POV: It’s Time to Upgrade to Ungrading

Photo by iStock/paulw11

POV: It’s Time to Upgrade to Ungrading

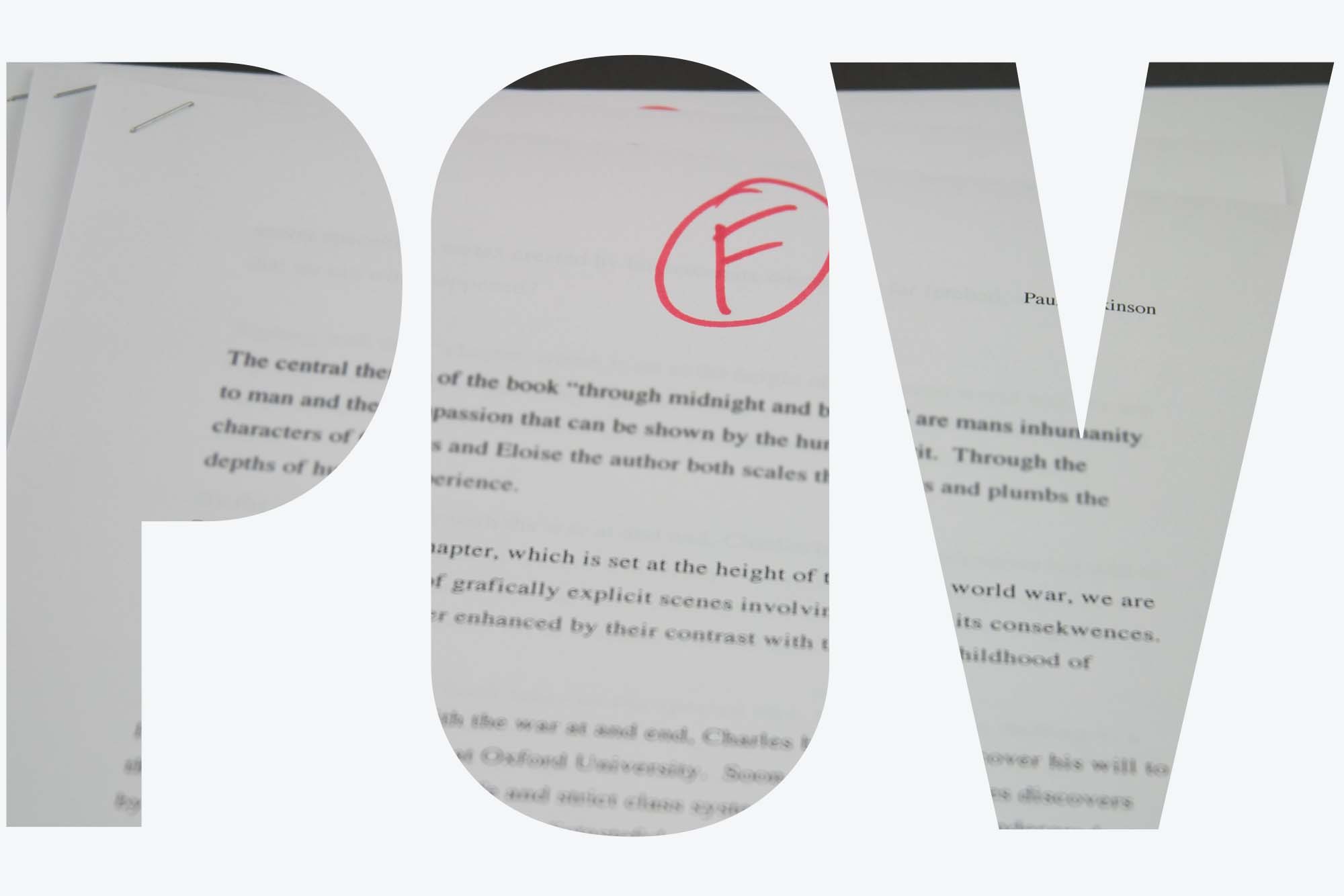

Why are university teachers, who pride themselves on critical thinking and ability to respond to research, still applying outdated assessment methods?

Since this is a week when grading and its discontents are on the minds of many instructors and students, here’s a pop quiz for you: how long has research shown us that grading is inconsistent and subjective?

A) 10+ years

B) 50+ years

C) 100+ years

If you answered C, you’d be right. A 1912 study found that 142 teachers graded the same English paper with results ranging from 50 percent to 98 percent. The percentage difference for geometry papers was even greater.

With evidence that has been verified many times over a century, why is it that university teachers, who pride themselves on their critical thinking and ability to respond to research, are still applying outdated methods of assessment?

Let’s address some common misconceptions.

Don’t students need feedback to improve? Yes! But grading isn’t the best way to provide it. When a conscientious instructor spends hours giving students careful feedback and gives them a grade, students frequently don’t look at the feedback. As Jeffrey Schinske and Kimberly Tanner—professors at Foothill College (Schinske) and Baylor University (Tanner)—explain, “Grading does not appear to provide effective feedback that constructively informs students’ future efforts.”

Doesn’t grading motivate students to learn more? No. Numerous studies confirm that grading dampens motivation to learn. Students become anxious about poor grades and more inclined to drop classes where their grades are lower. And even A students may not remember what they studied for a test—the performance is not about learning, but achieving the grade. In a study by Terence Crooks of the University of Otago in New Zealand, students themselves identified the desire for a good grade as being in conflict with the “fundamental goal of gaining a deep and enduring grasp of the subject.”

Doesn’t grading on a curve provide an accurate picture of learning in a class? No. Ryan S. Bowen and Melanie M. Cooper—Lipscomb University (Bowen) and Michigan State University (Cooper)—show that bell-curve grading relies on the construction of a “normal” student, without taking into account the differences that previous exposure to a subject and access to resources make to student performance. Plus, the focus on comparison rather than mastery diverts attention from student learning. Schinske and Tanner find that curve grading reinforces systemic inequities, contributing to “the loss of qualified, talented, and often underrepresented college students from science fields.”

Isn’t grading necessary for grad schools and employers to evaluate students? Not necessarily. Dozens of colleges and universities offer narrative evaluations rather than letter grades and attest that graduate schools and employers appreciate the multidimensional portraits such evaluations offer. Alexander Astin, author of Are You Smart Enough? How Colleges’ Obsession with Smartness Shortchanges Students, argues that as with professional performance reviews, narrative evaluations reveal key strengths and improvement over time. And surely it is telling that Harvard Medical School offers only pass/fail grades during preclerkship and principal clinical years to allow med students to “focus on becoming leaders in improving patient care rather than focusing on class rank.”

That’s a brief look at evidence against standard grading practices—there’s much, much more. And yet, a grade is required for every course at Boston University. Most faculty expend tremendous amounts of time and energy on grading, and most students spend copious amounts of time and energy worrying about grades. Students are frustrated, even angry, when they realize how little any future employer will care about their GPA. Understandably, students might ask why faculty continue grading them, in spite of the research showing that grades are biased, subjective, and inequitable, detrimental to real learning and student mental health.

Alternatives like contract grading, specifications grading, and dialogic grading—often collected under the term “ungrading”—require students to show what they’ve learned and hold them to high standards, but without some of the negative consequences of traditional grading. Many teachers switch to ungrading quietly and in solitude. However, as Muhammad Zaman, a College of Engineering professor of biomedical engineering, noted in a recent talk, “A single class changing grading is not going to solve the problem… We need to think about a broader cultural change.”

We have spent the past year strategizing about what that cultural change might look like, inspired by colleagues who have blazed the trail. Recently, the Kilachand Honors College adopted dialogic grading across most classes. Faculty in the CAS Writing Program held a faculty seminar on grading equitably; two of them wrote about successful experiments with the explicitly antiracist practice of labor-based grading. At a well-attended Lightning Talk sponsored by the Center for Teaching & Learning and Digital Learning & Innovation this spring, colleagues shared data on the harms of traditional grading and their own approaches to “Reimagining the Grading Paradigm.” Last month, another crowd turned out to hear Susan D. Blum, author of Ungrading: Why Rating Students Undermines Learning (and What to Do Instead) speak. We think BU is ready to reimagine grading publicly and collaboratively.

Boston University has committed to making students’ academic experience a top priority. This priority is compromised if we don’t acknowledge the compelling research that shows grading doesn’t help, and often hurts, meaningful learning. Grading is at odds with the “vibrant academic experiences” and “inclusive pedagogy that engages all students” that should be the hallmark of a BU education. We’re calling on the BU community to join us in applying critical thinking and academic rigor to the practice of grading.

Let’s be bold, BU. And let’s follow the research.

Carrie Preston is a College of Arts & Sciences professor of English and of women’s, gender, and sexuality studies and director of Kilachand Honors College; she can be reached at cjpresto@bu.edu.

Sarah Madsen Hardy is a CAS master lecturer and director of the CAS Writing Program; she can be reached at smhardy@bu.edu.

Davida Pines is a College of General Studies associate professor of rhetoric; she can be reached at dpines@bu.edu.

Deborah Breen is the director of BU’s Center for Teaching & Learning; she can be reached at dfbreen@bu.edu.

“POV” is an opinion page that provides timely commentaries from students, faculty, and staff on a variety of issues: on-campus, local, state, national, or international. Anyone interested in submitting a piece, which should be about 700 words long, should contact John O’Rourke at orourkej@bu.edu. BU Today reserves the right to reject or edit submissions. The views expressed are solely those of the author and are not intended to represent the views of Boston University.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.