news

From the Tomb to the Museum Plinth: Chinese Burial Objects on Display in the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art

by Elaigha Vilaysane

In his 2009 journal article entitled “Enlivening the Soul in Chinese Tombs,” Chinese art historian Wu Hung contends that most European and American museums do not display Chinese funerary objects in their ritual and architectural context.1 As a result, the decontextualized display of these artifacts limits an understanding of their original function.2 Museums in the West already subject Chinese objects to a binary of display, either within the pre-existing framework of Western art or classified as anthropological or ethnological objects.3 For Chinese burial objects, this binary becomes further exacerbated as their identity is defined as “art” or “artifact” when they are divorced from their original archaeological contexts.4

My Master’s dissertation in the History of Art and Archaeology of East Asia examines how Chinese burial objects are displayed in two Western universal survey museums’ galleries: the Charlotte C. Weber Gallery at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City (Met) and the T.T. Tsui Gallery at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (V&A). These universal survey museums are characterized by their globally diverse collections spanning a geographically broad range of art history.5 To my knowledge, no existing research compares these two galleries. I critique these galleries in their roles as cross-cultural communicators. The efficacy of the galleries is determined by whether the displayed Chinese burial objects’ purpose and function is clearly conveyed to visitors, and if these objects are contextualized within dynastic Chinese history and culture through the semiotics of the space—such as object descriptions and accompanying wall texts—as well as within the space itself, including the architecture and other visual informants impacting their display.

Religious and philosophical dynastic Chinese beliefs informed the practice of utilizing burial objects to activate the tomb into a spiritual space for the deceased’s soul as a “microcosmic representation of the universe.”6 These burial objects, known as mingqi are “[…] portable tomb furnishings, mainly objects and figurines, that are specifically designed and produced for the dead.”7 Mingqi are largely what both the Met and the V&A display in their respective Chinese “burial” galleries.

The interpretation of sacred objects, like mingqi, is notably impacted by how they are displayed within a museum. Art historian Gretchen T. Buggeln identifies a trifold dynamic of the display of sacred objects in museums as a relationship between the viewer, who is informed by both the museum's interior and exterior architecture, and the object’s innate characteristics.8 Buggeln expands upon the influence of the museum’s architecture on the visitor experience by quoting museologist Carol Duncan, “[Museums] contain numerous spaces that call for ritual behavior, ‘corridors scaled for processions, halls implying large, communal gatherings, and interior sanctuaries designed for awesome and potent effigies.’”9 In addition, there exists a subconscious museum etiquette requiring visitors to keep low volume levels and to slowly circumambulate the gallery, which both exemplify ritual-like behavior.10 The influence of spatiality on the museum visitor’s understanding of sacred objects through “spatial semiotics [that] reinforce the devotional context,”11 such as the glass case or plinths, emphasizes the sacredness of these objects by distancing the viewer through a physical barrier.12

In displaying sacred objects, curators are tasked with representing intangible religious beliefs. Religious studies scholar Chris Arthur has addressed the general skepticism of how much one can depend on the gallery to provide a comprehensive overview of specific religious beliefs and practices through the display of their respective religious objects. Yet he is hopeful that an object’s description, albeit short in nature, can provide the visitor with a starting point for understanding.13 Although the original sacred environment can never be fully recreated, the museum remains responsible for presenting their collection of sacred objects within an atmosphere of respect.14 This is important to consider in forming our understanding of Chinese burial objects on display and especially the museum’s efforts to communicate their original sacred significance to the deceased.

Given the nature of its collection, my dissertation concludes that because the Charlotte C. Weber Gallery at the Metropolitan Museum of Art mostly contains ceramic mingqi from the Han and Tang Dynasties, the gallery is curated into a linear, chronological mode of display identifying and highlighting the progression of mingqi as burial art. Alternatively, the diversity of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s collection (spanning from the Neolithic era to the Ming Dynasty) allows its “burial” section of the T.T. Tsui Gallery to communicate with five other thematic sections of the gallery: Temple and Worship, Living, Eating and Drinking, Ruling, and Collecting. Thus, the T.T. Tsui Gallery presents mingqi as artifacts. By cohesively contextualizing the function of Chinese funerary objects in Chinese life and culture, the curation of the T.T. Tsui Gallery encourages the viewer’s visualization of the spiritual space, hence a more effective method for visitors to learn about the importance and function of Chinese funerary objects.

____________________

Elaigha Vilaysane received her BA in Chinese Language and Literature and Art History from the George Washington University in May 2023. She has recently completed her master’s degree at SOAS, University of London in History of Art and Archaeology of East Asia with a concentration in Chinese studies.

____________________

1. Wu Hung, “Enlivening the Soul in Chinese Tombs,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no 55/56 (Spring – Autumn, 2009): 41, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25608834.

2. Wu, “Enlivening the Soul in Chinese Tombs,” 41.

3. Steven Conn, “Where is the East? Asian Objects in American Museums, from Nathan Dunn to Charles Freer,” Winterthur Portfolio 35, no 2/3 (Summer – Autumn, 2000): 157-58, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1215363.

4. Ronald L. Grimes, “Sacred objects in museum spaces,” Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses 21, no. 4 (1992): 422-23.

5. Carol Duncan and Alan Wallach, “Chapter 3: The Universal Survey Museum,” in Museum Studies: An anthology of contexts, ed. Bettina Messias Carbonell (Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004), 54.

6. Wu, “Enlivening the Soul in Chinese Tombs,” 22.

7. Wu Hung, “Materiality,” In The Art of the Yellow Springs (University of Chicago Press, 2010), 87.

8. Gretchen T. Buggeln, “Museum space and the experience of the sacred,” Material Religion 8, no. 1 (2012): 45, https://doi.org/10.2752/175183412X13286288797854.

9. Buggeln, “Museum space and the experience of the sacred,” 37.

10. Buggeln, “Museum space and the experience of the sacred,” 37.

11. Louise Tythacott, “Curating the Sacred: Exhibiting Buddhism at the World Museum Liverpool,” Buddhist Studies Review 34, no. 1 (2017): 116, http://www.doi.10.1558/bsrv.29020.

12. Tythacott, “Curating the Sacred: Exhibiting Buddhism at the World Museum Liverpool,” 123.

13. Chris Arthur, “Exhibiting the Sacred,” in Godly Things: Museums, Objects, and Religion, ed. Crispin Paine (Leicester University Press, 2000), 5-6.

14. Tythacott, "Curating the Sacred: Exhibiting Buddhism at the World Museum Liverpool," 130.

Jijnasa (desire to know)

by Sayak Mitra

The crisscrossing threads of my identity as both a Bengali Indian and a conditional resident of the USA unfurl and entangle conventional forms of artistic knowledge. Through my paintings and installations, I assemble fragments of my life—past and present, seen and unseen—to describe the breadth of my multicultural experiences and the worlds in which I live.

I am interested in the Vedantic Nyãya-derived concept of DṚG DṚŚYA VIVEKA (the Seer and the Seen), which emphasizes philosophic inquiry and temporal unearthliness. Growing up in the suburbs of Calcutta and spending time in our rural desher bari (native country home) surrounded by mustard, potato, and jute fields, my earliest memories as a practicing artist involve building pandals (temporary ritual structures) and participating in household puja (sacred ceremonies of worship).

I live with a keen awareness of the origins and implications of materials. In my approach to the concept of dematerialization in art, I propose to expand the concept of auto-ethnographic embodiment by exploring the history of my materials, cultural interpretation, and subjective association, instead of rejecting the materiality of objects. To shape the visual reading of my material, I borrow tools from deconstructionism and semiotics that allow me to persuade dematerialization beyond its materiality and objecthood.

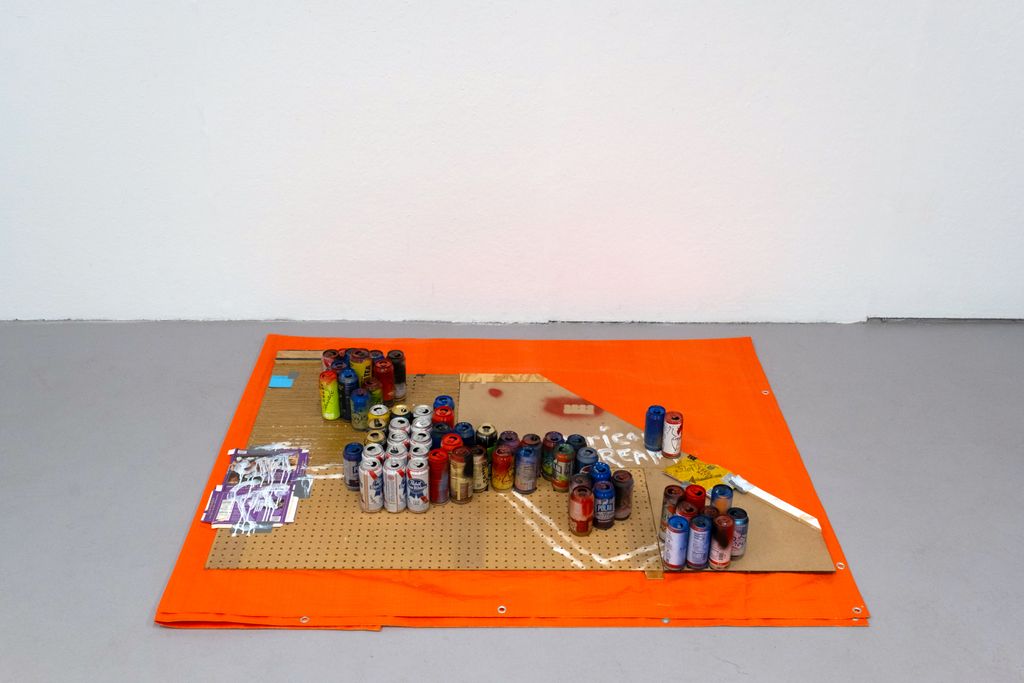

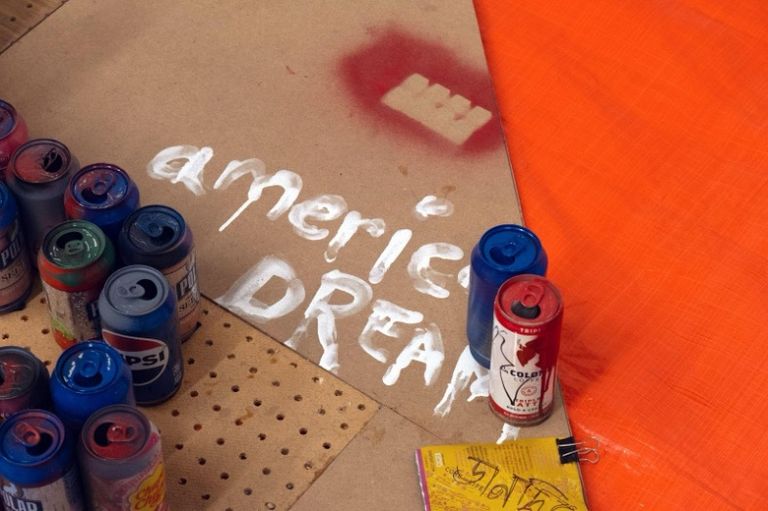

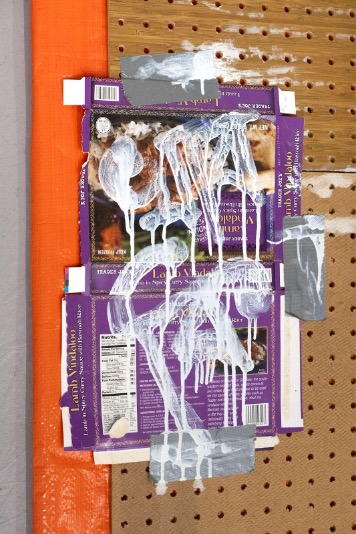

Figures 1-3. Sayak Mitra. Dhulagargh Industrial Park (2024). Acrylic, graphite, duct tape, food package, recyclable aluminum and steel cans, pegboard, wood, and tarp. Approximately 67 x 45 x 8 in. (170.2 x 114.3 x 20.3 cm). Images courtesy of the artist.

Examples of this approach are Dhulagargh Industrial Park (figs. 1-3) and Shakshi Chhilo Siddharth. Two primary materials, tarp and burlap, are used respectively for these two works. In Dhulagargh Industrial Park, mediums operate as mental images evoked by heterogeneous recyclable cans, upcycled fabrics, reclaimed materials, pigments, found objects, store-bought items such as home-improvement tools, urban development signs, etc. In West Bengal, the tarp has many purposes, including being used to dry parboiled rice and jackfruit seeds. I replaced seeds and rice with recycled cans, food packages, and makeshift signs. Parboiled rice is partially boiled and dried before milling and polishing, giving it a life before it is cooked for consumption. Similarly, after consuming green jackfruit, villagers collect, clean, and dry the jackfruit seeds for trade in the marketplace. Energy drinks, soda, beer cans, and frozen packed foods represent the working class in our society. The form of the cans echoes the stacks of kerosene barrels that are hauled around Calcutta on makeshift wagons (fig. 4).

In Dhulagargh Industrial Park, I play with the idea of the planogram and jnana yoga to design a coded metaphor for a global market. Jnana yoga is a disciplined practice of knowledge: it allows us to observe any phenomena beyond its literal significance. On the other hand, a planogram is a diagrammatic system that helps retail stores maximize their sales and feed the supply-demand requirements of capitalism. I used wood, pegboard on orange tarp, and a section of shelf to represent the myth of a grandiose global market (fig. 2). Merchandise tags from manufacturers that claim “fair-labor-standard-certified” reassure customers, while factory workers endure inhumane treatment to meet consumer demands. Products imported from overseas obscure the workers’ conditions, creating a system that shields customers from moral accountability and enables over-shopping. The shape of pegboards is an extractive, semi-fictional, cartographic representation of Dhulagarh Industrial Park in the Howrah district of West Bengal.

During the rise of the gig economy of the early 1970s, small-scale factories were established in newly built industrial complexes. During this time, employers were not responsible for providing basic labor support and exploitative companies were not held accountable. The irony of the post-colonial myth of India’s progress, juxtaposed with the extractive economy it inherited, has been glorified under the shadow of the “American Dream.” The phrase “American Dream” appears in parallel with the Indian protest slogan “Khabo Ki?” (“What can we eat?”) on a Trader Joe’s frozen Lamb Vindaloo package, reflecting the culinary culture of diasporic Indians (figs. 2-3). As it has become synonymous with remittances to Central and South Asia, the vindaloo dish evokes the bittersweet colonial legacy of Portuguese rule.

Figures 5-7. Sayak Mitra. Shakshi Chhilo Siddharth (2023). Graphite, acrylic, egg tempera, cardboard, aluminum signs, recyclable food packages, found woods, used gloves, burlap roll, stretched canvas, and reclaimed materials. Approximately 65 x 96 x 8 in. (165.1 x 243.8 x 20.3 cm). Images courtesy of the artist.

Shakshi Chhilo Siddharth showcases the socio-economic tension and societal hierarchy that operate as an aesthetic dialogue between several parameters: i.e. the customer of the local grocery, ambitious émigrés and refugees, collapse and vitality, disorder and systemization (figs. 5-7). This work was made in response to the architecture of the third floor of 808 Commonwealth Ave., a car factory turned into private art school studios in Boston. The main structure is made from a found divider wall and transformed into four wooden shelves leaning on the wall as we often see in diasporic grocery stores. The items on the shelf are carefully selected store-bought goods, drawings, and paintings. I propose a conversation between the plasticity of our “globalized idea,” and the stipulation of accessibility for many civilians who were not born in the affluent West or who have not benefited from the colonial extractive economy: between “JUST DO IT” and “DO NOT ENTER” (fig. 6). Half of the shelf is covered by burlap: in West Bengal, burlap is often repurposed into doormats, cushions, and curtains, giving discarded potato sacks a new life. This practice of deliberate repurposing reinforces cultural identity and underscores the metabolism of materials.

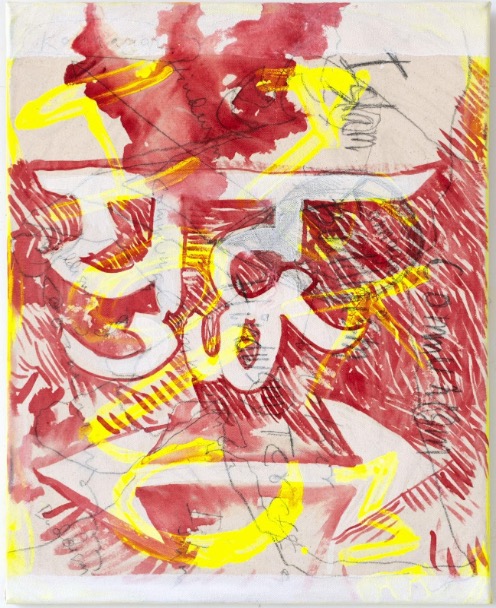

My practice ultimately aims to demonstrate how multiculturalism is an illusory neo-liberal concept that represents sovereignty rather than collective liberation. I’m interested in thinking about how the contemporary industrial complex bears and bares histories of colonial factories, and how my practice links ideas of empirical evidence with the myth of globalization. I see the world as a fragmented ensemble, and that fragmentation is excruciating. I seek to establish continuity through my research, paintings, and installations (figs. 8-14).

Figures 8-14. Sayak Mitra. Mindful Objective Investigation of Rationalist Narrative in the Gig Economy (2024); A Window At Industrial Park (2024); Ganashatru (2023); Untitled (2023); Untitled (2023); The flow of the Ganges (left panel of the triptych) (2023); International Mother Language Day (2022). Multimedia. Variable dimensions. Images courtesy of the artist.

____________________

Sayak Mitra (b. 1984, West Bengal) is an Indian artist working across traditional and contemporary new media art. His work addresses power, displacement, social injustice, and class issues through paintings, photographs, and installations. He graduated with a B.Tech from WBUT (2008) and an MFA in Painting from Boston University (2024). Sayak co-founded Artist-collective Ocular in 2006 and has exhibited globally, winning awards like the Hugh and Marjorie Petersen Award for Public Art and the Atul Bose Award for Painting.

____________________

editor’s introduction

by Catherine Lennartz

What lies beyond the veil? Some version of this question has inspired people from every walk of life to use mortality as a source of inspiration. No matter our beliefs, death and its unknowns have yielded varied forms of artistic production that remain evocative to this day. Rituals surrounding death permeate human history and make up a large part of the earliest examples of human creative production that we study as art and architectural historians. From funerary complexes to sacred objects and texts, from intuition and dreams to meditation and self-discovery, there is no doubt that imagining what exists beyond our lives has been a fruitful endeavor. Just south of Stockholm, Sweden, a cemetery called Skogskyrkogården marries architecture and landscape in its modern take on these age-old questions (fig.1).

The Woodland Cemetery, as it is known in English, utilizes landscape and nature to create a transitional space for people to come to terms with the new world they find themselves in after losing a loved one. It was built in the first half of the twentieth century following the designs of Erik Gunnar Asplund and Sigurd Lewerentz.1 Their partnership—though not without disagreements—resulted in a design that Caroline Constant describes as “imparting a sense of serenity in the face of death through reconciliation with nature.”2 The atmosphere is set by the entrance: a walled, semi-circular space that leads visitors into a long, narrow walkway. The retaining wall, standing around twelve feet tall, is topped by trees, evoking the sense of being below ground. As one walks down the road, the walls shrink, or rather the path rises, until an open grassy area is revealed (figs. 2-3). Coming into view to the left are the main chapels and crematorium serving the cemetery. Other chapels are spread across the grounds, offering a variety of options for memorial services of all kinds, religious or secular. The rest of the cemetery is covered with tall pine trees, creating a sheltered canopy over the gravestones occasionally crisscrossed by open avenues. No buildings stand taller than the trees across the grounds.

The largest chapel, the Chapel of the Holy Cross, echoes the entrance path’s transition from contained to open in the way it holds funerary services (fig. 4). Guests enter the chapel from an interior side door and sit facing a large curved and frescoed wall depicting scenes of Viking funerary practices. The floor angles down gently towards the altar where the coffin is laid. At the end of the service, guests are invited to walk up the sloping floor to the back of the chapel, where curtains are drawn, flooding the chapel with light and revealing a glazed wall protected by a wrought-iron grill. Both the window and the grill are then lowered into the ground, opening the whole wall onto a covered porch. At the center of this porch, in an opening reminiscent of a Roman compluvium, sits the Resurrection Monument, a bronze sculpture reaching for the sky. The porch sits at ground level, granting access to the lawn, paths, and lily-pond beyond. The whole funeral service thus transitions from a protected interior space for the duration of the ceremony and eulogies to a procession up and gradually out into nature. Each space offers the opportunity for pause, as the mourner wishes.

Figure 4. Virtual visit of Heliga korsets kapell (Chapel of the Holy Spirit) (2015). Photos Tommy Hvitfeldt.

Skogskyrkogården presents innumerable in-between places for reflection without ever claiming to offer explanations or answers. The cycles of dark and light, closed and open, that visitors experience during their time at the cemetery mirror the process of grieving, with darker and brighter moments sometimes emerging unexpectedly. The result is a space dedicated to the dead that cares deeply about what it can provide for the living.

In this issue, we have gathered scholarship that engages with artists, patrons, and institutions that question what lies beyond human perception: be it divinity, (im)mortality, or the supernatural. Our three feature essays investigate artistic practices that pose fundamental questions about our beliefs surrounding death and those who have passed. Drawing on the intersections of religious and artistic patronage, murder, architecture, and musical compositions, William Chaudoin describes the complex ways in which a sixteenth century nobleman, Carlo Gesualdo, sought to secure salvation for his soul. Centered around the commission of an altarpiece, this analysis showcases a belief in artistic devotion that could secure forgiveness in the afterlife for sins committed on earth. In an essay that turns its attention to the moments following death, Gillian Yee looks to the intimate photographs David Wojnarowicz took of Peter Hujar—his mentor and lover—moments after his death from AIDS-related complications. Here we are invited to reconsider our relationship with death and the passivity of the dead body through photographs that each show only a small part of Hujar. Each image holds meaning and identity, rejecting the binary of life and death to suggest alternative ways of being. Hamin Kim explores the myriad ways artists in Korea engage with fortune, fate, and chance through new practices echoing older forms of Shamanism. Through a series of examples, we begin to understand the dialogue between Korean traditions and Western modernity that underpin many of the resurging practices; the results allow for a more fluid understanding of humanity.

Sayak Mitra’s creative practice navigates the space between being a Bengali Indian and a conditional resident of the United States. In his paintings and installations, we are confronted by the illusory nature of the promises of neo-liberalism through materials that speak to both life in West Bengal and in Boston. Cultural identity is thus constructed through the material output of extractive economies and global corporations.

In our research spotlight, Elaigha Vilaysane emphasizes the importance of spatiality and context in the display of ancient Chinese funerary objects. Looking at two case studies from Western universal survey museums, Vilasayne’s dissertation research draws on a wide range of scholarship to analyze the impact of object labels, surrounding artworks, modes of display, gallery layout, and expected visitor behaviors in effectively conveying the religious and cultural functions of these objects.

This issue would have been incomplete without a review of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston’s exhibition dedicated to the work of Salvador Dalí. This exhibition proposes to connect Dalí’s work to that of many of his predecessors, often inviting a recognition of surrealist themes in earlier works. Kendall Murphy recognizes the value of expanding the idea of surrealism as a state of mind shared by artists beyond the traditional limits of the movement, but she warns against an oversimplification of Dalí’s turn towards Catholicism and conservatism later in life—a surprising lacuna considering the exhibition’s themes of disruption and devotion.

Though what lies beyond the veil might remain obscured, our authors have shown that this is not an obstacle to scholarship; rather, it reveals aspects of human nature through the ways we interact with each other and the world in the face of unanswered questions. This is a small reminder that we are always surrounded by other worlds: we can glimpse them when we open ourselves up to the points of view of the individuals, collaborators, colleagues, and communities that surround us.

____________________

Catherine Lennartz is a PhD student in the History of Art and Architecture at Boston University. Her research explores the intersection of exhibitions and memorials, memory-focused art, and remembrance, especially as they relate to human rights.

____________________

1. Kieran Long, Johan Örn, and Mikael Andersson, Sigurd Lewerentz: Architect of Death and Life, trans. Anna Paterson (Park Books, 2021), 26.

2. Caroline Constant, The Woodland Cemetery: Toward a Spiritual Landscape (Byggförlaget, 1994), 49.

Il Perdono di Gesualdo: Art, Sin, and Salvation

by William Chaudoin

Carlo Gesualdo, Conte da Venosa (c. 1566-1614)—composer, murderer, and patron of the arts—commissioned the Florentine painter Giovanni Balducci to create the altarpiece, Il Perdono di Gesualdo (fig. 1), in an attempt to alter his own fate. Gesualdo’s plan of intricate, multidimensional patronage is central to his desire to exercise control over what became of his soul. Employing music, painting, and architecture, Gesualdo sought to enhance his relationship with his uncle, Saint Carlo Borromeo.

Featured prominently in the altarpiece, Borromeo’s views on sacred art and music shaped Gesualdo’s patronage initiatives, especially in the latter half of Gesualdo’s life when he fell ill. Through strategic artistic choices, Gesualdo manifests a profound plea for redemption deeply connected to Borromeo, evidenced by his collection of Borromean relics, church-building efforts in the town of Gesualdo, and the inclusion of his uncle in the altarpiece's narrative. Therefore, we can view Gesualdo's efforts as an attempt to assert dominion over his fate wherein he grapples with a profound question: can one buy their way into salvation through acts of artistic devotion?

In seeking redemption, Gesualdo confronted the specter of his past sins: an overwhelming fear of what awaited him in the afterlife motivated and complicated his artistic and spiritual pursuits. Scholars Cecil Gray, Catherine Deutsch, and Glenn Watkins have debated Gesualdo’s motivations surrounding the altarpiece, while examining the contribution of his patronage and musical compositions to his social status.1 Carlo Gesualdo was a Neapolitan aristocrat with ancestral ties to the town of Gesualdo, where his family had been in power since the tenth century.2 He is infamous for the murder of his first wife, Maria d’Avalos, and her lover, Fabrizio Carafa, in 1590—an event that would plague his conscience. Reports of the murders emphasize Gesualdo’s frenzied actions, while other apocryphal accounts detail extreme gore and brutality.3 Four years later, Gesualdo married Eleonora d’Este, which exposed him to the innovative music of the Ferrara court, a city that had long been a hub of progressive musical activity.4 Here, Gesualdo published his first two books of madrigals in 1594, which showcased complex chromatic harmonies reflective of his inner turmoil.5 This transition, however, did not absolve his guilt; the weight of his past sins fueled his later acts of patronage, including the construction of two churches in Gesualdo—Santissimo Rosario (fig. 2) and Santa Maria delle Grazie (fig. 3)—the commissioning of Il Perdono di Gesualdo, and an accompanying collection of sacred music.

Early religious and familial connections informed Gesualdo’s patronage initiatives during the latter part of his life as he grappled with his impending mortality and fears of eternal torment. Born in 1566, Gesualdo was influenced by the Counter-Reformation initiated by the Council of Trent, which shaped the practices of sacred imagery and veneration.6 Carlo Borromeo, his uncle and a central figure in this movement, guided Gesualdo’s ecclesiastical aspirations. Gesualdo’s subsequent artistic patronage manifested as an attempt to exert control over his destiny, driven by both his guilt over the murder of his wife and his growing religious zeal. As his health deteriorated and his mortality became increasingly imminent, he turned to religion not only to confront his past actions but also to amend his legacy. His patronage served as a means to realign his fate with the protective power of his uncle, Carlo Borromeo, whether earthly, heavenly, or imagined; the altarpiece Il Perdono di Gesualdo at Santa Maria delle Grazie would symbolize his effort to extend that influence over the fate of his soul.

This effort to secure his salvation is embodied in the altarpiece Il Perdono di Gesualdo, which was commissioned by the prince himself and painted by Giovanni Balducci. Installed in the Santa Maria delle Grazie church in Gesualdo, this work serves as a focal point for both his personal devotion and his legacy. Il Perdono di Gesualdo is structured into three distinct realms: a celestial realm featuring divine figures such as Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, the Archangel Michael, Saint Francis of Assisi, Saint Dominic, Mary Magdalene, and Saint Catherine of Siena; an earthly realm that includes representations of Saint Carlo Borromeo, Carlo Gesualdo, and Eleonora d’Este; and a fiery realm depicting winged figures rising above the waiting souls.7 While representations of hell were not uncommon in Post-Tridentine art, the choice to place the figures in purgatory reflects the era’s growing emphasis on intercession and the belief in the transformative power of divine mercy.

In the altarpiece, Borromeo stands beside Gesualdo, his hand firmly resting on Gesualdo’s shoulder. Gesualdo, on bent knee and with clasped hands, gazes upwards toward the heavenly realm with a penitent expression, while Borromeo gestures toward him, interceding on his behalf (fig. 4). The shared focus of both figures, their eyes directed toward Christ, suggests a united plea for Gesualdo’s acceptance into Heaven, which frames the work as a manifestation of Gesualdo’s desire for redemption amidst the weight of his past sins, namely murder and adultery. The juxtaposition of Gesualdo’s penitent stance and Borromeo’s protective gesture visually contrasts the human act of seeking redemption with the divine intercession that promises salvation. This pairing invites reflection on whether salvation can be achieved through artistic devotion—symbolized by Gesualdo’s commission of the altarpiece—or if true redemption requires the authenticity of one’s remorse. It is worth noting that Gesualdo intended for his musical composition, Tenebrae Responsoria (1611), to be performed in front of the altarpiece, further enhancing the depth of his plea.8

Carlo Borromeo’s life and work are crucial for understanding Gesualdo’s motivation for featuring his uncle as an intercessor in the altarpiece (fig. 4). Born in 1538 into the influential Borromeo family of Lombardy, which included Pope Pius IV, Borromeo became the Cardinal Archbishop of Milan in 1564, a position of great ecclesiastical power.9 Despite his family’s opulence, Borromeo chose a life of piety, undertaking barefoot pilgrimages across Italy to emphasize his devotion to God, opening his residence in Rome to pilgrims, and washing the feet of the destitute.10 Carlo Borromeo was beatified in 1602 by Pope Clement VIII and later canonized as a saint in 1610 by Pope Paul V. Il Perdono, at the time of its completion in 1609, features a rare instance of a non-divine figure acting as an intercessor with the divine. Gesualdo would have been aware of Borromeo’s canonization before his own death in 1611. Borromeo’s Instructiones Fabricae (Borromean Regulations) provided guidelines for aligning the physical spaces of churches with the spiritual objectives of Catholicism.11 In his treatise, Borromeo emphasizes the importance of using art as a means of educating and inspiring devotion among the faithful. Gesualdo’s commission of Il Perdono adheres to Borromeo’s principles, reflecting a conscious effort by Borromeo to employ art within sacred spaces for both aesthetic and spiritual instruction.

In the later stages of his life, faced with illness, Gesualdo turned to Borromeo’s teachings, demonstrating his piety through acts of artistic patronage. This veneration is evident not only in Gesualdo’s desire to collect his uncle’s relics after his death but also in the prominent role Borromeo plays in Il Perdono. In correspondence with his cousin, Cardinal Federico Borromeo, Gesualdo requested a portrait of Carlo Borromeo and any relics that might alleviate his ailments. He received a portrait in 1611 and a sandal in 1612, along with additional relics. In a letter dated August 1, 1612, Gesualdo expressed his gratitude, stating:

I could not have expected or received a more precious or desired favor today from the kindness of Your Illustrious Lordship than what you graciously granted me with the sandal that the glorious San Carlo wore pontifically. I greeted and kissed it with great joy and consolation, but it will be preserved and held with due respect and devotion.12

This exchange underscores Gesualdo’s profound reverence for Borromeo and his commitment to seeking solace through relics associated with his uncle’s sanctity. Catherine Deutsch attributes Gesualdo’s fervor in obtaining these relics to his intention to erect a chapel for Borromeo at Santa Maria delle Grazie in the town of Gesualdo. In this devotional context, Gesualdo’s commission of the altarpiece emerges as a crucial element in his overarching plan for salvation, as he sought to honor his uncle while also seeking expiation for his own soul.

Gesualdo’s commission of Il Perdono reflected the influence of Carlo Borromeo’s Instructiones, which emphasized strict guidelines for creating sacred images that align with ecclesiastical practices and historical accuracy. Borromeo insisted that sacred art must avoid false or obscene representations, stressing the need to inspire piety:

... nothing false, uncertain or apocryphal should be represented, nothing superstitious, unusual, so too will be strictly avoided all that is profane, shameful or obscene, dishonest or lewd; and likewise all that is extravagant, that does not inspire men to piety, or that could offend the soul and the eyes of the faithful.13

Gesualdo’s Il Perdono served as both a personal expression of piety and a means of cultivating devotion among the faithful while adhering to Borromean principles. The altarpiece underscores the religious and instructive value of sacred images, reinforcing that such artworks should inspire reverence rather than merely serve aesthetic purposes. As Maurizio Vitta notes, Borromeo prioritized the religious significance of images over their formal qualities, insisting they avoid errors that could be exploited by Reformers.14

Most scholars have interpreted the altarpiece Il Perdono as an emotive and didactic tool reflecting Gesualdo’s desire for expiation.15 However, this view is not universally accepted. Annibale Cogliano, from the Carlo Gesualdo Study and Documentation Center, argues that Gesualdo’s motivations for commissioning the altarpiece and establishing two churches were less about atonement and more about family legacy and status. He asserts that the connection between the altarpiece, the churches, and Gesualdo’s past crimes is tenuous, suggesting that his acts of patronage stemmed from a desire for grandeur rather than a genuine quest for forgiveness.16 Cogliano posits that the interpretation of Il Perdono as a “canvas of forgiveness” emerged from a 19th-century rediscovery of Gesualdo, fueled by literary and religious figures captivated by his history of murder and innovative music. These individuals infused a contemporary romanticism into Gesualdo’s narrative, creating a redemptive lens through which to view the altarpiece. The religious atmosphere in southern Italy in Gesualdo’s time was deeply ingrained in everyday life, suggesting a “contractual aspect” to a sinner’s relationship with divinity, which diminishes the significance of Gesualdo’s altarpiece as a tool for expiation.17

In contrast, musicologist Glenn Watkins highlights the significance of the saints depicted in the altarpiece, all of whom faced and overcame demons, suggesting that Gesualdo’s intent was to surround himself with intercessors. Watkins presents a psychological profile of Gesualdo, linking his quest for redemption to the lyrics of his motets. He argues that, as Gesualdo reflected on his life, he recognized the insufficiency of time to enhance his legacy or erase past sins.18 Consequently, Gesualdo sought divine pardon through the commissioning of the altarpiece and by releasing his most mature musical works—Sacrae Cantiones I and II (1603) and Tenebrae Responsoria (1611)—previously kept private. Watkins views this decision as integral to Gesualdo’s pursuit of absolution in his final years.

Both Cogliano and Watkins focus narrowly on the altarpiece and only one other aspect of Gesualdo’s patronage. Cogliano examines patronage trends in early modern southern Italy, while Watkins emphasizes Gesualdo’s sacred music. This limited scope overlooks the interplay between Il Perdono, Gesualdo’s music, and architecture, particularly in relation to his complex relationship with Borromeo. Exploring these interconnected elements reveals richer dimensions in Gesualdo’s pursuit of redemption and illuminates the intricate links between his artistic endeavors and acts of patronage. Gesualdo’s altarpiece embodies the convergence of themes from Borromeo’s Instructiones, his own musical compositions, and fears of damnation, thereby encapsulating the complexity of his spiritual journey. Just as Borromeo’s Instructiones advocated for active participation in liturgical worship, Gesualdo’s altarpiece stands as a tangible manifestation of his quest for reconciliation and redemption. Additionally, Gesualdo composed and published a collection of sacred music intended for performance before the altarpiece.

Commissioned by Gesualdo himself, the altarpiece invites viewers into a contemplative space where themes of sin, repentance, and salvation converge, echoing the spiritual depth found in Gesualdo’s music and the teachings of Borromeo. Contrary to Cogliano’s assertion that Gesualdo commissioned the altarpiece and churches merely to enhance his family name, his various commissions and musical works collectively reinforced his plea for redemption.19 By integrating a program of sacred music in front of Il Perdono in the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Gesualdo orchestrated a harmonious alignment of his artistic endeavors, enhancing the resonance and emotional impact of his plea. The interconnectedness of Gesualdo’s artistic endeavors illuminates the fervency of his quest for redemption. Each distinct work—musical compositions, architectural projects, and visual art commissions—contribute to the multifaceted nature of his supplication. Gesualdo’s endeavors represent a type of expiative plea, highlighting the ambiguous question of whether one can attain salvation through artistic devotion, while leaving us to ponder the sincerity of his quest for forgiveness—an answer that may remain forever elusive.

____________________

William Chaudoin holds a BA in Italian from Vassar College and an MA in Art History from the George Washington University, where his research focused on the early modern period in southern Italy. His scholarship explores the ways in which art and architecture served as mediums of devotion and social influence.

____________________

1. Cecil Gray and Peter Warlock, Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa, Musician and Murderer (Greenwood Press, 1971); Glenn Watkins, The Gesualdo Hex: Music, Myth, and Memory (W.W. Norton, 2010); Catherine Deutsch, Carlo Gesualdo (Bleu Nuit Éditeur, 2010).

2. Watkins, Gesualdo Hex, 14.

3. The Gran Corte della Vicaria found Gesualdo innocent of a crime, with the report of the crime cataloged in the Archivio di Stato di Napoli. In The Gesualdo Hex: Music, Myth, and Memory (2010), Glenn Watkins examines how the cultural narrative surrounding the murder and Gesualdo’s reputation has cast doubt on the veracity of certain details, particularly the alleged trap set to catch his wife with her lover and the brutal nature of the murder itself.

4. Deutsch, Carlo Gesualdo, 64.

5. Watkins, Gesualdo Hex, 20.

6. The Council of Trent (1545–1563) significantly reshaped Catholic practices and the production of devotional imagery by emphasizing the role of sacred images in educating the faithful and reinforcing doctrinal orthodoxy. As G. T. Harper notes in Carlo Borromeo’s Itineraries: The Sacred Image in Post-Tridentine Italy (2018), the Council’s directives led to a more controlled and didactic approach to art, ensuring that religious images were clear, accessible, and aligned with the reforms of the Catholic Counter-Reformation.

7. Glenn Watkins interprets this depiction as representing purgatory, though the flames and the opening in the scene bear a striking resemblance to the imagery of Hell, particularly the traditional iconography of the mouth of Hell. Regardless of the specific realm depicted, this vision represents a fate that Gesualdo sought to avoid, reflecting his deep fear of divine retribution.

8. Watkins, Gesualdo Hex, 62.

9. Pope Pius IV (1499–1565), born Giovanni Angelo de’ Medici, was the uncle of Carlo Borromeo and played a pivotal role in the Catholic Reformation. His papacy was marked by the continuation of the Council of Trent, which was instrumental in shaping Catholic doctrine and liturgy in response to Protestant challenges. Pius IV’s influence and support were crucial in advancing the career of his nephew, Carlo Borromeo, within the church.

10. Anne H. Muraoka, The Path of Humility: Caravaggio and Carlo Borromeo (Peter Lang, 2015), 54.

11. Borromeo’s Instructiones Fabricae Et Supellectilis Ecclesiasticae was first published in 1577 and stands as the only Tridentine treatise that deals with architecture. For more on its significance, see Robert Sénécal, “Carlo Borromeo’s Instructiones Fabricae Et Supellectilis Ecclesiasticae and Its Origins in the Rome of His Time,” Papers of the British School at Rome 68 (2000): 241-67.

12. Deutsch, Carlo Gesualdo, 129. Translated from French by the author. Original French: “Je ne pouvais attendre ni recevoir aujourd’hui de la bonté Votre Seigneurie Illustrissime une grâce plus précieuse, ni plus désirée que celle que vous avez daigné me faire avec la Sandale que le glorieux saint Charles utilisait pontificalement. Je l’ai accueillie et embrassée avec une grande allégresse et consolation, mais elle sera conservée et tenue avec la vénération et la dévotion qu’il convient.”

13. Charles Borromeo, Stefano Della Torre, and Massimo Marinelli, Instructionum fabricae et supellectilis ecclesiasticae: libri II Caroli Borromei (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2000), 71. Translated from Italian by the author. Original Italian: “Inoltre, nel dipingere o scolpire sacre immagini, come non si dovrà rappresentare nulla di falso, di incerto o apocrifo, di superstizioso, di insolito, così si eviterà rigorosamente tutto ciò che sia profano, turpe o osceno, disonesto o procace; e analogamente si eviterà tutto ciò che sia stravagante, che non stimoli gli uomini alla pietà, o che possa offendere l’animo e gli occhi dei fedeli.”

14. Maurizio Vitta, "La Questione delle Immagini nelle Instructiones di San Carlo Borromeo," in Instructionum fabricae et supellectilis ecclesiasticae: libri II Caroli Borromei, eds. Charles Borromeo, Stefano Della Torre, and Massimo Marinelli (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2000), 390. Translated from Italian by the author. Original Italian: “Ciò che dunque sta a cuore al Borromeo—come lo era stato ai Padri conciliari—non era il carattere formale delle immagini, ma il loro valore religioso. Data per scontata la natura eminentemente informativa e didattica di esse, era necessario accertarsi che nulla nella loro configurazione potesse aprire un varco all’errore o prestare il fianco agli attacchi dei Riformati. Solo in questo senso vanno intese le minuziose indicazioni circa le figure da accettare o da rifiutare, gli attributi dei santi o il decoro degli atteggiamenti, delle vesti e degli ornamenti.”

15. Many scholars, including Alfredo Bosi, Cecil Gray, Catherine Deutsch, and Antonio Rattalino, have interpreted Il Perdono di Gesualdo as an emotive and didactic tool reflecting Gesualdo’s desire for expiation and redemption through artistic patronage. This view aligns with the broader understanding of the altarpiece as a visual manifestation of Gesualdo’s complex psychological state and religious zeal. However, not all interpretations agree with this view, with some scholars offering alternative readings of the work’s significance and its role in Gesualdo’s patronage within the context of Post-Tridentine religious reform.

16. Annibale Cogliano, “La pala del perdono: topos della seconda metà del XIX secolo,” Centro Studi e Documentazioni Carlo Gesualdo. http://carlogesualdo.altervista.org/pagine/pala_perdono.htm.

17. Cogliano, “La pala del perdono: topos della seconda metà del XIX secolo.”

18. Watkins, Gesualdo Hex, 89-90.

19. Cogliano, “La pala del perdono: topos della seconda metà del XIX secolo.”

Chicana/o/x Spiritual Memories: Layering in the Digital Print Work of Amalia Mesa-Bains

by Gilda Posada

Amalia Mesa-Bains was one of the first Chicana artists to work with digital print. I interpret Mesa-Bains’s printmaking process as a contemporary Chicana/o/x amoxtli, or manuscript. Reading Mesa-Bain’s printworks as an amoxtli that holds sacred memory and knowledge speaks to how Chicana/o/x artists like Mesa-Bains are rebuilding and rewriting the sacred books of knowledge that were burned by the Spanish conquistadores when they arrived in Mexico in 1519. Mesa-Bains’s printworks serve as a pathway for Chicana/o/x Indigeneity to exist in the past, present, and future, but more importantly, they demonstrate how Indigenous-matriarchal ancestral knowledge could be used to heal contemporary Chicana/o/x experiences in a neo-colonial society.

Before European contact with the Americas, the Mexica and surrounding Indigenous peoples in the Central Mexican Valley used pictorial manuscripts, called amoxtli, to document their understandings of the world and themselves. These amoxtli recorded information regarding Mexica ontology, cosmology, and epistemology, relating information on their creation story, history, science, homeland, government, census, tribute, and sacred ceremonies and rituals.1 When the Spanish arrived in Mexico, they quickly learned that amoxtli and the sacred information within were housed in Mexica temples and government buildings. Thus, as part of their conquest, the Spanish burned or destroyed many of these manuscripts. Those that survived the early conquest were later burned by priests or Catholic church officials who saw the information in the codices as evil and in conflict with their conversion aims for the Indigenous peoples. Today, only fifteen known pre-conquest manuscripts survive. However, some early colonial Spanish friars and priests attempted to preserve the aspects of Mexica life captured in burned amoxtli by transcribing oral histories and tasking Mexica scribes with illustrating these manuscripts.2 Over five hundred of these early colonial manuscripts survive, the most famous of which is Bernardino de Sahagún’s work with the Florentine Codex (1577). This essay concerns a lesser-known early colonial codex, the Codex de la Cruz-Badiano (1552), also known by its colonial names, Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis Badianus or the Badianus Manuscript: An Aztec Herbal.3

Amalia Mesa-Bains’ work, Badianus Botanicals: Bracero, is from her series Badianus Botanicals, which takes its name from the 1552 Codex. Badianus Botanicals: Bracero is a reclamation and remembrance of the Indigenous medicinal ancestral knowledge found in the Codex de la Cruz-Badiano. By layering imagery of remedies from the codex with contemporary imagery of braceros and the Southwestern United States landscape in her print work, Mesa-Bains offers a map that invites Chicana/o/x peoples to find the fragmented pieces of their body, mind, and spirit that they have lost or forgotten due to colonial violence. Amalia Mesa-Bains states:

To understand the artwork that is inspired by sacred sources it is important to establish the concept of memory. The relationship of memory to history is the connection between the past and the present, the old and the new. For the Chicana/o community there is no absence of memory, rather a memory of absence constructed from the losses endured in the destructive experience of colonialism and its aftermath. This redemptive memory heals the wounds of the past. Memory can be seen as a political strategy in work that reclaims history for the community. In a sense the art making inspired by the remembrances of the dead, the acts of healing and the reflections of the sacred can be seen as a politicizing spirituality.10

Badianus Botanicals: Bracero is a visual politicization of Chicana/o/x Indigenous-spirituality (fig. 1). The central figures in the print are three braceros, who are pictured in black and white. Braceros were Mexican exchange workers who came to the United States as part of the Bracero Program, which was in place from 1942 to 1964. The program contracted 4.5 million Mexicans to take temporary agricultural work in the United States. The Bracero Program had an important effect on the business of farming in the United States, yet braceros faced a significant amount of abuse and exploitation while participating in the program.11 This mistreatment of the Bracero Program laid the foundation for the Chicana/o/x agricultural worker exploitation that took place in the 1960s across the Coachella Valley and Central Valley of California, which would ultimately lead to the creation of the United Farm Workers Union in 1966.12 By centering braceros in her work, Mesa-Bains is recalling the laws, histories, and colonial violence that have been imposed onto the brown Indigenous body. The mostly forgotten Bracero Program was rooted in the commodification and dehumanization of the Indigenous body, whose worth was only measured in terms of its labor.

The invisibility of women in this print is intentional, as many of the braceros’s families were left in Mexico. Today, similar socio-economic hardships and immigration policies continue to be the reasons behind family separation and for the militarization of the United States-Mexico border. Neo-colonial policies such as the North American Free Trade Agreement, drug violence, armed conflict, and corrupt governments in Latin America backed by the United States continue to force the migration of Indigenous peoples from Mexico and Central America toward the United States. Violence, dehumanization, and oppression of the Indigenous body might be more visible when it comes to working conditions, but family separation and continued forced migration practices that cause people to be removed from their ancestral homelands are also forms of continued colonial violence. Indigenous women are often the ones left to carry the consequences, especially when the majority of their husbands migrate to the United States as a means of survival in order to send money back home to their wives and children. In Mesa-Bains’s print, the image of the braceros is in black and white, signaling a collapsing of time between the past and present day, where family separation persists due to neo-colonialism continuing to force migration of Indigenous peoples. The braceros become a marker of time, a proof of existence in this print. The past and present come together to make them the main characters of the story that Mesa-Bains is telling, and there is no erasure of their existence or their humanity in this contemporary amoxtli.

Amalia Mesa-Bains offers a remedy to the pain that her community continues to endure by remembering her Indigenous-ancestral healing practices in the form of images from the Codex de la Cruz-Badiano. Specifically, she references images from Plate 22 , which depicts three different medicines, each of which are laid over a different bracero (fig. 2). They are macayelli, xoxouhquipahtli seeds, and tlaquilin leaves, which, when combined, provide medicine for ear pain. This information is written in Latin under the drawing of the herbs on Plate 22, with detailed instructions for their preparation and use.13

In her print, Amalia Mesa-Bains keeps the Latin portion of the original manuscript but relocates the text to the top of the print. Additionally, she changes the color of the ink in which it is written. Instead of the original brown ink, Mesa-Bains uses a transparent white ink that fades into the background of the print. This white color directly connects to the bracero figures. When seen together, the two become one, implying that Mesa-Bains is creating a link between two different moments in time. There are several ways to interpret their unity. The first is that Mesa-Bains is offering medicine to the braceros who are in pain, the second is that she is offering them healing for their exploitation and dehumanization at the hands of colonial powers. A third interpretation is that she is offering medicine to American citizens who have fallen deaf to the cries of these neo-colonial victims, medicine for them to open their ears and bear witness—if not act—to the cries of those who are in pain due to their exploited labor in both the past and present.

The use of Latin points to the ongoing violent histories of European colonialism in Mesoamerica. Mesa-Bains visualizes the blood and destruction that the Catholic church has on their hands by deploying the language used to justify violence and forced assimilation for Chicana/o/x peoples. Elsewhere, she uses Nahuatl in her print to honor the Indigenous medicine and her ancestral connection to Indigenous knowledge. The tension of being caught between worlds can be seen in the text overlayed on the remedy instructions. In red font Mesa-Bains writes, “In the condition of displacement we experience our own landscape of longing. They are the sites of memory and spirituality that sustain us in times of extremity and loss.” She is acknowledging the losses caused by displacement and the transformation of Indigenous peoples into proletarianized subjects on the settler-colonial stage. At the same time, she points to the resilience and endurance of Indigenous peoples despite colonial destruction. Mesa-Bains is calling ancestral memory and spirits who have walked on this land to be the primary tool for Chicana/o/x peoples to survive. However, it is that same spirit that needs the medicine to heal and continue to endure.

The remedy that Mesa-Bains chose for this print is one which is vital to cure as soon as the illness begins because it can cause susto or loss of tonalli.14 According to Mexica belief, tonalli, or life-force, lives in the head.15 An individual can slowly lose their tonalli and eventually perish through susto, or spiritual fright, that enters the body through their mouth, ears, or eyes.16 The remedy that Mesa-Bains brings forward is categorized as a cure for remedying the tonalli due to a sickness in the ears, one that must be applied quickly. Mesa-Bains is directing the viewer’s attention to the sense of hearing and listening especially as it relates to susto and the “memory of absence.”17 By visually layering painful Chicana/o/x histories, imagery of colonialism, and the physical exploitation of Chicana/o/x peoples, Mesa-Bains is reminding the viewer that the memory of colonialism is not lost, but rather that to change the condition of the present and future, one must heal the trauma or susto that has been inflicted onto the Indigenous body throughout centuries of violence. She is providing relief to the ears and restoration of spirit or tonalli for those that live with pain due to the physical, mental, and spiritual exploitation they face. However, it is important to note that the remedy selected by Mesa-Bains is one that requires daily treatment and calls for all aspects of a plant's life cycle to be used: seeds, leaves, bushes, and roots. It also requires that the plants be taken through various transformations before they can be used as a cure, such as cutting, boiling, grinding, and rubbing. With this, Mesa-Bains is signaling that healing and restoring the tonalli will not be easy and that it will be a long and hard process. She is pointing to the importance of listening to past experiences so that future Chicanas/os/xs will not forget and instead learn from the experiences, memories, and spirits of their ancestors.

In Badianus Botanicals: Bracero, the landscape also reveals one last important layer to the Chicana/o/x experience: that of mother earth, who gave birth to Chicana/o/x-Indigenous ancestors. The landscape in this print is from a United States-Mexico border crossing desert region, identifiable by the topography and flora depicted in the background. The cacti are reminiscent of the creation story of the Mexica, who spent hundreds of years on a journey across the United States Southwest and Northern Mexico desert regions being guided by Huitzilopochtli to the place where they would establish their homelands.18 By including the Southwest desert, Mesa-Bains is not only reminding Chicanas/os/xs of their Indigenous ancestry tied to a place and time, but also the contemporary pains caused by the displacement of Indigenous peoples from their homelands across the global South. Badianus Botanicals: Bracero is an amoxtli and pictorial reminder that the relationship between humans and land is the medicine that will keep the Chicana/o/x spirit and peoples moving forward despite the hardships that they continue to face.

____________________

Gilda Posada is a Xicana art historian, artist, and curator from Southeast Los Angeles. She received her AB from UC Davis and her MFA and MA in Visual and Critical Studies from California College of the Arts. Currently, Gilda is a PhD candidate in History of Art at Cornell University.

____________________

1. Elizabeth H. Boone, "Central Mexican Pictorials,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures, ed. Davíd Carrasco (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 155-158.

2. María Elena Briseno, “Códices: Los antiguos libros del nuevo mundo,” in Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 24, no. 81 (Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México 2002): 175-178. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0185-12762002000200008&lng=es&nrm=iso.

3. The Codex de la Cruz-Badiano is known by several names such as: Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis Badianus, Badianus Manuscript, and Codex Barberini.

4. “The Badianus Manuscript,” World Research Foundation. http://www.wrf.org/ancient-medicine/badianus-manuscript-americas-earliest-medical-book.php.

5. EC Del Pozo, “Prefacio,” in Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis, by Martín De la Cruz, trans. Juan Badiano (Mexico City: Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, 1964).

6. Andrés Aranda et a,. “La materia medica en el Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis,” Revista de la Facultad de Medicina 46, no. 1 (2003): 13. https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/facmed/un-2003/un031d.pdf.

7. The sequence of the remedies starts with the head and ends at the feet, signaling some correspondence to the thirteen upper worlds, and seven underworlds that the Mexica believed ruled all forces and beings.

8. Carlos Viesca T. and Andrés Aranda, “Las Alteraciones del Sueño en el Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis,” Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl 26 (December 27, 1996): 156.

9. Carlos Jair García-Guerrero and Feliciano Blanco-Dávila, “La cirugía plástica y el Códice De La Cruz-Badiano,” Revista Medicina Universitaria 6, no. 22 (2004): 52.

10. Amalia Mesa-Bains, "Spiritual Visions in Contemporary Art," in Imagenes E Historia/Images and Histories: Chicana Altar-Inspired Art, eds. Constance Cortez and Amalia Mesa-Bains (Medford, MA: Tufts University, 2000), 2.

11. "Opportunity or Exploitation: The Bracero Program,” The National Museum of American History. http://amhistory.si.edu/onthemove/themes/story_51_5.html.

12. From 1953-1954 concerns were raised across states that held a large bracero presence, such as Texas and California. The concerns were due to assimilation resistance coming from bracero and Mexican immigrants, along with the large number of border crossings occurring during an economic decline in the United States. Additionally, the end of the Bracero Program on December 31, 1964 set the baseline for many other immigration policies in the United States, such as Operation Wetback, Operation Gatekeeper, and the formation of the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service.

13. Translation from William Gates 1939 publication: Festering in the ears will be helped the most by instilling the root of the maza-yelli, seeds of xoxouhqui-patli plant, some leaves of the tlaquilin with a grain of salt in hot water. Also the leaves of two bushes, rubbed up, are to be smeared below the ears; these bushes are called tolova and tlapatl; also the precious stones tetlahuitl, tlacahuatzin, eztetl, xoxouhqui chalchihuitl, with the leaves of the tlatanquaye tree macerated in hot water, ground together and put in the stopped up ears, will open them.

14. Aranda et al., “La materia medica en el Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis,” 17.

15. Maarten Jansen and Gabina Aurora Pérez Jiménez, “Time and the Ancestors,” in The Early Americas: History and Culture, eds. Corinne L. Hofman and Maarten E.R.G.N. Jansen Vol. 5 (Boston, MA: Brill, 2017), 18-19.

16. Teresa Cupryn, “La expresión cósmica de la danza azteca,” Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales 37, no. 147 (1992): 45.

17. Mesa-Bains, "Spiritual Visions in Contemporary Art,” 2.

18. Patricia Chicueyi-Coatl Juarez, “How to Read Amoxtin,” Online Workshop UC Gill Tract Community Farm. Albany, California, May 23, 2020.

editor’s introduction

by Toni Armstrong

If secrets are a form of social currency, then the history of art has a wealth of treasure to be discovered. Secrets have long been a form of community building, as those “in” a given circle are allowed to know and those “outside” are kept in the dark. The word secret comes from the Latin meaning “to separate,” and secrets often do exactly that: separating truth from fiction, separating trustworthy confidants from suspects, and separating conspicuousness from mystery. There are many secrets in the archives and hidden within the works of art we study. Some of these secrets were made through acts of censorship or neglect, while others were made by artists choosing to protect themselves. Yet other secrets were created inadvertently when a gap in knowledge left something unspoken between two generations or when records of a creator’s own interpretations ceased to exist.

From x-ray technologies that reveal the “secrets” hidden in art to public writing on the “secrets” of art-making, concealment and its revelations play an unavoidable role in our work as scholars, artists, and art historians. We act as detectives when we research: combing through archival and curatorial records, looking at art objects, and theorizing about the world and our histories. When we publish our findings, we allow these secrets—whether intentionally or accidentally hidden—to have a scholarly voice and be rediscovered by new audiences.

There is a series of secrets embedded in Rogi André’s 1940 portrait of Peggy Guggenheim (fig. 1).

When scholars open Guggenheim’s story in New York, they neglect the fact that she spent years living in Paris among these artists, building the social network that would allow her to become so successful so quickly back in New York. In André’s photograph, Guggenheim poses in the artist Kay Sage’s apartment, where she stayed after Sage fled Paris for the United States a few months prior. Guggenheim has intentionally surrounded herself with works she has recently collected: Constantin Brancusi’s polished bronze sculpture, Maiastra (c. 1912) and Robert Delaunay’s Fenêtres ouvertes simultanément (1912). In other photographs in this series, Guggenheim and André posed Brancusi’s sculpture with her, indicating that Guggenheim felt it was an important indicator of her taste, perhaps specifically her interest in high abstraction. Yet more details are embedded in this image that demonstrate Guggenheim’s self-fashioning as an art patron: there are two 1934 issues of the surrealist magazine Minotaure beside her, while Guggenheim holds a third featuring Marcel Duchamp’s Rotorelief no. 7 (1935).3 Choosing to place herself among these objects for this photograph demonstrates to the viewer—and the historian—that Guggenheim was already imagining herself as an important modernist patron well before she left Paris. When she arrived in New York shortly after this photograph was taken, she brought both the objects around her and the connections they represented.

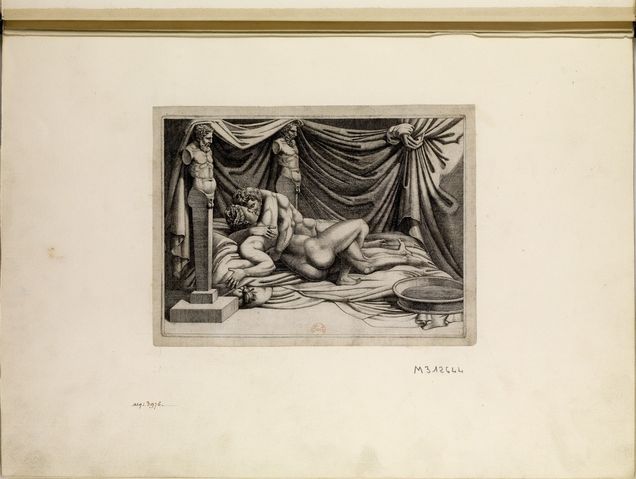

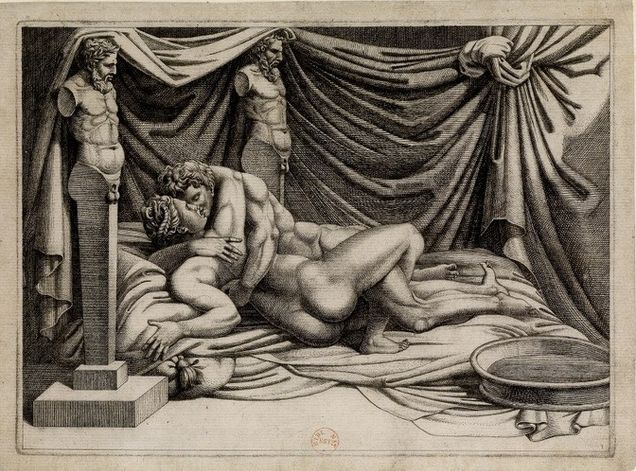

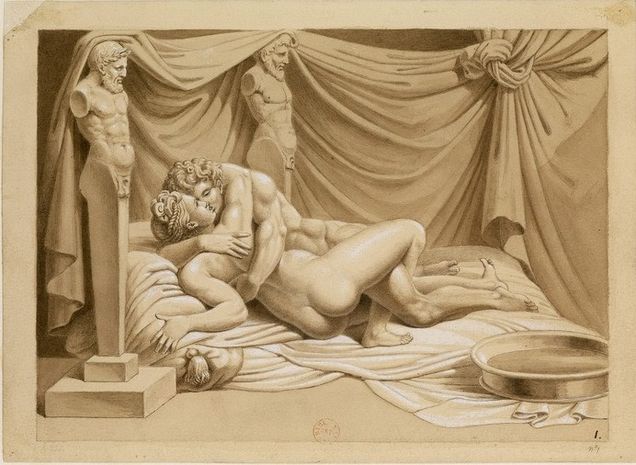

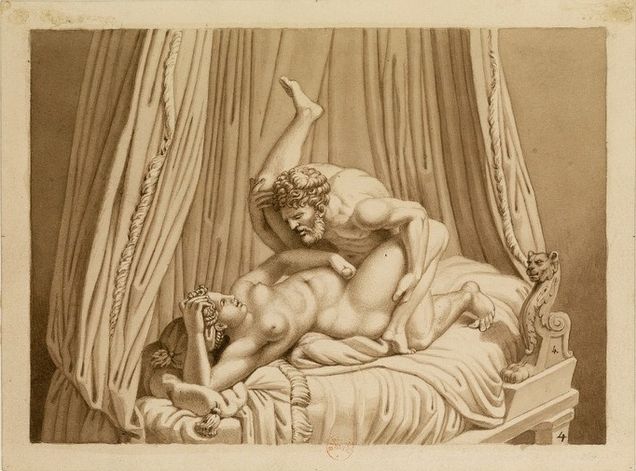

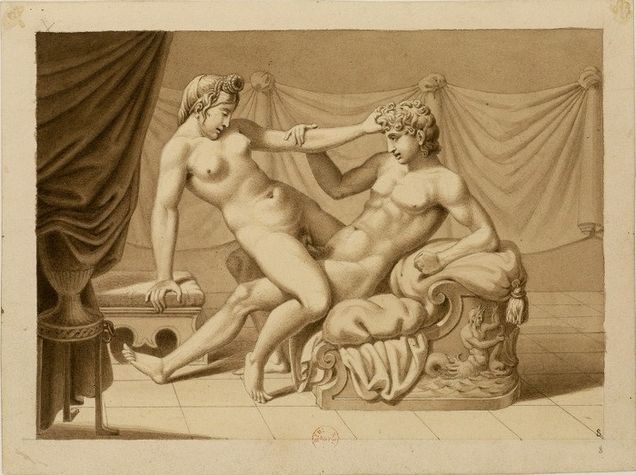

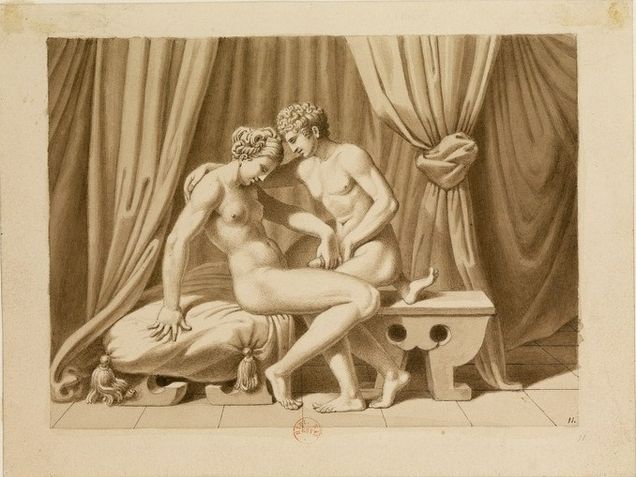

As stories move through history, they pick up new details. Once finally given voice, their meaning has changed. The two feature essays included in this issue deal with this question of how visual art becomes layered as it is reprised through time. To analyze the contemporary prints of Amalia Mesa-Bains, Gilda Posada unravels multiple layers of history; she analyzes the sixteenth-century Codex de la Cruz-Badiano, an important pictorial manuscript on Mexican and Indigenous botany and medicine and distills the violent history of the twentieth-century Bracero Exchange Program. Thus, when Posada turns to her reading of Mesa-Bains’ prints, she shows how this fraught history is embedded in each contemporary image, too. In our second feature essay, Iakoiehwahtha Patton examines how a series of controversial erotic images, I modi, were equally disseminated and censored in the years following their publication in early modern Italy. Reactions to the titillating novelty of I modi, increasing efforts to control the image of the nude, and anxieties about viewers’ reactions to the images led to a papal censorship campaign against the prints.

In parallel with the work undertaken in our feature essays, two exhibition reviews demonstrate how artists and curators alike grapple with storied historical legacies. Corey Loftus explores how artist Jessica Campbell reprises the history of a 1920s women’s activist society, the secretive Heterodoxy Club, through rich textile art in an exhibition at the Fabric Museum in Philadelphia. Loftus makes visible the connections between the Heterodites’ activist work and publishing and Campbell’s engagement with the archive. Although a less direct challenge to the archive, Miray Eroglu’s essay on Partisans of the Nude, an exhibition at Columbia University, shows how this exhibition offers an important addition to the narrative of both modernism and twentieth-century Arab art. Eroglu demonstrates the multiple meanings of the nude—as a site of personal reflection, a political act, a space of collectivity—for both the artists and their audiences.

As we produce new scholarship, we are all finding new methods for “telling” these complicated and layered secrets. Shawn Simmons reviews Dragging Away: Queer Abstraction in Contemporary Art to show how Lex Morgan Lancaster’s notion of “queer abstraction” offers an analysis of abstract art production without concrete boundaries or inflexible interpretations. Instead of crafting a singular definition of abstraction, Simmons lauds Lancaster’s capacity to uncover layers of meaning and multiple modes of visibility in abstract art.

Our two research spotlights demonstrate new methods for writing about aspects of history that are too often under-discussed in scholarship today. Liz Neill describes “The Provenance Reliability Index,” a digital humanities project that tracks the movement of archaic pottery vessels in both the ancient and modern worlds. Through a digital database, Neill demonstrates a model for collecting and sharing data about the displacement of ancient Mediterranean objects from their original findspots that reveals avenues of further contextualization for their mobile lives. With a different method, but a similarly radical approach to how we might create new scholarship, Danielle Wirsansky describes her new musical entitled The Secrets We Keep, which explores Jewish-Polish history during the Holocaust and its aftermath through Slavic folklore. Through this mode of storytelling, Wirsansky offers a new way of engaging the public to expand and share the often painful conversations held in the fields of memory studies and Holocaust studies.

In All About Love, Black feminist scholar bell hooks urges her readers to consider the telling of secrets as a way to reclaim power, to build community, and to protect one another.4 As our authors have shown in this issue, secrets have a way of connecting us inextricably with our pasts. The work of uncovering these secrets requires that we first notice an absence, a mask, or an erasure. The act of telling these secrets—through the production of new scholarship—requires new ways of looking at, thinking about, and writing history.

____________________

Toni Armstrong is a PhD candidate in the History of Art and Architecture at Boston University. Toni works on 19th- and 20th-century art in the United States, with a particular focus on women art collectors, queer and women’s history, and alternative museum practices.

____________________

1. Catherine Gonnard, tr. Katia Porro, “Rogi André,” Dictionnaire universel des créatrices (Paris: Archives of Women Artists, 2019), via AWARE, https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/rogi-andre/.

2. See Mary Dearborn, Mistress of Modernism: The Life of Peggy Guggenheim (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2004) and Emma Acker, “The Maverick Collector: The Method in the Madness of Peggy Guggenheim.” Collections 1, no. 1 (March 1, 2004): 81–100.

3. The Minotaure issues featured are Minotaure no. 6 (December 5, 1934) with a cover by Marcel Duchamp, and Minotaure no. 5 (May 12, 1934) with a cover by Francisco Borès. The open issue may be Minotaure no. 10 (December 1937).

4. bell hooks, All About Love: New Visions (New York: HarperCollins, 2000).

Partisans of the Nude: An Arab Art Genre in an Era of Contest, 1920—1960

Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University in the City of New York

October 6, 2023–January 14, 2024

by Miray Eroglu

Upon entering Partisans of the Nude: An Arab Art Genre in an Era of Contest, 1920–1960, curated by Kirsten Scheid, visitors are greeted with Omar Onsi’s painting À L’Exposition (fig. 1). The painting depicts a group of fashionably veiled Sunni women in an art gallery gathered around a nude painting, perhaps mirroring visitors’ own viewing responses. As such, the nude’s power infiltrates Columbia University’s Wallach Art Gallery. The exhibition features works by twentieth century modernist painters, including Beirut-based Moustapha Farroukh (1901–57), Jewad Selim (1921–61), working in Bagdad, and Amy Nimr (1898–1974), working in Cairo, Paris, and London. The works by these artists, amongst others, shed light on an emergent nude genre that flourished between 1920 and 1960 in post-Ottoman Arab society, from the art salons of Tunis to Cairo and Beirut. Over fifty paintings and twenty drawings are exhibited alongside books, pamphlets, and videos celebrating the nude form, including film stills from Le Marché au Soleil (1930) shown in Beirut. As opposed to being rendered taboo, painted nudes were a source of artistic inspiration both in the studio and in society writ large. In fact, they were thought to represent modernity, increase visibility of women in the social sphere, and emblematize the “modern” repertoire of modernist painters.1 Although painted nudes may have been absent in past painting traditions in the Arab world, nudes became a popular subject matter for Arab artists depicting their present while looking towards a liberated future.

Partisans of the Nude is structured around the overarching themes of art professionalization and gender, identity, visibility, eroticism, and nudity as vehicles of socio-cultural activism (figs. 2-3). In the exhibition, the nude body is rendered in myriad ways, ranging from abstracted and surrealist depictions to aesthetic ideals in line with Western Beaux-Arts traditions, such as Venus pudica figures or women in odalisque poses. The exhibition looks at the various ways in which Arab painters co-opted the European classical nude as a form of artistic activism and self-definition via their participation in the global “Modernist” movement in their respective cities. The painted female nude was important to the burgeoning art scene in newly formed Arab capitals under a Mandate system after the end of the Ottoman Sultanate: the naked–often female–body is placed in dialogue with new fashions, largely progressive social movements, and contemporary modernizing projects worldwide (al-mu'asara).

By including important works by female artists such as Amy Nimr, Sophia Halaby, Saloua Raoda Chocair, Fêla Kefi Leroux, Juliana Seraphim, Munira al-Kazi, Simone Baltaxé Martayan, and Helen Khal, the exhibition explores how artistic identity impacts representations of the nude figure. Paintings of female nudes by women artists consider personal agency, identity, and the female experience as opposed to hetero-masculine viewpoints that objectify the female body to incite desire.

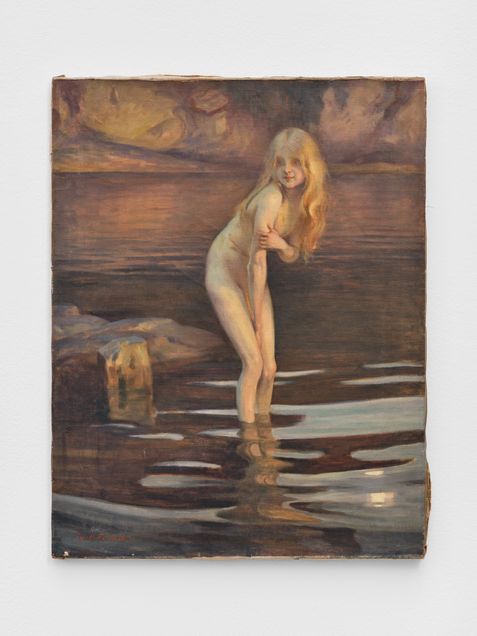

The exhibition features multiple nude figures depicted in interiors and intimate spaces, such as bedrooms and artists’ studios. The nudes inhabit a multitude of coastlines, and the paintings embrace uncertainty, vagueness, and transition across cultural thresholds inspired by the liminality of the shore. Water is featured within many of the compositions, especially in scenes of women bathing in the bathhouse (hamam)—a popular subject which references European Orientalist paintings (fig. 4). Scheid notes in the exhibition text: “Some nudes take cover in bathing or prostitution, others imitate sheer erotic experience.”2 Unclothed figures can thus move between public and private worlds, their nakedness performing a practical aspect of bathing, or representative of their social roles. The display of the naked body, while at times erotically charged, is also often a site of the subject’s personal power.

The nude is also indicative of social worlds. Jewad Selim, working in Baghdad after training at the Slade School of Art in London, expresses anxieties surrounding public sexuality in his painting Women Waiting (fig. 5). Selim localizes and undresses the female form seated on an ottoman in a space recognizable as an interior, therefore offering a glimpse into her private world and her conflicted emotional state. Selim’s painting opposes the belief that a woman’s life is incomplete without marriage. According to Miriam Selim, Jewad Selim’s daughter, her father and other artists in the Baghdad Modern Art Group were “concerned about poverty, illiteracy, and feminist issues” as well as uneducated women who “waited for marriage.”3 Selim’s painting imagines a parallel world for educated and socially involved women, thus transforming the private nude into a collective, social one.

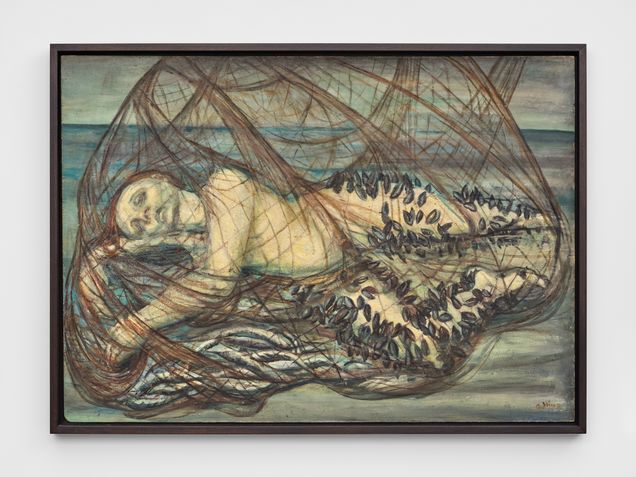

Most of Amy Nimr’s compositions hold personal meaning, often functioning as a way to cope with her grief after the tragic death of her son. Nimr divided her time between Egypt, France, and England, where she received her artistic training, and joined the Surrealist Art and Liberty Group in Egypt in addition to hosting art salons alongside her husband. Nimr’s nymph-like naked female on the beach resembles Moustapha Farrouk’s Au Crépuscule (1929), which is itself modeled on Paul Chabas’ September Morn (1921) (figs. 6-7). While Farrouk, working in Beirut, portrays an idealized and romanticized woman bathing in a pool of water, Nimr visualizes a vulnerable nude woman enveloped in a fisherman’s net. Her eyes are shut, and her body appears lifeless and trapped in contrast to other energetic depictions of the liberated nude body.

The naked body is often hidden from sight. Stripped bare, the nude is also a space to project secrets, desires, narratives, and change. Contemporary viewers of these paintings reported that nude paintings could “enhance awareness of their bodily selves and their deep, libidinal knowledge.”4 Art historian Anneka Lenssen views these paintings as a way of engaging the “imagination of an active, demanding, collective self.”5 In this way, Partisans of the Nude uncovers the concealed worlds of the painted female nudes by spotlighting this often thought to be “hidden” genre of Modernist Arab Art in the early to mid-twentieth-century.6 Viewed together in the gallery space, the nude figures compose a collective body-scape, a sequence in multiple women’s lives—or fantasies—offering opportunities to relate, empathize, and engage with our own physicality.

____________________

Miray Eroglu is a first-year PhD student in Art History at Temple University's Tyler School of Art and Architecture concentrating on Ottoman Art. Miray holds an MA from New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts and a BA Honors in Art History from McGill University.

____________________

1. Kirsten Scheid, “Necessary Nudes: Hadatha and Mu‘asara in the Lives of Modern Lebanese,” in International Journal of Middle East Studies 42 (May 2010), 203-230.

2. Kirsten Scheid, Partisans of the Nude: An Arab Art Genre in an Era of Contest, 1920–1960, exhibition wall text, Wallach Gallery.

3. Kristen Scheid, Jewad Selim, Nisa Fi Al–Intidar (Women Waiting), 1944, Partisans of the Nude: An Arab Art Genre in an Era of Contest, 1920–1960, exhibition wall text, Wallach Gallery.

4. Anneka Lenssen and Kirsten Scheid, Partisans of the Nude: An Arab Art Genre in an Era of Contest, 1920–1960, exhibition wall text, Wallach Gallery.

5. Anneka Lenssen and Kirsten Scheid, Partisans of the Nude: An Arab Art Genre in an Era of Contest, 1920–1960, exhibition wall text, Wallach Gallery.

6. Kirsten Scheid, “Necessary Nudes: Hadatha and Mu‘asara in the Lives of Modern Lebanese,” 203.

Jessica Campbell: Heterodoxy

Fabric Workshop and Museum

October 6, 2023–June 2, 2024

by Corey Loftus

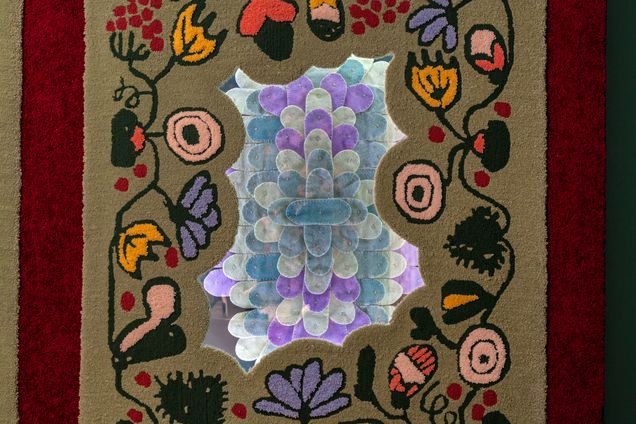

Upon entering Jessica Campbell’s installation in the first-floor gallery at the Fabric Workshop & Museum (FWM), visitors are invited to take a seat. An assortment of antique chairs with blue floral cushions, arranged around three long tables, draw the viewer inward (fig. 1). The room is cozy—in part because of the abundance of fiber-based materials on the gallery’s perimeter, including the bright red fireplace on the rear wall. Canadian artist and cartoonist Campbell fashioned the orange flames, boxy mantle, and even the flowers perched atop the hearth entirely out of commercial carpet and polyurethane foam. On either side, plush tufted panels cover the walls from floor to ceiling. Tufting is a textile manufacturing technique that involves running short pieces of thread “piles” through a taut primary base with a tufting gun (fig. 2). The process produces a surface of densely packed threads that entices the tactile sense. Luckily, the museum offers a textile sample to satisfy viewers overwhelmed with the desire to touch them.