news

Ties That Bind: Hairwork as Family Portrait in the Nineteenth-Century United States

by Victoria Kenyon

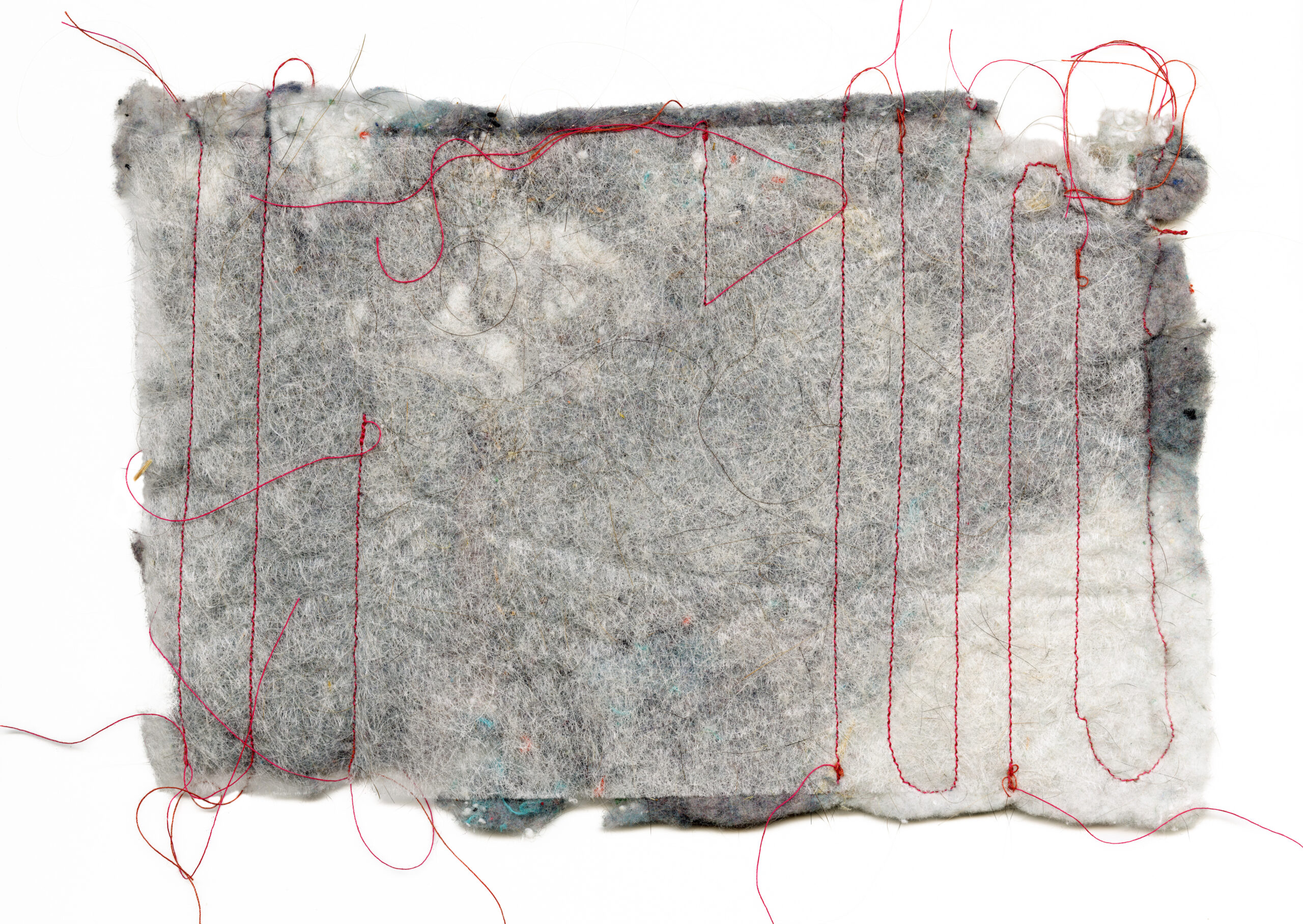

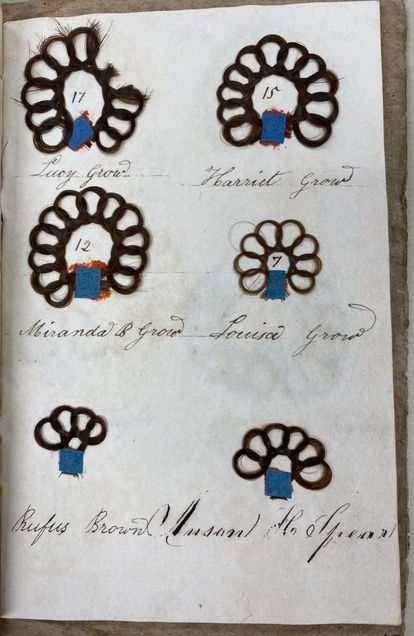

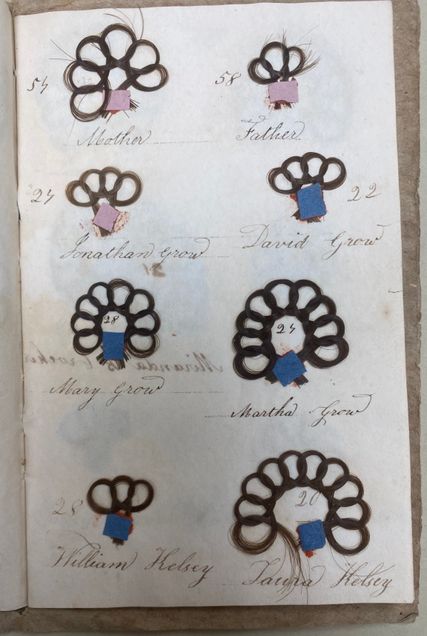

The young artist collected her central material, hair, from people both in and outside of her immediate family. Grow’s placement choices establish family connections and provide crucial context for the way we are meant to read her album. On one page, she depicts herself and her sisters in nearly-identical hair chains inscribed with each girl’s age and arranged from left to right in descending age order (see fig. 1). This arrangement suggests the format of the family tree, the botanical iconography of which goes back to the Tree of Jesse motif in Christian Medieval and Early Modern Europe.5 Such documents and other genealogical records, including family registers, were historically important to establishing familial connection. Karin Wulf has examined the religious and political implications of familial genealogy in British America, noting the reflection (and indeed support) of white, patriarchal systems of inheritance in the practice of listing one’s family members and recording events such as marriages, births, and deaths in record books and family bibles.6 As in hairwork, there was an element of sentimentality in the emotional connection evoked through documenting one’s family, as well as a didactic quality. Though apparently not a necessary component, some such documents also included physical likenesses of individuals alongside names, as evidenced in an 1875 Vermont marriage certificate (fig. 3).

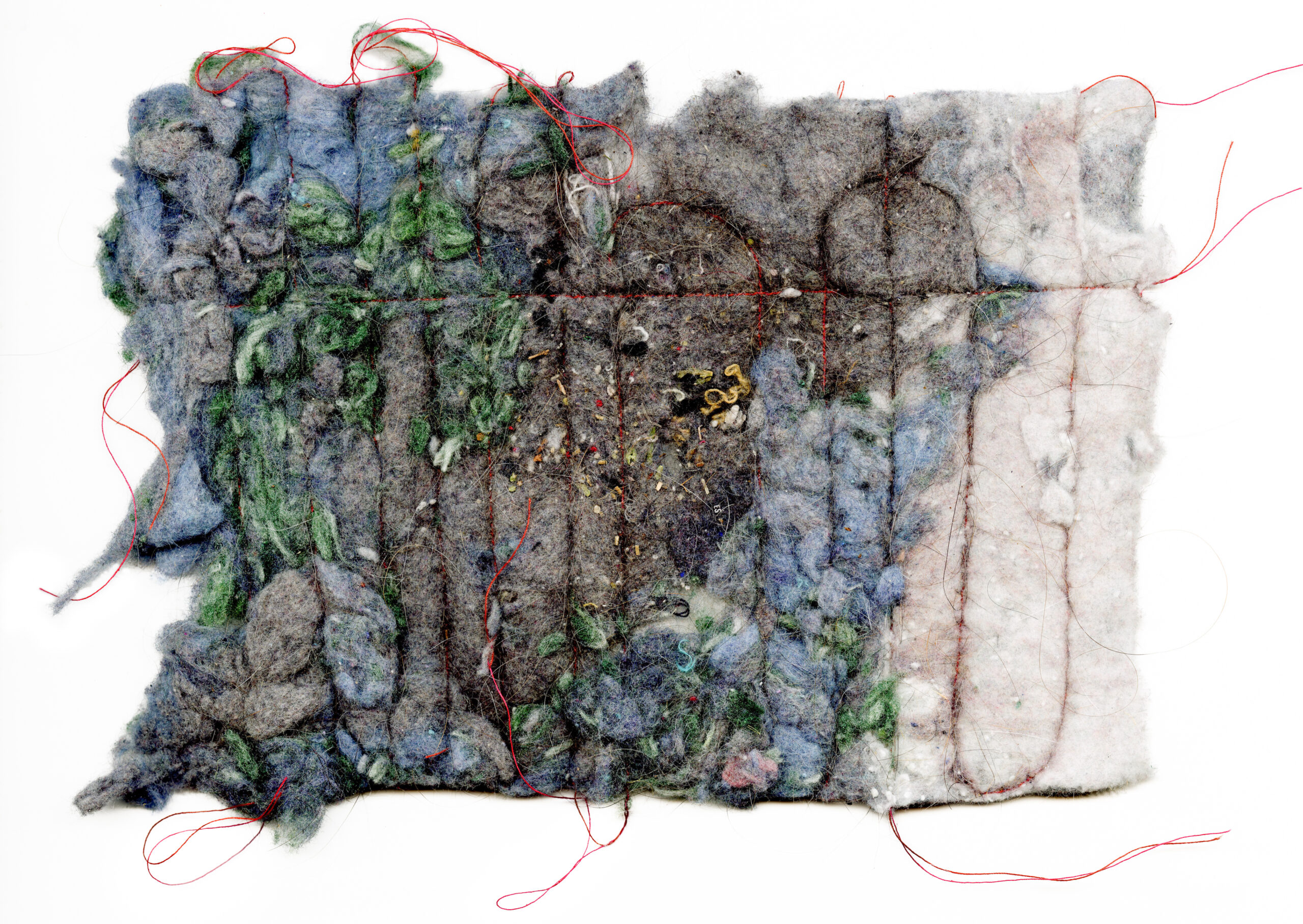

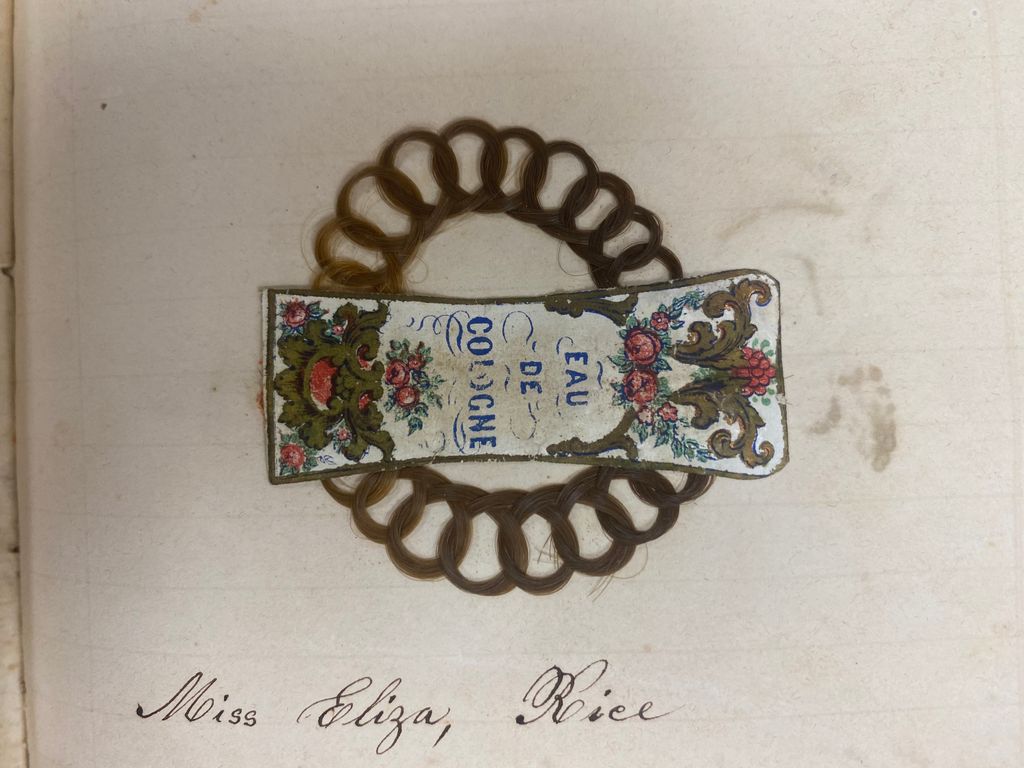

Grow’s medium does not provide as direct an image of a person as would a photograph, but her portraits reveal some facets of appearance that photos or other media could not, including the full tonal ranges of a person's hair. There may have even been an olfactory component to the objects; another nineteenth-century album, made by Louisa Rice of Paradise Township, Pennsylvania, included a perfume label in a hair portrait of the artist’s sister (fig. 4). Coupled with the fact that period advice guides directed young women to perfume their hair, this suggests that Louisa Rice may have applied the perfume to which the label belonged to that hair portrait, and Grow may have similarly scented her objects to strengthen the connections between individual and portrait.7 Grow also creatively shows physical differences in the sisters’ portraits in figure 1; the youngest’s (Louisa, 7) is noticeably smaller. Grow continually groups family members together in her album. Another page depicts her parents and some of their children, though Lucy herself is missing; the Kelseys, included at the bottom of the page, may have been Grow family cousins, as they shared a house with the Grows (fig. 5).8 Again, the arrangement of the hairwork portraits, with the mother and father at the top of the page and their children below, suggests a genealogical record, albeit an incomplete one.

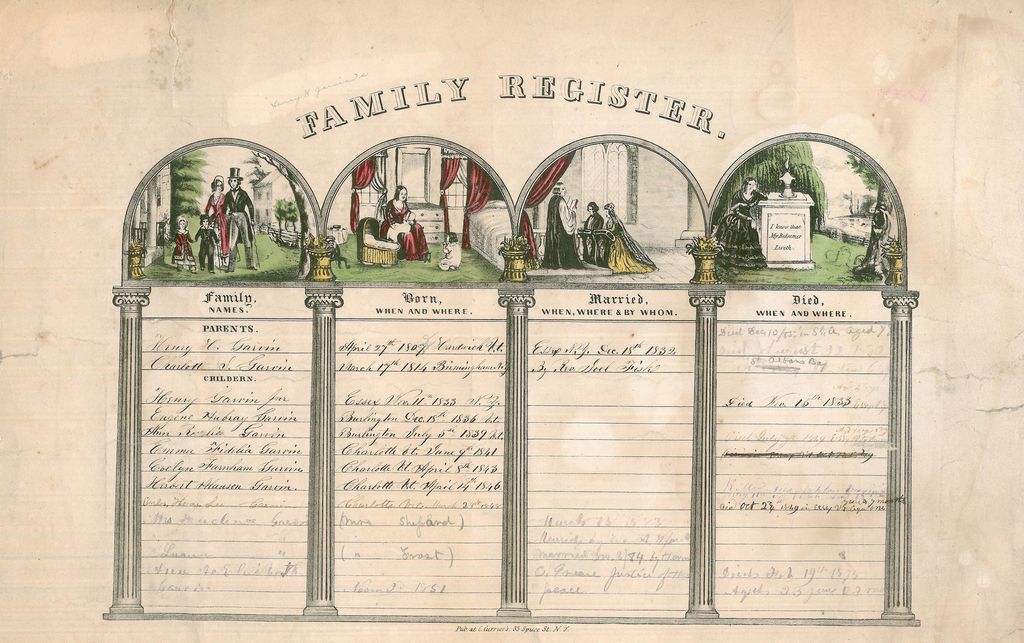

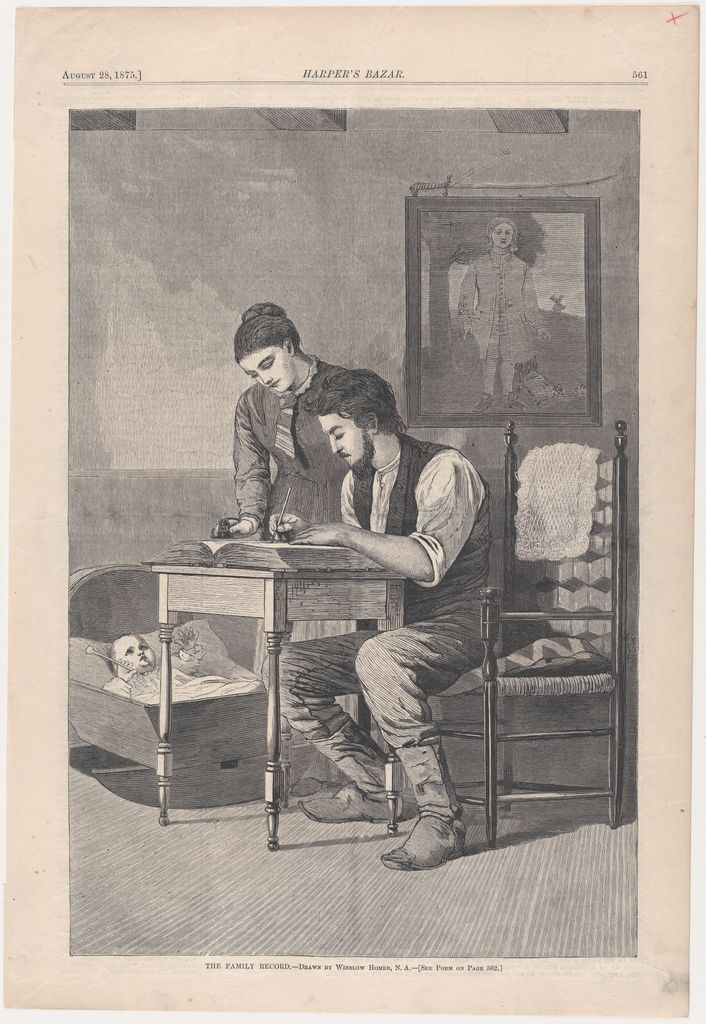

Another nineteenth-century Vermont family, the Garvins, recorded their members in a mass-produced family register showing the parents listed above the children (fig. 6). This lithograph includes illustrations of a typical white family: mother, father, son, and daughter. In one vignette, the dutiful mother tends to her children, and in another, she gazes at her husband, who does not look back at her. This imagery further demonstrates the patriarchal nature of genealogical practice, as described by Wulf. This patriarchal family record-keeping imagery appears in popular media too: an 1875 print after Winslow Homer from Harper’s Bazar shows a family in the act of writing down their history. The bearded white man records a new addition to the family lying in a cradle at his feet in a large book, his wife dutifully holding the ink pot steady as he makes his marks while the man’s ancestor watches from a painting above (fig. 7).9 Herein lies the tension that Grow’s album produces. Unlike the Garvin register or the Harper’s print, this woman does not just play a supporting role in providing or recording a family image. Grow is the maker of her album’s portraits, and the inscriber of her family’s names.

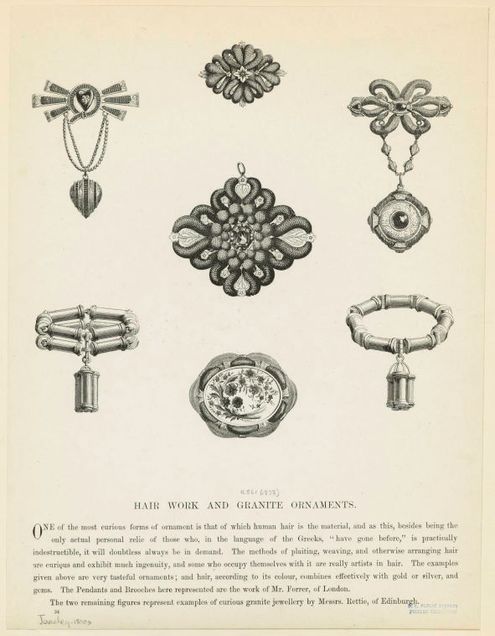

Most early professional hairwork makers were white, middle-class men trained as jewelers or metalworkers who fulfilled commissions to produce brooches, pocket watch chains, and other wearable articles (fig. 8).10 By the mid-nineteenth century, some women produced hairwork in their own homes, effectively cutting out the middleman to make objects directly from their family members’ hair. Interested crafters could reference a variety of texts, including Mark Campbell’s Self-instructor in the Art of Hair Work (1867) and articles in Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine. Campbell claims his book “will prove an indispensable adjunct to every lady's toilet table.”11 Likewise, Godey’s assures “the fair reader” need not “be alarmed…I do not intend to frighten her with a long list of expensive machinery and tools.” Instead, she could use tools common in textile crafts, such as scissors and knitting needles.12 It is hard to know if Grow would have consulted sources like these, as the images in both of these texts look quite different from the objects she produced, and both were published decades after the initial date in her book. Still, these sources show how middle-class women learned this distinctly feminine-coded craft.

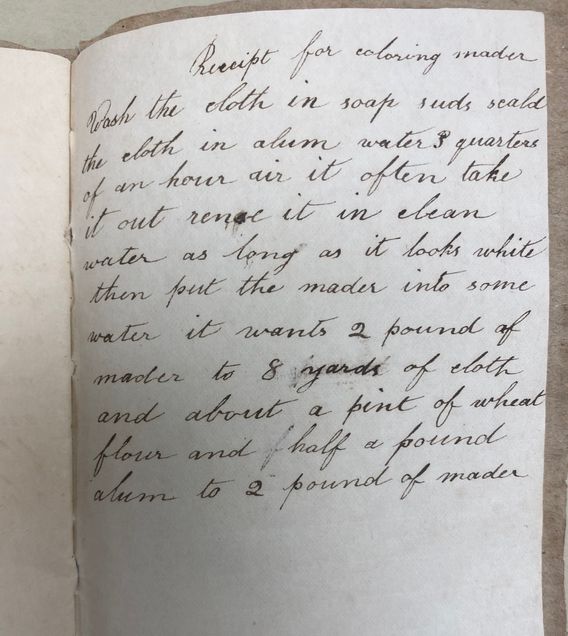

Grow would likely have seen her album’s connections to other domestic arts; she even included a recipe for madder root fabric dye, which could be used for textiles, in the back of her book (fig. 9). This further links her hair album with so-called “women’s work,” or those domestic crafts long undervalued in art criticism and scholarship.13 Grow was probably also intimately aware of hair as an expression of gender, which was integral to the nineteenth-century white woman’s image-fashioning, as evidenced in period advice guides.14 Domestic labor and hair were markers of feminine identity, and hairwork combined both of these forms of gender expression. Thus, it is even more noteworthy that Grow and other domestic hairworkers used the craft to depict not only themselves but also their female and male relatives. One wonders if the young artist saw irony in her use of hair, so often employed to display a woman’s status, to depict a brother or cousin instead.

Writing about salvage arts, feminist scholar Elaine Hedges argues, “in seeking to understand more fully the everyday lives of nineteenth-century women, we must piece together scraps as they once did.”16 The archive does not preserve the full story of Grow’s life, nor that of her family. The traces of the Grows I have managed to find are owed to the genealogical connections revealed in Lucy’s pages. She pieced together her family and community members’ hair in her books, and we can now learn about their lives through her work. As I have made clear, these were not neutral or entirely innocent practices: in creating these hair portraits, Grow promoted a family history that, while subversive in some ways, fit firmly within white, patriarchal systems. Albums like hers provide tremendous potential for further considerations of collaboration, women’s work, and the many other meanings woven into hairwork. As I have argued, they also expand our views of gender and family image-fashioning in the nineteenth-century United States.

____________________

Victoria Kenyon is a Curatorial Track doctoral student in the Department of Art History at the University of Delaware. Her research interests include the history of religion and the supernatural in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American art, and she is especially fond of exploring the macabre in visual and material culture.

____________________

1. The original date listed for this album in the Eberly Family Special Collections Library records was c. 1820, but the 1870 census record shows that Lucy (by that time married and with two children) was born in 1822. In the album, she notes her age is 17. U.S. Census Bureau, “1870 United States Federal Census,” National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, accessed through Ancestry, images reproduced by FamilySearch.

2. See Helen Sheumaker, Love Entwined: The Curious History of Hairwork in America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007).

3. Marcia Pointon, “‘Surrounded with Brilliants’: Miniature Portraits in Eighteenth-Century England,” The Art Bulletin 83, no. 1 (Mar. 2001): 61; Robin Jaffee Frank, Love and Loss: American Portrait and Mourning Miniatures (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), 13; Sheumaker, Love Entwined.

4. Karen Halttunen, Confidence Men and Painted Women: A Study of Middle-Class Culture in America, 1830-1870 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982), 58-60.

5. Heather Wolfe, “Where do Family Trees Come From?,” Folger Shakespeare Library, February 21, 2014. https://www.folger.edu/blogs/collation/where-do-family-trees-come-from/.

6. Karin Wulf, “Bible, King, and Common Law: Genealogical Literacies and Family History Practices in British America,” Early American Studies 10, no. 3 (Fall 2012): 482-86.

7. Emily Thornwell, The Lady’s Guide to Complete Etiquette in Manners, Dress and Conversation, in the Family, in Company, at the Pianoforte, the Tables, in the Street, and in Gentlemen’s Society. Also a Useful Instructor in Letter Writing, Toilet Preparations, Fancy Needlework, Millinery, Dressmaking, Care of Wardrobe, the Hair, Teeth, Hands, Lips, Complexion, Etc. (Madison, WI: T.T. Rustone, 1887), 33-36.

8. U.S. Census Bureau, “1860 United States Federal Census,” National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, accessed through Ancestry, images reproduced by FamilySearch.

9. Though outside the scope of my analysis here, Shawn Michelle Smith’s interrogation of racial family imagery is essential to my reading of this image: “‘Baby’s Picture is Always Treasured’: Eugenics and the Reproduction of Whiteness in the Family Photograph Album,” Yale Journal of Criticism 11, no. 1 (Spring 1998): 197-220.

10. Sheumaker, Love Entwined, 34-35.

11. Mark Campbell, Self-Instructor in the Art of Hair Work, Dressing Hair, Making Curls, Switches, Braids, and Hair Jewelry of Every Description: Compiled from Original Designs and the Latest Parisian Patterns (New York: M. Campbell, 1867), 6.

12. “The Art of Ornamental Hairwork,” Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine 58 (February-April, 1859): 153.

13. See Lucy Lippard, From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women’s Art (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1976).

14. Thornwell, Lady’s Guide to Complete Etiquette, 33-36.

15. Sheumaker, Love Entwined, 26.

16. Elaine Hedges, “The Nineteenth-Century Diarist and Her Quilts,” Feminist Studies 8, no. 2 (Summer 1982): 298.

Re-Fuse: The Macro-Ecologies of Microfiber Waste

by Adelaide Theriault

Figures 1-7. Adelaide Theriault. Sediment and Erosion (1-7) (2023). Digital scan of laundry lint, hair, skin, dust, microplastics, natural fibers, cotton thread, dryer sheets, various other debris from laundered fibers. 34 x 24 in. each (86.4 x 61 cm). Images courtesy of the artist.

I think often of dust, of erosion, and of the ever-changing contents in contemporary soil bodies. The fabricated separation between humans and their co-inhabitants is a tool for the upkeep of capitalist extraction that shelters us from the vibrant reality of our ecological presence—a presence that exists regardless of our intentions and, frequently, in spite of our perceptual limitations. I am reminded of this human presence and of my own roles within my ecological webs when I witness squirrels building homes within the engine of my father’s broken-down work truck, or when I see birds nesting in hollow shop sign letters. I see the active role that I play in the grasses whose seeds disperse by clinging to and falling from my clothes. I am interested in the ecological, social, and geological significance of matter such as laundry lint, concrete, and grasses—and I believe that any and all forms of matter can act in their place as a lens for eco-critical research.

Laundry lint documents and communicates the social and ecological memory held within its fibers. The layers of lint that build up inside the dryer screens at my local laundromats are reminiscent of the geological diagrams of my childhood textbooks, in which the layers of soil and rock are visually isolated, acting as timestamps. As I collect the lint from loved ones and laundromats, I learn about the habits and lives of the people I share space with, through the debris of forgotten receipts and felted sheets of their pets’ hair. I think of laundry lint as a soil itself—not only visually, but through its physical makeup and its relationships to greater ecological webs. Laundry lint is a tangible artifact of contemporary textile culture and of the slow erosion of matter. The laundering and manufacturing of synthetic textiles, along with the conception, recycling, and discharging of wastewater, creates conditions for the movement of microplastics across Earth’s surface. As these microplastics accumulate in soils, they entangle deeply into new ecological webs, enacting gradual change within the bodies of the plants, humans, and non-human animals that consume them.

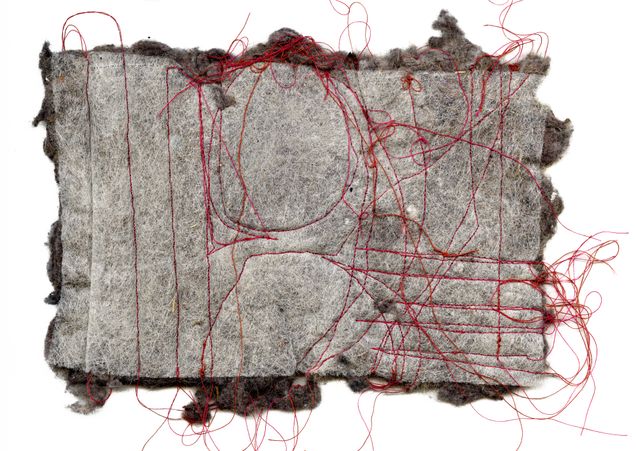

In recognition of these webs, and of the deep-time cyclical lives of microfibers—from microplastics to animal fibers to cotton—I embroider collected lint on dryer-sheet backings. These topographical maps created from lint and thread draw inspiration from the familiar imagery of urban and agricultural grids I have seen from airplanes and on satellite maps. On the reverse side, however, the threads that bind the matter together become tangled, pouring out off the edges of their photographic containers, as can be seen in Sediment and Erosion (Composition #8 of 8) (fig. 8). I am interested in calling attention to the subsurface of the ground, of memory, and of our perception. These threads point to the entangling interspecies relationships of subterranean life—fungal, animal, microbial, electrical, and botanical. These relationships are now in collision with anthropogenic conduits for the transport of water, information, power, and oil along with their resulting fields of debris. I am driven and creatively stimulated by the reorientation that occurs in me in order to understand my relationship to the subsurface, because it requires me to deprioritize visual ways of knowing the world. This way of thinking about plastic pollution occupies a long-term, non-linear timeline. I felt moved and torn by the recognition that this tiny plastic material—one with origins deep beneath Earth’s surface where it was extracted as fossil fuels—could be submerged once again in the soil, yet be so unable to break back down and return home.

Figure 8. Adelaide Theriault. Sediment and Erosion (8) (2023). Digital scan of laundry lint, hair, skin, dust, microplastics, natural fibers, cotton thread, dryer sheets, various other debris from laundered fibers. 34 x 24 in. ( 86.4 x 61 cm). Image courtesy of the artist.

Plant communities, too, have networks of conduits for the transport of nutrients, water, and information that are being increasingly intersected by microplastics. Some plants’ roots can be inhibited from absorbing all that they need by plastics. Other plants may absorb dyes and plastic-derived toxins, transporting them through their roots and stems to their leaves and fruits. Plants bear much of the current brunt of microplastic dispersal, but they are not simply passive victims or witnesses to this pollution. The pollution-induced stress that many plants face is a result of their capacity to enact physical, chemical, and restorative change. Plants are often used in constructed wetlands to clean sewage and wastewater because of their key role in the ecosystems that host beneficial algae and micro-organic decomposers. Our familiar desert and prairie grasses, too, play restorative roles by holding and securing bodies of soil, preventing particulate erosion and dispersal.

In response to my understanding of these plant and pollutant relationships in contemporary soils, I planted grass seeds local to Albuquerque’s high-desert ecosystems in beds of laundry lint. The lint held water and provided nutrients for the grass in the form of the dead skin cells, decaying natural fibers, and hair amidst the synthetic matter. The grass, in exchange, grew to hold the lint securely in its roots, protecting it from erosion.

The grasses lived only for a short season before I left them to dry, because I realized that what I was doing was asking them to sacrifice themselves to plastic toxicity in order to hold this symbol of repair. Images 1 and 2, in the series From Old Growth, commemorate the relationship between the grasses and lint, presenting a feeling of hope, repair, and regrowth from refuse (figs. 9 and 10). They also serve as a symbol of mourning for the irreversibility of the pollutant ripples that unfurl from the extractive systems that define the Capitalocene, an alternative designation for the current epoch that emphasizes capitalism’s central role in driving environmental degradation and societal inequalities.

Figures 9-10. Adelaide Theriault. From Old Growth (1 and 2 of 7) (2022). Digital scan of laundry lint, water, sunlight, native grasses. 36 x 24 in. each (91.4 x 61 cm). Images courtesy of the artist.

This moment within my larger creative research practice presented to me a reminder of the necessity of a shift away from a strictly anthropocentric worldview—one that reduces non-human matter to passive roles. When we refuse this authoritative, extractive perspective in exchange for one that recognizes the place-making, sensing, and restorative capacity of all parts of this more-than-human world, we have an opportunity to re-fuse severed ecological relationships.

____________________

Adelaide Theriault is a trans-disciplinary artist currently based on Tiwa lands in so-called Albuquerque, New Mexico, where they are working towards an MFA in Sculpture and Art and Ecology at the University of New Mexico. Adelaide works sculpturally, photographically, and performatively with found materials and site-specific sensory inquiry to nurture a practice of ecological research. Adelaide has shown in exhibitions across New Mexico and Texas, and was most recently nominated as a 2022-2023 SITE Scholar at SITE Santa Fe.

____________________

Unraveling the Artistic Threads: An Interview with Snigdha Tiwari

by Sakina Ahmad

Snigdha Tiwari is a Delhi-based artist whose work weaves together a rich tapestry of creativity and personal narratives. Known for using textiles and fabrics in her art, she has been featured in prominent group exhibitions like Immerse (2022), The Cadence of Free Fall (2019), and Art Asia (2018). Her artistic growth is further highlighted by residencies at both 1ShanthiRoad’s Space 118 in Bengaluru and the Cona Foundation in Mumbai. Tiwari, a finalist for the 2022 Emerging Artist Award South Asia, holds a Master's of Visual Art in Painting from Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda and a BFA from Delhi University’s College of Art. In this interview, she opens up about her artistic journey, inspirations, and methods of using textiles, fabrics, and threads as a medium for self-expression.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity; for the full audio recording, please refer to the bottom of the page.

Can you tell us about your early influences and your transition into textiles?

I began my artistic journey with painting, a path set by my parents when they handed me a brush. However, I had always been intrigued by sewing, viewing it as a utilitarian activity. It wasn’t until my college years, when I delved into the works of renowned artists worldwide, that I discovered the potential of threads and fibers as a medium of artistic expression. This artistic awakening led me to explore the diverse possibilities of these materials; that is where it all started.

One pivotal influence during my academic journey was Mrinalini Mukherjee, an Indian art practitioner who redefined weaving from a craft into a tool for fine art. Mukherjee’s sculptural artworks, often inspired by deities and the natural world, shaped my perception of textiles as an artistic medium. I was also looking at Sheila Hicks, an artist who crafts large-scale sculptures and tapestries from various threads. This is when I really started believing in the sculptural possibilities of textiles (fig. 2).

How does your background in painting influence the way you capture organic essence in your art?

My journey from painting to textiles was driven by my fascination with the tactile nature and three-dimensionality of materials. I didn’t connect that way to any other type of painting because I didn’t enjoy them, and there was a kind of flatness to them. Materials like natural fibers or wool are profoundly tactile and have a body of their own, possessing characteristics that painting can’t replicate. My artistic process is a dialogue between myself and the materials I use, where sometimes the material takes the lead and at other times it’s guided by my artistic vision.

How have artists who explore deities, higher powers, and spirituality influenced your own creations?

My work draws inspiration from artists like Mrinalini Mukherjee, who has explored themes of spirituality, deities, and the interconnectedness of beings with the natural world. While I appreciate the spiritual dimensions in other artists’ work, my current connection is more with the inherent power and identity of the materials themselves. My spirituality lies in the respect and reverence I hold for the materials I use. I believe that even everyday materials like plants have stories, and my art aims to highlight these, respecting the essence of the materials as my form of spirituality.

Your project “Dearest” critiques digital identities and self-perception. Could you elaborate on how the theme of threads, along with the interconnectedness and unity found in textiles and woven materials, plays a role in this project?

“Dearest” is an ongoing project that I see as a constantly evolving narrative (fig. 3). It critiques digital identities and self-perception, embodying the concept that objects and materials hold a part of us, linking physically to our memories and experiences. This physicality stands in stark contrast to the digital world’s intangibility. “Dearest” is like a tree, with each artwork representing a branch connected to my life’s journey, evolving with my past and present experiences and the dynamic interplay of personal, social, and political influences in our lives.

The theme of “threads” resonates deeply with my artistic journey. The constant strand or the thread that runs through all these artworks is my personal interpretation of these experiences. This thread, whether altered or left in its authentic form, intertwines my narrative and artistic exploration. It mirrors my dedication to exploring the depth and possibilities of my chosen materials, while also addressing my personal concerns and interpretations. As I continue to unravel and reweave these threads, my art evolves into a dynamic tapestry, rich with my experiences, viewpoints, and ever-evolving artistic ambitions.

Could you describe your artistic process?

My artistic process involves a constant back-and-forth between myself and the materials I work with. At times, the materials themselves lead the creative process, inspiring the narratives I craft. Other times, I seize control to express my vision more directly. This process involves extensive experimentation, including manipulating materials and preparing them with techniques like dyeing, the Bhati technique, and knotting. I also incorporate a variety of materials, including papier mâché, synthetics, and organic materials to create diverse narratives.

Could you elaborate on the blend of synthetic and organic materials in your work and share your perspective on the impact of modern, synthetic-focused textile production on traditional practices?

I’m not extensively using traditional practices, but the materials I use, like a specific kind of hemp rope, are becoming rare due to the rise of synthetic rope production. This hemp, once native to India, is now dwindling. I use these ropes, braiding the fiber into rope entirely by hand, from extracting the fiber to producing the final rope. It’s a dying industry, but deeply local and rooted in Indian soil. I’ve also extensively used jute fiber, dyeing it in various ways to express my concerns and ideas. Additionally, I’ve worked with materials like wool and cotton, employing dyeing processes, including experimenting with pomegranate dye. This particular work creates an overlap of synthetic and natural dyes, serving as a satire of our lives, where organic materials are often overshadowed by synthetics. Even the jute fiber I use sometimes contains plastic, which I keep as it reflects our current reality. Through experimentation, I’ve faced many failures, but I’m eager to delve deeper into natural dyeing processes that are indigenous to India. My goal is to learn and preserve these traditional methods, which are at risk of disappearing (fig. 4).

What are your broader artistic philosophy and goals? What kind of experience or understanding do you hope viewers derive from it?

I think I’m in discovery mode right now, realizing that each of my works, deeply personal and significant, speaks about different aspects of myself. One particular work, Fish Slice, stands out vividly in my memory (fig. 5). It began with orange yarn on my frame loom, to which I added raw cotton fiber, contrasting with the processed wool I usually use. The outcome was astonishing, resembling the skin of a fish, and this piece holds a special place for me. It marked a turning point in my artistic journey, opening my eyes to the myriad possibilities and narratives inherent in the materials around me. This realization has encouraged me to dive deeper into storytelling through these materials, making Fish Slice not just a personal piece but also a catalyst for a more detailed and conscious exploration of my surroundings.

My main aim is to showcase the expressive potential of materials to audiences, often surprising them with the innovative ways materials can mimic textures like skin or hair. I focus on personal narratives, especially mental health concerns, and aim to raise awareness about issues like Seasonal Affective Disorder. Since weaving has been a therapeutic process for me, I would like to celebrate it and I would like to take it to people. I’m committed to bringing these personal and mental health narratives to a wider audience, using softer mediums like textiles to express themes that might not be as effectively conveyed through more rigid forms like stone sculpture. My goal is to reveal the unexpected possibilities of materials and discuss important topics through this unique approach.

What do you hope to explore more in your practice, and what do the next few years look like for you in terms of your artistic work?

One of my goals is to explore the scale of materials. Currently, I’m focusing on developing large-scale artworks and exploring the scale of materials. My future projects aren’t strictly defined, as my artwork tends to be immediate responses to my experiences. For instance, my project Black Rain critiques governmental policies and their short-sighted approaches to issues like acid rain and pollution, highlighting the cyclical nature of these problems. This project, among others, reflects my ongoing concerns. I’m also eager to learn more about dyeing techniques and to discover lesser-known materials and skills in different areas of India. Over the next two years, I see myself deeply engaged in experimentation, exploration, and learning from the resources around me.

Listen here for the full audio recording of the interview:

____________________

Sakina Ahmad is a communications professional with an MA in Art and Museum Studies from Georgetown University. She excels in marketing for artists and cultural institutions, merging design and writing to create meaningful content. Currently, she is the Assistant Manager of Marketing and Content at the American Alliance of Museums.

____________________

Cut With the Tailor Scissors: Hannah Höch’s Textile Designs and the Development of Photomontage

by Iris Giannakopoulou

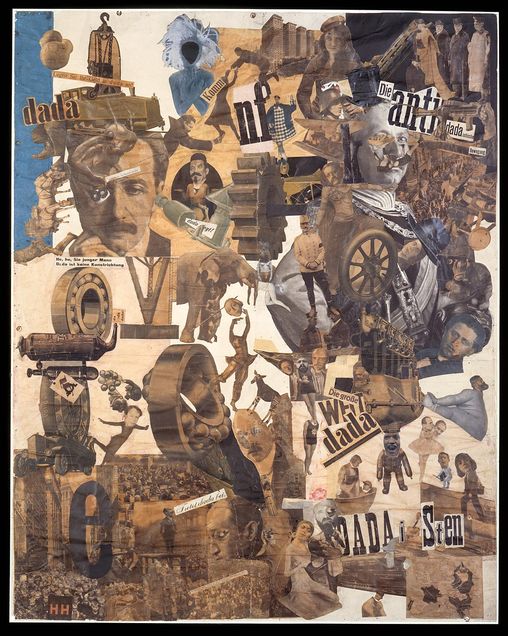

Hannah Höch (1889–1978) is best known for her participation in the Berlin Dada movement and her pioneering works of photomontage, collages made mostly or entirely from photographic reproductions. Her piece Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany, exhibited in the First International Dada Fair at the Otto Burchard Gallery in Berlin in 1920, stands as one of the most iconic images of this European avant-garde movement (fig. 1). Emphasizing her diverse background in handicrafts and the applied arts and her unique position as the only female member of the group, this essay demonstrates the influence of textile design on Höch’s photomontage practice. In doing so, it challenges prevailing modernist narratives of the late 1910s and early 1920s surrounding the development of the medium in association with male artists and with disruptive and virile connotations.

During the mid-1960s, American art critic and curator William Rubin called the development of photomontage “the most significant contribution” of the Berlin Dada and ascribed its invention to the group’s founding member Raul Haussman.1 The artist, however, was not “the first Berliner to hit upon the photomontage” as Rubin contended, or at least not the only Berliner.2 In fact, both Haussman and Höch, a couple at the time, discovered the powerful potential of photomontage during a summer trip to the island of Usedom in the Baltic Sea in 1918. There, the two came across a popular type of engraving at local homes and businesses, which involved collaging photographic portrait heads of local men who were away at war onto found torsos. These mementos had a distinct visual impact on the two artists who were already familiar with the photocollage posters of fellow Berlin Dada members John Heartfield and George Grosz.3 Since 1916, Heartfield and Grosz had been experimenting with collages made from photographic reproductions. Their works, however, were primarily geared towards creating provocative political statements and lacked the artistic qualities of these popular pictures. Upon their return to Berlin, Haussman and Höch began experimenting with the medium by clipping photographs from a variety of illustrated sources and mixing them to create new visual imagery that, as Haussman would later recall, “attacked the political events of the day with biting sarcasm.”4

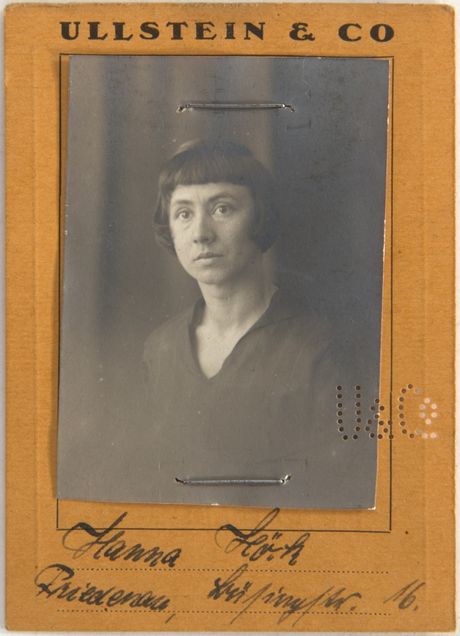

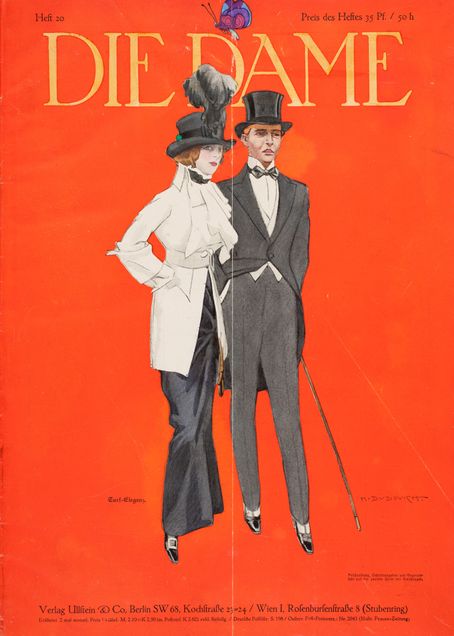

Höch was especially well-equipped when it came to harnessing the potential of the emerging medium. Unlike Haussman, who was formally trained in sculpture and painting, Höch came from the world of crafts. Before the war, she studied glass design and calligraphy at the Charlottenburg School of Applied Arts in Berlin, while in 1915 she transferred to the graphic and book arts program of the State Museum of Applied Arts. During her training, Höch begun to focus on embroidery, a craft that, as a woman, she had likely cultivated from a young age; she earned recognition for at least two designs that were subsequently featured in the Darmstadt needlework journal Stickerei- und Spitzen-Rundschau (Embroidery and Lace Review). With her training in graphic design and experience with embroidery, Höch secured a part-time position at Ullstein Verlag, one of Germany’s largest interwar-era publishing houses.5 Between 1916 and 1926, Höch worked three days a week at the pattern division of Ullstein (fig. 2). In this position, she was responsible for designing patterns for knitting, crocheting, and embroidering, and she created advertising vignettes and typographic layouts for magazines such as Die Dame (The Lady) and Die Praktische Berlinerin (The Practical Berlin Woman) (fig. 3). Höch’s responsibilities extended beyond design: she also oversaw the fabrication of these patterns, utilizing a range of techniques including cutwork, drawn- and pulled-threadwork, needle-lace, darned-filet, and embroidery.

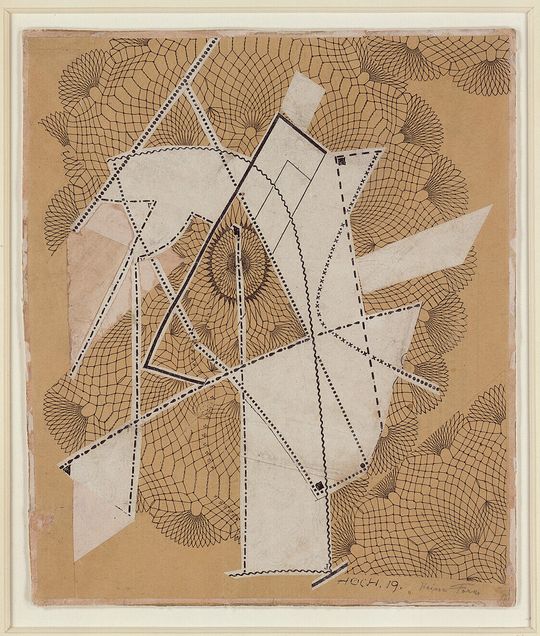

This diverse background equipped Höch with a wide range of technical and artistic skills that she was able to apply when creating her photomontages. Her experience in book and graphic design honed her ability to organize visual elements, text, and images into cohesive compositions within a limited space, effectively conveying visual messages. For instance, in Cut with the Kitchen Knife, the deliberate placement of a map depicting European countries that granted women voting rights at the bottom-right corner of the piece—the location usually reserved for the artist’s signature—subverts layout conventions, delivering a clear political statement about women’s empowerment. At the same time, Höch’s special attention to detail and careful consideration of color and texture can be attributed to her experience with embroidery, while the particular emphasis she puts on the outlines of her ‘cutout’ silhouettes is reminiscent of the figures in textile pattern designs as vividly seen in her 1925 piece Sadness (fig. 4). In this photomontage, a hybrid black and white figure occupies the center of the composition, which otherwise consists of an abstract background and a black border. Here, Höch assembles an intricate female figure that invokes some sort of deity and presents it to us on a pedestal, as if on display.

Höch’s photomontages owe greatly to her work with handicraft and textile design and her involvement in the commercial and publishing world of Ullstein, which constitutes part of the technical, material, and formal ecology of her artistic work. As a designer at Ullstein, Höch enjoyed easy access to a wealth of resources, including multiple copies of sewing and handiwork patterns produced by the company, as well as a vast array of illustrated magazines and other printed material. She incorporated these materials, along with recycled textile items, printed papers, and photographic reproductions sourced from various magazines—that she meticulously organized in scrapbooks—in her first attempts with collage and photomontage from as early as 1919. For instance, needle-lace patterns appear in her 1919 collage White Form while diagrams of filet, a kind of net (or grid) into which a design is darned, serve as a background in Tailor’s Flower (1920), as well as her 1921 piece, On a Tulle Net Ground (fig. 5). Many of the media sources that Höch uses in her photomontages come from Ullstein publications such as BIZ and Die Dame. This is especially evident in her use of BIZ material in her Dada pieces Cut with the Kitchen Knife Heads of State (1918-1920), or Dada Panorama (1919) (see fig. 1).

The interrelation between Höch’s textile designs and her photomontage work extends beyond their technical and material analogies, making her work explicitly different from that of her male colleagues. Referencing Kay Klein Kallos’s 1994 dissertation on the relationship between design and the avant-garde in the work of Hannah Höch, art historian Maria Makela draws attention to the formal affinity between “Höch’s diagrams for darned filet and needle lace” and “the compositional structure of her neatly formatted collages and photomontages, which are basically two-dimensional and usually arranged on a vertical-horizontal grid” (fig. 6).6 To this analysis, one can add other matters of artistic form that are associated with textile design, such as the dynamic interplay of positive and negative forms, as well as the intricate relationship between background and foreground that characterize her photomontages (fig. 7). Admittedly, Höch’s work is more “surface-oriented,” more “strongly patterned,” and more “rigorously structured” than that of her male Dada colleagues, who took a more a violent, destructive, and chaotic approach to their photomontages and whose assemblages exude a sense of agitation and anti-coherence.7 The profound importance of textiles for Höch surfaces prominently in My House-Sayings, a farewell piece she made in 1922, following her separation from Haussman and withdrawal from Dada. Inspired by the German tradition of guestbooks in which visitors could leave wishes and sayings upon departing from one’s house, this complex and multilayered photomontage combines in a constructivist grid, various Dada emblems and sayings by Dadaists and other like-minded writers, along with carefully selected clips of photographs—including her own—and several pieces of textile designs that Höch places at the center of the composition.

While at Ullstein, Höch made a design for the cover of one of its pattern publications. Her sketch depicts the figure of a little girl with a bow on her hair holding a relatively enormous pair of tailor scissors. The girl sits atop of a sphere, which the faded longitude and latitude pencil-lines suggest is not a ball of yarn, but the globe. Its surface is layered with patterns of clothing “which appear like continents waiting to be sewn together,” as Max Boersma explains, while “the word listed beside them—einreihen [to line up]—carries textile, orderly, and militaristic associations.”8 In his interpretation, the sketch “can suggest the gathering of fabric along a line during the process of stitching, as well as the act of getting in line or joining ranks.”9 However, juxtaposed with the Communist emblem of the hammer and sickle, her sketch evokes another layer of meaning. In a manner analogous to the aspirations of communist proletarian solidarity among peasants and workers seeking to change the world, Höch’s symbol is suggestive of a constructive unity between the spheres of art and crafts as a means of changing the world. For Höch’s part, it seems like there was no contradiction between these two worlds. Such reading, however, disturbs the carefully crafted anti-art, anti-establishment, and anti-aesthetic myth of the Dada revolt. “From the outset, Höch’s photomontage aesthetic was deeply rooted in design traditions, and it was perhaps this as much as anything that led many to discount her work,” insists Makela, even the Dadaists themselves.10 The distinct and multifaceted nature of her artistic output make Höch resistant to easy labels and categorizations, but it might be precisely this radical resistance that makes Hannah Höch even more quintessentially ‘Dada.’

Höch’s ‘cutting with the tailor scissors’ begets a re-evaluation of the historiographic ‘cuts’ historians perform within their own historical montages. In his seminal theory of the avant-garde, Peter Bürger defines the historical emergence of the avant-garde movements in the early twentieth century as a break in the history of art and a violent rupture with the Institution Art, or the framework within which an artwork is produced and received.11 The narrative of Dada’s dismantling of “the cult of art” and the tradition of newness associated with it, as provocative and alluring as it is, curtails our understanding of the complexity and variety of responses that artists gave to the rise of modern industrial capitalism and eschew the multifaceted and often ambivalent ways in which the avant-garde movements participated in ‘the modern life.’ Weaving a genealogy that links the development of photomontage medium to the domestic arts and clothing reform, to style and fashion, to popular magazines and mass-advertisement, and beyond, to women’s pastimes and feminist activism, Höch’s artistic work offers valuable and nuanced insights into these issues. “Preferring to accept the evidence of hand cutting over the creation of seamless illusion,” Höch and her tailor scissors invite a closer look into the stitches, the threads, and the critical scraps that are often cut out in our historical montages.12

____________________

Iris Giannakopoulou is a PhD candidate in the History and Theory of Architecture at Yale University where she studies the relationship between architecture and politics in the postwar period. Her dissertation examines how the censorious climate of the early Cold War years impacted the practice, discourse, and overall culture of architecture in the United States. Her previous academic work involves spatial histories of radicalism in modern architectural design and urban planning practices, as well as the historical avant-garde movements’ significance in shaping individual and collective political possibilities. She holds a Diploma of Architecture from the National Technical University of Athens, Greece (2014) where she is a licensed architect, and a Master of Science Degree in Architecture Design as a Fulbright Scholar from the MIT School of Architecture (2018).

____________________

1. William Rubin, Dada, Surrealism and their Heritage (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1968), 42.

2. Rubin, Dada, Surrealism and their Heritage, 42.

3. Maria Makela, “By Design: The early work of Hannah Höch in context,” in The Photomontages of Hannah Höch, ed. Peter Boswell, Maria Makela, Carolyn Lanchner (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 1996), 59. In her essay “A few words on photomontage,” Höch refers to the “first instances of this form, i.e. the cutting and rejoining of photos or parts of photos,” which, among others, may be found “in the fading, curious pictures representing this or that great-uncle as a military uniform with a pasted-on head. In those days the head of a person was simply glued onto a pre-printed musketeer.” Höch, “Několik poznámek o fotomontáži,” Stredisko 4, no. 1. (April 1934), unpaginated; translated by Jitka Salaguarda as “A Few Words on Photomontage” and reprinted in Maud Lavin, Cut with the Kitchen Knife: The Weimar Photomontages of Hannah Höch (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 219–20.

4. Raoul Hausmann, “Photomontage,” in Photography in the Modern Era: European Documents and Critical Writings, 1913–1940, ed. Christopher Phillips, trans. Joel Agee (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Aperture, 1989), 178.

5. Ullstein Verlag’s portfolio included mass-circulation periodicals such as the Berliner Morgenpost (Berlin Morning Post), BZ am Mittag (Berlin Newspaper at Noon), the weekly Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung (Berlin Illustrated Newspaper), the liberal newspaper Vossische Zeitung, and a number of smaller circulation magazines.

6. Makela, “By Design,” 62. Also see, Kay Klein Kallos, “A Woman’s Revolution: The Relationship between Design and the Avant-Garde in the Work of Hannah Höch 1912-1922,” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin, Madison, 1994).

7. Makela, 62.

8. Max Boersma, “Global Patterns: Hannah Höch, Interwar Abstraction, and the Weimar Inflation Crisis,” Grey Room, no 91 (Spring 2023): 18.

9. Boersma, “Global Patterns,” 18.

10. Makela, “By Design,” 62. John Heartfield and George Grosz are said to have opposed her inclusion in the First International Dada Fair of 1920 and succumbed only after Raoul Hausmann threatened to withdraw his own work from the exhibition. Furthermore, in their memoirs, Höch mentioned her only in passing or omitted reference altogether. See, Richard Hülsenbeck, Memoirs of a Dada Drummer (1969), ed. Hans J. Kleinschmidt, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991); George Grosz, George Grosz: An Autobiography, trans. Nora Hodges (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997).

11. Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde, trans. Michael Shaw (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984).

12. Peter Boswell, et al., The photomontages of Hannah Höch, 2.

Adornment: The Mary L. Cornille (GRS’87) 39th Annual Boston University Graduate Symposium in the History of Art & Architecture

by Isabella Dobson

Returning to the Museum of Fine Arts Boston for the first time since 2019, the Mary L. Cornille (GRS’87) Boston University Graduate Symposium in the History of Art and Architecture brought scholars together under the theme of “Adornment.” Spanning two days, the symposium featured keynote speaker Dr. Jill Burke and seven graduate student panelists, all of whom presented their recent work on embellishment and decoration in the visual realm to an audience of students, faculty, community members, and generous sponsor, Mary L. Cornille.

Ranging from Mesopotamian floral wreaths to Chinese collars, the graduate student panelists synthesized historical context with visual analysis and showed that adornment is not a benign act; instances of adornment speak to the gender, class, ethnicity, religion, and more of both wearers and makers. Due to its potential for assigning and expressing significance, the practice of adornment spans cultures, time periods, and surfaces. Books, buildings, bodies, clothing, cookware, and canvases are all surfaces enriched with adornment in every type of medium. Adornment is unlimited in its manifestations and multi-faceted in its meanings. Reminding the audience of its continued salience, Dr. Jill Burke commented on the role that adornment plays in our modern world where the decorated body is now more visible than ever in the appearances that people carefully construct online through social media.

Moderated by PhD student Kaylee Kelley, the first group of panelists spoke to what adornment meant to communities across space and time. To start the day, the first panelist Raquel Robbins (University of Toronto) put forth her findings on floral adornments found in mass graves and the Tomb of Queen Pu-Abi from third millennium BCE Mesopotamia in her talk “Pretty Little Things: Floral Adornments and their Implications of the Royal Cemetery of Ur.” Revising the meanings assigned to the floral adornments by the cemetery’s original excavator, C. Leonard Woolley, Robbins suggested that the metallic leaves and rosettes attached to combs, pins, and wreaths would have symbolized abundance and perpetual life to their wearers. The second panelist Cortney Berg (City University of New York) presented “Lucas Cranach the Elder and Judith: Powerful Portraits of Tyrannicidal Women in Reformation Germany,” during which she noted the seriality of half-length paintings by Cranach depicting Judith with the head of Holofernes. Berg proposed that these images are portraits of specific women who don the guise of Judith in order to not only show off their wealth and beauty, but also portray themselves as Protestant resistors to tyranny. To conclude the first panel, Angela Crenshaw (Bard Graduate Center) shared her research on painted and embroidered badges worn by nuns in her talk “Agency in Adornment: Escudos de Monjas in New Spain.” She explained how circular escudos, or shields, which adorned the front of a nun’s habit and often depicted the Virgin Mary or other biblical scenes, represented moments of choice and personal identity.

After a brief yet thought-provoking question and answer session with the panelists, Dr. Jill Burke (University of Edinburgh) capped off the first day of the Symposium by giving an exciting preview of her forthcoming book. In How to Be A Renaissance Woman: The Untold History of Beauty and Female Creativity (expected August 2023), she argues that the jewels, cosmetics, and clothing that women adorned themselves with in the Renaissance were not necessarily indicative of slavish conformity to beauty standards, but could also be tools of expression and empowerment. Burke’s ideas even prompted some audience members to thoughtfully reassess aloud the accessories they had donned for the Symposium.

The next day’s panel, moderated by PhD student Shannon Bewley, featured four graduate students whose talks considered bodily adornment and its connections to colonial projects, global trade, ethnic identity, and respectability politics. Starting the day with her talk “Coral and the Kingly Body: The Peabody’s Coral Apron and the Benin Kingdom,” panelist Morgan Snoap (Boston University) examined what it means for objects to be removed from their original contexts, especially those meant to be worn on the body. She concluded that the coral apron in the Peabody Museum’s collection loses the power and sanctity derived from adorning the king’s body when it languishes, unworn, in the collection at Harvard University. The following panelist Katy Rosenthal (Bryn Mawr College) recentered Chinese makers and Parsi wearers of the jhabla tunic in her talk “Figures in The Clouds: Necklines on Chinese Embroideries for the Parsi Community in 19th Century India,” arguing that the “cloud collars” embroidered on these tunics acted as everyday reminders of the actors involved in contemporary global trade. Rachel Sweeney (University of North Carolina Chapel Hill) was the third panelist to take the podium for her talk titled “Performing ‘Irishness’: The Tara Brooch, Celtic Revival Brooches, and Ethnic Nationalism.” Through her research on the Tara Brooch’s design and its reproductions during the 19th century English Celtic Revival period, Sweeney demonstrated how the English used the original and its copies to establish the ancient Tara Brooch as an item symbolizing a shared lineage between the two nations—and reinforcing English rule in the process. To wrap up day two, Sybil F. Joslyn (Boston University) gave the last talk “Fighting for Prestige: Nineteenth-Century Ceremonial Fire Dress and the Performance of Respectability,” in which she introduced a number of early nineteenth-century painted hats worn by firemen during ceremonial events. Sybil argued that firemen wore these hats, which sported fire company names such as “Hope,” “Good Intent,” and “Vigilant,” to elevate their prestige in a society that had characterized them as raucous, violent, and callous. Presentations concluded with another question and answer session for the day two presenters and were followed by a round of applause for all of the panelists.

Covering an array of embellished artworks and material objects, the breadth of research, thoughtful questions, and camaraderie of the Symposium were a wonderful way to mark the return to an in-person event. This engaging program of Art Historical scholarship would not have been possible without the coordinators, PhD students Hannah Jew and Rachel Kline, as well as all the graduate student volunteers, faculty liaison and department administrative assistance, and the generous support of Mary L. Cornille. If the scholarship of our brilliant panelists is any indication, the theme of adornment will continue to be critically studied as an important visual and material intervention in the field of Art and Architectural History.

____________________

Isabella Dobson is a PhD student in the History of Art & Architecture at Boston University interested in the ways that eroticism, desire, and sensuality operate in paintings and prints of the female body from the Early Modern period.

“Philip Guston Now”

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

May 1–September 11, 2022

by Ateret Sultan-Reisler

Philip Guston (1913–1980) responded to events witnessed in person and print through painting. Guston’s The Tormentors (1947–1948), an enigmatic rectangle of cadmium red and ink black overlaid with thin organic forms, requires further interpretation. The title hints at the artist’s explained reaction to seeing a Life Magazine article documenting the resurgence of Ku Klux Klan activity in 1946.1 Yet, this was not the first time Guston experienced the racist organization; a son of Jewish immigrants, the artist witnessed KKK marches growing up in Los Angeles. Curators and scholars generally analyze Guston’s oeuvre in the context of his personal anecdotes and broader art movements.2 However, his largest retrospective in two decades, MFA Boston’s Philip Guston Now grounds the artist’s personal experience and practice within a historical framework.3 Deciphering Guston’s reflections on harsh antisemitism and racism necessitates analysis of the chilling news reports he consumed. The retrospective tangibly brings a turbulent American political, racial, and militaristic climate to the fore: Philip Guston Now considers the artist’s work in dialogue with period news media and asks viewers to consider the artist’s work not only as personal meditation but as response to national and global oppression.

In a collapsed chronological order, the galleries show Guston’s early figuration, move to abstraction, and ultimate return to figuration. The first gallery spotlights Guston’s If this Be Not I, a demonstration of Guston’s earliest impulse to respond to worldwide issues. In the painting, masked and crowned children stage a performance on a street littered with newspaper and debris (fig. 1).4 The second gallery brings on the primarily sequential exhibition. In Guston’s early work, Madonna and Christ child embrace and nudes pose in celestial, Surrealist-inspired settings. The curators cite these paintings as aesthetically inspired by Max Ernst and Giorgio de Chirico.5 However, soon after, news of World War II brought forth issues demanding critical response. While teaching at Washington University, St. Louis in 1945, Guston first learned of the atrocities of World War II. Lest We Forget, a 1945 exhibition of Joseph Pulitzer Jr.’s photographs of liberated concentration camps, inspired Guston to depict the suffering he witnessed in a series of highly inscrutable paintings.6 Juxtaposing these works with visual testaments to the victims of Nazi violence urges viewers to consider how Guston’s work speaks to atrocities observed from afar.

Next, the exhibition features Guston’s brief period of abstraction followed by his racially charged work. Following Guston’s vivid action paintings conjuring the New York School, renderings of everyday domestic objects are scattered quirkily across a wall (fig. 2). However, Guston’s next body of work reacted to the unrest of the Civil Rights Era—a period in which Black activists brought racial oppression and white supremacy to the political forefront. Sparked by the tumult, Guston spoke to these issues through road-tripping, smoking, and bumbling Ku Klux Klan figures (fig. 3). Considering the sensitivity of this imagery, the more challenging paintings can be viewed in a semi-enclosed vestibule (fig. 4). Critiqued at the 1970 Marlborough Gallery show for their lack of skill, Guston’s efforts to address pervading white guilt and racial oppression were overlooked.7 At the MFA, klansmen painted in bright white and pink were paired with films of police violence against Vietnam War and Civil Rights activists.8 Framing his works with media footage encourages viewers to reflect and question the ways Guston’s works critically responded to racial and political turbulence of his era.

The final galleries frame Guston’s late paintings as responses to a buildup of memories and invite visitor response. Some of the gallery space is devoted to personal meditations in which Guston grappled with losing his wife, Musa. Another section features Guston’s work whilst a teacher at Boston University when protests for desegregation erupted on campus.9 The response station, a place for visitors to hang written responses on a wall with wooden pegs, underscores the heaviness of the content and urges visitors to forge meaningful connections between Guston’s work and period events. So easily could Guston have become numb to the constant ebb and flow of injustice in the news cycle. However, the exhibition’s grounding of shocking media pushes the argument that Guston fought against bigotry as a mundane feature of life. The exhibition urges viewers to reckon with how Guston’s method of bearing witness resonates with injustices broadcasted today.

____________________

Ateret Sultan-Reisler is the John Wilmerding Intern in American Art at National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. She is working on a major retrospective of Elizabeth Catlett (2024–25). Ateret holds an MA in History of Art & Architecture from Boston University and a BA in Art History and Psychology from University of Maryland.

____________________

Footnotes

1. As a winner of the Carnegie Institute prize for painting, Guston was featured in the back of a 1946 Life Magazine issue. It is possible that The Tormentors (1947–1948) was in reaction to the article: “Ku Klux Klan Tries a Comeback,” Life, May 27, 1946.

2. For the preceding Guston retrospective consult Michael Auping and Ashton Dore, Philip Guston Retrospective (Fort Worth: Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, 2003).

3. The MFA Boston curatorial team included Megan Bernard, Ethan W. Lasser, Kate Nesin, and Terence Washington.

4. In an earlier published version of this essay, the image The Porch (1945) was included instead of If This Be Not I (1945). It was amended for accuracy on May 14, 2023.

5. For further Guston scholarship, see the exhibition catalog, Harry Cooper, Mark Godfrey, Alison de Lima Greene, Kate Nesin, Philip Guston Now (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2020).

6. The photographs were taken from Joseph Pulitzer Jr.’s “A Report to the American People,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 1945. These visual testaments of victims to Nazi-orchestrated concentration camps can be viewed in the exhibition by lifting a fabric case covering. Guston explained that viewing imagery of the unspeakable horrors of the Holocaust led him to create highly obscured paintings.

7. Guston’s Klansmen continue to cause controversy today. The multi-venue exhibition was originally slated to open in 2020, but was postponed due to the pandemic and a reckoning with racial violence in the U.S. The curators at MFA Boston; National Gallery of Art, Washington DC; MFA Houston; and Tate Modern, London took time to bolster their interpretation framework for challenging subject matter and reconsidered the installation design for the Klansmen pictures to enhance viewer sensitivity.

8. Media footage includes that from the Democratic National Convention, August 26–29, 1968; Vietnam War, footage from late 1960s–early 1970s; Kent State shooting, May 4, 1970; Richard Nixon, U.S. President, 1960–1974. This footage was captured or is owned by Onyx Media, Nexstar WGN, Chicago, ABC News, NBC News, Hearst Newsreel, Christopher Jensen, ITN, and Encyclopedia Britannica Films.

9. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston exhibition text.

The Clown at Midnight: Coulrophobia, Counterculture, and the Decadent Pierrot Mask

by Samuel Love

Writing Pyrotechnic Insanitarium (1999), an apocalyptic account of twentieth-century Western culture, Mark Dery was sure of one thing: “all the world hates a clown.”1 In Dery’s eyes, the clown persistently haunted the waning century, resulting in the appearance of the term “coulrophobia”—an uncontrollable fear of clowns in popular discourse. The association between clowns and fear was so strong that Robert Bloch, author of 1959 cult classic Psycho, stated “the essence of true horror” was reified in “the clown, at midnight.”2 This fear, Dery argued, resulted from “the duplicity implied by the frozen grins and false gaiety of clowns…[Their] transparent artificiality constantly directs our attention to what’s behind the mask.”3 In other words, what provoked this visceral reaction was an uncanny failure of authenticity.

Dery could have observed the same phenomenon a century earlier. Beginning in the 1880s, the figure of Pierrot, the white-faced clown of the commedia dell’ arte, proliferated in the cultural imaginary of European modernism. This renewed interest paralleled the emergence of what would now be considered early coulrophobic reactions.4 Pierrot became a totem for the artists and writers who were, often self-consciously, considered to be “Decadents”—representatives of a French (or more generally, Western European) artistic movement characterized by its hedonism, pessimism, and provocative defiance of social and moral convention—precisely because of the destabilizing force of the clown’s artifice.

This allegiance between artist and clown has typically been viewed with suspicion in modernist scholarship. Benjamin Buchloh’s seminal 1981 polemic “Figures of Authority, Ciphers of Regression” evinced a form of conceptual coulrophobia in attacking specifically the utilization of commedia imagery as “enforced regression…the clown functions as a social archetype of the artist as an essentially powerless, docile, entertaining figure.”5 But in Decadent circles and those they influenced, Pierrot recurs for the opposite reasons. For example, the French graphic artist Jules Chéret (1836–1932) spoke for his generation in valorizing the Pierrot costume’s “mysteriousness…which disquiets the spectator with [its] expressionless white face….the hermetic curtain behind which one will try to see the man.”6 This essay explores how the uncanny inauthenticity of the Pierrot mask has been harnessed from nineteenth-century Decadents to their progenies in the “pyrotechnic insanitarium” of the twentieth, the aesthetes of glam rock who Dery acknowledged as the rightful heirs to Decadent art, to articulate a radical disidentification with contemporary social and moral conventions.7

The history of the Decadent Pierrot has been extensively elucidated in extant scholarship.8 Nascent in touring Italian pantomimes of the sixteenth century, the figure of a naïve Pierrot typically falls in love with the wholesome Columbine, who rejects him for the rougher, bolder Harlequin. Resultantly, Pierrot came to stand for a generalized sense of marginalization in Romantic circles in the nineteenth century. Pierrot emerged in the performances of Joseph Grimaldi (1778–1837) in London and Jean-Gaspard Deburau (1796–1846) in Paris, two actors whose tragic personal lives were popularly thought to underpin their interpretations of the suffering clown.9 The same circles appreciated the work of the French Rococo master Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721), whose isolated, mysterious Pierrot in Gilles dovetailed with their theatrical tastes (fig. 1). Although art historian Judy Sund has disproven that Watteau’s Pierrots were melancholy ciphers for the artist’s outsider status, this Romantic fiction perhaps took deep root because of pervasive associations between clowns and outsiders.10 Dery traces the origins of clowns to the disabled, impoverished, or otherwise non-normative performers of antiquity, establishing what he terms the “clown/freak connection” and the concretization of the clown as “abnormal or nonhuman Other.”11

The model of the clown inherited by late nineteenth-century Decadents was steeped in the language of suffering, rejection, and abnegation. It is precisely in this milieu that Pierrot’s alienation, rather than divested of meaning through repetition, as Buchloh suggests, was reinvigorated by the extent to which these attributes were embraced to épater la bourgeoisie. The association between the clown and marginal, transgressive identities inevitably led to the assumption that what was uncannily concealed by the inscrutable mask was a source of danger; as evidenced in Chéret’s enthusiasm for Pierrot, this was duly exploited by Decadent artists.

It was Chéret who provided illustrations for Pierrot Sceptique, a “pantomime” co-authored by the arch-Decadent J. K. Huysmans, in which Pierrot’s white blouse is symbolically replaced by black evening dress. Huysman’s Pierrot, no longer merely a sufferer, is a murderer and an arsonist in his own right.12 Chéret’s illustrations belie the interest in coulrophobia that Pierrot’s painted face could trigger. The discrepancy between the clown’s sadism and his fixed, atavistic, curiously apelike grin engenders this reaction (fig. 2). In canvases which have since largely disappeared into private collections, Chéret frequently depicted Pierrot as an airborne wraith menacingly toying with the chorus girls of the newly founded playhouse Moulin Rouge, its windmill a symbol of both the glamor and danger of fin-de-siecle Montmartre.

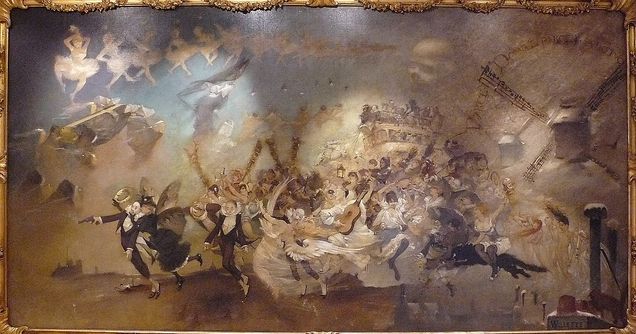

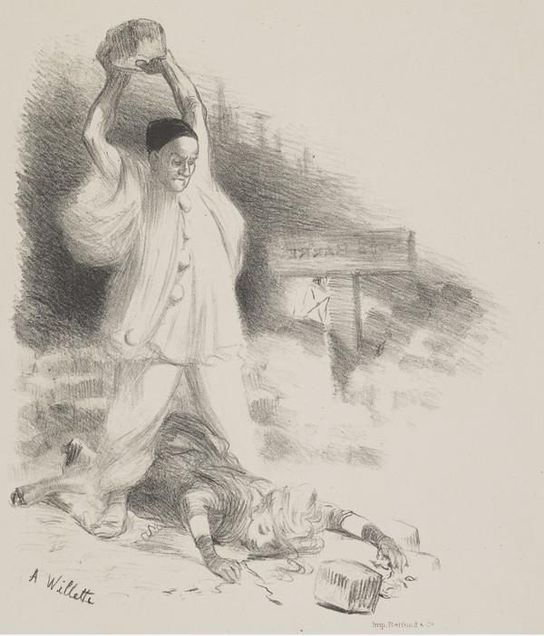

Indeed, the Moulin Rouge was itself designed by Adolphe Willette, who was known to sign his works as “Pierrot.” Willette also painted a mural for the nearby nightclub La Chat Noir that anticipates Mark Dery’s “pyrotechnic insanitarium” in its apocalyptic vision. Titled Parce Domine (fig. 3), a Pierrot attired in the same fashion as Chéret’s leads a bacchic procession of naked women, wolves, wraiths, and clowns down from the windmills of Montmartre and into a rapidly disintegrating landscape; the head of Willette’s procession brandishes a smoking pistol before him. Such atavistically violent Pierrots also permeate Willette’s minor works, evinced in drawings such as the brutish Pierrot the Murderer (fig. 4).

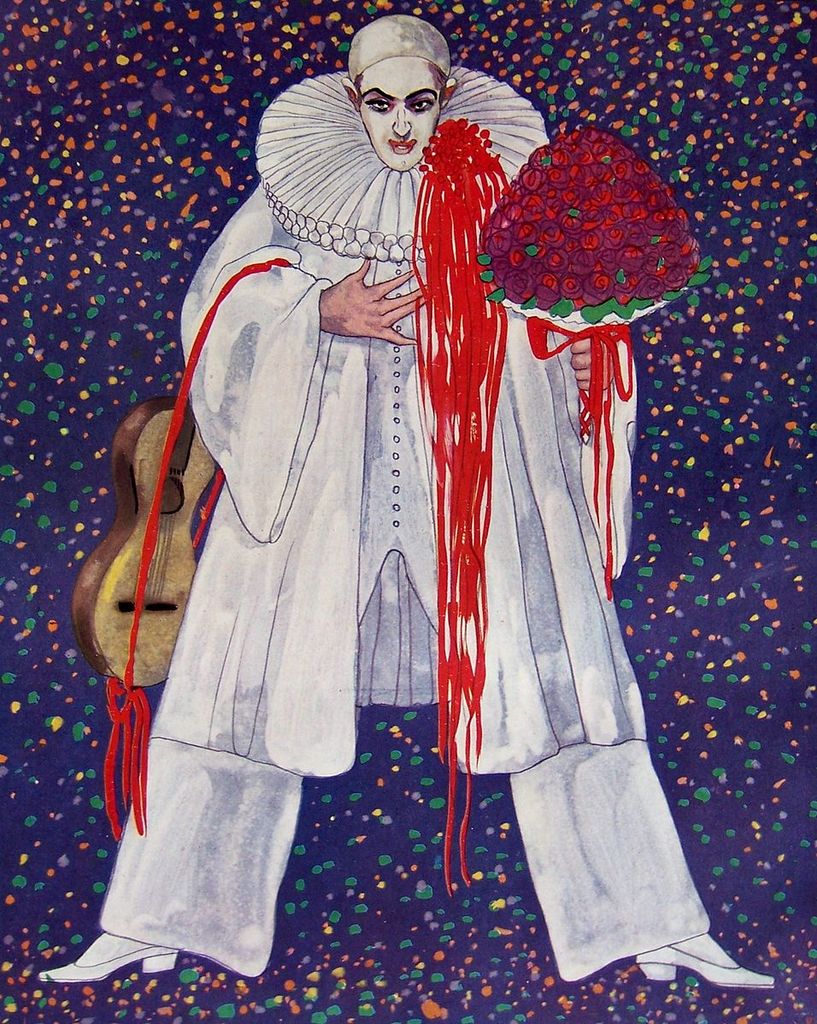

The theme of Pierrot as a threatening, violent force was reprised in the twentieth century by the likes of Gustav-Adolf Mossa and Leo Rauth. Mossa’s Pierrot of the Minute (fig. 5) (1908), indicating the influence of Huysmans and Chéret, features Pierrot brandishing a bloodied knife while clad in the immaculate garb of an eighteenth-century nobleman. Rauth’s subject of the monstrous and ironically named A Welcome Guest (1912), armed only with a bouquet of roses and a twisted grimace, seems to stream with blood from the illusionistic tumult of red ribbon clutched at his throat (fig. 6). Such creatures belong to the ranks of what journalist Benjamin Radford terms “bad clowns… vigilante antiheroes of the id”: inscrutable, inhuman beings whose painted faces at once conceal and suggest a sadistic moral void beneath.13

Yet, not all Pierrots became monsters; some simply embraced the artificiality of their pose, constituting the clown’s conceptual affront to authenticity as opposed to the visceral affront provided by his uncanny appearance. The decadent poet Arthur Symons understood Pierrot as “condemned to be always in public….he must remember to be fantastic if he would not be merely ridiculous….And so he becomes exquisitely false.”14 This is precisely the inauthenticity that enraged Buchloh in clownish iconographies, translated into psychological terms by Martin Green and John Swan who argue that “to feel oneself to be a commedia character gives one a sense of self that is hard to combine with…marriage and parenthood.”15 It is perhaps fitting that Arthur Symons was writing of his friend Aubrey Beardsley, who “was…this Pierrot” in Symons’s eyes, and whose tuberculosis meant that he would not live past twenty-five.16 Renowned for his exuberant dandyism, Beardsley was known to have quipped that “even my lungs are affected” in reference to his fatal ailment.17

It was, however, arguably not until the years immediately preceding the publication of Buchloh’s “Figures of Authority” that the pose practiced by Aubrey Beardsley was transformed into a method of transcending the boundaries of conventionality by Decadence’s most flamboyant progeny: glam rock. David Bowie, glam’s most intellectual acolyte, established a manifesto of sorts in stating that music should be “a parody of itself…[it should be] the clown, the Pierrot medium.”18 And in its theatrical inauthenticity it was, although its appropriation of Pierrot asked the opposite question to that of its Decadent forebears. If the likes of Willette associated Pierrot with criminality to attain distance from bourgeois conventionality, glam’s luminaries began from a position of near-criminality and found in the inauthenticity of the mask a provocative rebuke to encroaching bourgeois conventionality.

As Mark Fisher observed, glam “has a special affinity with the English suburbs,” where its luminaries grew up: “its ostentatious anti-conventionality was negatively inspired by [the suburbs’] eccentric conformism.”19 Critiquing its gender politics, Fisher also notes that glam was predominantly the “preserve of male desire,” which unwittingly elucidated the arena of glam’s “ostentatious anti-conventionality”: male sexuality, with homosexuality only decriminalized four years before glam’s explosion in 1971, and glam’s aesthetics embracing a provocative effeminacy and androgyny which flirted with a disruptive queerness.20 It was, again, Bowie who made this clear. Bowie had performed as Pierrot under the tutelage of the mime artist Lindsay Kemp, with whom he had a sexual relationship. Kemp had also promoted the work of Decadent writers to him, making the Pierrot character the first Bowie assumed before raiding the dressing-up box for others throughout the 1970s.21

When this journey of experimentation ended in 1980, it was Bowie in the spectacularly bejeweled Pierrot costume, captured by photographer Brian Duffy in the music video for Ashes to Ashes, who announced the effacing of the singer’s first publicly recognizable character from Space Oddity—“We know Major Tom’s a junky.” Yet, under the mask of Major Tom lay the mask of Pierrot: Bowie’s putting away of childish things did not result in the throwing on of bourgeois normativity. Instead, he remained the outsider incompatible with the values of heteronormative adulthood. Significantly, pop star Steve Strange, who appeared in the Ashes to Ashes video, reprised the role of Pierrot in the early 1980s, as did Klaus Nomi, a backing singer in a televised performance of Bowie’s The Man Who Sold the World.

Journalist Simon Reynolds records that glam “drew attention to itself as a fake” in its quest to “escape from reality into a never-ending fantasy of fame and freakitude.”22 In this, Bowie’s identification of the movement with commedia is obvious. The cultural logic of commedia that Green and Swan observe is echoed by glam’s demand to reject quotidian reality to preserve its dreamworld. Reynolds, however, does not entertain the possibility that many of those who sought this dreamworld had been forbidden entry to its alternative: the suburban world of their childhoods. Evinced in the sexual politics of glam is a rerun of Pierrot’s Decadent identification with the freak. Thus, the failure of authenticity that triggered nineteenth-century coulrophobic reactions to the white visage of Pierrot during the fin-de-siecle was translated into a twentieth-century conceptual failure of authenticity under glam: what unites the two artistic circles is how this failure was reconceptualized as a critical, countercultural strength.

____________________

Samuel Love is a PhD candidate in History of Art at the University of York. His thesis explores the carnivalesque visual culture of interwar British High Society, tracing how its engagements with baroque and Dionysian iconographies constituted a transgressive rejection of sociopolitical norms.

____________________

Footnotes

1. Mark Dery, Pyrotechnic Insanitarium: American Culture on the Brink (New York: Grove, 2000), 65.

2. See Benjamin Radford, Bad Clowns (New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, 2016), 21–22, for this quotation from Robert Bloch.

3. Dery, Pyrotechnic Insanitarium, 74.

4. This thesis is most comprehensively explored in: Martin Green and John Swan, The Triumph of Pierrot: The Commedia Dell'arte and the Modern Imagination (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993); Andrew McConnell Stott, “Clowns on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown: Dickens, Coulrophobia, and the Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi,” Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 12, no. 4 (2012): 4.

5. Benjamin Buchloh, “Figures of Authority, Ciphers of Regression: Notes on the Return of Representation in European Painting,” October 16 (1981): 53.

6. See Robert Storey, Pierrot: A Critical History of a Mask (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1978) 121, for this quotation by Jules Chéret.

7. For an extended exploration of the evolution of glam, see Mark Dery, All The Young Dudes: Why Glam Rock Matters, Boing Boing, 2013.

8. The authoritative study remains: Storey, Pierrot, 3–93.

9. Stott, “Clowns on the Verge,” 9–11.

10. Judy Sund, “Why so Sad? Watteau's Pierrots,” The Art Bulletin 98, no. 3 (2016): 321–323.

11. Dery, Pyrotechnic Insanitarium, 77, 79.

12. Dery, Pyrotechnic Insanitarium, 119.

13. Radford, Bad Clowns, 4.

14. Arthur Symons, The Art of Aubrey Beardsley (New York: The Modern Library, 1925), 28.

15. Green and Swan, Triumph of Pierrot, xvii.

16. Symons, Aubrey Beardsley, 28.

17. David Colvin, Aubrey Beardsley: A Slave to Beauty (New York: Welcome Rain, 1998), 53.

18. Quoted in Alexander Carpenter, “‘Give a Man a Mask and He’ll Tell the Truth’: Arnold Schoenberg, David Bowie, and the Mask of Pierrot,” Intersections: Canadian Journal of Music 30, no. 2 (2011): 7.

19. Mark Fisher, “For Your Unpleasure,” in Punk Is Dead: Modernity Killed Every Night (Winchester: Zero Books, 2017), 178.

20. Fisher, “For Your Unpleasure,” 178.

21. Simon Reynolds, Shock and Awe: Glam Rock and Its Legacy: From the Seventies to the Twenty-First Century (London: Faber and Faber, 2017), 88.

22. Reynolds, Shock and Awe, 3–5.

Performance and Imitation: Sofonisba Anguissola’s “Self Portrait with Madonna and Child”

by Emma Lazerson

Sofonisba Anguissola (1532?–1625) has been lauded as one of the most prolific portrait painters of the early modern period, but her devotional images have been largely understudied. This essay examines her Self-Portrait with Madonna and Child, a painting showcasing both Sofonisba’s style and that of other artists as a form of emulative adaptation: in her visible imitation, Sofonisba fashions herself as a courtier, while also alluding to her fitness for such a position through the embedded devotional image.

The Self-Portrait with Madonna and Child features Sofonisba gazing out at the audience, painting an image of the Madonna and Child, her brush coloring the flesh of Christ (fig. 1). The Madonna is youthful and idealized with her hand gently cupping the back of a nude Christ Child’s head, while the other delicately rests against his cheek, in preparation for a symbolic nuptial kiss. In painting the Madonna, Sofonisba inserts herself into Boccaccio’s history of illustrious women from his Concerning Famous Women (1374).1 In his text, Boccaccio refers to women from all different stations, but he specifically describes three famous classical artists, including Thamyris, painter of the goddess Diana. She was known for her chastity and was often conflated with the Madonna in the early modern period.2 It is likely that Sofonisba would have read Boccaccio’s text and may have identified with Thamyris.3 By painting the Madonna, Sofonisba places herself in dialogue with Thamyris, indicating her own longing for fame, her own desire for recognition as an artist.4 This desire was further exemplified by the fact that she sent such images to powerful courts throughout Europe, including that of Philip II of Spain, her future employer.5 Such images could have functioned as an informal sort of job interview, in which Sofonisba marketed her skills to appeal to the courts.

To aid her self-promotion, she turned to Baldassare Castiglione’s The Book of the Courtier (1528) for a description of how the ideal courtier could represent herself.6 Castiglione’s work features an open dialogue between various members of the Gonzaga Court in Urbino, but early modern readers viewed the text as prescriptive.7 It is this sort of reading that likely informed Sofonisba’s self-portrayal. In her self-presentation, she goes beyond an austere self-fashioning, directly fitting into one of the ways an ideal courtier could dress according to Castiglione. Sofonisba’s expression in her self-portrait is “grave and sober,” as she wears a plain black dress with a high neckline, which respectively aligns with Castiglione’s description of an ideal courtier as she paints with the most “pleasing” color and shows the “sobriety which the Spanish nation so much observes.”8 She signals key characteristics that Castiglione ascribed to the ideal courtier: modesty, reservedness, diligenza, and sprezzatura—an affected appearance of ease. Her clothes are demure and without frills, and her expression is undemonstrative, indicating her modesty and reservedness. Though her expression is impassive, Sofonisba shows her propensity for labor in her partially rotated pose, steady hold on the brush and maulstick, and tense arm muscles. All are signs emblematic of the diligenza she employs in her art and, presumably, in her life. By relying on the prescriptions of Castiglione in her self-fashioning, Sofonisba presents herself as a courtier before ever working at a court, and she demonstrates her ease of assimilation in this performance as a courtier. Furthermore, her art of painting, which Castiglione esteems as a positive characteristic for a courtier, appears to be done with ease, as shown through the two modes and two styles in which she paints fluidly. In her self-portrayal, Sofonisba paints in a manner established for her other self-portraits, while in the easel painting, she employs the manners of Correggio and Parmigianino. This oscillation is also representative of an affected appearance of ease, a point to which I will return. Her self-fashioning reflects the concerns of Castiglione’s court and her own desire to adapt to such a setting.

Sofonisba portrays herself according to Castiglione’s outline, and the embedded easel painting in the Self-Portrait may further show her ability to assimilate her style to that of other artists, a capability valued in a court painter, which Michael Cole contends Sofonisba aspired to be.9 Assimilation acted as the mechanism by which Sofonisba would be able to become a court artist, as the Spanish sought continuity in their portraits.10 The Madonna and Child is rendered in a style different from the one she uses to portray herself and akin to that of the painters Correggio and Parmigianino. In her early career, Sofonisba would have been exposed to the style of Correggio through her teacher Bernardino Campi, and she may have seen Parmigianino’s work through the large number of prints he disseminated throughout his career.11 Sofonisba’s Madonna resembles the Madonna of Correggio’s Virgin Adoring the Christ Child (fig. 2), borrowing Correggio’s soft portrayal of flesh, rosy cheeks, thick dark hair, and small softened lips. Sofonisba’s Christ Child also adopts Correggio’s blonde, fine curls visible in works such as Madonna and Child with an Angel (fig. 3). This is in contrast to the figures in her early non-devotional genre scenes, such as The Chess Game, in which her sisters are shown in a non-idealized fashion but with a naturalism characteristic of Lombard art.12 Sofonisba’s embedded canvas alludes to Correggio, but her image is not a one-to-one copy of Corregesque style.