New Landscapes: A Conversation with Drew Etienne

by Morgan J. Brittain

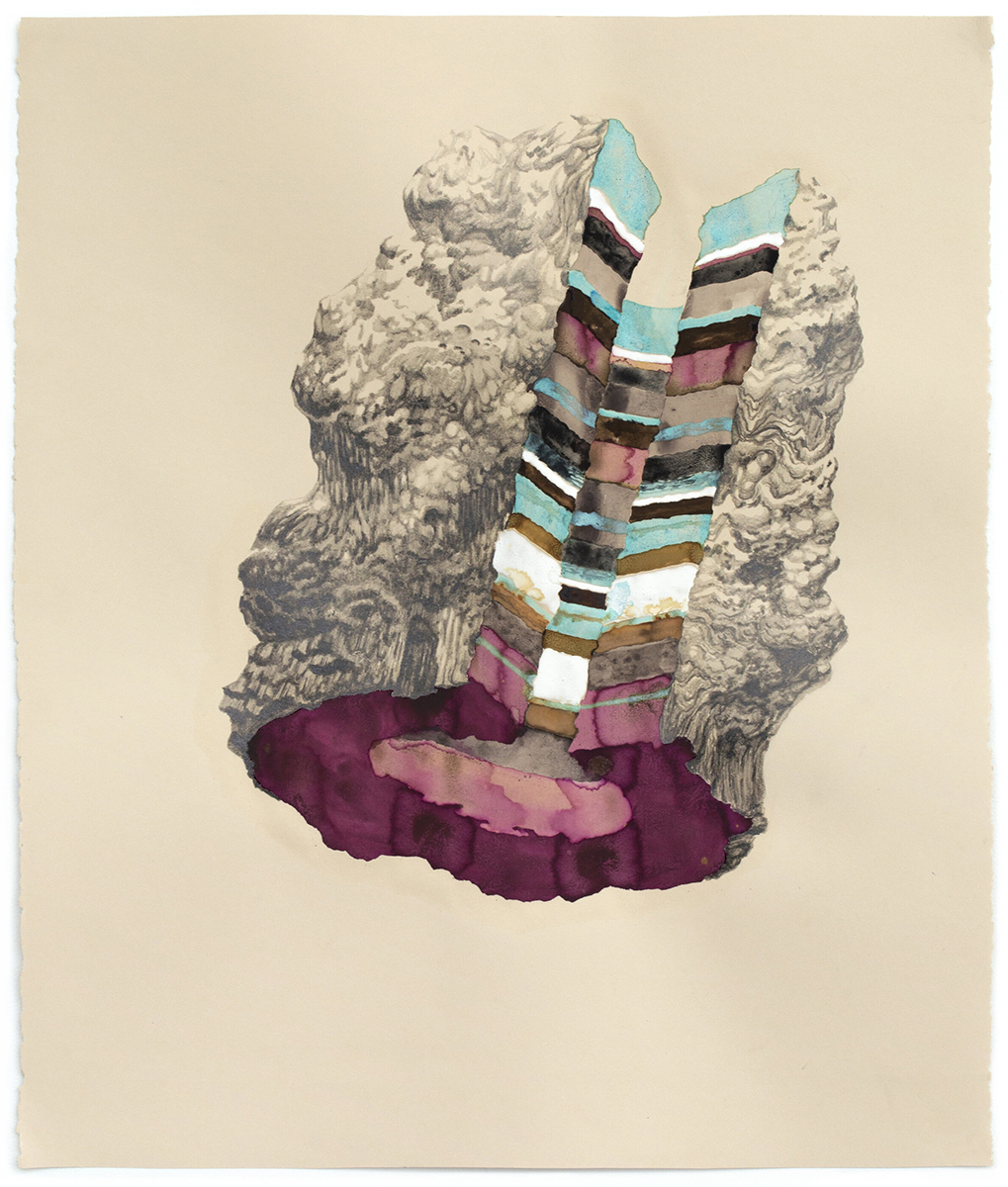

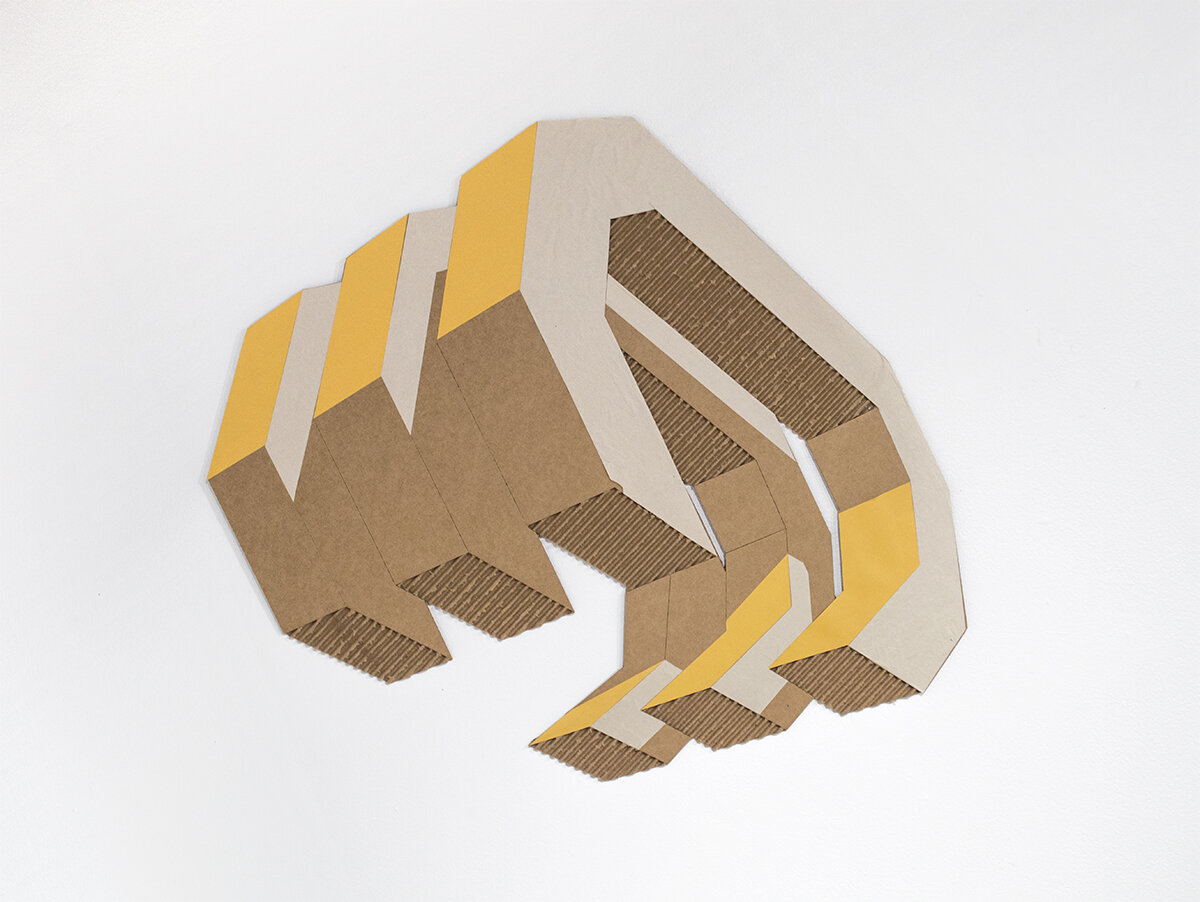

The multimedia work of Drew Etienne calls upon and reconstructs the Euro-American artistic traditions of portraiture, tondi, and landscape painting in order to confront corporate-caused environmental degradation and climate change. Etienne’s “new landscapes,” some of which were featured in his solo show The Technosphere at the University of Iowa in spring 2020, transport viewers to an imagined, temporally distant earth on which human existence can no longer flourish and is, in fact, long absent.1 In place of life are only extractive machines, succeeding the tools of today’s increasingly deregulated capitalist industries. The Collector (2020) is there to gather the residues of human activity: plastics and other petrochemicals transformed by geological processes into new kinds of stone (fig. 4). Depicted in Etienne’s painting New Lithosphere (2020), a conscious appropriation of Thomas Moran’s Cliffs of the Upper Colorado, Wyoming Territory (1882), and given three-dimensional form in his Anthrostrata (2020), these composites are evocative of a real geological phenomenon called the plastiglomerate: fragments of natural sediments and plastic molded into stone through time and pressure (figs. 1, 6).2

Etienne translates ideas of resource gathering into “a collaboration with the environment” through his artistic process—a process involving the collection and transformation of discarded, found, and foraged materials into artwork. Having used repurposed media in The Technosphere, Etienne’s most recent work incorporates inks made from naturally occurring reactions and plants (figs. 2, 3, 8). This reflexive mode of making resists the instincts of a deregulated corporate capitalism to conquer, extract, consume, and dispose. Whereas portraiture and landscape painting of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were deployed in justifying white-settler claims to Indigenous lands and US expansionism, Etienne’s signature “twist[s]” on these traditional formats oppose such colonial functions. In this interview, Etienne and I discuss The Technosphere, developments in his process, his turn to using natural materials, and his current work.

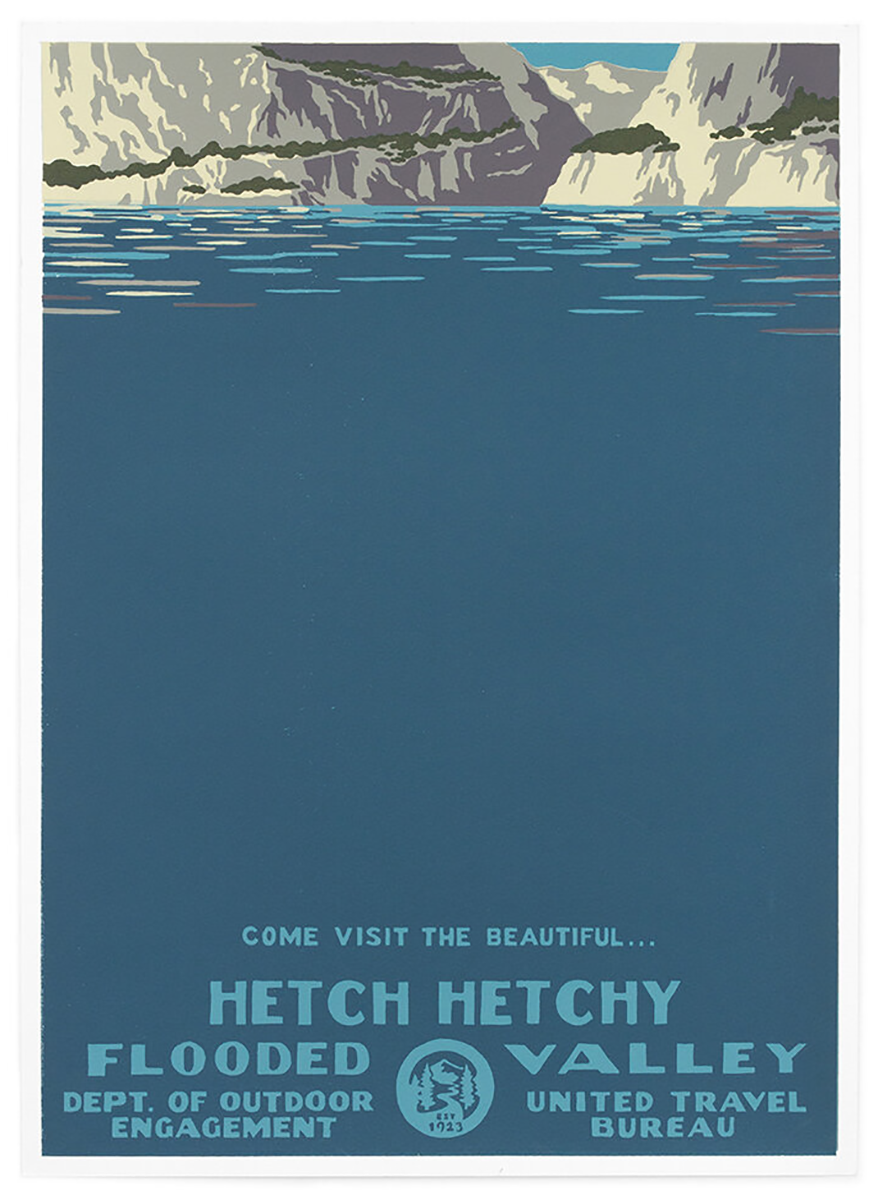

Figure 1: Anthrostrata (2020). Salvaged extruded polystyrene foam, expanded polystyrene foam, cardboard, tempered hardboard, and upholstery foam. Figure 2: Specimen 001200920, n.(sancorshel) (2020). Graphite with inks made from foraged pokeberries, goldenrod, walnut, acorns, chalk, charcoal, oak galls, salvaged steel, and copper on paper. 26 x 22 in. Figure 3: Untitled (2021). Inks made from foraged goldenrod and salvaged copper on salvaged wood. Diameter 7 in. Figure 4: The Collector (2020). Salvaged extruded polystyrene foam, expanded polystyrene foam, cardboard. 36 x 60 x 96 in. Figure 5: Portrait of the Collector Mk (2020). Repurposed cardboard, paper. 23 3/4 × 27 1/2 in. Figure 6: New Lithosphere (2020). Oil and acrylic on canvas and repurposed wood. 60 x 84 in. Figure 7: The Technosphere, (2020). Oil and acrylic on canvas and repurposed wood. Diameter 48 in. Figure 8: Untitled (2021). Inks made from foraged goldenrod, walnut, and salvaged copper on salvaged wood. Diameter 5 3/4 in. Figure 9: Hetch Hetchy (2019). Six-layer serigraph. Edition of eighteen, self-printed. 18 3/4 x 13 3/4 in. All images courtesy the artist.

Interview Transcript:

Morgan J. Brittain: I hope you could start by talking about your use of materials, both about your thinking behind it and how the kinds of materials you’re using has evolved, as well as the processes you use to gather materials and then ultimately transform them into artwork. There are really a number of things at play here; you have those Anthrostrata sculptures from The Technosphere show in spring 2020, and those graphite and ink Specimens (2020) from an even more recent series, which seemed to evoke the real contemporary phenomenon of plastiglomerates. There’s also both The Collector sculpture and portrait from The Technosphere show with a claw-like form that’s so evocative of extractive industry but also of the human hand in the act of gathering or foraging. So could you discuss your process, particularly how you collect and use materials, the tensions between this process and industry, and how you think about your responsibilities as an artist?

Drew Etienne: I’ve actually been collecting materials for longer than I knew what I wanted to do with them. I think it started with just taking a look at what kind of waste I was creating, whether it’s just saving packaging materials from things that I would order online. It had been in the back of my mind for a long time. I took this class with Isabel Barbuzza at the University of Iowa called Art at the Edge of the Landfill, and I took it because I kept almost hoarding these materials and getting materials from other artists at the school and things like that, just constantly collecting materials. But I didn’t really know what to do with them. I didn’t have a lot of experience with sculptural stuff, and this was a sculptural class that I’m referring to.

That was a big turning point for me. Because of that class I heard about Edward Burtynsky’s Anthropocene documentary and that was also a big influence in this kind of turning point where I started to get ideas about how I could utilize these materials and make use of the waste that I was making but also things that I would collect around the art building.3 Once I got an idea of the show The Technosphere then I started collecting things more in earnest, literally just going to dumpsters. I would always check the dumpsters by the art building [. . .]. I would go to other places [. . .], if I saw someone doing demolition somewhere I would check the dumpsters.

More recently for the show that I’m doing right now [. . .], last summer, they were demolishing some mobile homes near where I live, and there’s all this pink insulation foam. And I just asked [the demolition worker], “Is this stuff going to get thrown away?” He’s like, “Yeah.” I was like, “I will take all of it.” So it’s just been a matter of dealing with storing it and things like that, but that whole thing started with the show that I did in the spring called The Technosphere. You mentioned the Anthrostrata. I’m actually not sure if I completely remember the flashpoint for that but I do remember taking some of those materials home over Christmas break and just working with them in my parent’s garage, cutting things up and seeing what I could make, and I got this idea of these small sculptures that can serve as miniature landscapes of the future but also can appear on a smaller scale. You mentioned plastiglomerates; it’s that same kind of idea, or like a technofossil: this geological specimen from this future world where the physicality of the landscape has changed so much because of what we’ve done to it. That was a big moment. The funny thing about those Anthrostrata for me is I was working on them, and I worked on them by myself for a while over winter break, and I had no idea whether they were something that other people would think are really cool or whether it was the silliest thing that I’ve ever done. I was really in a mode of playing with these materials and just following my gut, and thankfully people responded really well to them. I think one of the things that I found really satisfying with those by the end was that they were calling to this kind of future of post-human or post-life world that I was depicting in The Technosphere through the subject matter of the landscape, but also very directly through the materiality [. . .], making these sculptures out of the same sorts of things that are ending up in the strata of the Earth and in these plastiglomerates, like you say.

You also mentioned the claw-like form. I don’t think that I’ve actually thought about it in relation to the foraging or the gathering, but I like that idea. You do mention that it’s evocative of the extractive industry, and that’s interesting, too. When I was designing those I was actually using a program called SketchUp, which is just a really easy way to design things—design three-dimensional forms. I was just trying out these different forms, and, going on instinct, I would know when I found the right form. I didn’t totally know right away why it felt right until looking at it a little bit later and seeing how much in some of those forms there was a common thread of this grabbing motion, extractive thing, this action of taking. That was the main idea behind that. But I do like how that ties in with the foraging; it’s the same act, it’s just a different philosophy behind it. The foraging that I’ve been doing lately as far as the salvaged materials and also materials that I’ve been using to make inks [. . .], that has to do with more of a collaboration with the environment versus a conquering of the environment, which is where the extractive industry, and colonialism and capitalism in general, tends to take things.

My responsibilities as an artist [. . .], I think that one artist, doing their best to think about the sustainability of their own practice, is obviously not going to change everything or be the flashpoint that turns everything around, but I am hopeful that the behavioral changes that I’ve made in my practice are something that can influence people outwardly. I know that that can happen because I’ve made changes in my own life, even outside of my art practice, as a human. I’ve been influenced from other people or things that I’ve heard from other people or seen other people do, so I think that using any amount of a platform that I might have as an artist, and showing these kinds of ways of thinking about how you can improve the sustainability of your behaviors, is important. I think it’s important in creating as large of a voting bloc that understands how important this stuff is because that’s the only way that we can change the behaviors of the people who are really doing the worst work or are having the worst impact: the large corporations who are taking advantage of whatever lack of regulation there is in our capitalist system to exploit other people and gain their capital.

Last fall I started researching more about how to create my own inks. Originally I was trying to create inks to use with the Japanese woodblock printmaking techniques, and I’m still working on that, but in the process I learned a lot about just what kinds of things can be used to make ink. I made some inks that I used in some drawings in this small show that I did last fall called Evidential Existence.4 I had a lot of success in creating things that were really usable but also new materials that I had to collaborate with because they wanted to do their own thing. It was a really rich process of exploration, both in the actual foraging for the materials, experimenting with the creation, and then experimenting with actually implementing them, so it was really productive.

I learned about a lot of natural materials that you can use [. . .], so things that are really abundant and things that have been used for a long time. Black walnut is really abundant here in Iowa City; goldenrod, which is a weed that grows everywhere [. . .], it’s like on the side of every road; pokeweed, which gives a really strong pink and purple tone. And again, it’s just a weed and you’re basically just harvesting the berries and smashing them up. That’s one where you want to be careful if you do it at home because it is toxic; you don’t want to ingest those. I’ve also recently started harvesting rust off of metal, steel that gets left over, that I pick up maybe from the printmaking department. They use it in their etching. And also, copper, I was able to make copper oxide just with vinegar and salt and copper and a little bit of waiting.

The interesting thing is, I’ve most recently been using those in these small tondi or tondos that are portraits of future worlds or other worlds. But, anyway, I’m using these inks together and they’re creating these reactions that I never would have had otherwise. They’re reacting to each other and creating these almost miniature landscapes in a way.

I guess the reason that I started getting into that was, I think, honestly, it was a little bit of one-person protest, or an attempt at circumventing capitalism in a small way [. . .], like a little protest, thinking about how resourceful I could be finding and creating this stuff myself instead of buying whatever materials that are reliant on mining or exploiting the landscape in some other country, and then shipping the materials and then going through whatever industrial processes are necessary to convert the materials and then shipping them again to my house. I was thinking about what I could do to have a much smaller footprint and that became me just walking around Iowa City and collecting these things and not really needing to do too much as far as what was necessary to convert them into something usable.

Along the way—and this was something that was noted by one of my professors at the University of Iowa—I ended up in a much slower mode of working in a good way [. . .] and I think this is also something that came about from the pandemic. I think a lot of people have been recently rethinking how important productivity is and thinking about productivity and how it relates to our feelings of self-worth. I ended up in this much slower mode of just [. . .], I get to go outside and go on a walk and get out of the house and search for these materials, and it’s something that felt very healthy physically and mentally. It was very rewarding to be able to find these things and turn them into something that I could actually use myself. It’s so crazy that that’s something that’s so foreign in my life and other people’s lives right now [. . .], this idea of going out and finding something and making something out of it, as opposed to just ordering it on Amazon or whatever, because that’s how, obviously, how much our way of life has shifted post-industrialization and in this capitalist system. It’s just interesting [. . .], it’s not something that’s foreign to humanity, but it’s certainly foreign to how we’ve been living in Western society for a while, so that’s an interesting change.

MB: The theme of this issue of SEQUITUR, as you know, is “Deregulation.” That theme is, of course, at play in these worlds you create in which petrochemical corporations have gone so unregulated that not only can human life not survive but ecosystems are too disrupted for plant and animal life to continue. That’s true in the ways you adapt Thomas Moran’s Cliffs of the Upper Colorado River, Wyoming Territory for your painting New Lithosphere. In that Moran painting, as in so many landscape paintings of the nineteenth century, the figures representing Indigenous people, presumably meant to be Shoshone people based on the geography, are relegated to one small area of the canvas while landforms are the vast majority of the composition. As you know, one of the ways I’ve interpreted your work is as “new landscapes.” In reality though, that’s an oversimplification because you’re really in conversation with multiple Euro-American and European traditions, including portraiture and, through the title work of The Technosphere show and very recent work, tondi as well. But in each case you divert from the subject matter and often the media that would be traditional. In essence, you shirk what the de facto regulations of the genres have been. I hope you can talk about that, and I’m wondering what kind of work you see this is doing, whether it’s decolonial or something else.

DE: I do see a relation to this idea of decoloniality in the sense that one of the main philosophies in my work is always shedding this idea, which I think is a very Western idea, of humans conquering and controlling the environment. I think that’s one of the most harmful ideas that we’ve stuck with over the years. We certainly haven’t gotten over it. You know, obviously European colonists came to take resources they needed for building ships or whatever. The whole ethos was going elsewhere to conquer “the other,” whether that’s other people, territories, lands, and other conscious beings [. . .], meaning other animals as well. I think that’s one of the through lines in my work is that I want humans to be able to [. . .]. This is not new either [. . .], these sorts of ideas have been talked about since at least the sixties and seventies, the ideas that we are a part of a larger ecosystem and we are not the lords of the Earth. We should view ourselves as the stewards of the Earth. I think a lot of that comes from this confidence of, “humans are so much smarter than other animals” or whatever; we do have a very complex intelligence, and we do have the ability to imagine alternate futures which maybe other animals can’t do. I think we also have an inherent responsibility to view ourselves as stewards of the Earth, but I think we really need to shed the idea of conquering—that’s the central thing with colonialism, capitalism, extraction, industrialization. It’s all about using whatever for human benefit as opposed to trying to live in conjunction with the natural processes of our environment.

You mentioned the new landscapes and Moran’s Cliffs of the Upper Colorado River. That painting was like a flashpoint for me, for whatever reason, when I was looking at it. One of the things that I have done in multiple ways now is using a convention, as you mentioned, like the sort of traditional methods or genres and mediums and adding a twist to them to talk about something that’s going on now, or getting people to rethink our history and think about the future. So, I think that my painting New Lithosphere and how it relates to that painting by Thomas Moran is using that format of the romantic painting or the sublime and envisioning an alternate future.

I haven’t really talked about the “loomers” in this conversation, but they are these entities that I imagine in this far distant future, far distant post-life future that are in this scenario because, wherever they come from—I think it’s interpretable, whether they’re something that has to do with AI or whatever that comes out of Earth or whether it’s visitors from elsewhere, it’s not really necessarily that important—I think that they serve as these kind of future specters of the effect of capitalism, necrocapitalism, the idea of creating a debt of death that you can never repay. It’s hit a pinnacle, everyone has gone, and all the history of humanity, all of the waste has over time, and through pressure and time, created this new landscape which maybe has new resources. When I was originally envisioning that show and thinking about the kind of correlations to colonialism, the idea of this sort of grabbing hand and the idea of these entities coming in to take resources [. . .]. I was thinking, there was more of a parallel there. It’s a reflection of the same kind of story of colonialism, but really it’s just the continuation of the same story, right? It’s colonialism, capitalism, paving the way for these specters of the future to have these new resources that they can collect.

As far as using conventional formats and putting that sort of twist on it [. . .], I did that with a couple of the paintings in The Technosphere. I’ve done that before with some WPA-style posters that I’ve made. They’re highlighting [. . .], they’re using the exact same iconic format, but they’re highlighting landscapes that have been altered or ruined by human industry. I think that is a really effective way to get people’s attention, but then also to get them thinking about why we pick the certain places that we pick to protect and why we pick the certain places we pick to destroy or extract resources.

The tondi that I’m working on right now are [. . .], I think you also mentioned [. . .], like portraiture a little bit. There is some history of portraiture in the tondi, I think. I also had a couple pieces in The Technosphere show that were called like Portrait of the Excavator (2020), Portrait of the Surveyor (2020), and The Collector (2020), which are these “loomers.” At the time I was thinking, it’s kind of like seeing the portrait of the colonial settler, the white male colonial settler, in front of his land, his house, his property. But with the tondi, they really are serving as portraits. And this again has to do with the work that I’m doing right now for my show. They’re kind of tragic portraits of either [. . .] and this is again something that’s a little bit interpretable [. . .], other worlds or exo-civilizations who have gone through a similar process of not being able to survive the behaviors that they’re doing as a civilization, or also just alternate futures of possible futures of the Earth.

I don’t know. There’s something [. . .], I keep going back to that as well [. . .], there’s something for me about just tweaking those formats a little bit. I think it’s a way of getting people’s attention and just getting to think a little bit differently about these things that I’m bringing up as far as the really important contemporary issues that we’re facing.

MB: I think the tondi are so interesting because one of the things I was taught about tondi in the Italian Renaissance is that it’s very much linked to birth, so this round format comes out of food trays that were given to new mothers as they were recovering. And also it was commonly associated with Mary and Christ, that sort of religious imagery [. . .], but this idea of birth and your use of that format as being this rebirth of Earth as something new but also at the same time the death of Earth as we’ve known it.

DE: Right. I really like that read. I think that’s another really important thing that’s been a through line of my graduate work. There have been many, many faces of Earth over the 4.7 billion years it’s been around. Whether it was cyanobacteria covering the Earth, dinosaurs being the dominant species, it’s gone through a lot of changes and it can go through a lot more changes. I do like that association with the tondi and rebirth. I always like hearing your interpretations. There are a lot of different phases in the process of doing something [. . .] because I’m following my gut and then starting to understand why it needed to be that way later versus having a very specific idea that I want to talk about, and then just figuring out how to go about expressing that through visual means. But, either way, it’s inevitable that someone will see something that I didn’t and view it in a different way. I think it’s always really enriching to think about that.

____________________

Morgan J. Brittain

Morgan J. Brittain is a PhD student in American studies at William & Mary. He received his MA in art history from the University of Iowa in 2020. His research takes an ecocritical approach to historic and contemporary landscape traditions. His work has also been supported by a Newberry Library Consortium Grant and the Gilcrease Museum’s Helmerich Center for American Research.

Drew Etienne

Drew Etienne is an MFA candidate at the University of Iowa where he has been employing painting, printmaking, and sculptural modes of working. The goal of his art is to shift the viewer’s focus away from the anthropocentric toward the micro- and macroscopic to aid in understanding scales of space and time that are not innately understood, as well as the effect of human behavior on ecosystems past, present, and future.

____________________

Footnotes

[1] Maxwell Hearn, “New Landscapes,” in Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013), 73–137. Hearn uses “New Landscapes” to describe the reinterpretation of Chinese landscape painting traditions by contemporary Chinese artists.

[2] See Amanda Boetzkes, Plastic Capitalism: Contemporary Art and the Drive to Waste (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019).

[3] Anthropocene: The Human Epoch (2018) is a documentary film by Edward Burtynsky, Jennifer Baichwal, and Nicholas de Pencier that follows a group of scientists who are examining the devastating effects of human domination on planetary ecology, particularly since the mid-twentieth century.

[4] Evidential Existence was held in fall 2020 on the Second Floor Gallery of the University of Iowa’s Visual Arts Building.