Safe Driving on Mars

Alum steers rover on its search for signs of life

Matt Heverly doesn’t like to make a big deal of his job as the lead driver of the most expensive car in the solar system—NASA’s $2.5 billion, two-ton Curiosity rover, which is now roaming the surface of Mars.

“Basically, I’m a taxi driver,” says Heverly (ENG’05), a senior member of the technical staff in NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. “Scientists say, ‘Please take me over there,’ and then my job is to take them over there.”

Heverly and his team of 15 drivers take the scientists where they want to go by writing computer code, then sending it to Curiosity, which sometime in the next few hours does what it’s been been told. The desired destinations come from a host of international scientists involved with NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory Project, whose mission is to determine whether the Red Planet once harbored life’s basic elements: water, energy, and carbon.

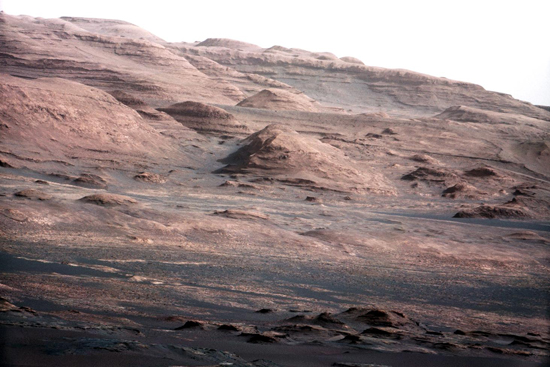

Curiosity has been on Mars for only four months, but the team has already made some impressive discoveries. After landing flawlessly in Gale Crater, the rover found rounded pebbles, indicating to geologists that the site had once been home to at least knee-deep water, clue number one that the planet could support life.

Then Monday, scientists associated with the project announced clue number two: organic compounds had been found in a sample of Martian soil. John Grotzinger, a project scientist with the Mars Science Laboratory, told scientists at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union about the find, but advised them that the origin of the compounds remained uncertain: they could have traveled with Curiosity from Earth or been deposited on Mars’ surface from its surrounding atmosphere, or they could be native.

“It will take time to work through this,” Grotzinger said. “Curiosity’s middle name is patience, and we all have to have a healthy dose of that.”

He said the team has had a series of “hootin’ ’n hollerin’” moments, occurring each time one of Curiosity’s 17 cameras and dozen-plus instruments—lasers, mini chemistry labs, and drills with names like alpha particle X-ray spectrometer, radiation assessment detector, dynamic albedo of neutrons—performs successfully.

Heverly and the drivers generally take the mission day by day, albeit Mars day by Mars day, translating a daily wish list from scientists of destinations and actions for the rover to take. They write and transfer computer code, and when the rover “wakes up” each Mars morning, it receives its to-do list, performs its tasks, and sends back pictures and data for scientists to crunch so the process can repeat the following day.

The routine seems perfectly normal, except the actions are carried out on another planet, one whose days are 40 minutes longer than Earth’s. The time differential made for an interesting first 90 days of the mission, when team members synched their lives to Mars time. At first it was easy—the workday started at 8:30 a.m., then 9:10 a.m., then 9:50 a.m.—but eventually days were turned completely upside down.

For Heverly, it meant that at 10 p.m., when he put his two young sons to bed, he would head off to a 12-hour workday. “My wife is a saint,” he says. “On weekends, she would take the kids out to the park for a while so that I could sleep. The kids didn’t understand Mars time, or why dad was at work all night, so they’d jump on the bed and say, ‘Dad, come play.’ I drank a lot of Red Bull or coffee.”

Spoken like a dedicated taxi driver.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.