizations to repair harms caused by racism, violence, and oppression.

As a Korean American, McCarty has always felt a commitment to racial justice. In 2014, he started as a chaplain at Seattle University. Not long after, Eric Garner was killed by a New York City police officer, and the Black Lives Matter movement gained national attention. In response, he and a colleague organized a die-in on the Seattle University campus.

“This country is really broken,” says McCarty. “And one of the ways that it’s really broken is along lines of racial injustice and oppression.”

He joined local communities in Tacoma, Wash., to help combat increased violence among young men of color. They agreed that the best response would be to implement peacemaking circles, a restorative justice practice inspired by indigenous traditions that offers alternative ways to respond to crime. The circles brought together people who have caused and experienced harm in an attempt to build empathy, bring about healing, and prevent offenses.

“The way my life played out, with the communities that I’m connected to, [my work] turned radically local,” McCarty says. “And that’s just because I’ve really spent the time listening and building relationships.”

McCarty arrived at BU in August 2022. He hopes to continue building relationships here, with people engaged in transformative justice and restorative justice, such as the local nonprofit Communities for Restorative Justice and other grassroots groups.

On the Medical Campus, Katharine White was using her platform as a doctor to advocate for patients’ reproduction rights and abortion access in Massachusetts long before the US Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022. White is a BU Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology and a clinician at Boston Medical Center, the University’s primary teaching hospital. In 2017, she gave oral testimony in support of the Massachusetts ACCESS law, which lowers the cost of contraception for people who are eligible, and provided written testimony for the ROE Act, which expands access to abortion in the commonwealth.

When Roe v. Wade was overturned, White, who also is associate director of the Complex Family Planning Fellowship at BU, was ready to double down on her advocacy and research to improve reproductive healthcare.

“There is a 400-year history of reproductive coercion in the United States going back to the time of slavery,” White says. “Our country has not always valued every pregnancy and every birth.” She says that the healthcare systems in place still don’t equally value people based on race and gender—research has shown that losing the legal rights to reproductive care disproportionately impacts women and families of color.

“I’m grabbing every opportunity to shout from the rooftops about how devastating this decision is for the health of people who can become pregnant,” White says of the high court’s decision. “It affects all reproductive health, like ectopic pregnancies, miscarriages, contraception, infertility care. In a country with unconscionably high maternal mortality rates, taking away abortion care is literally sentencing women to death.”

“In a country with unconscionably high maternal mortality rates, taking away abortion care is literally sentencing women to death.”

White has a grant from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health to evaluate a new approach to speaking with patients about contraception that is centered on empowering an individual to make decisions based on their unique needs and preferences.

Through her research, and by regularly talking to the media, White hopes to continue empowering people to have a better understanding of their body—which was also the motivation behind her two books, Your Guide to Miscarriage and Pregnancy Loss (Mayo Clinic Press, 2021) and Your Sexual Health: A Guide to Understanding, Loving and Caring for Your Body (Mayo Clinic Press, 2022). “Some doctors, especially young doctors, hesitate to become advocates because they’re afraid of how their voice is going to be heard,” White says. “But no one can take away your patient experiences, your lived experience. As a doctor, you are the expert in a room and you advocate for patients all the time already. Your voice really matters.”

SELF-CARE IS ESSENTIAL

At the Activist Lab, Andrade’s team has launched a program that connects SPH students with more seasoned public health practitioners and has awarded micro grants that fund student-led projects. Past awardees have used the money to survey needs for gender-affirming care, start a literacy program for people experiencing homelessness, and measure lead levels in soil.

Andrade also teaches Strategies for Public Health Advocacy, a course that covers persuasive advocacy, such as creating a concise elevator pitch for a legislator, writing an op-ed piece, and effectively communicating with the public. Given the scope of the work, he likes to remind his students that, with so much to be done—particularly at a time when some lawmakers are trying to undermine public health efforts and limit education on sex, gender, and race, he says—self-care is an essential part of any type of activism.

“We have to care for ourselves, and I speak about this often and bring this to my coursework,” Andrade says. “How do we take care of our inner self, our spirit, our mental health in a way that allows us to stay in the moment and tap into our inner strength? How can we persist?”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.