news

Ruining the Spectacle: Nikita Gale’s END OF SUBJECT

by Darcy Olmstead

Nikita Gale’s 2022 installation, entitled END OF SUBJECT, at David Zwirner’s 52 Walker gallery is a wreck. It features a set of enormous bleachers, some bent and smashed, strewn haphazardly across the gallery (fig. 1). Visitors are invited to sit wherever they can, but any position on the cold metal is uncomfortable, making it impossible to observe the work with ease. What people then look upon is a confusing ruin: dangling cords, flashing spotlights pointing out at odd directions from the walls and the floor, and scratched metallic surfaces. It is as if one has entered a school gymnasium after it had been bombed.

In the aftermath of the explosion, a strange soundtrack bounces off the walls and flickering lights fill the room. Nikita Gale’s immersive installation includes an engineered soundscape: Toni Morrison reading Sula, an original audio track by composer Tashi Wada, beating rain, claps of thunder, laughing and crying, a dog barking, and the artist whistling.1 The soundtrack reverberates through a series of metallic prints on the walls of the gallery. Gale explains that “the sounds are from widely disparate contexts so there’s a sense of kind of sonically rummaging through ruins—tidbits and vignettes from widely varying environments and contexts.”2 Gale provides a stream of content in the soundtrack for the installation, but each sound is presented in fragments. Audience members are presented with a sonic archive full of holes and a gallery space in ruins. On the walls are Gale’s “Body Prints,” composed of burnished and painted aluminum panels incised with bodily words such as “finger,” “penis,” “mother,” etc. In an interview for the New York Times, Gale explained that she is “interested in using language to examine different systems that render a body legible as human, gendered, racialized, and so on.”3

In her installation practice, Gale is dismantling the spatial systems that anchor the observer to their own body, thus engaging with longstanding art historical inquiries into spectatorship. She presents a phenomenologically rich space, one that brings the ruins of an amphitheater or stadium into the gallery—all areas where power is negotiated and attention is controlled and directed. Amid bleachers and spotlights, the individual body of the viewer is dismantled into unrecognizable, uncategorizable parts.

Gale says that her initial proposal for the installation came from “thinking through how the activities and ‘tasks’ of the human sensory system… can activate or deactivate structures that inform how subjects… are rendered or alienated/made invisible.”4 Gale therefore acknowledges a long history of theoretical models discussing the observer. This history is famously explored in art historian Jonathan Crary’s 1992 Techniques of the Observer, in which the author examines how capitalism developed a visual model of consumption for the modern subject in the nineteenth century.5 Building upon the work of Michel Foucault, Crary produces a history of visuality that is based in modern systems of control:

[In the 1820s and 1830s] emerges a plurality of means to re-code the activity of the eye, to regiment it, to heighten its productivity and to prevent its distraction. Thus the imperatives of capitalist modernization, while demolishing the field of classical vision, generated techniques for imposing visual attentiveness, rationalizing sensation, and managing perception. They were disciplinary techniques.6

Crary discusses nineteenth-century optical devices—from the panorama, to the stereoscope, the camera, and eventually the moving picture—to examine how the human eye was “re-coded” for control.

Gale uses materials and structures within such a tradition critical of the materials and devices used to direct the modern observer. This is most evident in her discussion of the sporadic lighting installation for END OF SUBJECT, in which Gale positions spotlights on various metal prints and upon the columns of the gallery pointing in random directions:

I often use spotlights in my work because… they’re objects that tell you where to look and direct attention in a way that I find really seductive… So the spotlight is a useful metaphor for thinking about power in the context of the public arena: the stage, or wherever we focus our attention, represents where power is concentrated.7

The structures implemented for crowd control and dominant modes of visuality are concepts crucial throughout the installation. Gale takes sites of power like arenas and stages where observers are directed and restrained, and instead allows room for movement and distraction without purpose. The visitor is rarely comfortable, never allowed to be fully immersed in the work. Every auditory and visual disruption made throughout the performance is a means to break the spectacle.

The spectacle, as theorized by Guy Debord in Society of the Spectacle (1967), describes how the visual culture of modern society is used to regulate the spectator. Gale’s work rebuts the spectacle described by Debord: “the spectacle’s estrangement from the acting subject is expressed by the fact that the individual’s gestures are no longer his own; they are the gestures of someone else who represents them to him” on a screen or in an image.8 Gale seeks to counteract the spectacle through appeals to the individual’s corporeality. For one, visitors are forced to step over a series of wires and constantly move over and around sets of bleachers in END OF SUBJECT. Lights flicker on and off at random intervals, forcing viewers to use their sense of touch among other senses outside the visual. Debord, in one famous passage, writes that “when the real world is transformed into mere images, mere images become real beings—figments that provide the direct motivations for a hypnotic behavior.”9 Gale’s installation refuses to rely upon such methods. Any time a viewer begins to be immersed in one aspect of her work, the soundtrack or lighting pulls them from near hypnosis. The spectacle loses its hold.

Yet END TO SUBJECT does not merely seek to dismantle systems of power and visual control, but to bring the body back to the viewer through a form of what curator Eric Booker calls “reverse archaeology.”10 Gale’s implication of the spectator in her work comes from an anthropological understanding of architecture and technology informed by her degrees in archaeology and sociology. Describing her practice in the 2018 Studio Museum exhibition catalogue Fictions, Booker continues, “Initially drawn to an object for its aesthetic or physical qualities, the artist works her way back through each facet of its form—carefully researching its history and use, as well as evaluating the physical and personal experiences she has had with it.”11 She studies the way power is embedded in the gallery, the auditorium, or the arena, and then she disrupts it. Viewers thus step through the ruins of the spectacle itself.

Gale, rather than looking directly to a specific archive, investigates the archaeology of the present and proposes a space for the viewer to imagine bodily alternatives. In an interview with art21, Gale said that “It’s almost like I think of each of my works and each installation as a portal or an invitation to a conversation… [my installations] are creating a permanent record of a gestural, almost fugitive movement between structures or armatures associated with control.”12 Not only are her works future ruins, but future archives—she is attempting to force her spectators to act as archaeologists of their own lives. Debord wrote that “the real values of culture can be maintained only by actually negating culture. But this negation can no longer be a cultural negation. It may in a sense take place within culture, but points beyond it.”13 Gale’s spotlights never point directly upon objects in the room, but beyond them. In Gale’s work, the spectacle has been destroyed, but a space for conversation—a space to fabulate a new future where bodies cannot be so easily racialized, gendered, and coded for control—lies in the wreckage.

____________________

Darcy Olmstead is an MA candidate in Modern and Contemporary Art History (MODA) at Columbia University. Her current thesis seeks to explore artists’ publications in digital time by examining four recent projects by artists who utilize the form of the book to reflect on a world of chaos and hyper-culture brought about by digitization. She is originally from Fayetteville, Arkansas, and holds a BA from Washington and Lee University.

____________________

Footnotes

1. Madeline Schulz, “Nikita Gale ‘END OF SUBJECT’ at 52 Walker,” Flaunt Magazine, February 14, 2022, https://archive.flaunt.com/content/nikita-gale.

2. Nikita Gale quoted in Shulz, “Nikita Gale, ‘END OF SUBJECT’ at 52 Walker.”

3. Nikita Gale interviewed by Janelle Zara, “From Nikita Gale, A Panel Etched with ‘Blood,’ ‘Nerves’ and ‘Knee,’” New York Times, February 18, 2022.

4. Madeleine Seidel, “Nikita Gale: ‘END OF SUBJECT,’ 52 Walker, New York,” BURNAWAY, April 7, 2022, https://burnaway.org/magazine/gale-zwirner/.

5. Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer : On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992).

6. Crary, Techniques of the Observer, 24.

7. Janelle Zara, “From Nikita Gale, A Panel Etched with ‘Blood,’ ‘Nerves’ and ‘Knee,’” New York Times, February 2022.

8. Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle (1967), trans. Ken Knabb (London: Rebel Press, 2014), 10.

9. Debord, Society of the Spectacle, 5.

10. Eric Booker, “Object Complex,” in Fictions (New York: Studio Museum, 2018), 48.

11. Booker, “Object Complex,” 49.

12. Essence Harden, “In The Studio: Nikita Gale,” Art21, accessed March 21, 2022, https://art21.org/read/in-the-studio-nikita-gale/.

13. Debord, Society of the Spectacle, 114.

Reconsidering Performance Art: History, Tradition, and Contemporaneity at Chale Wote in Ga Mashie, Accra

by Colleen Foran

“That area looks ancient,” a cabdriver responded to my stated destination in Ga Mashie. While the neighborhood is not actually ancient, I understood the sentiment. Ga Mashie constitutes “Old Accra” and contains the Ghanaian capital’s oldest standing buildings.1 Constructed by European companies as defensive forts for trade goods, these structures date from the seventeenth century.2 The outposts later became hubs of the transatlantic slave trade (fig. 1).3 Prior to European incursion, the area was a village populated by fishermen from the Ga ethnic group. Many of the neighborhood’s current residents trace their lineage and livelihoods back to these inhabitants, even as the profession’s viability has declined due to climate change and industrial overfishing (fig. 2). Shipping and retail outposts that prospered during the colonial period have largely moved to the outer reaches of the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area.4 This economic decline has been paralleled by infrastructure decay.

Ga Mashie remains a vibrant and culturally rich space. The area echoes with the cheers and jeers of its famed boxing gyms, thumping base from funerals, and dice hitting plastic Ludo boards. Every year, residents perform vital processions like the Yams Festival for Twins and Hɔmɔwɔ Festival as markers of ethnic identity and social definition.5 Hɔmɔwɔ celebrates the end of a historical famine and is the most important event on the Ga community’s calendar.6 The Chale Wote Street Art Festival has become another annual marker for Ga Mashie. Held every August since 2011, the week-long event draws crowds from around Ghana and, increasingly, the world. The festival transfigures the space of Ga Mashie. Vendors and visitors throng John Evans Atta Mills High Street, closed to traffic for Saturday and Sunday (fig. 3).7 Artwork is installed in the historic forts (fig. 4) side-by-side with live performances activating the space (figs. 5, 6).8

Figure 3. Scene from 2022’s Chale Wote Street Art Festival with the Jamestown Lighthouse in the background. John Evans Atta Mills High Street, Accra, Ghana. Photograph by the author, 2022; Figure 4. Scene from 2022’s Chale Wote Street Art Festival with mural by Nii Nortey Hamid (b. Ghana, 1987) in the background. Ussher Fort, Accra, Ghana. Photograph by the author, 2022; Figure 5. Martin Toloku (b. Ghana, 1992). EnU va DZinYE (I’m Possessed) (2022). Durational performance. Chale Wote Street Art Festival, Ussher Fort, Accra, Ghana. Photograph by the author, 2022; Figure 6. Scene from Nana Yaw Ananse’s performance Pour Pure Power Proposal for African Prosperity and Posterity Proposal (2022) with clothing vendors in the background. Chale Wote Street Art Festival, Ussher Fort, Accra, Ghana. Photograph by the author, 2022.

Chale Wote also brings out many unofficial performers who dress as outlandishly as possible to draw attention and photography fees (fig. 7). Delighted attendees can join in the fun by paying to get their faces painted or by purchasing cheap plastic masks (see fig. 8). Coming across a procession, the spectator must guess if it is art, spectacle, or something in between. Through this productive confusion, Chale Wote challenges standard expectations for performance art.

I came across a poignant example of such blurred boundaries at the 2022 festival: a wheeled cart transformed by plywood into a helicopter was decorated with hand-painted slogans like “Fear God” and accompanied by children costumed in “Police F.B.I.” uniforms with fake semi-automatics (fig. 8). For an encouraged fee, onlookers could place their own children inside the helicopter for a photograph opportunity. I was left asking—was this a comment on American imperialism? A way to draw attention, and earn cedis, the Ghanaian currency, in the thronged High Street? Or was it just plain cool, a recreation of violent Hollywood films? I argue that the blurring of lines between critical art, commerce, and popular culture is an essential feature, not a bug, of Chale Wote, one that asks big questions around the purpose of short-term art events, the spaces in which they take place, and the audiences they exist to serve.

Because of the centrality of performance art to its program, Chale Wote has been correlated with the myriad contemporary art fairs and biennials that have cropped up since the turn of the twenty-first century. Biennalization both reflects and shapes what contemporaneity under globalization looks like and who it benefits; the audiences for such events are often Western European and American visitors who drop in for singular performances.9 And yet, even as it gains international renown, Chale Wote continues to draw a local audience. Organizers have sustained this interest by tying the festival into Ga Mashie’s long-standing ritual processions. Recent program materials have explicitly listed the Yams Festival for Twins and Hɔmɔwɔ as event kick-offs.10 These religious celebrations are presented as anchors for Chale Wote’s goal of bringing contemporary art into public space.11 This year, a Beninese group performed Egungun and Zangbeto masquerades in what promoters described as “the most versatile public performance[s] of mythical imagination in West Africa.”12

Seen within the context of Chale Wote, it becomes difficult to read the above as simply “traditional” examples of African masquerade.13 These processions are an integral part of the festival’s spectacle and its substance, entertaining while also serving a crucial function for community social and spatial self-fashioning within Ga Mashie. This calls into question what we consider contemporary and what we relegate to tradition. European and American art historians have typically discussed performance art as a break with tradition.14 African art history has theorized performance differently—signified, not least, by the fact that African art’s historiography often discusses “performance” without the appellation of “art.”15 Emerging out of the discipline of anthropology and the ethos of area studies, African performance is most often discussed as an expression of static ethnic identity.16

By placing cutting-edge artists in spatial conversation with historical ritual processions, Chale Wote underscores that performance art is nothing new in African art.17 Performance art is not always a radical break from “tradition” but can also be a continuation of a rich legacy of movement through space to address social issues and contest political realities. This conceptualization explains the festival’s staying power and the role it continues to play in the Ga Mashie community. Yet multiple interviewees have told me that the festival is at a tipping point. Many believe it is at risk of becoming purely a food fair—an excuse to drink beer, do some tchotchke shopping, and dance at evening concerts. As I write from the fall of 2022, Ghana is facing rampant inflation and extreme economic strife.18 My research works to understand whether a once-a-year event can do enough to change daily life for Ga Mashie residents. Will its performance art retain the political edge necessary to trouble the status quo? Or might Chale Wote’s critical, cutting-edge art be overwritten by its own spectacle?

____________________

Colleen Foran is a PhD candidate studying African art at Boston University. Her research focuses on contemporary West African art, particularly on public and participatory art in Ghana’s capital of Accra. Prior to coming to BU, Colleen worked at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art.

____________________

Footnotes

1. Abibata Shanni Mahama, Ama Twumwaa Acheampong, Oti Boateng Peprah, and Yaw Agyeman Boafo, Preliminary Report for Ga Mashie Urban Design Lab (New York: Millennium Cities Initiative, 2011), 2.

2. D. A. Tetteh and K. Y. Tuafo, James Town, British Accra: A Brief History, Luminaries & Landmarks (Accra, Ghana: African Stories Press, 2018), 9–11, 17.

3. While the forts were originally built to house material goods, the rapid growth of the slave trade meant that the buildings were repurposed to cruelly house human beings kidnapped from their communities to be transported and sold in South and North America and the Caribbean. Today, the only forts still standing in Ga Mashie are James Fort and Ussher Fort, though others are extant throughout Accra and Ghana. While these forts have been declared UNESCO World Heritage sites, their levels of preservation vary. They are often in very bad condition; UNESCO World Heritage Convention, “Forts and Castles, Volta, Greater Accra, Central and Western Regions,” accessed November 10, 2022, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/34/.

4. The colonial era in Ghana ended in 1957, when it declared its independence from the United Kingdom. However, Ga Mashie’s economic decline is considered to have begun earlier. Many peg this to the 1920s, citing the 1921 construction of new market halls at Central, or Makola, Market and the 1928 opening of a deep-water port at Takoradi (as opposed to Ga Mashie’s “surf port,” which was more challenging to navigate for large vessels). Nonetheless, even if many wholesalers had left Ga Mashie by independence, the upscale department stores for which the area was known largely remained operational until moving to the suburbs in the 1950s and ’60s; Iain Jackson, Sharing Stories from Jamestown: The Creation of Mercantile Accra (Liverpool, UK: Liverpool School of Architecture, 2019), 68, 91, 93; Nate Plageman, “Colonial Ambition, Common Sense Thinking, and the Making of Takoradi Harbor, Gold Coast,” History in Africa 40 (2013): 332–33.

5. For more on how processional acts serve as both spatial and political acts of boundary-marking for the Ga people, see John Kwadwo Osei-Tutu, “‘Space’, and the Marking of ‘Space’ in Ga History, Culture, and Politics,” Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana 4/5 (2000–01): 55–81.

6. For more detail on how these events are performed and their duration, see Mariam Goshadze, “When the Deities Visit for Hɔmɔwɔ: Translating Religion in the Language of the Secular,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 87, no. 1 (March 2019): 191–224, and Marion Kilson, Dancing with the Gods: Essays in Ga Ritual (Lanham, MA: University Press of America, 2013).

7. While the festival lasts for about a week, the action is concentrated on the concluding Saturday and Sunday. The workweek includes panels, talks, and screenings in the lead up, but many of these take place away from Ga Mashie in other parts of Accra.

8. Some of these are durational feats of artistic endurance, while others are fleeting (respectively, see figs. 5, 6). The latter makes it easy for the visitor to miss some of the performances.

9. For more on how the growth of biennials can be understood to reflect the conditions of globalization, as well as an optimistic read on their potential to engender resistance to the hegemonic world order, see Caroline Jones, The Global Work of Art: World’s Fairs, Biennials, and the Aesthetics of Experience (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

10. Uplifting Ga culture has been a part of the festival’s fabric from its beginning: An undated proposal and budget given to me by Gabriel Nii Teiko Tagoe, the executive director of the Ga Mashie Development Agency (GAMADA) department within the Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA), introduces “The Kpanlogo Musical Fiesta.” It suggests a festival to draw tourists to Ga Mashie for concerts of the Ga music and dance known as Kpanlogo. According to the document, this will revitalize the fading genre as a means of “bring[ing] back the social cohesion that these communities enjoyed when this music and dance form was alive.” Tagoe told me this proposal was the seed for what would become Chale Wote, although the actual origins of the event are somewhat obscure and many claim credit for its ideation; Gabriel Nii Teiko Tagoe (executive director, GAMADA), in discussion with the author, September 7, 2022, GAMADA offices, Accra, Ghana.

11. The festival has also crafted new rituals, including the Day of ReMembering, a yearly procession held since 2017 where performers move through the space of Ga Mashie to honor those ancestors forcibly marched to the slave forts along the same streets; Kwame Boafo (performance artist and 2022 organizer, Chale Wote), in discussion with the author, November 10, 2022, Zoom.

12. Chale Wote organizers often present the festival as a pan-Africanist endeavor in their online and printed materials, reinforcing the idea that their interest in and respect for historical African performance is not limited to Ghanaian processions; Chale Wote Street Art Festival, “An exploration of a visual language, for the most versatile public performance of mythical imagination in West Africa; EGUNGUN+ ZANGBETOR,” August 28, 2022, https://www.facebook.com/Chalewotefest/posts/

pfbid0izRgznjPZvm35U3TPKYfDFmCGYc3MNcTPiSuzv41yzMiaYPzTHj2sQEA8BVspWtMl.

13. In African art historiography, “masquerade” is a more encompassing term that describes not only events where participants are wearing a mask or disguising their appearance. It can also include all events that feature a performer moving through space as a means of collective cultural definition.

14. The standard Western teleological account of the development of modern and contemporary art presumes a rupture model, with innovation followed by stagnation followed by repudiation that leads to innovation. Typically, the origins of performance art are located with European Dada artists working in the interwar period. The Dadaists’ ideas came to full fruition with American Fluxus artists and theorists and with the Viennese Actionists in the 1960s as they tore down the remaining boundaries between art and life. It is important to note that this “rupture” model has come under increasing scrutiny in recent years and has long been critiqued for framing these artistic movements as a mode of radical “avant-garde” politics.

15. See, for example, Frances Harding, ed., The Performance Arts in Africa: A Reader (London: Routledge, 2002) and Ruth M. Stone, “Performance in Contemporary African Arts: A Prologue,” Journal of Folklore Research 25, no. 1/2 (1988): 3–15.

16. Beyond the limitations placed on our understanding of African performance art, this framework also ignores the over-a-century-long interaction between classical African and modern art from Europe and the United States, as well as the robust interchange between continents that occurred for centuries outside the colonial history within which “contact” is commonly couched.

17. As scholars Salah Hassan and Olu Oguibe have argued, “if any creative or critical strategy establishes a firm link between contemporary and classical African art, that strategy is conceptualism,” Salah Hassan and Olu Oguibe, “Authentic/Ex-centric: Conceptualism in Contemporary African Art,” Authentic/Ex-centric: Conceptualism in Contemporary African Art (Ithaca, NY: Forum for African Arts, 2001), 10–23.

18. Over the past year, the Ghanaian cedi’s value against the American dollar has depreciated by almost fifty percent and many have begun to call for the current president Nana Akufo-Addo to resign; Thomas Naadi, “Ghana Undergoing Worst Economic Crisis - President,” BBC News, October 31, 2022, accessed November 7, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/ news/world/africa?ns_mchannel=social&ns_source

=twitter&ns_campaign=bbc_live&ns_linkname=635f49cb49d9ef23494b8a44%26

Ghana%20undergoing%20worst%20economic%20crisis%20-%20president%262022-10-31T04%3A31%3A16.035Z&ns_fee=0&pinned_post_locator=

urn:asset:e0f7eb3c-4252-4c86-b119-a6b28691b3d1&pinned_post_asset_

id=635f49cb49d9ef23494b8a44&pinned_post_type=share.

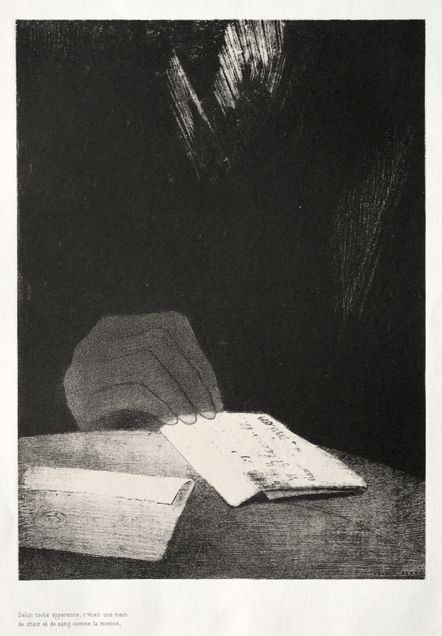

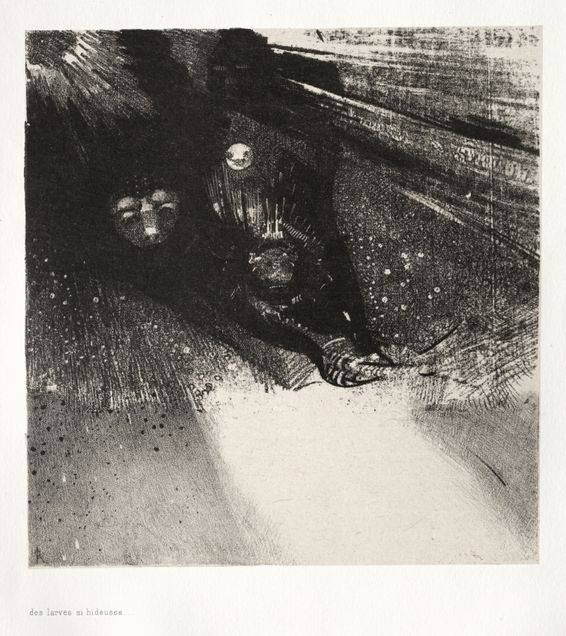

From Léon Spilliaert’s Vertigo to…?

by Jin Wang

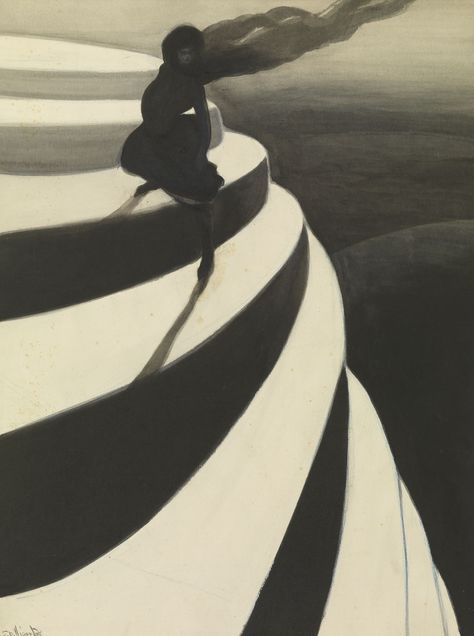

A few years ago, I stepped onto a train in Brussels and accidentally ended up in Ostend, where I first encountered works by the Belgian painter and graphic artist Léon Spilliaert. Wandering in the city’s museum, the Mu.ZEE, I was immediately intrigued by Spilliaert’s Vertigo (fig. 1, 1908). Similarly enthralled, a group of school kids surrounded the painting—studying the work by drawing (fig. 2).

In Vertigo, a female figure sitting on spiral stairs by the sea dominates the composition. The exaggerated perspective of the stairs abstracted into simple geometric shapes implies a sense of hypnotic danger. There is a sense of imbalance in the woman as she uncomfortably sits with one leg crossed on the step while a strong wind lifts her scarf and hair high up into the sky. It seems that she could fall down the stairs or be carried away by the wind at any moment. But facing danger, she resists all these external forces of vertigo that aim to push her into the abyss.

Spilliaert no doubt experimented with the fear of falling or manifesting the dangers of an enigmatic force from the surrounding void that threatens to take the human figure away. An early draft of Vertigo further explores this sense of danger. In the previous version, the perspective of the stairs is ever more extreme and the woman, shown frontal with her leg crossed, loses her balance and is at the point of falling. The finished work, however, is modified to depict the resistance from the woman: by showing her sitting with legs crossed from the side instead of the front, the posture of sitting is emphasized to anchor the figure to the stairs. Thus, by balancing the figure’s body to compensate for the dangerous environment, Spilliaert was not only interested in the experience of vertigo, but the refusal of the human figure to lapse into the complete unconscious.

The tension between spatial dynamism and the simultaneous resistance/trance of the human figures to the environment is an omnipresent theme in Spilliaert’s early works on paper from 1900 to 1910. These works depict imminent death, femme fatale, and mysticism—themes that very much align with the Symbolist movement.1 Precisely, the existing literature frames Spilliaert as a transitional figure from Belgian Symbolism to Flemish Expressionism.2 Also, this narrative toward symbolism is accompanied by an identity of a Nietzchean genius loner he constructed. Due to chronic stomach aches, he suffered insomnia and became known for wandering around the city at night. However, this can be contested by the fact that his work is always about his hometown Ostend—something that is often ignored beyond a biographical account. Even sometimes only an abstract backdrop, the iconic seascape and cityscape of the city provides enough specificity to distinguish his work from Symbolism. While Spilliaert’s paintings are based on his experience of his surroundings, the Symbolist generalized the locations to eternalize “essences” by constructing universal, idealized imagery.

Spilliaert’s images relate to a new aesthetic theory based on psychology and to spatial concerns amid rapid socio-economic changes. The cityscape and seascape are usually abstracted, or sometimes even void, which stands in contrast with human figures who resist a certain degree of abstraction. Here, I use abstraction as the opposite of figuration—just as the woman in Vertigo who is deliberately anchored onto the geometric stairs and exists within the barren seascape. In this way, abstraction is equivalent to the ominous lure of the surrounding environment which evokes the turn-of-the-century discourse of empathy theories (Einfühlung).3

Spilliaert’s work especially embodies Wilhelm Worringer’s conception of two binary urges, namely abstraction and empathy.4 Though there is no evidence of direct connection between the two, the overlaps between Spilliaert’s works and Worringer’s theories prove the shared sentiment in contemporary Europe where Einfühlung intervened in the construction of a new aesthetic. By animating the surrounding objects while destabilizing the subjects of viewership through psychological empathy, Einfühlung extends optical visions to haptic and bodily experience.

The binary impulses of Ostend, as experienced by Spilliaert, were the reality for the locals: an exciting city in summer and a morbid town in winter, or a joyful resort in the daytime and a deserted provincial town at night. The lure of the surrounding environment has been discussed in the context of rapid industrialization in turn-of-the-century Europe, where dwellers were simultaneously mesmerized and alienated by the city. Ostend was the fastest modernized city besides Brussels in the new nation of Belgium, favored by the King and funded by colonial expansion in Congo. This city quickly transformed from a small fishing village to an international summer resort with royal establishments.5 The new infrastructure is recorded in Spilliaert’s works: the Kursaal, the Villa Royale, the Galerie Royales, the Royal Theaters, and the Church of Saint Peter and Paul. Therefore, an empathetic reading of Spilliaert’s oeuvre helps to connect fragmented visual elements, especially between the metaphysical manifestation of binary urges and the specific reference to Ostend’s locality.

Today, along the promenade by the sea through the Galeries Royales, stands the sculpture by Herlinde Seynaeve, Umbra , created to pay homage to Spilliaert’s Vertigo (fig. 3, 2002). While Spilliaert was intrigued by the darkness of his hometown wandering at night in self-estrangement, maybe it is time to reconsider “darkness” as part of the historical development of the city. His work is a product of when the city’s new and exciting infrastructure was built through colonialism and imperialism in the late nineteenth century. To address the homage to Spilliaert, we should build upon the reflections of historian Debora Silverman when studying Art Nouveau; especially how the atrocities happening in Congo could materially and aesthetically influence artistic and stylistic endeavors at the turn-of-the-century Belgium.6 In this sense, I wonder, what kind of homage is relevant to pay to this understudied artist in Belgian modern art history? The question haunts me as I write, and I am still working on it.

In this research project about Spilliaert, I will construct a narrative beyond the biographical reading of his work which prevails in the existing scholarship that conveniently situates him in the Belgian Symbolist movement. Instead, I focus on the uncanny approach to his immediate surroundings. In his cityscape and seascape that evoke fears of immediate danger, of falling, of abstraction, and of agoraphobia, these themes are sharply different from, for example, James Ensor’s imagination of the same space when depicting carnivals and beach parties happening in daylight.7 Therefore, I propose to empathetically look at Spilliaert’s works and especially the binary impulses underlying the depiction of Ostend. By insisting on the artist’s response to the rapid transformation of his city from the small fishing village to a modern and seasonally touristic provincial town, I want to contextualize Spilliaert’s paintings as part of the newly established Imperial Belgium and how his work responds to the colonial exploitation of Congo.

____________________

Jin Wang is a doctoral student in art history at the Graduate Center, CUNY. She focuses on modern and contemporary art in a global context and is interested in transcultural and intercultural exchanges, modernisms, and decolonial/postcolonial practices.

____________________

Footnotes

1. For more on Spilliaert’s works see Anne Adriaens-Pannier, Léon Spilliaert: From the Depths of the Soul (Brussels: Ludion Publishers, 2019), Adriaens-Pannier, Noémie Goldman, Adrian Locke, et al., Léon Spilliaert (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2020), Adriaens-Pannier and Leïla Jarbouai, Léon Spilliaert, 1881-1946: lumière et solitude (Paris: Réunion des musées naitionaux, 2020), Francine-Claire Legrand, Patricia Adams Farmer, Frank Edebau, et al., Léon Spilliaert: Symbol and Expression in 20th Century Belgian Art (Washington DC: The Phillips Collection, 1980), and Xavier Tricot, Léon Spilliaert: Catalogue Raisonne of the Prints (Antwerp: Pandora Publishers, 2020).

2. Ralph Gleis, Decadence and Dark Dreams: Belgian Symbolism (Munich: Hirmer Verlag, 2020). Stephen Goddard and Jane Block, Les XX and the Belgian Avant-Garde: Prints, Drawings, and Books, ca. 1890 (Lawrence, KS: Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, 1992). Jeffery W. Howe, Nature’s Mirror: Reality and Symbol in Belgian Landscape (Chestnut Hill, MA: McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, 2017).

3. The concept of Einfühlung, developed in late nineteenth-century Germany, generally describes the projection of subjective feeling onto the objective world. The discourse overlaps with diverse contemporary fields such as philosophy, aesthetics, psychology, optics, art history, architecture, among others. It often refers to embodied responses generated by encountering specific things such as an image, object, or spatial environment. Juliet Koss, “On the Limits of Empathy,” The Art Bulletin 8, no.1 (March 2006): 139–157.

4. In his 1908 book Abstraction and Empathy, Worringer identifies two opposing forces in the history of art: abstraction and empathy (or mimesis). He claimed that abstraction (simplified and flat images) could be observed in societies where people had relatively hostile relationships with the outside world. Worringer argues that the attention to detail seen in more naturalistic styles, on the other hand, is the product of either classical or modern societies in which people lived harmoniously in the environment. Wilhelm Worringer, Abstraction and Empathy: A Contribution to the Psychology of Style, trans. Michael Bullock (New York: International Universities Press, 1953).

5. Marcel Vanhamme and Jean Delporte. Ostende: d’un village de pecheurs à la reine des plages (Brussels: CLAP, 1982).

6. Debora L. Silverman, “Art Nouveau, Art of Darkness: African Lineages of Belgian Modernism Part I.” West 86th 18, no. 2 (Fall-Winter 2011): 139-181; “…Part II,” West 86th 19, no. 2 (Fall-Winter 2012): 175-195; “…Part III,” West 86th 20, no. 1 (Spring-Summer 2013): 3–61.

7. Inne Gheeraert and Mieke Mels, Ensor and Spilliaert: Two Great Ostend Masters (Ostend: Kustmuseum ann zee, 2016).

(Under)Water: The Mary L. Cornille (GRS’87) 38th Annual Boston University Graduate Symposium in the History of Art & Architecture

April 2, 2022

Boston University

by Katherine Mitchell and Francesca Soriano, Co-organizers

(Under)Water, this year’s Mary L. Cornille (GRS’87) 38th Annual Boston University Graduate Symposium in the History of Art & Architecture, took place on April 2, 2022. Eight graduate student panelists and keynote speaker Dr. Stacy L. Kamehiro (Associate Professor in the History of Art and Visual Culture Department, University of California Santa Cruz) considered and responded to the role of water in shaping the production of visual and material culture. Sponsor Mary L. Cornille, who attended this year’s event, remarked upon the creativity of the presentations and the diversity of approaches to a theme that may sound unrelated to art historical scholarship.

Water has long occupied a place in art and image-making as subject, inspiration, and material. The universality of water serves as a useful framework for uniting visual and material production across cultures, geographies, and centuries. Its innumerable and perpetually changing forms can also highlight differences. Bodies of water provide food, materials, commodities, and waste disposal for human communities. They also function as spaces of transit, connection, exploration, and trade, and as sites of religious observance and social identity. Water and water bodies are a source of mystery, myth, and danger. The challenges posed to humans by both too much and too little water continue today. Expanding scholarship in the green and blue humanities considers the important presence of the natural force of water and its environs in cultural and visual production.

The papers in the morning panel took up the theme of “Water as Resource.” Moderated by PhD student Hannah Jew and with technical support from PhD student Colleen Foran, the panelists discussed themes of danger and control. Krista Mileva-Frank (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) opened the day by sharing her research on aquariums. In “Troglodytic Technology: The Grotto Aquaria of the Expositions Universelles,” she discussed immersive viewership and themes of control and spectacle in exhibits that mimic underwater submersion. Marina Wells (Boston University) highlighted gender construction and conceptions of water-related danger in images related to the nineteenth-century whaling industry in “Selling Maritime Men: The First American Whaling Images and the Masculinity they Produced.” The third paper in this panel, presented by Dada Wang (University of California, Davis), moved from historical to contemporary work. In her talk “Reframing Narratives of Water Control: Mechanisms of Resistance in Chinese Performance Art,” she shared fascinating examples of water-based performance art and how they confronted and engaged with governmental water policies in China. Finally, Murtaza Shakir (Columbia University) considered public wells—their construction and placement—within the context of the Islamic institutionalization of providing drinking water to all citizens during in the Fatimid era in his paper, “The Fatimid-era Well in al-Jāmiʿ al-Anwar: An Inspiration for a Retrospective Study of the Islamic Tradition of Siqāyah.”

The group reconvened after a lunch break for a keynote lecture by Dr. Stacy L. Kamehiro, Associate Professor in the History of Art and Visual Culture Department at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Dr. Kamehiro’s lecture included a discussion of her thought process and art historical approaches as she wove together themes from the student papers. She bridged the two panels in three sections: “(Under)Water,” “Water as Worlding,” and “Vā Moana: Water as Place and Path.” Dr. Kamehiro considered themes such as water as a life force rather than death force in Oceania and Oceanic culture; water as related to movement and transformation in contemporary works; and the need for storytelling in considerations of and activist work to fight climate change, respectively. She included a detailed discussion of her ongoing research on the world tour of Hawaiian King Kalākaua and water as a pathway for Hawaiian survival, transportation, resources, and exchange. Dr. Kamehiro concluded with a consideration of water as linking space and time and its centrality to Oceanic art and visual culture. Following her lecture, PhD student Renée Brown moderated an engaging and thought-provoking discussion.

The second student panel of the day, “Water as Connector,” was moderated by PhD student Carter Jackson with technical support from PhD candidate Alex Yen. The four papers continued threads and themes from the morning panel and keynote, and highlighted the myriad ways that water can, and has, permeated the creation of visual and material culture. Alexandra Creola (University of Michigan) began the afternoon panel by examining nymph cults in southern Italy and considered why Greek colonists depicted nymphs in specific and unique ways. Her paper, “Embodiments of Sacred Waters: Artistic Depictions of Water Nymphs in the Ancient Greek Colonies of Southern Italy,” discussed water as a liminal space through careful examination of figural representations. In the next presentation, “Floating Forests: The Pacific Ocean in Oh Haji’s Textiles,” Soo-Min Shim (Australian National University) presented water as a site that connects movement. She provided an in-depth analysis of Zainichi Korean artist Oh Haji’s textiles in terms of their installation and materiality and considered how they use a decolonial framework to destabilize the viewer and fight visual boundaries of land and ocean. Gabriella Johnson (University of Delaware), in her talk “The Triumph of Trapani Coral,” considered water as a site of material extraction and identified sea coral as a distinctly Sicilian material that circulated globally. She addressed the unsustainability of coral harvesting practices and used methods of eco-materialism to conclude that coral was symbolic of the Habsburgian Spanish empire. In “Liquescent Interiors: Water in French Decorative Wallpaper, 1804–1863,” Ivana Dizdar (University of Toronto) introduced the concept of hydroimperialism and discussed the crucial role of water, and the places where land and water meet, in colonial interaction. She also highlighted various water bodies, including rivers and arctic waterscapes, in her reading of nineteenth-century French decorative wallpaper.

Nine thoughtful and thought-provoking talks, as well as active participation in the discussion from the History of Art & Architecture community, made for an engaging day. We were delighted to see that connections between the papers and themes sparked interesting discussions. This event would not have been possible without the student volunteers who helped edit the Call for Papers, read and reviewed numerous abstracts, advanced slides for the presenters, and moderated questions. Further support from Susan Rice, Cheryl Crombie, Gabrielle Cole, and Professors Michael Zell and Becky Martin was invaluable. Despite the challenges of the Zoom format, presenters joined from four different continents, bringing together an array of perspectives and ideas. We hope that these productive conversations were just the beginning of collaborations and further considerations of water in relation to visual and material culture.

____________________

Katherine Mitchell is a PhD candidate in history of art and architecture at Boston University. Her ongoing dissertation research is focused on the history of riverine photography in the nineteenth-century United States as an instrument of imperial control and illustration of Euro-American ecological sensibilities.

Francesca Soriano is a PhD candidate in history of art and architecture at Boston University. Her dissertation research is focused on U.S. art and visual culture associated with South American and Caribbean birds and avian products in the nineteenth century and how it participated in imperialistic activities as well as a hemispheric extractive economy.

Tomás Saraceno: Particular Matter(s)

The Shed, New York, NY

February 11–April 17, 2022

by Sarah-Rose Hansen

Over the course of the eight galleries in Tomás Saraceno’s Particular Matter(s) exhibition, which was on view through mid-April at The Shed in midtown Manhattan, three separate moments introduce lighting shifts that are likely to cause the viewer to pause for pupillary adaptation. In day-to-day life, moments of ocular adjustment are, at best, an incidental inconvenience. In Particular Matter(s), however, dramatic light environments constitute, for Saraceno and Shed curator Emma Enderby, the exhibition’s luminous lifeblood. By harnessing the narrative power of night and day, the Argentine-born, Berlin-based artist’s lightscapes compel viewers to consider both the beauty and the gravity of the exhibition’s “call for environmental justice.”1

Saraceno's photic narrative begins with the near pitch-blackness of Webs of At-tent(s)-ion (2020), in the first gallery (fig. 1). The shift from the vivid springtime daylight of the exhibition entryway to this gallery’s fully darkened interior is accompanied by the first of the installation’s moments of visual adjustment. After stepping through a weighty blackout curtain, viewers must pause to allow for a moment of “dark adaptation,” a scientific term used to refer to the physiological process of pupil dilation and rod activation that allows the human eye to see at night.2 After this disarming moment, visitors begin to move through the gallery to marvel at seven stunningly intricate, spot-lit spiderwebs, which are dusted with noctilucent fibers and encased in glass displays.3 Through this process, the darkened viewing space takes on an atmosphere of peace and contemplation, allowing the viewer to meditate on issues that Saraceno points to in his co-authored wall texts, such as “the rights of invertebrates” who “feel the harmful, environmental effects of the Capitalocene.”4

A second dramatic light shift meets viewers in the second gallery, where the exhibition’s namesake work, Particular Matter(s) (2020), is visually composed of a light beam plus the “cosmic dust” and PM2.5 it illuminates.5 Upon entry, spectators are briefly, ocularly overwhelmed by the forceful light beam, which is aimed at the room’s doorway. Viewers are forced to undergo a rapid “light adaptation”—the reverse physiological process from dark adaptation—and upon moving out of the spotlight, a renewed adjustment to the darkness, which fills the room beyond its luminous entry point (fig. 2). Once inside this tranquil, darkened viewing area, beholders can stand back and observe the light or approach it from the side and manipulate it. Saraceno suggests, in his wall text, that visitors also consider the pollution on which the gallery’s particle illumination centers its focus. This beholding area reiterates the concept of darkness introduced in Webs of At-tent(s)-ion, suggesting that it is a space for reflecting on serious issues that might at first cause discomfort, but that can ultimately stimulate peaceful contemplation and discovery. This darkness, which in some artistic contexts can function independently of an idea of night, becomes firmly nocturnally linked in the next room through iconographic references to the moon, in pollution-inequality-referencing Shed commission We Do Not All Breathe the Same Air (2019–2022), and the occult, in Arachnomancy Cards (2018–2022).6

After two more rooms of experiencing the nocturnal, with sonic work Sounding the Air (2020) and the red-laser-illuminated spider silk webs of How to entangle the universe in a spider/web? (2020), viewers make their way into the soft-gray lighting of A Thermodynamic Imaginary (2020). Amidst a skyscape of suspended mylar orbs, which suggests the ecological interconnectedness of the entire universe, an inflection point emerges in Saraceno’s photic trajectory (fig. 3). A large projected film portrays the exact moment of a solar eclipse, with a powerful ray of sunlight just beginning to emerge as the video cuts and is looped again.

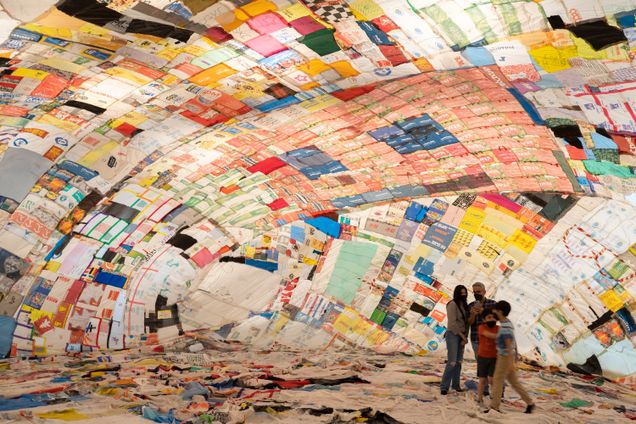

From this point onwards, the emergence of light becomes a focus of Saraceno’s narrative. In Free the Air: How to hear the universe in a spider/web (2022), an immersive installation specially commissioned by The Shed for Particular Matter(s), viewers lie down on one of two ninety-five-feet-diameter webs, which are horizontally suspended one above the other, at forty feet and twelve feet from the ground, respectively (fig. 4). At the end of a darkened, eight-minute symphony, which includes atmospheric and rumbling sounds with accompanying vibrations felt through the suspended webs, a sunlike luminescent orb at the top of the ovoid room brightens to full radiance. Visual adaptation again becomes central; as viewers begin to sit up from the symphony, they must allow their eyes to adjust and take in the luminosity of day.

The final work of the exhibition, which follows the visitor’s exit from Free the Air, gives artistic form to Saraceno’s environmentalist vision.7 Museo Aero Solar (2007), a solar balloon made of crowd-sourced plastic bags—a specific repurposing of the PM2.5 pollutants referenced earlier in the show—is presented in vibrant color (fig. 5). The brightly lit room feels powerfully diurnal and vividly optimistic. With this concluding installation, Saraceno has embraced the full nychthemeron; he has encouraged viewers’ discovery of night’s mysteries and then, in stages, of a daylight call to action. In this incorporation of both nocturnality and diurnality, Saraceno joins a long tradition of scholars and artists who have worked outside a Manichaean characterization of the night as evil, instead understanding the after-dark as multifaceted, with dynamic contemplative potential.8

The effect of this dual embrace is powerfully poignant; Saraceno’s viewers walk away from the exhibition equipped not only with an impulse towards the expansive optimism of daylight, but also, crucially, with a nocturnal pathway to reach that disposition. Saraceno’s vision—sustainable, egalitarian, interconnected—is ambitious, but through Particular Matter(s)’s illuminative journey from night into day, he inspires us to believe it is possible.

____________________

Sarah-Rose Hansen is an MA candidate in art history at Columbia University. Her current research deals with representations of the nocturnal in the sixteenth-century Veneto. She holds a Graduate Diploma in the history of art from the University of Warwick and a BA in psychology and Portuguese from Stanford University.

____________________

Footnotes

1. Wall text, Particular Matter(s), The Shed, New York.

2. This review makes reference to physiological processes that are specific to beholders who can see; it does not seek to represent the experiences of visitors who are blind or who have low vision.

3. The spotlights are directly listed among the work’s materials on Webs of At-tent(s)-ion’s wall panel.

4. Wall text, Particular Matter(s), The Shed, New York. There is an extensive literature on the Capitalocene outside the context of Saraceno’s work. It is defined in the exhibition’s introductory wall text as “the current era of Earth’s existence characterized by the destructive effects of capitalism on the environment.”

5. Wall text, Particular Matter(s), The Shed, New York. The “cosmic dust” and “PM2.5” descriptors pertain to the room’s naturally occurring dust particles, which are made visible by the powerful light beam. “Cosmic dust” refers to the non-earthly origins of some dust particles, while PM2.5 refers to a specific pollutant, one of the most harmful.

6. Practices of the occult have a long-established tradition of taking place at night.

7. The Shed’s website, and a gallery attendant on the day of this author’s visit, make it clear that the order of artworks described in this review is the order recommended by the artist. In a logistical rearrangement on the part of the venue, however, many viewers are guided to Free the Air prior to visiting the initial six rooms of galleries. The final installation room, in either trajectory, is Museo Aero Solar, but its positioning up an escalator makes it possible to miss. Saraceno’s works are easily compelling enough to stand outside of his exact intended ordering, but the subtle power of the luminous buildup is partially inverted in the rearranged viewing.

8. See, for two examples of more complex considerations of night, Pseudo-Dionysius and Saint John of the Cross.

White Shadows: Anneliese Hager and the Camera-less Photograph

Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA

March 4–July 31, 2022

by Renée Brown

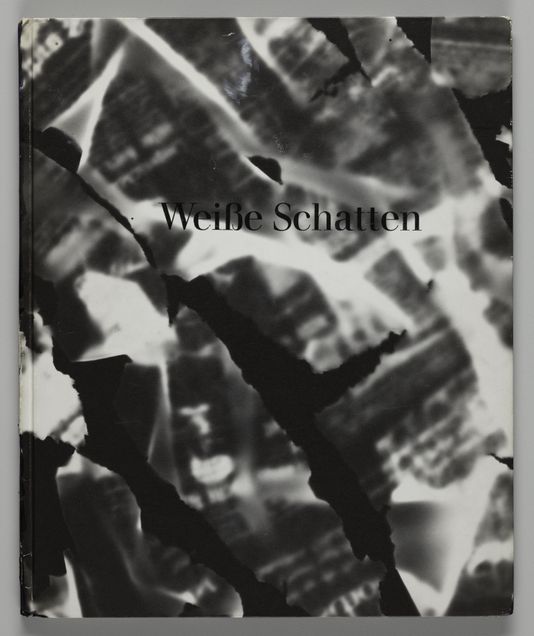

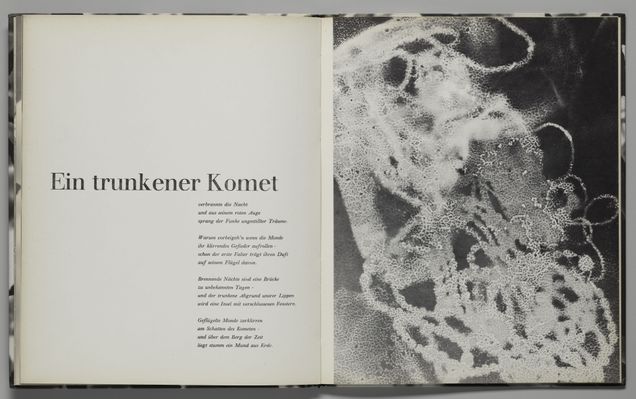

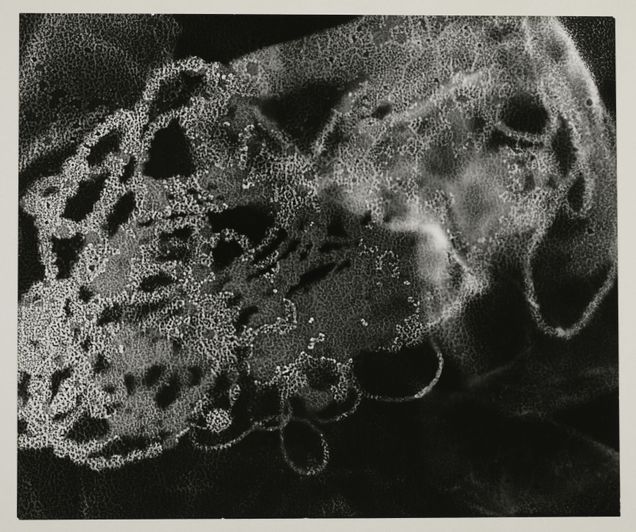

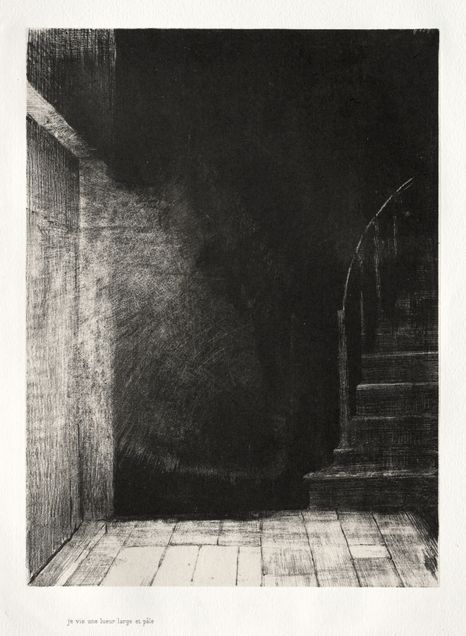

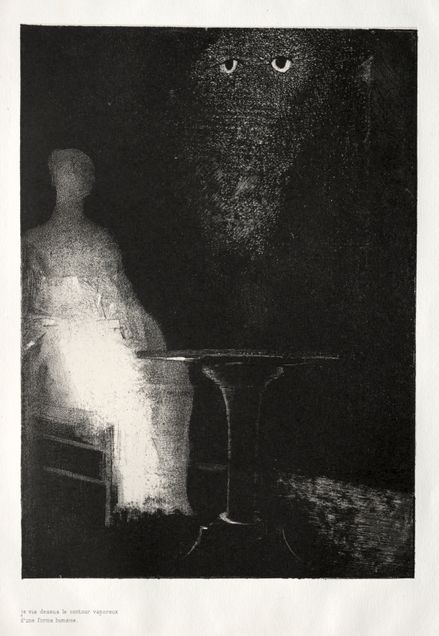

In 1964 German artist Anneliese Hager (1904–1997) published a book of her poems and photograms entitled Weiße Schatten (White Shadows). Released in an edition of fifty-five, each volume has a unique cover featuring a full-bleed photogram by Hager (fig. 1). The layered black and white images both invite and frustrate the urge to decipher; blurred lines of typed and handwritten text hover at the limits of legibility while geometric patterns suggest textile and organic forms but refuse categorization as one or the other. The book’s contents are no less enigmatic. Reproductions of abstract photograms suggesting vapor, cosmic dust, riverbeds, rumpled bed sheets, and skin cells juxtapose German poems bearing titles like “Zwischen Zeit und Stunde” (Between Time and Hour), “Halluzination” (Hallucination), “Nebel” (Fog), “Ein Trunkener Komet” (A Drunken Comet), and “Sirenengesang” (Siren Song). Text and image neither explicate nor illustrate each other but engage in an oblique dialogue. For instance, the photogram accompanying “A Drunken Comet” shows a tangle of beaded lines evoking the erratic trajectory of the poem’s inebriated subject (fig. 2). The text riffs on the whimsical dream-imagery of the photogram, connecting the celestial and terrestrial, the remote and mundane.

These themes in White Shadows run throughout Hager’s work as a whole. Indeed, the book may be read as a kind of culmination, marking the end of her four-decade exploration of camera-less photography. The title references Hager’s name for the complex monoprints she made by directly placing objects on light-sensitive paper. When exposed to light, the areas of paper obscured by objects remain white, while the negative spaces darken. Hager’s titular phrase highlights the inverted shadow-effect of this process and hints at a deeper interest in the medium’s capacity to confound natural order and codified systems of meaning.

Hager’s phrase figures in the title of the Harvard Art Museums’ ongoing exhibition White Shadows: Anneliese Hager and the Camera-less Photograph curated by Dr. Lynette Roth, Daimler Curator of the Busch-Reisinger Museum at the Harvard Art Museums. The show is among the first to focus on Hager’s photograms, which have been largely left out of the historical record due to the loss of her early work in the 1945 Dresden bombing and her later eclipse by male contemporaries. In addition to a copy of White Shadows, the exhibition displays twenty-nine of Hager’s photograms dating from the 1940s–1960s. These works appear alongside other photograms by nineteenth and twentieth-century scientists and artists, positioning Hager as a key figure in the medium’s history.

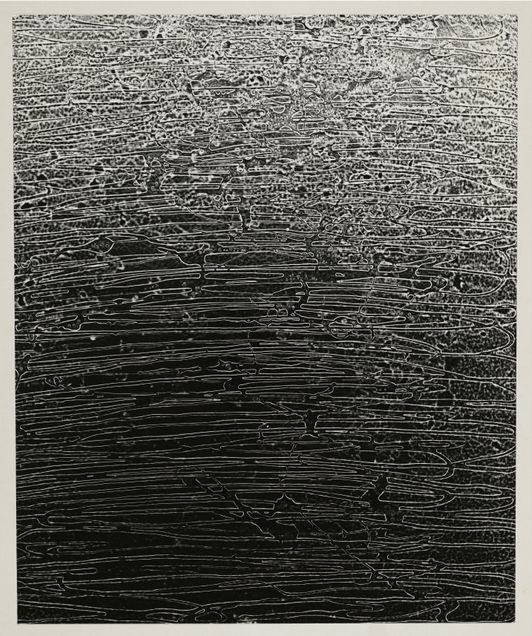

The exhibition also features the work of avant-garde artists such as László Moholy-Nagy and Man Ray, who popularized the use of photograms in the 1920s. While Hager did not know the two personally, she encountered their work through publications such as Moholy-Nagy’s landmark book Painting, Photography, Film (1925) and articles on photograms in the popular women’s magazine Uhu. Although inspired by these artists, Hager’s photograms look very different. Moholy-Nagy and Man Ray both produced images with strong figure-ground relationships and centralized compositions, as opposed to Hager’s dense, overlapped patterns and compositions that extend to the edges of the picture plane, making it hard to distinguish top from bottom. For example, Endless Chain II is displayed in the gallery with a horizontal orientation while it is reproduced vertically in White Shadows (fig. 3). Other instances of this all-over style include Compacted Structure, which presents a stack of frenetically oscillating lines (fig. 4, 1962).

The intricate yet expansive structures of Hager’s photograms signal another source of inspiration besides the avant-garde. Between 1922 and 1924, Hager worked as a technical assistant in the science of wool manufacturing. These years spent examining the thatched fibers of wool through a microscope provided Hager a visual vocabulary full of tactile nuance, sensitive to qualities of translucency and opacity.

Picking up on this scientific dimension of Hager’s work, the Harvard exhibition connects her to nineteenth-century pioneers of camera-less photography, including British botanists Anna Atkins and Ella Hurd, whose work is also on view. These early photographers created cyanotype photograms by placing plant specimens on paper coated with a photosensitive chemical mixture known for its blue color. The stunning silhouette images of ferns, seaweed, and other flora functioned primarily as scientific documents. Although Hager was not aware of these predecessors and did not use the cyanotype printing process, the comparison serves to foreground Hager’s scientific background and situate her in a lineage of women who created innovative photograms at the fringes of scientific and artistic developments.

This contextualization frames another ambition of the exhibition: to construct a history of the photogram emphasizing women’s contributions. This is an exciting revision, yet it competes somewhat with the show’s primary focus on Hager’s work. As a result, certain facets of her practice are underplayed, such as the relation between her poetry and photograms. Though White Shadows: Anneliese Hager and the Camera-less Photograph presents Hager still somewhat in the shadows of canonical “masters” of the photogram, her work emerges as something unique, that speaks as much to Hager’s unique vision as to the history she represents.

____________________

Renée Brown is a PhD student at Boston University where she studies twentieth-century American visual and material culture with a focus on the history of photography. Her work on these topics engages questions of epistemology and representation, considering the different forms of knowledge shaped through text and image.

“Bloody Vestiges” Out of the Night: Racialization and Adolphe Yvon’s Genius of America

by Elizabeth Mangone

At the end of the Civil War in 1865, formerly enslaved Black Americans had a burgeoning hope to receive the rights which were promised by the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution. Yet, despite the emancipatory purpose of the Civil War, inequality persisted in legal, cultural, and social spheres. One manifestation of this inequality in the post-Civil War era is the racial stereotyping of people of color. This legacy of racialized stereotyping is also visible in art made in or about the United States. Genius of America by Adolphe Yvon (1817–1893), also called The United States of America, is an allegorical painting commissioned by the Irish-American businessman Alexander Turney Stewart (1803–1876) which commemorates the end of the Civil War and the emancipation of enslaved people in the United States (fig. 1).1 Despite its message of liberation, its depictions of white people and people of color differ, with Black Americans relegated to the roles of “bloody vestiges” emerging from a war-torn “night.”2 Although Adolphe Yvon was an important painter in his time with connections to the highest levels of the second French imperial court, this painting, and his oeuvre more generally, remain largely unstudied in contemporary literature.3 While Genius of America was surely meant as a celebratory image of peace and emancipation, it reveals racial biases that were still present in the post-Civil War period and exhibits white anxieties over the process of emancipation and integration. Yvon’s strategic contrast between dark and light, and between Black and white figures, places newly freed Black Americans in a position of reliance on their white counterparts who metaphorically guide them out of the shroud of night and into the daylight of the newly reunited republic.

Yvon was a French Academic painter most known for his battle paintings, which include depictions of the Crimean War, Marshall Ney’s retreat from Russia, and the Battle of Solferino.4 He was born in Eschwiller in 1817, completed his schooling in Paris, and then traveled to Le Havre in 1834 to study painting under the tutelage of M. Ochard. He later joined the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris as a student of Paul Delaroche.5 Much of his early work was religiously themed, but he began composing historical scenes around 1846 when he completed “Battle of Koulikowo” on a trip to Russia.6 Yvon soon gained a reputation for Academic painting, and he won multiple medals, earned induction into the Legion of Honor, and served as a professor in the École de Beaux-Arts from 1863 to at least 1883.7 The use of allegorical figures, especially as overtly as in Genius of America, is not singular in Yvon’s known oeuvre, but it is a somewhat unusual occurrence. However, the depiction of current events, especially those relating to war, is typical of Yvon.

Genius of America was one such work that embodied Yvon’s painterly interests, which also manifested as an interest in the American Civil War. Alexander Turney Stewart, a Scots-Irish entrepreneur, commissioned the painting after viewing a sketch which Yvon made for an allegorical painting of the Civil War depicting what Henry Jouin called the “reconciliation of the North and the South.”8 While at this point it is unknown if Yvon ever visited the United States, it is possible that he was exposed to the country through the 1867 World’s Fair in Paris. The United States won several awards for advancements in technology and the arts at the fair and would surely have left the impression of a nation that was ready to leave behind its war-torn past in favor of a bright and advanced future.9 Stewart also served as the Honorary Chairman of the United States Commission to the 1867 World’s Fair; this event may have been where the two first met.10

While the exact circumstances of Stewart’s acquaintance with Yvon are not yet known, when Stewart’s collection was auctioned in 1887, it included multiple paintings by the artist. Genius of America is the only known commission as well as the only painting which Stewart owned of Yvon’s that addresses an American subject.11 Stewart was an Scots-Irish immigrant turned American business tycoon who sold dry goods and textiles. He immigrated to the United States at the age of sixteen and proceeded to build a business empire that began in New York, but ultimately spanned across both the United States and Europe.12 He belonged to a group of Irish protestants who originally came to Ireland from other parts of Europe, but by the mid-nineteenth century would have identified themselves as Irish.13 By the time he died in 1876, his business and estate were worth at least $50 million.14 Stewart’s relationship to the Civil War and the institution of slavery is debated. Art historian Hugh Honour claims that Stewart had connections to Southern planters which made him resistant to the emancipation of enslaved people up until the Union began purchasing their blankets and uniforms from his business.15 However, Michael Klepper and Robert Gunther, in their book The Wealthy 100: From Benjamin Franklin to Bill Gates — A Ranking of the Richest Americans, Past and Present, claim that he sold all the uniforms at cost, which would, instead, suggest that he supported the Union’s war effort against the Confederacy.16 Regardless of Stewart’s political leanings, he commissioned this painting from Yvon, as well as a mural-sized version of the work completed in 1870, which commemorated the end of the war. The mural was purportedly too large for Stewart’s private gallery, and so it hung in the ballroom of the Grand Union Hotel in Saratoga Springs, New York.17 Stewart’s ambiguous relationship with the Civil War may be reflected in Genius of America, as it shows both a nation reconciled after the Union’s victory and one still affected by the shadow of war. The painting also reinforces racial stereotypes, such as paternalism and white morality, which were used both to justify slavery and to call for abolition.

Although the title Genius of America suggests a unified Republic, contrasts between day and night, and light and dark, enhance differences between groups of people even as the painting celebrates the end of the Civil War (fig. 1). The tone of the center and left side of the painting is celebratory and the allegorical figures are highly classicized, suggesting both the joy of a newly found peace and a tying of the newly reunited American Republic to the roots of democracy. The composition is centered on two figures standing on a lion-driven chariot: Liberty, dressed in white and holding a mathematical tool which associates the figure with logic and reason, and Wisdom, dressed in green and wearing a breastplate decorated with a Medusa figure, implying a connection with Athena or Minerva. Around them stand women signifying each of the newly reunited thirty-four states of the Union, as evidenced by the architectural crowns they are wearing and the state abbreviations present on some of the crowns. At left are wagons of white figures with farming tools, identified as immigrants in Yvon’s 1870 description of the mural-sized copy of this painting.18 The identification of these figures as immigrants may reference Stewart’s own status as an Irish immigrant. The figures in the left register are, through the use of light and positioning, clearly associated with progress and the United States’ future. Their immigrant status therefore ties the future of the nation to immigrant populations made up of people like Stewart.

In contrast to the brightness of these scenes, the right register of the composition is shrouded in darkness and set against a red-skied battlefield with bodies still hanging from the gallows. This part of the composition is mainly inhabited by newly emancipated Black Americans, but also features Indigenous people at the back of the crowd. The darkness of the right register is oppressive, with only small highlights of light falling upon the faces of specific figures as they turn towards the center of the work. The band of red sky calls attention to the battlefield, indelibly linking the people before it with the aftermath of war. This association with darkness, night, and war depicts people of color as unmodernized and violent. In the upper right corner white figures on horseback are fighting off monsters, including a Medusa-like figure. A statue of George Washington, which is being presented with olive wreaths by devotees, overlooks the scene. The figure of George Washington associates the right side of the composition with America’s past, and his gaze conspicuously turns towards the center of the painting and the nation’s metaphorical future rather than back at the Black and Indigenous figures emerging from darkness.

The racialized tropes on display in Genius of America are especially apparent when the figures on the right side of the composition are compared to those on the left, a difference enhanced by Yvon’s use of light and shadow. In his 1870 description Yvon wrote, “On the right the bloody vestiges represent the past…From this night emerge the populations of color, from the Indians whom the light begins to fall upon to the Blacks, whom the whites raise, moralize and free.”19 By using the word night rather than darkness Yvon implies not only that people of color are without the illumination of wisdom, morality, and liberty, but also that this lack of illumination will, just as the night does, come to an eventual end. However, the painting also implies that this end will not be brought about by the Indigenous and Black Americans, but rather by their white contemporaries. Here Yvon suggests that Black and Indigenous people are helpless in the face of the night and need the assistance of morally righteous white figures to join the metaphorical day. By contrasting the extreme darkness of the metaphorical night with light encroaching from the left—brought by the white Europeans and allegorical figures—Yvon places people of color in a helpless role. He also reinforces paternalist ideologies and the trope of Manifest Destiny, which dictates that white Americans are divinely ordained to explore and settle the United States. These ideas rely on an otherized counterpart, such Black and Indigenous people, for their existence.

Yvon presents another contrast between the right and left registers of the painting with the inclusion, or lack thereof, of tools and implements of technology. The right register of the image is noticeably free from these features, with the only exception being the spears held by two Indigenous men even deeper in the dark night than the Black Americans. These spears only serve to draw deeper connections between the Indigenous figures and stereotypes of violence, rather than implying a technological proficiency. The European immigrants, in comparison, are shown with farming tools, oxen, and wagons. The white soon-to-be Americans are active in the cultivation of their future, whereas the newly freed Black Americans passively wait for the future to reach them. This contrast is even more striking given that many, if not the majority, of emancipated people in the United States had been freed from forced labor in agriculture, and so would have been readily capable with the tools in the hands of the white Europeans.

The contrast between the European immigrants with farm tools and the Black Americans who possess no technology may also allude to European beliefs about the “civilizing mission” of colonialism. Despite Stewart’s habitation in New York, and his attachment to the United States more generally, he spent many of his formative years in Ireland.20 Given that both the painter and the patron of Genius of America were European, it is likely that this scene of the United States also reflects contemporaneous European ideas. The idea of Europeans having a duty to civilize, moralize, or educate non-Euro-American cultures and peoples has long been used as a justification for colonial enterprises.21 Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, modern science became increasingly important as a marker of civilization.22 The idea of science as a civilizing force is bolstered by the mathematical tool present in Yvon’s depiction of the allegorical figure of Liberty and the subsequent implication that the idea of liberty itself is reliant on Western reasoning. The omission of farm tools and any other markers of technological progress in the right register of the painting implies that Black and Indigenous people are not yet ready to join the civilized post-war nation. However, the arrival of the European immigrants with modern agricultural tools signals that they will bring civilization and technology to the country’s future.

In the view of some Europeans and Americans in the nineteenth century, people of color were not only less civilized, but also possessed less humanity. The contrast in poses between the white and Black figures may evidence this belief. Whereas the European immigrants stand straight-backed and celebratory, waving pieces of fabric and hats in the air, the Black figures are largely shown hunched over or in supplicatory poses. These wide-eyed and awestruck representations of people of color resonate in a passage purportedly from Yvon’s memoirs. In the passage, he tells the story of visiting a slave market at which he saw “a beautiful creature” with the “frightened eyes of a gazelle.” He describes the “bronze colored” person as leaning on their hands and implies that his first instinct was to call them their front legs.23 Slavery was made illegal in France twice. The first emancipation of enslaved individuals occurred in 1794 under the First Republic. However, Napoleon Bonaparte reinstituted both colonial slavery and the slave trade in France in 1802.24 The second abolition of slavery was passed by the provisional government of the Second Republic in 1848, when Yvon was 31 years old. Although Yvon lived in France after slavery had been made illegal, this story suggests that he still held the view that enslaved individuals were in some way subhuman.

Yvon’s use of contrasting poses is also vital to understanding the racialized tropes of paternalism and the white man’s moral duty present in Genius of America. One Black figure thrusts an infant upwards towards the center of the composition, as if doing everything they can to ensure the child can be as close as possible to the bright daylight of the future that emanates from the West, both metaphorically through connections to Europe and literally through the physical layout of the painting (fig. 2). In contrast to the uplifted infant, the white mothers hold their children calmly to their bodies. This juxtaposition implies that the Black mother figure feels that the infant would benefit from exposure to the light of the future and therefore the light associated with white immigrants. Another Black figure is shown bowed over and peering, enraptured, at a Bible held by a stoic white clergy figure. The paternalistic figure of the clergyman embodies Yvon’s description in Explication des Ouvrages of white figures moralizing Black figures, and implies that this moralization justifies racial stereotyping (fig. 3).25 The idea of enslaved people needing to be moralized is also connected to France’s attitude towards emancipation over the course of Yvon’s lifetime. In the midst of debates leading up to the second end of French colonial slavery in 1848, one of the bills passed to appease abolitionist voices granted 650,000 francs to the purpose of providing a moral education to enslaved people.26 The presence of the clergyman may also reference Stewart’s history with religion. Before he immigrated to the United States, Stewart studied to become an Anglican minister.27 The visual comparisons between the Black and white figures, which are bolstered by the visual contrast between dark and light, support the idea that while the white immigrants are active and forward moving, the Black figures are rooted in the past and thus require assistance and education in order to participate in America’s future.

A notable pair of figures in the right foreground visually embodies the idea of Black dependence. There, a white man supports a nearly nude Black man who is reaching, completely outstretched, towards the center of the painting (fig. 4). The man’s blue coat identifies him as a Union Soldier, one of the only specific visual allusions to the Civil War present in the work.28 The soldier’s face is calm, whereas the Black man’s expression is rapturous as he gazes towards Liberty and Wisdom. In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War and emancipation, the relationship between the soldier and the Black man may likely have been considered positive, or even progressive, by the white viewer as it showed a white man uplifting a freed slave. However, the contrast between the soldier’s steady support and the Black man’s desperate sprawl away from the dark night and towards the light results in an unequal dynamic. The white man is depicted as level-headed and calm even as he supports the Black man, invoking tropes of white paternalism and Black hyper-emotionality. These two figures distill the relationship between white and Black Americans proposed by this painting: while Black people may be free from slavery, they still rely on white Americans for hope, education, and support.

Yvon’s Genius of America celebrates the end of the American Civil War, but the allegory also suggests white anxiety in the wake of emancipation. The contrast between the well-lit, celebratory Europeans and allegorical figures and the awestruck people of color shrouded in the darkness of night shows how beliefs about racial inequality translated into the visual arts. In Genius of America, Adolphe Yvon’s invocation of the night is central to the relationship between white people and newly freed Black people. While Yvon imagines white immigrants as productive and secure in the light of day, he places people of color in the night, surrounded by and embodying tropes of spiritual corruption, ignorance, and helplessness. The painting claims to celebrate a united nation, the freedom of enslaved people, and the belief in a progression from the war-torn night of the antebellum era into the radiant hope for a postbellum future. Yet, in this progression, people of color are still firmly situated in the past. Genius of America reveals the contemporaneous reality that while emancipation might have been achieved, equality was far from realized.

____________________

Elizabeth Mangone is a first-year MA student in art history and archaeology at Washington University in St. Louis. She holds a BA from Furman University. Her research focus is broad ranging in European art with a special interest in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century abstraction.

____________________

Footnotes

1. Thomas B. Brumbaugh, “The Genius of America: Adolphe Yvon’s Remarkable Picture,” Southeastern College Art Conference Review 11, no.1 (Spring 1986): 9. Genius of America is likely not Yvon’s chosen title for the painting. The work seems to have been commissioned with the title The United States of America but was colloquially referred to as The Genius of America.

2. Unless otherwise indicated, translations are the author’s. Explication des Ouvrages de Peinture, Sculpture, Architecture, Gravure, et Lithographie (Paris: Charles de Morgues Frères, Imprimeurs des Musées Imperiaux, 1870), 392.

3. A. Augustin-Thierry, “Souvenirs D'un Peintre Militaire,” Revue Des Deux Mondes 17, no. 4 (October 15, 1933): 844–849. In this essay Thierry relays the story of Napoleon III posing for a battle painting in Yvon’s studio, showing that the artist was connected to the Emperor himself during the French Second Empire.

4. Eugène Heiser, Peintre de Batailles et Portraitiste: Adolphe Yvon (1817-1893) et les Siens (Paris: L'Imprimerie Hamann, 1974), 75.

5. Henry Jouin, “Discours Prononcé le 13 Septembre 1893 au Nom de d’École des Beaux-Arts en le Cérémonie des Obsèques du Maitre” (Paris: L’Artiste, 1893), 12–14.