Sensorium: Stories of Glass and Fragrance

Corning Museum of Glass

September 7, 2024–February 23, 2025

by R.J. Maupin

Museum visitors can spend countless hours looking at artwork on display, but other sensory experiences, such as smelling or touching, are largely forbidden. Despite these necessary protocols that protect material culture for future generations, curators can implement creative strategies to facilitate immersive, multisensory exhibitions. Sensorium: Stories of Glass and Fragrance, a 2024–2025 exhibition curated by Julie Bellemare at the Corning Museum of Glass (fig. 1), provides an expansive overview from antiquity to the present day of scent containers that held perfumes, scented waters, medicines, tobacco, spiced oils, and dried flowers. Given that these fragile glass bottles must be protected by vitrines for their safety, the exhibition runs the risk of prohibiting the visitor from engaging the very sense that structures its thematic narrative. Nevertheless, Bellemare cleverly addresses this challenge and offers an encouraging example of how curators can supersede the visual by inviting visitors to “think” with their noses.

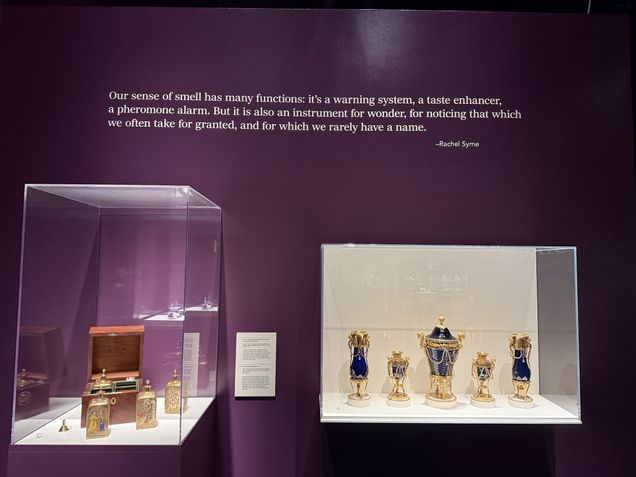

Outside of the main gallery is an introductory text and a small interactive station that reminds the viewer to imaginatively consider olfaction in tandem with vision (fig. 2). Under a wall text that asks, “What did money smell like in the 1700s?” viewers are prompted to consider the influence and violence of the European spice trade in Indonesia and Sri Lanka as they sniff spiced oils made from cinnamon, clove, nutmeg, and mace. This method of multisensory engagement seems almost obvious, given its popularity in other recent exhibitions, such as Five Senses of Chinatown at the Museum of Chinese in America and Our Senses: An Immersive Experience at the American Museum of Natural History. However, the danger of this strategy is turning experience into pure spectacle or eschewing a rigorous analysis of the objects. Since Sensorium’s smell station lies outside the main gallery and relates to a carefully selected set of scented oil bottles and potpourri vessels on the adjacent wall (fig. 3), it becomes a thoughtful, generative experience. While the visitor might yearn to smell other relevant materials, it would be challenging to make interactives for each of the works on display. Thus, it was a clever decision to use this station as an ode to a sensorial way of thinking rather than a central facet of the exhibition’s narrative.

After passing through this introductory section, viewers enter the main gallery, featuring deep purple walls and dramatic lighting that evokes the opulence of the colorful glass vessels within display cases. Three wall didactics chart the evolution of scent bottles, investigating histories of industrialization, luxury, and artistry. Cases in the center of the room diverge from the chronological displays, explaining distillation methods, religious uses, and the utilization of herbs and spices for medicine. This exhibition’s small space does not allow for a comprehensive show, but it does offer a diversity of topics, ranging from the attar industry in India, to the development of synthetic scents, to the nineteenth-century belief in the miasma theory. Viewers, then, can rely on their emotive memories of scent to easily find objects or narratives that spark personal intrigue.

Perhaps the most successful element of this exhibition, considering its institutional context in a renowned glass museum, is the exploration of the connections between scents and the materiality of glass. Physically, the impermeability of glass renders it an ideal container, but its fragility also reflects the preciousness of the expensive materials it is designed to hold. Some objects within the gallery require little contextualization to communicate this idea, such as a set of miniature glass bottles in a gold box, which depicts glassblowers crafting a vessel at a furnace (fig. 4). The maker’s decision to replicate this scene reveals how the box’s craftsman, glassmaker, perfumer, and consumer were consciously bound in an intimate relationship. While the visitor cannot physically handle this object, it is easy to imagine the original seventeenth-century owner touching it, picturing the complex methods used to produce the glass vials, and finding pleasure in its lavish aromas.

Beyond historical examples, Bellemare’s inclusion of contemporary glassmakers was a wise strategy to compel the viewer to consider smell as a primary way we interact with the material world. Glass artist Katherine Gray’s Paper, Sleeve, Wax, Block (2024) depicts four tools used to blow glass and small vials holding distilled scents of those that are emitted when using the tools in a hot shop (fig. 5). For example, the block is a wooden tool submerged in water that is used to gently shape the glass; as steam rises off the wood, it emits an unmistakable burnt odor. By capturing these smells, Gray refers to the nostalgia of her embodied experiences as a maker. Gray’s piece makes a powerful statement in this context, as visitors to the Corning Museum of Glass have the opportunity to see (and smell) a live demonstration of glass being blown or flameworked in nearby studios. In harmony with the exhibition’s title, Gray’s work—as well as many others that were selected for display—allude to the necessity of thinking beyond the visual and the meaningful stories we can tell when considering other forms of sensory stimuli in our everyday lives.

____________________

R.J. Maupin is a second-year master’s student in Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture at Bard Graduate Center. Her focus is American glass history of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries with particular interests in labor, industrialization, gender, and the performative aspects of craft.

____________________