Following Institutional Critique Inside the Library

by Levi Sherman

When artists in the 1960s began challenging systemic authority, it seemed any cultural heritage institution—library, archive, or museum—could be a target of what would become known as Institutional Critique.1 The same period heard the first rumblings of today’s “digital convergence,”2 or the collapse of libraries, archives, and museums into repositories of information, accessed by users with little interest in the distinctions between these types of institutions.3 Yet even as librarians, archivists, and museum registrars blurred into “information professionals” in the 1960s, artists would develop a very different relationship with libraries than with archives and museums. My current research triangulates this unique artist-library relationship through the art historical framework of Institutional Critique, the cultural history of libraries, and the discourse of information science.

I hope to complicate the art historiography of Institutional Critique and glimpse what has been lost when the distinct purposes and practices of libraries, archives, and museums blur into information or institutionality writ large. These blurred boundaries haunt Institutional Critique from its inception in the journal October, which drew heavily from Foucault’s rather abstract understanding of the archive.4 It seems no coincidence that Henry Pisciotta writes from the perspective of a working librarian when he posits an alternative timeline of Institutional Critique, which peaks with the archival turn of the 1990s.5 Where art historians like Blake Stimson distinguish between a generation who tries to hold public institutions accountable and one who tries to redirect private institutions, Pisciotta shows that artists never stop trying to hold libraries to their mission.6

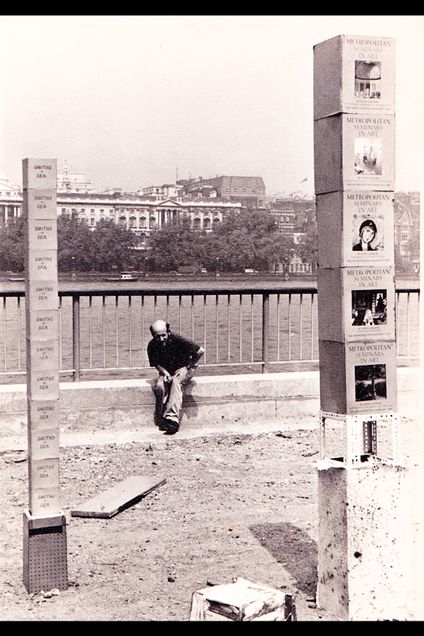

John Latham naturally figures into Pisciotta’s study of the Institutional Critique of libraries. Latham staged his spectacular book-burnings, Skoob Tower Ceremonies (1964–1968), at several institutional sites, like the British Library.7 Figure 1 illustrates another Skoob Tower Ceremony staged in London’s South Bank, with a similar civic architectural backdrop. But few later artists adopt Latham’s approach. Where Latham treats the library—like the museum and the courthouse—as a shallow signifier of culture and authority, later artists perform their critique from inside the institution, often with its permission and support.8 These artists understand the library as an exercise of authority but also democracy. They engage in a nuanced immanent critique that addresses how libraries operate rather than what they represent symbolically.

Beneath its stereotypically neoclassical façade, the modern public library has never been a centralized authority like the archive or museum, which share its spectacular architecture of power. Indeed, library history reveals continued frustration with this decentralized governance within national organizations like the American Library Association.9 Public libraries are accountable to taxpayers, serve amateur researchers, and prioritize information dissemination over preservation or connoisseurship. In other words, the anti-institutional pressure that Stimson associates with “new technologically enabled forms of peer-to-peer social organization” shaped the public library long before digital convergence began.10

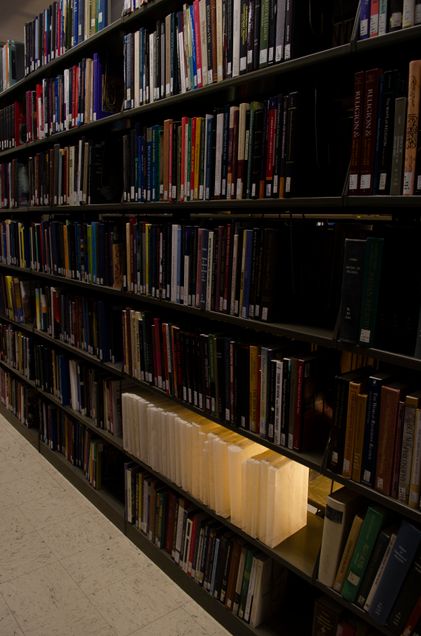

Artists need not intervene in the library’s spectacular trappings—its outward signifiers of culture and authority—because members of the community remain agonistically engaged with the institution’s inner workings. Indeed, the everyday interactions between the library and its patrons are generative points of departure for many artists. One example is India Johnson’s Negative Theology (2019–2020), which converses with a specific library as a site and set of practices (fig. 2).11 Johnson checked out a university library’s complete selection of books on the subject of negative theology and filled their spots on the shelves with fabric casts during the check-out period.12 Thus, the location, scale, and duration of Johnson’s installation are determined by the library’s classification scheme, acquisition plan, and checkout policy. Whereas Institutional Critique artists tended to approach art museums from the position of artists rather than patrons, Johnson’s visit mirrors that of a typical user; anyone can remove books from a library shelf and keep them, thus altering the space within the constraints of the site.

Art history has been better at theorizing generalized modes of site specificity than addressing the operations of a specific site like a public library. My research seeks to understand how artists engage with libraries and their communities of readers by using the tools of library historians like Wayne Wiegand, a people’s historian of libraries: the public and mundane evidence of policies, annual reports, meeting minutes, and letters to the editor.13 Reading Johnson’s immanent critique in the context of library history reveals the decentralized yet highly institutionalized terrain where people continue to encounter actual democracy, not just architectural and artistic spectacle of democracy found outside of the library.

____________________

Levi Sherman is a PhD student in Art History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. With a background in design and interdisciplinary art, he maintains a studio practice and co-operates a small press. Levi’s research interests include walking art, artists’ books, and the broader intersection of contemporary art, books, and libraries.

____________________

Footnotes

1. According to art historian Blake Stimson, “institutions were understood to be the means by which authority exercised itself” and so represented the system of “illegitimate authority” and control, which artists previously located in authoritarian figures like heads of state. Blake Stimson, “What Was Institutional Critique?” in Institutional Critique: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011), 22.

2. Wayne A. Wiegand, Part of Our Lives: A People’s History of the American Public Library (United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2015), 193–194.

3. Cecilia Salvatore, “Libraries, Archives, and Museums in the Twenty-First Century,” in Libraries, Archives, and Museums: An Introduction to Cultural Heritage Institutions Through the Ages (Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2021), 251–260.

4. In framing Institutional Critique, Benjamin H.D. Buchloh and Hal Foster tend to address the idea of the institution rather than its operation. Foster’s 1996 essay “The Archive without Museums” exemplifies this approach, which invokes the library as a Borgesian, Alexandrian thought experiment. Foster does so by blurring Foucault’s respective treatments of the library and the archive, which themselves tend toward the abstract. See Hal Foster, “The Archive without Museums,” October 77 (1996): 97–119.

5. Henry Pisciotta, “The Library in Art’s Crosshairs,” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 35, no. 1 (2016): 2–26.

6. Stimson,“What Was Institutional Critique?,” 37.

7. Elisa Kay, “John Latham,” Flash Art International 44, no. 280 (October 2011): 64–67.

8. Pisciotta discusses examples by Mel Chin, George LeGrady, Clegg & Guttman, and others which reveal different strategies for maintaining a critical edge while collaborating with the institution.

9. One telling example was the ALA “Library Bill of Rights,” which emerged during the Second World War to combat censorship and promote free inquiry. Library historian Wayne Wiegand notes that actually implementing the LBR was “almost always messy, often impossible, and professional consensus… was hard to discern.” Wayne A. Wiegand, Part of Our Lives: A People’s History of the American Public Library (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 166.

10. Stimson, “What Was Institutional Critique?,” 32.

11. India Johnson, “Negative Theology,” India Johnson, accessed October 18, 2022, https://indiajohnson.hotglue.me/?sitespecific/

12. Negative theology, or the study of the divine through what it is not, is no doubt a pun, but the subject also relates to Johnson’s research into the intersection of religion, language, and book art.

13. As municipally funded institutions with public boards, library records are generally more available than those at museums and other private institutions.