Seeing Invisible Mxn

by Kristina Bivona

Section One

The Crusher

I went to the exhibition alone, as I usually do. I had to wiggle my way through a gallery filled with work I really wanted to care about but hardly could. See, I am deeply informed by my time as a sex worker and smothering my way through higher education.1 This experience colors the lens through which I view art. For years, the kinky requests of privileged men gave way to my agency through pay and self-exploration. I regurgitated food onto erections and zapped testicles with cattle prods for a livelihood. That money kept me alive and educated. The upward mobility from sex work to the Ivy League allows me to write from my advantage today. I humored egos in sex and witness that similar function in art. I found my first stabilities in myself and in the world this way.

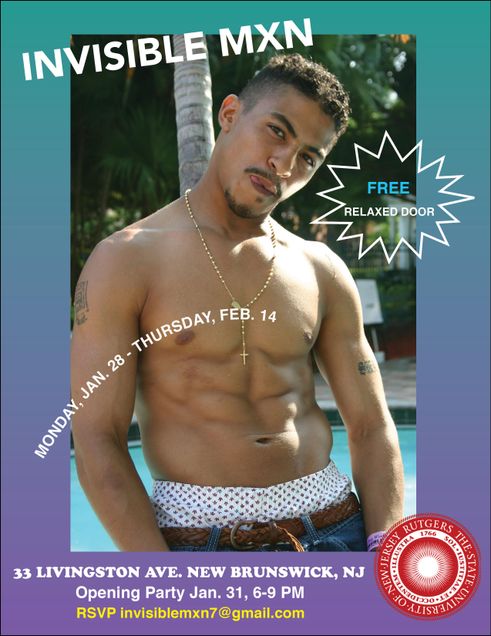

The invitation for Invisible Mxn implied a repositioning of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man with the queer lens of East Coast underground sex (fig. 1).2 The last line disclaimed, “Unlike other parties of our nature, CELLPHONES & WATCH LIGHTS ARE ALLOWED but we urge you to consider the consensual photography of others.”3 I found my place between art, sex, and the underground when I went to see Invisible Mxn by Malcolm Peacock that night. So, I wound around the gallery past a massive zoetrope and saw paintings with too much green.

What caught my eye in the short journey around the gallery were the gestures and looks from potential johns in that academic space.4 I noticed men viewing the formal works of art whose posture and wandering eye crept up from behind privilege and confidence. Often, I can catch that glance zipping out from that soft place in between where power, denial, and insecurity thrive. I notice the ways men wield their vulnerability and see it as it moves the gaze from desire to pay. I am not above that line. I too dream of things I do not control. I let my sight drift to thoughts of at least five johns enjoying the comfortable works around the crowded gallery, folks who could detach enough from their human connection and their sexual prowess so that only a professional can suss out satisfaction. I am that ho.

Finally, tucked toward the back and almost intentionally quarantined off, I entered Invisible Mxn, a multi-room installation by Malcolm Peacock. I was greeted with a notorious hand towel. While I was unsure about the intended use for this towel I drew on experience to define what it meant for me. This was the cum towel. The one given to me that day was neat and clean but not new. Still, these little terrycloth squares were unlike the self-laundered dungeon towels of my history, which always kept their musk.

This distribution was crucial. It denoted that the viewer was walking into an establishment of sex despite the connotation of an art show established within the confines of an institution of higher education. The immediate reference to a sexual establishment filtered through my experience as an artist, student, and lapsed sex worker.

I finally felt like I was meant to be somewhere in an art space, somewhere my sensibilities about art, engagement, sex, and viewership aligned. I also identified that this space was not catered for me (a short white lady with a well-refined badditude) though my place as an outsider was open and gracious. Upon entry into this staged sex club I could reflect on how spectators and participants may view consent in institutions and underground spaces. This charged my reception of Invisible Mxn with fortitude and candor. I felt safe.

Section Two

A Stark White Room

I felt safe . . .

And I favored a small white room.

The only thing missing in its authenticity was the distinct musk of oxidized semen. The door to this room was left ajar. Inside was a bare twin mattress and a fine drawing of two men hung unadorned above. The space intimidated me more than captivated me. The room spoke more to my notions of work than pleasure. It was a cheap and fast mystique, precisely what it was meant to be. I found a nook outside of the room with a worn-in vibrating chair under dim rose lighting. It was a disturbing space for anonymous viewing/interaction with the interior of that stark white room. I found it inviting.

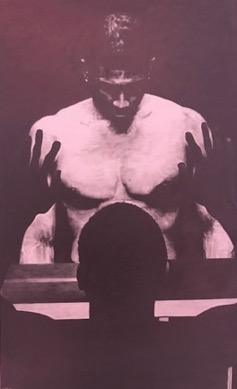

So, I approached not the room, but that small outside corner. It was slender and reserved for a single body. There was a waist-high hole cut into the wall that beckoned me into the private space and the lascivious acts I could imagine in between me and that wall. This consciousness reminded me of Bruce Nauman’s (b. 1941, United States) Body Pressure, where the viewer was invited to press their body against a wall as directed by the artist (fig. 2).5 Nauman first presented this one-page instructional text in 1974. He directed the viewer to concentrate on their body and its many parts contacting the wall and invited their senses into a potentially erotic experience. This silver-dollar-sized hole in Invisible Mxn gave me a bit of that fantasy. The more and more I pressed my body and knelt down to peer through the hole the more I made a choice to see through a glory hole.

What I saw were artworks in high-rendered detail pinned around the room (fig. 3). The one over the bed was about twenty feet from my vantage point but felt pressed into my space by the hole framing my perspective. The men in the drawing were in the grandeur of pleasure. The drawings were beyond the detail of a camera and on the level of decadence imposed by the great masters and their select protégés. Here, D’Angelo and Usher were in various states of composure (fig. 4).6 The smooth carbon of their detail hung in a curious but bold fashion inside that room. The works were tacked up, frameless, with punctured corners and clear push pins. One just floated above a stripped mattress with a bottle of hand sanitizer on the floor. There were sweepings of pencil dust, condom wrappers, and hair nearby. These captivated me most, the tender and filthy leavings of a fleeting intimate space.

Section Three

Étant Donnés and A Carcass

“Those sheets are dirty and so are you.”7

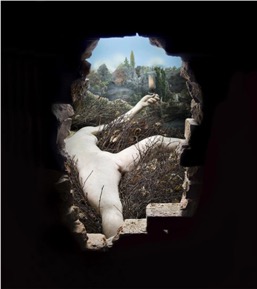

The drawings and their environment were a fetching simulacrum (fig. 5). The show offered up an underground sex space in an academic gallery but its content kept close to stigmatized reality. This enabled the viewer to handle the idea like a mirror and see themselves in it. Invisible Mxn then built up and offered an independent expression. That hole and the room to gaze upon relayed the shortcomings of a previous artistic voyeuristic exercise: Marcel Duchamp’s Étant Donnés (fig. 6).8 This final work by Duchamp (1887–1968, France) was made in secret from 1946 to 1966 and now exists as an unfinished posthumous installation at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.9 Duchamp’s work begins with the viewer as voyeur. A wooden barn door features two eye holes. Beyond that, in the guts of his installation a woman is laid bare in a pile of brush. She is both languid in her sexual moment and preserved in someone else’s sight. Her position is completely absent of blessing—you are not her lover. Here, the viewer looks on to the genitals first and body second. The face is not visible.

Duchamp shared his salacious sightline with an acute awareness of posed voyeurism. Peacock built on this in Invisible Mxn by requiring viewers to move through their thoughts and become implicated in this imagined but real space. Invisible Mxn asked one to bask in more than the funk and rigor of modernity and decide this was indeed a better hole. This fresh work smacks of risk. The blurred lines of implied consent take the viewer into their own knowledge and engagement. This risk is in fact an act of care. It was a measure of understanding and choosing intimacy over respectability.10

I digested my thoughts, I let myself imagine Usher and D’Angelo as two anonymous men fucking for money. This work left enough space for me to project sex work. It was playful but severe. To me, these figures were just getting down in a safe space following a hard day of jacking off johns for occasional good tips. I saw myself playing pretend and felt the resistance to a canon of fine art dominated by white men. I do not care about their art, those canonized men who pay sex workers but perpetuate our criminality. Art and theory often require me to detach from life experience. This is an exclusionary tactic of cultural oppressions. More often than not, when folks of color and sex workers work their way into the verified spaces of institutional thought it is exploited. Ideas are put in the stead of lived experience and a distanced supremacy of abstraction takes precedent over the bodily and lived knowledge. More often than not this is perpetrated by someone who has more relationship to the john than the sex worker: it is the oppressor hushing the oppressed.11

That stark white room gave me space for honesty. For once, I did not feel separated. I knew little and cared less about the rules in art and life. I cared less and less about the purposeful exclusionary tactics in fine art. This kind nihilism galvanized and bettered my experience in this academic gallery. It weaponized that exclusion, turned it double agent, and made something obscure so tender and clear. Thank you.

Section Four

Echoes and Ripples

I was taken out and washed off. It made sense to go see the pool next. Yes, the pool—in a gallery, staged with great care (fig. 7). It was in a room made of four roughly fabricated walls framed with wooden scaffolding. There were manholes cut to climb through and peek up to a second floor. I chose to climb up first and look around. I felt disembodied, like a magician had severed me in half. I stood waist high and viewed rudimentary childlike caricatures and an odd collection of action figures. The school-daze doodles were contrasted by more rendered drawings. The drawings in this light revealed a wash of carbon so rich that they shined and dipped into dark monochrome like a lithograph. Neither the renderings or caricatures were treated as better than the other, all were hung with tacks and tape.

The pool featured a drawing set on top of a cheap plastic watermelon inner tube (fig. 8). The drawing lived on a thin membrane; in it, an adolescent reached toward the picture plane, foreshortened on a black-and-white checkered kitchen floor. His underage body was well drawn and presumably created over many tedious hours. All that labor atop a pool of water.

This repositioned the art. It endangered what is so often cherished. A well-made thing was left to float and, hopefully, not sink. I thought about our security, about what an unsafe place the art world is: the inhospitality of our schools with their slick prison pipelines, ideas of jobs framed out by insurmountable and regenerating social barriers, and most of all the staunch collections of museums reflecting the bias and trends. In these spaces, you cannot help but be co-opted if you want to stay afloat. And on that thin membrane of plastic, it was clear how much complexity there was in this danger. This pool was ominously tranquil. It was a powerful force turnt out into a trope. The devices Peacock used held the reaching boy from the playful and destructive liquid below.

Peacock positioned his work as both viewer and destroyer. The danger is not the water; it is that he brought the water into the formal space. Then put drawings that he labored on for weeks on top of that water and pinned others up with tacks and tape. Like a teenager in the bedroom of his parents’ house, it was self-aware and existed on this destructive membrane. It was an unsafe space where discussion about disease and criminality are part of a queer archive but never the sustainable lifeline in art.12 It is just the daily math where you and I are added to life in a deficit and then expected to thrive. Galleries are spaces of mistrust; they are white in appearance and rule. They are the ruthless modernist dregs of Duchamp’s money shot here to fetishize your labor and turn your art into something of which you can never be a part.13

All you can do is get tough.14

I still had my towel in my hand.

Section Five

Lunch

“I do not know if we can teach someone like this?”

This was a quote from one of Malcolm’s educators. It came up in a discussion over lunch between Malcolm, Alexa Smithwrick of Recess Gallery, and me. That day Malcolm had finished his thesis installation and we sat down to eat a meal and be present and supportive as Malcolm processed the idea of a complete but lonesome MFA. He said to Alexa and me, “Do you know what so-and-so said to me when I started here? They said, ‘I do not know if we can teach someone like this?’”15 Malcolm had attended that school to work with that artist. I have been teaching for ten years and a student and an artist for far longer so I know the double sting of that statement, what it is like to be told you are beyond help and without community.

Yet, I also know the perspective of a teacher feeling work that moves as fast as cutting wind, unstoppable and irreverent. That force is cataclysmic in a classroom. None of the other students know how to keep up and you hardly do yourself. It is not that you cannot teach that, train that, domesticate that—but why would you want to? To change the direction of an incredible nature? To shift or wield that? I like to stand back and watch it go, let it live. It is important to understand what bell hooks stated in “Against Mediocrity,” that the separation between what one already knows and what one ought to know puts folks in camps and creates conflicts.16 Knowledge and its impact can be weapons but if intuitive and lived experience is already doing that work, why interrupt?

Invisible Mxn filled that gallery. It brought me to the precipice of human pleasure and pain. I wanted to both be in it and run from it. It shared with me a climax of human experience that with the smallest misstep will retreat into the confines of one’s self and never offer its reprieve. I do not get pleasure often. I get to work. This space was a pleasure. It was the visual messiness and clarity of climax. It is something one struggles so hard to get to and tries so desperately to hold once you’re there.

So, maybe so-and-so was right. Do not try to teach that or put that in a camp.17 You cannot guide someone into their own joy or what defines that, no matter how good you are. Do, however, be a support and a resource. Make yourself warm to those who refuse to be told they are not allowed to live as themselves.18 After all, the mere pressure of not belonging is enough to make one fracture and fray.19 No, you do not teach it, you nurture the almost painful process of simply trying to be authentic.20 You create safety and support where none existed because we are all destined to fail and it hurts. If your presence in a life can offset odds of opposition then risk is the only option. Risk your comfort by not teaching but modeling radical kindness.

Interlude

Alexa’s Joy

“What is your race? Brooooonze!”21

Alexa’s ignition of laughter. An uproarious molten gold of happiness. It flowed through the air and seethed. There is power in this laughter. Alexa’s joy was a cardinal direction pointing to pure volcanic black rock and the edges outlined her wealth in the face of hate.22 I sat while she and Malcolm and another sweet friend named Brendan talked and sang to Destiny’s Child. I sat comfortably in my discomfort, at ease in their happiness. It is a pleasure to be around happy people. And that cadence of singing and laughter filled the fabricated and exposed walls of Malcolm’s exhibition.

We sat after hours in the gallery and drank that night (fig. 9). The work surrounding did not jump nor excite for anyone else. It fully allowed us to embrace it and for us to crumble and be rebuilt. We were in the power of what a person can do with their own two hands and we were in that together. That is where I witnessed Alexa’s joy. The giggles that undermine white supremacy.

See, there is casual violence in every day. In passive aggressions and invisible labors. It is the murder of black folks by cops and the hasty amnesia of the white world.23 Because until everyone had a camera on their phones not one media outlet cared about folks getting killed by the cops. The videos of Freddie Grey, Philando Castile, Sandra Bland, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Alton Sterling, and so many more changed things for a moment.24 Yet, every time a video would surface the media and its willing audience would abide by the hysteria for a few weeks and then patiently wait for another black or brown body to be maliciously killed and recorded. It was gross. Watch it on the news, act like you care for two weeks then move on. The vapid pseudo-consciousness should be met with a mass and fearless inventory of our cultural value system. Where are those videos today? Why aren’t they on the news? Like the decades before, black boys and men are still being killed by the cops.

Section Six

Dreams

I sat in the pool at Invisible Mxn. I was in my bikini with my roller-derby muscles and bruises and Alexa in her racy one-piece composed of tenuous strips of spandex. I kept thinking about the reach of our bodies. I kept thinking about these bodies, how they become the signs for privilege or oppression, most often not by choice. In this exhibition so full of choice and consent, taboo and risk, I thought about how we become ourselves under these circumstances.

I played with that sticky hate I have for how mean whiteness is. I chewed on it and on my disdain for respectability, pulling it in between my teeth and cheeks, wondering what it is made of, like old gum. Did you hear that cum is mostly sugar and fat? I heard it too. It was the only thing not in the exhibition, but it was everywhere. It was in the tender and sweet references to coming of age and learning to be. It was everywhere in between protected sex, raw sex, voyeurism, jail, sex work, consent, and so on. It was the intimacy of peeking through a hole and handmade adornments.

That force of life, spunk, cum, semen, jizz, all of it. From the drawings tacked and taped to the wall to the slick and dangerous surface that art lives on, to the little bits of curly dark hair sweeping across the floor. It was everywhere and for the first time I swallowed it all up and left with my belly full.

Conclusion

Invisible Mxn recreated a way of thinking about one’s place in the world as full of pain and eros among risk and pleasure. I was troubled, I bore visible scars. The exhibition saw this in me and others. It was presented in the darkened back room was dark where there was a mattress with a well-laid sheet and a full-size figure embroidered on it (fig. 10). The person was laid down, sick, and was pulling his ass to one side with his head tucked down. It was not a place of pleasure. But as I moved through the space it became a place of healing. There were pillows scattered about and in each satin pillowcase there was a recording. I sat and listened to a man—a family member of the artist—reflect on life and jail. I saw a stack of books in the dark and read some pages from No Tea, No Shade.25 I did not feel better but I was alive and present in this vulnerable low note.

Candor like this does not play with the exclusivity of institutions. A life of fortitude with the ideals of class, gender, and queer exclusivity. It cannot vie for attention amongst the fronts of inclusive feminism foregrounded white supremacy. It does not pander to exclusion of sex workers and trans persons by Gloria Steinem.26 And it most certainly belies cultivation by the systems of white men.

There are notable dangers upheld by the pervasiveness of white women in the arts and activism. Those perpetuating the legerdemain of good intentions and no accountability are backed by racist ideology. This is the monster of people hiding in microaggressive shadows. They will come at you from those dark spots. I like to take note of this when I am comfortably tucked into my bed at night. I try not to forget that I may have cleared out my closet but I may have left something scary under my bed. Ideology rooted in ignorance may consume someone in their lifetime despite all good intentions. Just ask your neighbor in her pussy hat, how did she act when she got on the crowded DC train after the Women’s March and she had to share her space again? If you will not even slightly compromise your own advantage to help someone else you are truly invested in life?

____________________

Kristina Bivona

Kristina Bivona is a first-generation college graduate. She is currently enrolled as a doctoral student at Columbia University and holds a MFA and BFA in Printmaking. She uses critique formats informed by lived experience to enlighten the bridge between art practice and scholarship.

____________________

Footnotes

1. Smothering references a BDSM activity that reinforces the dominant/submissive relationship.

2. See Ralph Ellison, Invisible Mxn (New York: Vintage Books, 1989).

3. Malcolm Peacock, Invitation to Invisible Mxn (Rutgers University, 2019).

4. A man who purchases sex or sex acts is referred to in slang terminology as a john.

5. Bruce Nauman, Body Pressure, 1974, performance, variable dimensions.

6. D’Angelo and Usher are both musicians and performers. D’Angelo’s song “Untitled (How Does it Feel)” (2000) and Usher’s song “Confessions Part II” (2004) were both referenced in Peacock’s artworks.

7. Descendants, “Clean Sheets,” recorded 1987, track 1 on All: New Descendants LP, SST Records, 1987, vinyl LP.

8. Michael R. Taylor and Andrew P. Lins, Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2005).

9. During the twenty-year-plus timeline for the creation of this work of art, most assumed Duchamp had left his art practice solely to play professional chess.

10. See Alison Reed, “The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead: Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory,” in No Tea, No Shade: New Writings in Black Queer Studies, ed. E. Patrick Johnson (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).

11. By either holding a relationship to the oppressor over the oppressed, or by being the oppressor.

12. See Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality (New York: Pantheon, 1978) for more on this idea of disease and criminality; Melody Pennell, “Queer Cultural Capital: Implication for Education,” Race Ethnicity and Education 19 no. 2 (2015): 324–338.

13. See Mark Wigley, White Walls, Designer Dresses: The Fashion of Modern Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995).

14. Audre Lorde, “The Uses of The Erotic,” in Sister Outsider (Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 1984), 87–91.

15. Malcom Peacock, in conversation. February 15, 2019.

16. bell hooks, “Against Mediocrity,” in Writing Beyond Race: Living Theory and Practice (New York: Routledge, 2013), 165–166.

17. bell hooks, “On Being Black at Yale: Education as the Practice of Freedom,” in Talking Back: Thinking Feminist- Thinking Black (Boston, MA: South End Press, 1989), 63.

18. See Lauren Berlant, “Cruel Optimism,” in Cruel Optimism (London: Duke University Press, 2012).

19. Ibid., 6.

20. hooks, “On Being Black at Yale,” 63.

21. Malcolm Peacock, quote from Instagram Live video, February 20, 2019.

22. Audre Lorde, “Power” in The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde (New York: W.W. Norton & Company), 215.

23. Joni Boyd Acuff, “Failure to Operationalize: Investing in Critical Multicultural Art Education,” Journal of Social Theory in Art Education 35 (2015): 30–43.

24. Jasmine C. Lee and Haeyoun Park, “15 Black Lives Ended in Confrontations with Police: 3 Officers Convicted,” The New York Times, May 17, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/05/17/us/black-deaths-police.html; this article documented men and women assassinated by the police in the early 2010s.

25. See E. Patrick Johnson, ed., No Tea, No Shade: New Writings in Black Queer Studies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).

26. Rachel Cargle, “Unpacking White Feminism” (lecture, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, March 20, 2019).