Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

October 18, 2020–July 25, 2021

by Marina Wells

The sounds of Billie Holiday, Beastie Boys, and The Clash bumped pleasantly in the background of the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston’s exhibition Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, curated by Liz Munsell and Greg Tate. Though the exhibit centered on canonical artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988), the galleries also led visitors through the lives of lesser-known artists from various disciplines in the 1980s. The eight-gallery exhibition offered an atmosphere of collaboration, reflecting the era’s transformative projects of breaking down barriers, between New York’s streets and its white-walled galleries, between groups of people, and between the fine art, design, fashion, and music that they produced.

A Brooklyn-born, Black artist of Haitian and Puerto Rican descent, Basquiat became a pioneer in bringing graffiti and its allied arts into the mainstream. Despite being the canonized face of the so-called Hip-Hop Generation, Basquiat was hardly alone; the MFA’s Gund Gallery showcased works by his contemporaries, friends, and collaborators A-One, ERO, Fab 5 Freddy, Futura, Keith Haring, Kool Koor, LA2, Lady Pink, Lee Quiñones, Rammellzee, and Toxic, as well as other writers, filmmakers, and musicians with whom visitors may not have been familiar. They expanded the aesthetic world in which we imagine Basquiat living, while creating worlds of their own, including Rammellzee’s sharp Afrofuturism, Futura’s dance-like compositions, Lady Pink’s architectural spaces, and A-One’s self-proclaimed “aerosol expressionism.” On one wall played Blondie’s video for “Rapture” (1981), which features Basquiat DJing, graffiti artists at work, and Debbie Harry rhyming a verse in the first televised rap video. In a nearby display were pamphlets for legendary exhibitions that featured members of the post-graffiti art movement alongside such notables as David Byrne, Jenny Holzer, and Robert Mapplethorpe.

The galleries were like a party: They were textured, winding, music-filled, and even lit in places with black lights. Besides paintings, visitors encountered unexpected artifacts: a refrigerator, notebooks, clothing, turntables, ceramic plates, Corinthian columns, bejeweled watches, and one monstrous and wearable sculpture. The show satisfied a longing many of us share after an isolated year, as it brought diverse groups of people together, including figures both past and present.

Visitors were also met with interpretations from the museum’s Table of Voices program, where the curators’ discourse was complemented by poetry and prose from members of the Boston-area artist and activist communities. These interpretations offered further creative insight, while also contributing to the MFA’s efforts toward increased representation, diversity, and inclusion.

Writing the Future, of course, alluded in part to the unique ways post-graffiti artists invigorated their work with written language. From the roots of chunky tags like those of The Fabulous Five, Basquiat and others grew to use text liberally, on walls, on the page, and on canvas. They employed the art of text to layer meaning, cement trademarks, and write poetry. Collaborations with Holzer exemplified this relationship: Flashlight Text: Survival (1983–84) by Holzer and A-One reads, among a potpourri of spray-painted marks, “When someone beats you with a flashlight you make light shine in all directions,” (fig. 1).

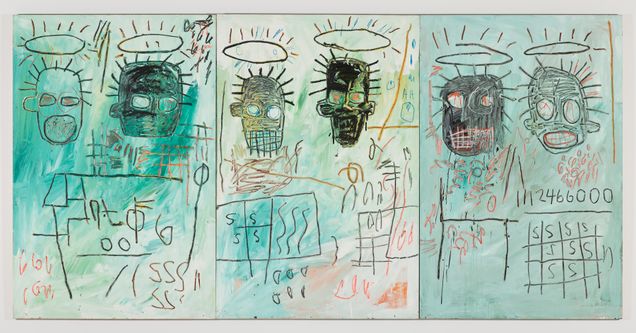

Writing the Future also gestured at the fact that New York in the 1980s was a site of myriad systemic issues. Basquiat’s Six Crimee (1982) depicts six heads with halos hovering above each one, perhaps an abstract reminder of Black innocence, racial profiling, and police violence (fig. 2). Like Six Crimee, the exhibition dignified Black figures and figures of color—even coronated them—but refused to explicitly express rage about contemporary circumstances. While the show highlighted Black and Latinx artists, it struggled to address the racism experienced by Basquiat and others in the predominantly white art world, and fell short of tackling pressing social issues, including police violence, drug addiction, or the AIDS crisis, which were contemporary with all of the artwork present. Yet, it thoroughly captured the excitement and possibility of change, something we should perhaps also aspire to celebrate in the present moment.

In thematic galleries about “Portraiture,” “Music,” and “Bodies,” the most profound stops were “Futurisms” and “Ascension,” galleries that highlighted the ways Black creators completely reshaped and reimagined Black futures. This was both figurative and literal: Beside the exit doors sat a mirrored pyramidal urn Rammellzee made for his own ashes, exhibited according to his request to be on view with his own work. The mirrors asked viewers to self-reflect and ask what remains they will leave behind, what the future is that they have written. Nearby, Rammellzee’s wearable performance suit Gash-o-Lear (1989) offered an example of otherworldly embodiment, of physically tearing down and reconstructing the limitations that seemingly guide our lives (fig. 3). Rammellzee, Basquiat, and others imparted a sense of moving beyond the current world as it stands, of finding liberation in making their mark. They suggested we can find hope in the titular act of Writing the Future, as dark and daunting as that process may be.

__________________

Marina Wells

Marina Wells is a PhD candidate in the American & New England Studies Program at Boston University. She holds a BA from Colby College in art history and literature, and has held positions at various institutions including in the Health Humanities at BU and at the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

__________________