Memories and Connections: Remote Field Study of a Bodhisattva Hall in Sannohe, Aomori, Japan

by Mew Lingjun Jiang

This report focuses on a single Kannon zushi (観音厨子 or a portable shrine dedicated to a bodhisattva) decorated with karuta (from the Portuguese carta, or patterned playing cards). This piece is located at Nose Kannon Hall (野瀬観音堂 Nose Kannon-dō) in Sannohe, Aomori, Japan (figs. 1-a and 1-b). The study, done remotely through online meetings and interviews with Sannohe locals, sought to preserve memories of this particular place during the challenging COVID-19 pandemic.1 Through the process, I gathered documents and images for my in-progress project to trace the history of Buddhist-Shinto integration and the use of karuta images in religious practices in Sannohe.

The zushi at the hall is perhaps the only known piece in Japan covered with karuta. This decorative approach creates a visually compelling pattern of unique abstract designs and strong black-red contrast (fig. 1-a). In addition to the zushi’s appearance, the enshrined Shinto and Buddhist deities also make the hall a curious place. While the hall enshrines a “True Bodhisattva” (聖観音 Shō-Kannon) wooden sculpture, the zushi conceals a bronze plate with a relief image of a “hanging buddha” (懸け仏 kakebotoke) as “The Deity of Gambling” (賭け事の神様 Kakegoto no kamisama) (fig. 1-b and fig. 2 ).2 The connection between the kakebotoke Buddhist icon and the Deity of Gambling is made through a pun: “to hang” (懸ける kakeru) sounds like the word “to gamble” (賭ける kakeru). 3 Although the origin of the Deity is unclear, the belief in “The Great Deity of Karuta” (カルタ大明神 karuta daimyōjin) as a playful wish of karuta players has been portrayed in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century popular fiction, with abstract karuta figures reinterpreted beyond the gaming context.4

The decorated karuta, which might demonstrate karuta players’ devotion to the deity, are carefully nailed onto the zushi to cover its surface, forming unique visual patterns in black and red using the four highly simplified suit markers of batons, swords, cups, and coins.5 Cards on the front were arranged into four magic-square groups: in the squares, the pip numbers in any of the outer horizontal and vertical lines add up to 15, while any horizontal, vertical, or diagonal line crossing the center has a sum of 25 due to the special layout (see figs. 3-a and 3-b).

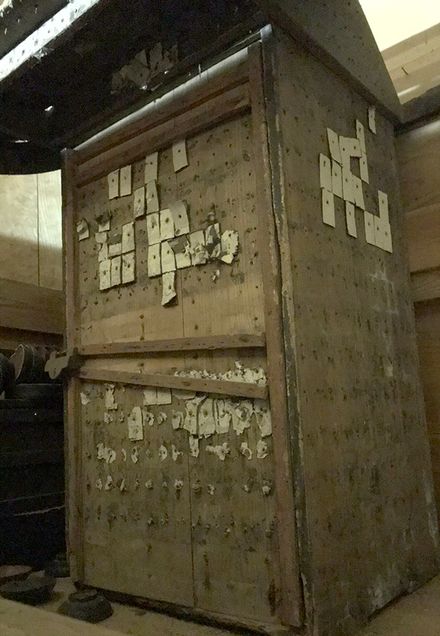

The cards are “kurofuda” (黒札), a kind of regional bold-patterned karuta, developed and used in Northeastern Japan in the late nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries, and derived from the illustrated Portuguese-patterned four-suit playing cards introduced by European merchants in the late sixteenth century. To accelerate the printing process to meet the demand created by popular card games, karuta design became abstract and simplified. The meanings of karuta figures were reassigned by local players, who used new rules and names in their games. Karuta, like the ones decorating the zushi, even developed new functions as religious items. However, because the current zushi was rebuilt after a fire in the 1930s, it is unknown when the devotion to the Deity of Gambling started in Sannohe, or whether these cards represent the same type of karuta used at that time. The old zushi survived and is still stored in the hall, with a few cards remaining on its surfaces, and its history requires further investigation. (fig. 4).6

Since 1617, Nose Kannon Hall has been managed by the Kudō family and used for religious events which display the usually-concealed kakebotoke.7 Visitors today still offer card decks to the deity for luck in games and lotteries.8 Although Nose Kannon Hall occupies a distant location on a mountain, hours away from the nearest town, the decennial public opening attracts worshippers and visitors curious about karuta and traditional games. Articles as well as videos uploaded by visitors attracted more viewers online and called attention to the intriguing appearance of the zushi and the religious traditions in Sannohe.

The public opening scheduled for this year has been postponed to August 2021, when I plan to visit the site to conduct an actual field study to obtain more information and images of Nose Kannon Hall. With this project, I hope to call attention to religious traditions developed by local communities outside major areas and to form a more comprehensive history of the change in karuta designs and usage beyond games and gambling. As long as these places and stories are remembered, they will continue as a part of the shared memory of the local community and of our humanity.

____________________

Mew Lingjun Jiang

Mew Lingjun Jiang studies Japanese art history focusing on prints and ephemera. This current project looks into the reinterpretation of signs and meaning-making of images in karuta. Handling them is like holding a time-travel pass. Some colleagues joked that it was the Great Deity of Karuta that guided Mew here.

____________________

Footnotes

1. This field report was an outcome of online collaborations with traditional game collectors, researchers, and linguists in Japan. Initially, I planned to visit Nose with other researchers in summer 2020, but due to travel restrictions under the pandemic, we had to cancel the plan. Instead, the study resumed as a remote project connecting people from different regions. I am indebted to those who met with me online: Takashi Ebashi, Yuka Hayashi and her colleagues from the National Institute of Japanese Language and Linguistics, Takuma Itō, Mariko Iwasaki, Hiroyasu Kudō, Yuka Morikawa, Hironori Takahashi, and Nobuaki Takerube. Special thanks to Sannohe Town, Sannohe Board of Education, and Aomori Prefecture Library for providing contacts and documents. And special thanks to Mariko Iwasaki for kindly sharing her interview and photographs. Thanks to Or Porath and Fabio Rambelli for encouraging me to reach out to the locals as the first step of this study.

2. The Shō Kannon, or Noble/True Kannon is one of the Six Kannon Bodhisattvas in Japanese Buddhism. Its icon is presented as idealized and humanlike and is “the most commonly represented manifestation of Kannon.” See Sherry D. Fowler, Accounts and Images of Six Kannon in Japan (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press, 2016), 17–8; The kakebotoke “hanging buddha,” also called mishōtai 御正体, is a tradition since the medieval age to indicate the identity of the Shinto kami deity and to present the kami’s body in a materialized form, influenced by Buddhist iconography. The current enshrined kakebotoke bronze plate relief in Nose Kannon Hall was made in the 1930s after a fire, while the old plate is still stored inside the shrine. Interview by Iwasaki Mariko and Noda Takashi with Nose Kannon Hall superintendent Kudō Hiroyasu in Sannohe, Aomori, September 6, 2020.

3. An observation by Takuma Itō.

4. For instance, the deity of karuta has been portrayed in Ihara Saikaku 井原西鶴, “A Man Coming to Ponto (Ponto ni oite kita otoko 先斗に置いてきた男)” in Twenty Undutiful Stories in Japan [Honchō nijyū fu kō 本町二十不孝], 1686, and Saikaku, “The Deity of Karuta that Does Not Fulfill One’s Wish (Inoredo kikanu karuta daimyōjin no koto 祈れど聴かぬ骨牌大明神の事)” in The Portable Inkstone [Futokoro suzuri 懐硯], 1687; the spirit of karuta in Santo Kyōden 山東京伝, Ohana and Hanshichi’s Buddhist Benefits and Card Games [Ohana Hanshichi kaichō riyaku mekuriai お花半七開帳利益札遊合], 1778, and the personification of karuta in Kyōden, An Unavailing Allegory of Karuta [Hyakumon nishu mudakaruta 百文二朱寓骨牌], 1787.

5. Cards were allegedly devoted and placed by visitors coming from Towada (in Aomori, north to Sannohe), interview, September 6, 2020.

6. Sannohe-machi Kyōiku-iinkai 三戸町教育委員会, “Nose Kannon Gaiyō” 野瀬観音概要, manuscript, received April 30, 2020, and interview, September 6, 2020.

7. The public opening used to happen every sixty years, then every thirty years, and now every ten years. According to Kudō, this change was to bring in more visitors to view the public opening: if the public opening happened only every sixty years, one visitor would only have one chance in their life to view the Bodhisattva icon, Sannohe chōshi chūkan, 264, and interview, September 6, 2020.

8. Reported by Nobuaki Takerube, who visited Nose in the 2000s, and interview, September 6, 2020.