Ties That Bind: Hairwork as Family Portrait in the Nineteenth-Century United States

by Victoria Kenyon

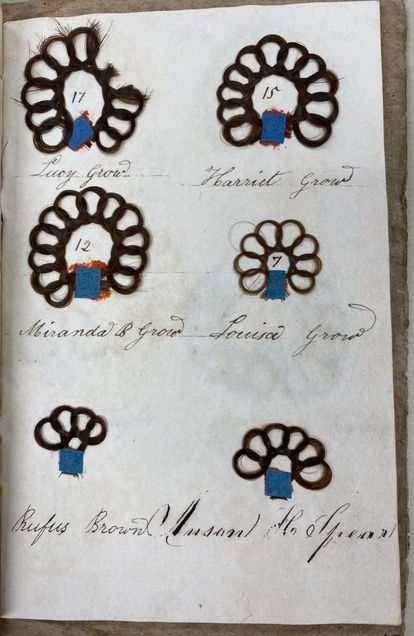

The young artist collected her central material, hair, from people both in and outside of her immediate family. Grow’s placement choices establish family connections and provide crucial context for the way we are meant to read her album. On one page, she depicts herself and her sisters in nearly-identical hair chains inscribed with each girl’s age and arranged from left to right in descending age order (see fig. 1). This arrangement suggests the format of the family tree, the botanical iconography of which goes back to the Tree of Jesse motif in Christian Medieval and Early Modern Europe.5 Such documents and other genealogical records, including family registers, were historically important to establishing familial connection. Karin Wulf has examined the religious and political implications of familial genealogy in British America, noting the reflection (and indeed support) of white, patriarchal systems of inheritance in the practice of listing one’s family members and recording events such as marriages, births, and deaths in record books and family bibles.6 As in hairwork, there was an element of sentimentality in the emotional connection evoked through documenting one’s family, as well as a didactic quality. Though apparently not a necessary component, some such documents also included physical likenesses of individuals alongside names, as evidenced in an 1875 Vermont marriage certificate (fig. 3).

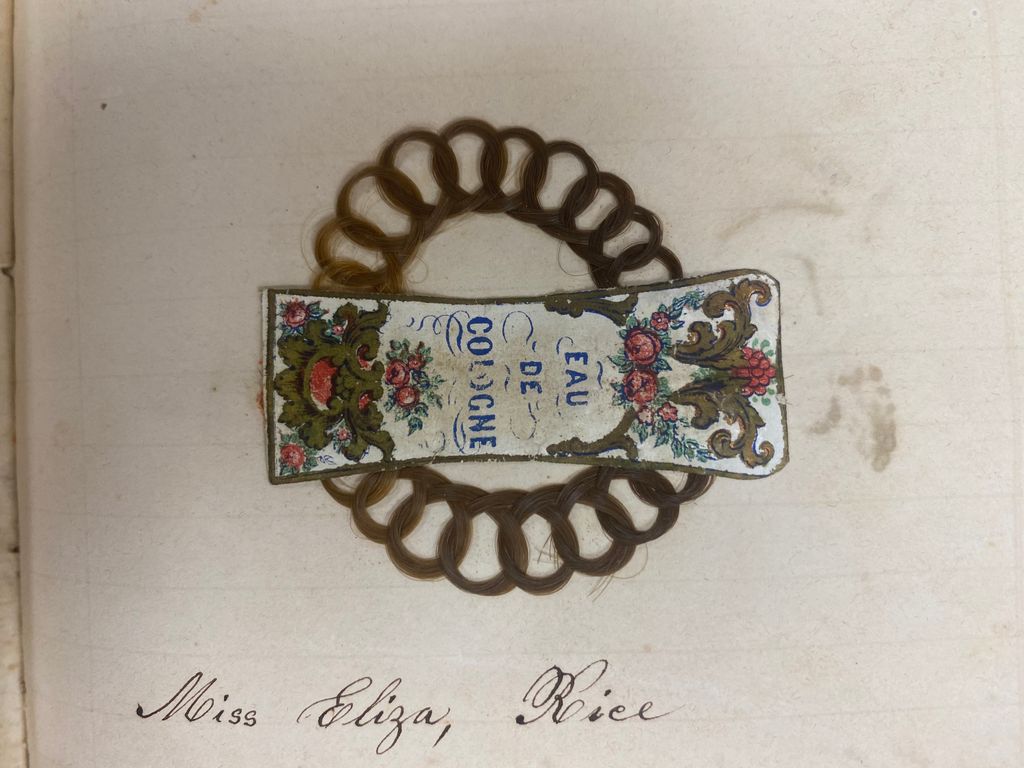

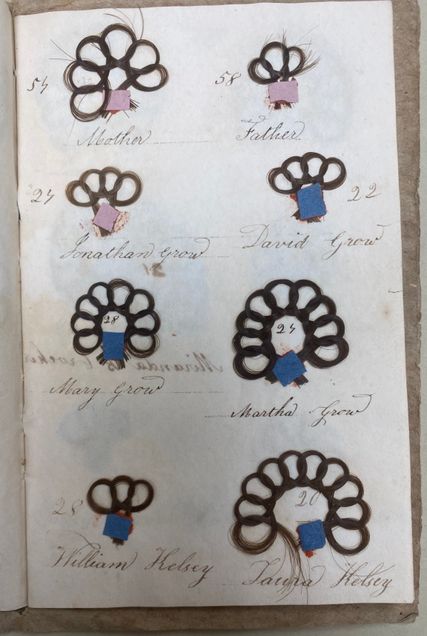

Grow’s medium does not provide as direct an image of a person as would a photograph, but her portraits reveal some facets of appearance that photos or other media could not, including the full tonal ranges of a person’s hair. There may have even been an olfactory component to the objects; another nineteenth-century album, made by Louisa Rice of Paradise Township, Pennsylvania, included a perfume label in a hair portrait of the artist’s sister (fig. 4). Coupled with the fact that period advice guides directed young women to perfume their hair, this suggests that Louisa Rice may have applied the perfume to which the label belonged to that hair portrait, and Grow may have similarly scented her objects to strengthen the connections between individual and portrait.7 Grow also creatively shows physical differences in the sisters’ portraits in figure 1; the youngest’s (Louisa, 7) is noticeably smaller. Grow continually groups family members together in her album. Another page depicts her parents and some of their children, though Lucy herself is missing; the Kelseys, included at the bottom of the page, may have been Grow family cousins, as they shared a house with the Grows (fig. 5).8 Again, the arrangement of the hairwork portraits, with the mother and father at the top of the page and their children below, suggests a genealogical record, albeit an incomplete one.

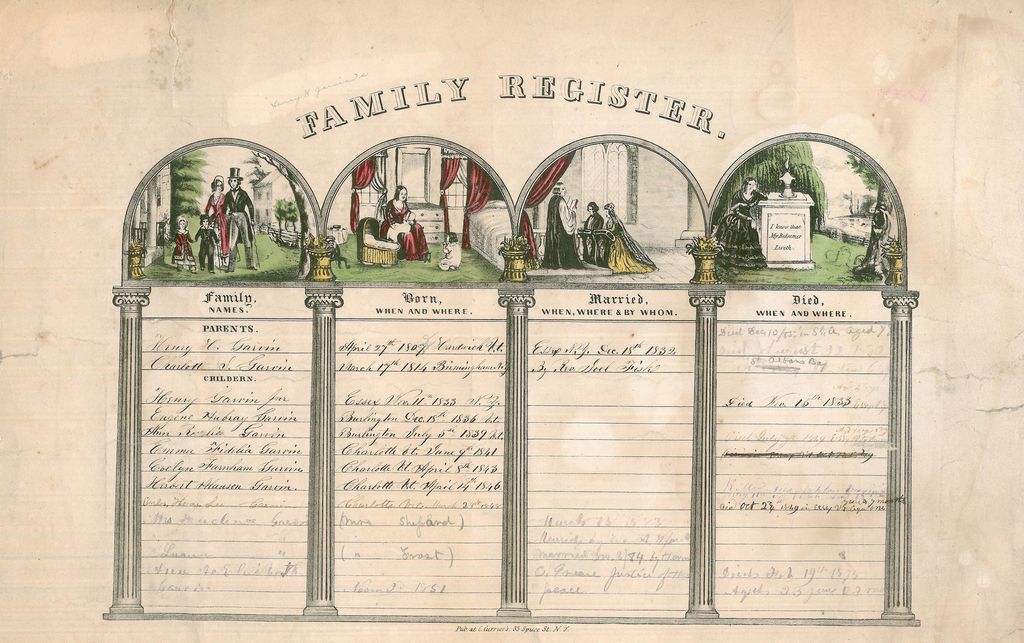

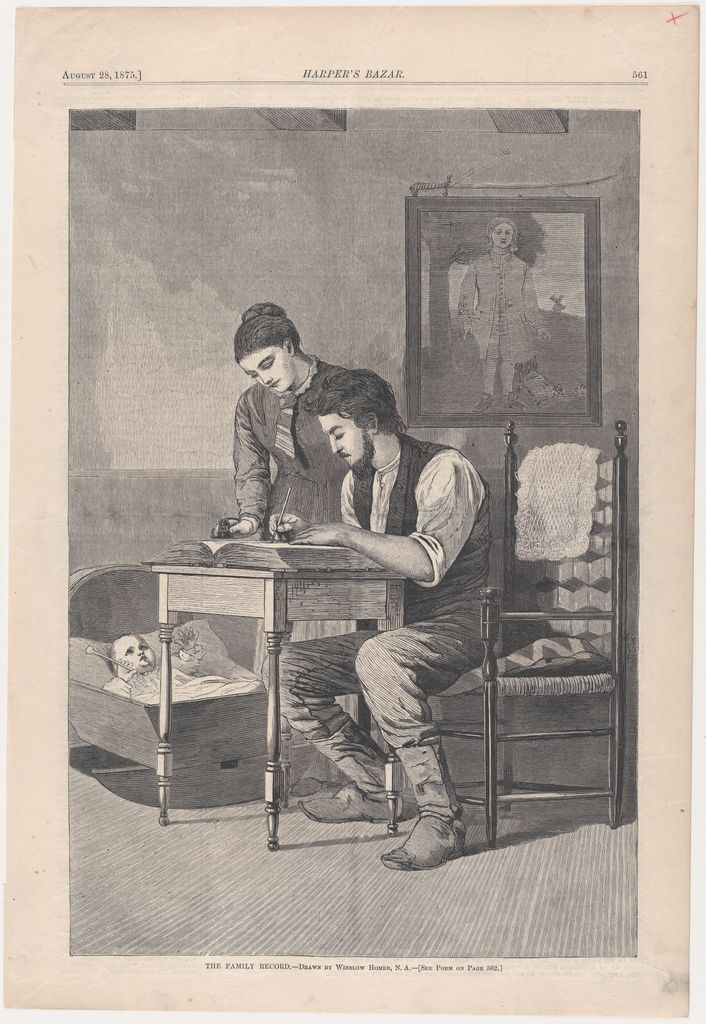

Another nineteenth-century Vermont family, the Garvins, recorded their members in a mass-produced family register showing the parents listed above the children (fig. 6). This lithograph includes illustrations of a typical white family: mother, father, son, and daughter. In one vignette, the dutiful mother tends to her children, and in another, she gazes at her husband, who does not look back at her. This imagery further demonstrates the patriarchal nature of genealogical practice, as described by Wulf. This patriarchal family record-keeping imagery appears in popular media too: an 1875 print after Winslow Homer from Harper’s Bazar shows a family in the act of writing down their history. The bearded white man records a new addition to the family lying in a cradle at his feet in a large book, his wife dutifully holding the ink pot steady as he makes his marks while the man’s ancestor watches from a painting above (fig. 7).9 Herein lies the tension that Grow’s album produces. Unlike the Garvin register or the Harper’s print, this woman does not just play a supporting role in providing or recording a family image. Grow is the maker of her album’s portraits, and the inscriber of her family’s names.

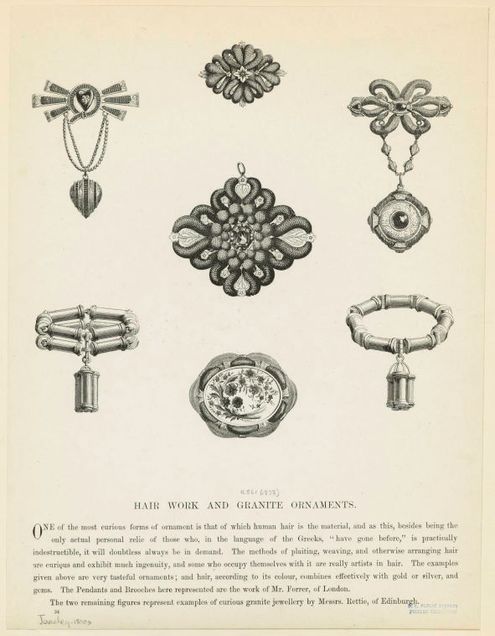

Most early professional hairwork makers were white, middle-class men trained as jewelers or metalworkers who fulfilled commissions to produce brooches, pocket watch chains, and other wearable articles (fig. 8).10 By the mid-nineteenth century, some women produced hairwork in their own homes, effectively cutting out the middleman to make objects directly from their family members’ hair. Interested crafters could reference a variety of texts, including Mark Campbell’s Self-instructor in the Art of Hair Work (1867) and articles in Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine. Campbell claims his book “will prove an indispensable adjunct to every lady’s toilet table.”11 Likewise, Godey’s assures “the fair reader” need not “be alarmed…I do not intend to frighten her with a long list of expensive machinery and tools.” Instead, she could use tools common in textile crafts, such as scissors and knitting needles.12 It is hard to know if Grow would have consulted sources like these, as the images in both of these texts look quite different from the objects she produced, and both were published decades after the initial date in her book. Still, these sources show how middle-class women learned this distinctly feminine-coded craft.

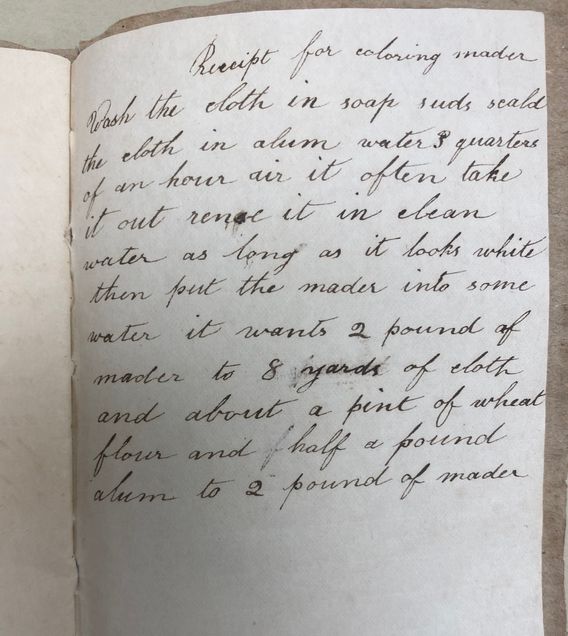

Grow would likely have seen her album’s connections to other domestic arts; she even included a recipe for madder root fabric dye, which could be used for textiles, in the back of her book (fig. 9). This further links her hair album with so-called “women’s work,” or those domestic crafts long undervalued in art criticism and scholarship.13 Grow was probably also intimately aware of hair as an expression of gender, which was integral to the nineteenth-century white woman’s image-fashioning, as evidenced in period advice guides.14 Domestic labor and hair were markers of feminine identity, and hairwork combined both of these forms of gender expression. Thus, it is even more noteworthy that Grow and other domestic hairworkers used the craft to depict not only themselves but also their female and male relatives. One wonders if the young artist saw irony in her use of hair, so often employed to display a woman’s status, to depict a brother or cousin instead.

Writing about salvage arts, feminist scholar Elaine Hedges argues, “in seeking to understand more fully the everyday lives of nineteenth-century women, we must piece together scraps as they once did.”16 The archive does not preserve the full story of Grow’s life, nor that of her family. The traces of the Grows I have managed to find are owed to the genealogical connections revealed in Lucy’s pages. She pieced together her family and community members’ hair in her books, and we can now learn about their lives through her work. As I have made clear, these were not neutral or entirely innocent practices: in creating these hair portraits, Grow promoted a family history that, while subversive in some ways, fit firmly within white, patriarchal systems. Albums like hers provide tremendous potential for further considerations of collaboration, women’s work, and the many other meanings woven into hairwork. As I have argued, they also expand our views of gender and family image-fashioning in the nineteenth-century United States.

____________________

Victoria Kenyon is a Curatorial Track doctoral student in the Department of Art History at the University of Delaware. Her research interests include the history of religion and the supernatural in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American art, and she is especially fond of exploring the macabre in visual and material culture.

____________________

1. The original date listed for this album in the Eberly Family Special Collections Library records was c. 1820, but the 1870 census record shows that Lucy (by that time married and with two children) was born in 1822. In the album, she notes her age is 17. U.S. Census Bureau, “1870 United States Federal Census,” National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, accessed through Ancestry, images reproduced by FamilySearch.

2. See Helen Sheumaker, Love Entwined: The Curious History of Hairwork in America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007).

3. Marcia Pointon, “‘Surrounded with Brilliants’: Miniature Portraits in Eighteenth-Century England,” The Art Bulletin 83, no. 1 (Mar. 2001): 61; Robin Jaffee Frank, Love and Loss: American Portrait and Mourning Miniatures (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), 13; Sheumaker, Love Entwined.

4. Karen Halttunen, Confidence Men and Painted Women: A Study of Middle-Class Culture in America, 1830-1870 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982), 58-60.

5. Heather Wolfe, “Where do Family Trees Come From?,” Folger Shakespeare Library, February 21, 2014. https://www.folger.edu/blogs/collation/where-do-family-trees-come-from/.

6. Karin Wulf, “Bible, King, and Common Law: Genealogical Literacies and Family History Practices in British America,” Early American Studies 10, no. 3 (Fall 2012): 482-86.

7. Emily Thornwell, The Lady’s Guide to Complete Etiquette in Manners, Dress and Conversation, in the Family, in Company, at the Pianoforte, the Tables, in the Street, and in Gentlemen’s Society. Also a Useful Instructor in Letter Writing, Toilet Preparations, Fancy Needlework, Millinery, Dressmaking, Care of Wardrobe, the Hair, Teeth, Hands, Lips, Complexion, Etc. (Madison, WI: T.T. Rustone, 1887), 33-36.

8. U.S. Census Bureau, “1860 United States Federal Census,” National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, accessed through Ancestry, images reproduced by FamilySearch.

9. Though outside the scope of my analysis here, Shawn Michelle Smith’s interrogation of racial family imagery is essential to my reading of this image: “‘Baby’s Picture is Always Treasured’: Eugenics and the Reproduction of Whiteness in the Family Photograph Album,” Yale Journal of Criticism 11, no. 1 (Spring 1998): 197-220.

10. Sheumaker, Love Entwined, 34-35.

11. Mark Campbell, Self-Instructor in the Art of Hair Work, Dressing Hair, Making Curls, Switches, Braids, and Hair Jewelry of Every Description: Compiled from Original Designs and the Latest Parisian Patterns (New York: M. Campbell, 1867), 6.

12. “The Art of Ornamental Hairwork,” Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine 58 (February-April, 1859): 153.

13. See Lucy Lippard, From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women’s Art (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1976).

14. Thornwell, Lady’s Guide to Complete Etiquette, 33-36.

15. Sheumaker, Love Entwined, 26.

16. Elaine Hedges, “The Nineteenth-Century Diarist and Her Quilts,” Feminist Studies 8, no. 2 (Summer 1982): 298.