The Clown at Midnight: Coulrophobia, Counterculture, and the Decadent Pierrot Mask

by Samuel Love

Writing Pyrotechnic Insanitarium (1999), an apocalyptic account of twentieth-century Western culture, Mark Dery was sure of one thing: “all the world hates a clown.”1 In Dery’s eyes, the clown persistently haunted the waning century, resulting in the appearance of the term “coulrophobia”—an uncontrollable fear of clowns in popular discourse. The association between clowns and fear was so strong that Robert Bloch, author of 1959 cult classic Psycho, stated “the essence of true horror” was reified in “the clown, at midnight.”2 This fear, Dery argued, resulted from “the duplicity implied by the frozen grins and false gaiety of clowns…[Their] transparent artificiality constantly directs our attention to what’s behind the mask.”3 In other words, what provoked this visceral reaction was an uncanny failure of authenticity.

Dery could have observed the same phenomenon a century earlier. Beginning in the 1880s, the figure of Pierrot, the white-faced clown of the commedia dell’ arte, proliferated in the cultural imaginary of European modernism. This renewed interest paralleled the emergence of what would now be considered early coulrophobic reactions.4 Pierrot became a totem for the artists and writers who were, often self-consciously, considered to be “Decadents”—representatives of a French (or more generally, Western European) artistic movement characterized by its hedonism, pessimism, and provocative defiance of social and moral convention—precisely because of the destabilizing force of the clown’s artifice.

This allegiance between artist and clown has typically been viewed with suspicion in modernist scholarship. Benjamin Buchloh’s seminal 1981 polemic “Figures of Authority, Ciphers of Regression” evinced a form of conceptual coulrophobia in attacking specifically the utilization of commedia imagery as “enforced regression…the clown functions as a social archetype of the artist as an essentially powerless, docile, entertaining figure.”5 But in Decadent circles and those they influenced, Pierrot recurs for the opposite reasons. For example, the French graphic artist Jules Chéret (1836–1932) spoke for his generation in valorizing the Pierrot costume’s “mysteriousness…which disquiets the spectator with [its] expressionless white face….the hermetic curtain behind which one will try to see the man.”6 This essay explores how the uncanny inauthenticity of the Pierrot mask has been harnessed from nineteenth-century Decadents to their progenies in the “pyrotechnic insanitarium” of the twentieth, the aesthetes of glam rock who Dery acknowledged as the rightful heirs to Decadent art, to articulate a radical disidentification with contemporary social and moral conventions.7

The history of the Decadent Pierrot has been extensively elucidated in extant scholarship.8 Nascent in touring Italian pantomimes of the sixteenth century, the figure of a naïve Pierrot typically falls in love with the wholesome Columbine, who rejects him for the rougher, bolder Harlequin. Resultantly, Pierrot came to stand for a generalized sense of marginalization in Romantic circles in the nineteenth century. Pierrot emerged in the performances of Joseph Grimaldi (1778–1837) in London and Jean-Gaspard Deburau (1796–1846) in Paris, two actors whose tragic personal lives were popularly thought to underpin their interpretations of the suffering clown.9 The same circles appreciated the work of the French Rococo master Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721), whose isolated, mysterious Pierrot in Gilles dovetailed with their theatrical tastes (fig. 1). Although art historian Judy Sund has disproven that Watteau’s Pierrots were melancholy ciphers for the artist’s outsider status, this Romantic fiction perhaps took deep root because of pervasive associations between clowns and outsiders.10 Dery traces the origins of clowns to the disabled, impoverished, or otherwise non-normative performers of antiquity, establishing what he terms the “clown/freak connection” and the concretization of the clown as “abnormal or nonhuman Other.”11

The model of the clown inherited by late nineteenth-century Decadents was steeped in the language of suffering, rejection, and abnegation. It is precisely in this milieu that Pierrot’s alienation, rather than divested of meaning through repetition, as Buchloh suggests, was reinvigorated by the extent to which these attributes were embraced to épater la bourgeoisie. The association between the clown and marginal, transgressive identities inevitably led to the assumption that what was uncannily concealed by the inscrutable mask was a source of danger; as evidenced in Chéret’s enthusiasm for Pierrot, this was duly exploited by Decadent artists.

It was Chéret who provided illustrations for Pierrot Sceptique, a “pantomime” co-authored by the arch-Decadent J. K. Huysmans, in which Pierrot’s white blouse is symbolically replaced by black evening dress. Huysman’s Pierrot, no longer merely a sufferer, is a murderer and an arsonist in his own right.12 Chéret’s illustrations belie the interest in coulrophobia that Pierrot’s painted face could trigger. The discrepancy between the clown’s sadism and his fixed, atavistic, curiously apelike grin engenders this reaction (fig. 2). In canvases which have since largely disappeared into private collections, Chéret frequently depicted Pierrot as an airborne wraith menacingly toying with the chorus girls of the newly founded playhouse Moulin Rouge, its windmill a symbol of both the glamor and danger of fin-de-siecle Montmartre.

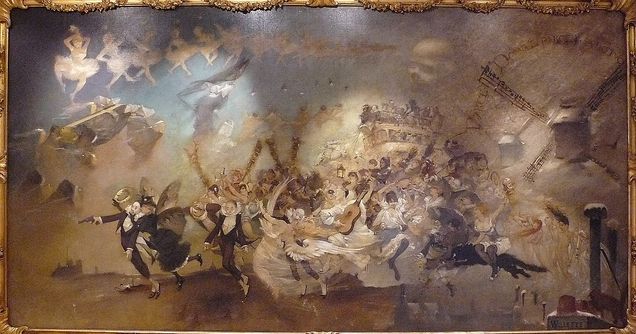

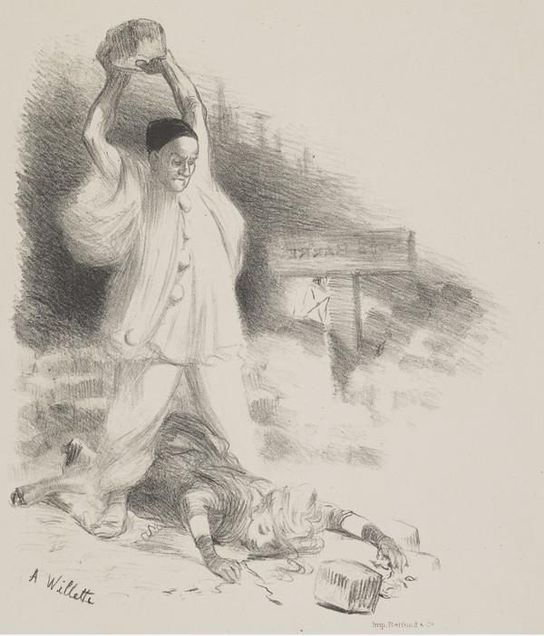

Indeed, the Moulin Rouge was itself designed by Adolphe Willette, who was known to sign his works as “Pierrot.” Willette also painted a mural for the nearby nightclub La Chat Noir that anticipates Mark Dery’s “pyrotechnic insanitarium” in its apocalyptic vision. Titled Parce Domine (fig. 3), a Pierrot attired in the same fashion as Chéret’s leads a bacchic procession of naked women, wolves, wraiths, and clowns down from the windmills of Montmartre and into a rapidly disintegrating landscape; the head of Willette’s procession brandishes a smoking pistol before him. Such atavistically violent Pierrots also permeate Willette’s minor works, evinced in drawings such as the brutish Pierrot the Murderer (fig. 4).

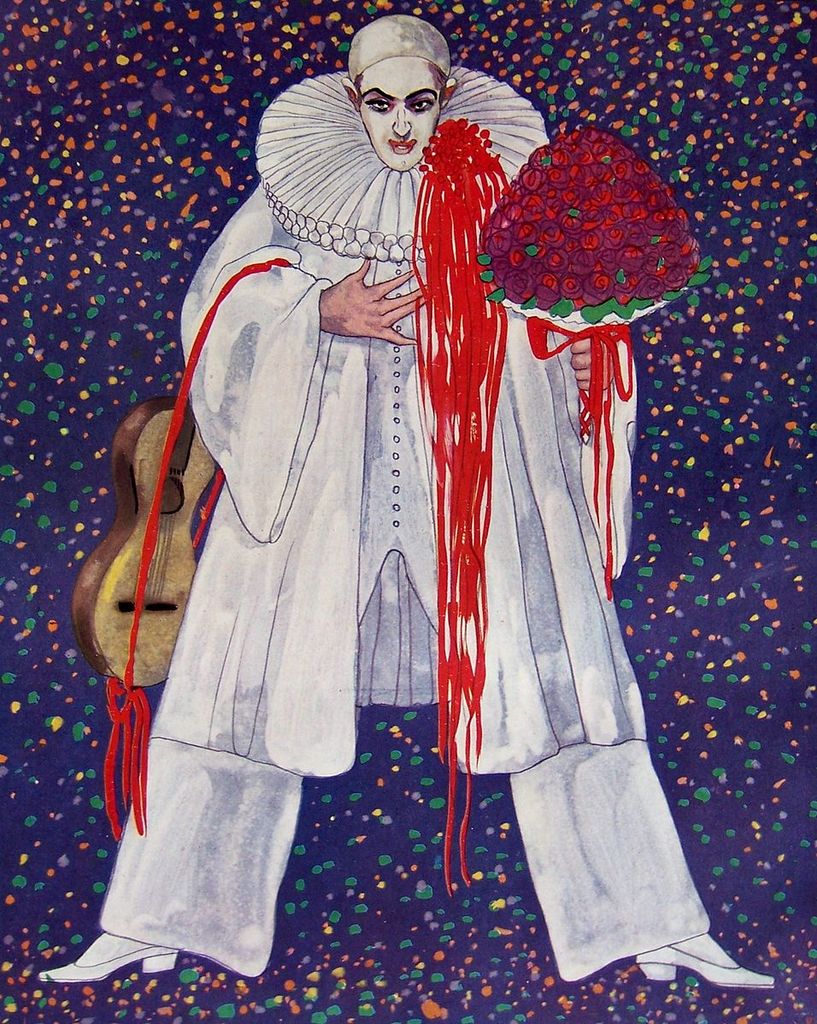

The theme of Pierrot as a threatening, violent force was reprised in the twentieth century by the likes of Gustav-Adolf Mossa and Leo Rauth. Mossa’s Pierrot of the Minute (fig. 5) (1908), indicating the influence of Huysmans and Chéret, features Pierrot brandishing a bloodied knife while clad in the immaculate garb of an eighteenth-century nobleman. Rauth’s subject of the monstrous and ironically named A Welcome Guest (1912), armed only with a bouquet of roses and a twisted grimace, seems to stream with blood from the illusionistic tumult of red ribbon clutched at his throat (fig. 6). Such creatures belong to the ranks of what journalist Benjamin Radford terms “bad clowns… vigilante antiheroes of the id”: inscrutable, inhuman beings whose painted faces at once conceal and suggest a sadistic moral void beneath.13

Yet, not all Pierrots became monsters; some simply embraced the artificiality of their pose, constituting the clown’s conceptual affront to authenticity as opposed to the visceral affront provided by his uncanny appearance. The decadent poet Arthur Symons understood Pierrot as “condemned to be always in public….he must remember to be fantastic if he would not be merely ridiculous….And so he becomes exquisitely false.”14 This is precisely the inauthenticity that enraged Buchloh in clownish iconographies, translated into psychological terms by Martin Green and John Swan who argue that “to feel oneself to be a commedia character gives one a sense of self that is hard to combine with…marriage and parenthood.”15 It is perhaps fitting that Arthur Symons was writing of his friend Aubrey Beardsley, who “was…this Pierrot” in Symons’s eyes, and whose tuberculosis meant that he would not live past twenty-five.16 Renowned for his exuberant dandyism, Beardsley was known to have quipped that “even my lungs are affected” in reference to his fatal ailment.17

It was, however, arguably not until the years immediately preceding the publication of Buchloh’s “Figures of Authority” that the pose practiced by Aubrey Beardsley was transformed into a method of transcending the boundaries of conventionality by Decadence’s most flamboyant progeny: glam rock. David Bowie, glam’s most intellectual acolyte, established a manifesto of sorts in stating that music should be “a parody of itself…[it should be] the clown, the Pierrot medium.”18 And in its theatrical inauthenticity it was, although its appropriation of Pierrot asked the opposite question to that of its Decadent forebears. If the likes of Willette associated Pierrot with criminality to attain distance from bourgeois conventionality, glam’s luminaries began from a position of near-criminality and found in the inauthenticity of the mask a provocative rebuke to encroaching bourgeois conventionality.

As Mark Fisher observed, glam “has a special affinity with the English suburbs,” where its luminaries grew up: “its ostentatious anti-conventionality was negatively inspired by [the suburbs’] eccentric conformism.”19 Critiquing its gender politics, Fisher also notes that glam was predominantly the “preserve of male desire,” which unwittingly elucidated the arena of glam’s “ostentatious anti-conventionality”: male sexuality, with homosexuality only decriminalized four years before glam’s explosion in 1971, and glam’s aesthetics embracing a provocative effeminacy and androgyny which flirted with a disruptive queerness.20 It was, again, Bowie who made this clear. Bowie had performed as Pierrot under the tutelage of the mime artist Lindsay Kemp, with whom he had a sexual relationship. Kemp had also promoted the work of Decadent writers to him, making the Pierrot character the first Bowie assumed before raiding the dressing-up box for others throughout the 1970s.21

When this journey of experimentation ended in 1980, it was Bowie in the spectacularly bejeweled Pierrot costume, captured by photographer Brian Duffy in the music video for Ashes to Ashes, who announced the effacing of the singer’s first publicly recognizable character from Space Oddity—“We know Major Tom’s a junky.” Yet, under the mask of Major Tom lay the mask of Pierrot: Bowie’s putting away of childish things did not result in the throwing on of bourgeois normativity. Instead, he remained the outsider incompatible with the values of heteronormative adulthood. Significantly, pop star Steve Strange, who appeared in the Ashes to Ashes video, reprised the role of Pierrot in the early 1980s, as did Klaus Nomi, a backing singer in a televised performance of Bowie’s The Man Who Sold the World.

Journalist Simon Reynolds records that glam “drew attention to itself as a fake” in its quest to “escape from reality into a never-ending fantasy of fame and freakitude.”22 In this, Bowie’s identification of the movement with commedia is obvious. The cultural logic of commedia that Green and Swan observe is echoed by glam’s demand to reject quotidian reality to preserve its dreamworld. Reynolds, however, does not entertain the possibility that many of those who sought this dreamworld had been forbidden entry to its alternative: the suburban world of their childhoods. Evinced in the sexual politics of glam is a rerun of Pierrot’s Decadent identification with the freak. Thus, the failure of authenticity that triggered nineteenth-century coulrophobic reactions to the white visage of Pierrot during the fin-de-siecle was translated into a twentieth-century conceptual failure of authenticity under glam: what unites the two artistic circles is how this failure was reconceptualized as a critical, countercultural strength.

____________________

Samuel Love is a PhD candidate in History of Art at the University of York. His thesis explores the carnivalesque visual culture of interwar British High Society, tracing how its engagements with baroque and Dionysian iconographies constituted a transgressive rejection of sociopolitical norms.

____________________

Footnotes

1. Mark Dery, Pyrotechnic Insanitarium: American Culture on the Brink (New York: Grove, 2000), 65.

2. See Benjamin Radford, Bad Clowns (New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, 2016), 21–22, for this quotation from Robert Bloch.

3. Dery, Pyrotechnic Insanitarium, 74.

4. This thesis is most comprehensively explored in: Martin Green and John Swan, The Triumph of Pierrot: The Commedia Dell’arte and the Modern Imagination (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993); Andrew McConnell Stott, “Clowns on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown: Dickens, Coulrophobia, and the Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi,” Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 12, no. 4 (2012): 4.

5. Benjamin Buchloh, “Figures of Authority, Ciphers of Regression: Notes on the Return of Representation in European Painting,” October 16 (1981): 53.

6. See Robert Storey, Pierrot: A Critical History of a Mask (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1978) 121, for this quotation by Jules Chéret.

7. For an extended exploration of the evolution of glam, see Mark Dery, All The Young Dudes: Why Glam Rock Matters, Boing Boing, 2013.

8. The authoritative study remains: Storey, Pierrot, 3–93.

9. Stott, “Clowns on the Verge,” 9–11.

10. Judy Sund, “Why so Sad? Watteau’s Pierrots,” The Art Bulletin 98, no. 3 (2016): 321–323.

11. Dery, Pyrotechnic Insanitarium, 77, 79.

12. Dery, Pyrotechnic Insanitarium, 119.

13. Radford, Bad Clowns, 4.

14. Arthur Symons, The Art of Aubrey Beardsley (New York: The Modern Library, 1925), 28.

15. Green and Swan, Triumph of Pierrot, xvii.

16. Symons, Aubrey Beardsley, 28.

17. David Colvin, Aubrey Beardsley: A Slave to Beauty (New York: Welcome Rain, 1998), 53.

18. Quoted in Alexander Carpenter, “‘Give a Man a Mask and He’ll Tell the Truth’: Arnold Schoenberg, David Bowie, and the Mask of Pierrot,” Intersections: Canadian Journal of Music 30, no. 2 (2011): 7.

19. Mark Fisher, “For Your Unpleasure,” in Punk Is Dead: Modernity Killed Every Night (Winchester: Zero Books, 2017), 178.

20. Fisher, “For Your Unpleasure,” 178.

21. Simon Reynolds, Shock and Awe: Glam Rock and Its Legacy: From the Seventies to the Twenty-First Century (London: Faber and Faber, 2017), 88.

22. Reynolds, Shock and Awe, 3–5.