‘Keep Hands Off Them’: The Case of the Priapic Votives at the British Museum

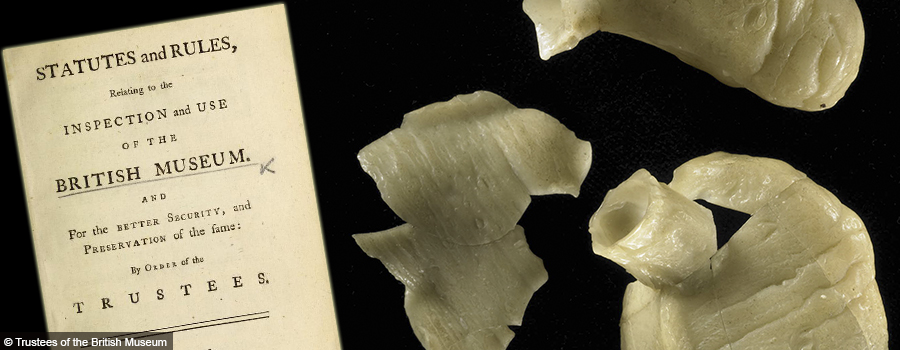

In 1784, the antiquarian Sir William Hamilton donated a group of phallic-shaped votive sculptures to the British Museum. These votives were used in cult rituals to the ancient fertility god Priapus, which Hamilton had researched in Southern Italy on behalf of the Society of Dilettanti. There were five votives in total, each hollow and modeled in wax. Hamilton’s bequest was accompanied by a note to the museum’s Keeper of Natural and Artificial Productions: “keep hands off them.”[1] The note was tongue-in-cheek, but apparently he had reason to be concerned. Today the votives lie in pieces in storage, broken at an unspecified time in the museum’s history (fig. 1).

This essay follows the case of the broken votives. After the bequest letter of 1784, the votives disappeared from museum records until 1865. In 1865, when the votives were inventoried for the first time, it was noted that two of the five were broken. In 1995, over a century later, when they were inventoried for a second time, all five were found broken.[2] With the scarcity of documentation from the period, it remains a mystery how and when the votives were shattered.[3] In current British Museum records, the damage is noted as a result of their “unusual fragil[ity].”[4] Surely the fact that the votives are hollow made them easily breakable, but since wax does not decay the only explanation is mishandling of some kind. While these phallic objects and their “castration” have inevitably prompted Freudian analysis by other scholars[5] (indeed Freud himself was aware of them),[6] this essay focuses instead on the conditions of their custodianship to understand how they might have broken, uncovering banal but equally revealing “slips.”

When the votives were acquired, the British Museum had been in operation for twenty-five years and was the first-ever public museum. The neglect of the votives can be attributed to their marginalization as erotic curiosities, and indeed, censorship played an important role in their history, especially during the nineteenth century. But the case also shines a light on wider incongruities between cultural custodianship in Enlightenment theory and in practice.[7] Most notable is the fact that at the time the vases were donated conservation did not yet exist as a professional field, revealing a fundamental attitude toward the care of museum objects.[8] Specialists in restoration were hired by the British Museum only in the mid-nineteenth century, and there are no surviving accounts of prior conservation efforts.[9]

The physical treatment of the votives was also a function of administration. In spite of their exalted provenance—Hamilton was a trustee, as well as the benefactor of the museum’s most prized collection of Greek vases—the votives were never officially registered in museum catalogues or inventory lists when they were received. Hamilton’s bequest letter of 1784 is the only record of the votives’ presence in the museum for over eighty years.[10] Such bureaucratic inattention was common in the nascent museum through the early nineteenth century, despite the Enlightenment’s apparent enthusiasm for classification: objects on display were not labeled, and there were no codified registration practices.[11] The inventories of the department of Natural and Artificial Productions, to which the votives belonged, were particularly disorderly—a result of departmental priorities, especially under the directorship of Joseph Banks in the 1780s, who snubbed ethnography and “artificial curiosities” in favor of natural history.[12]

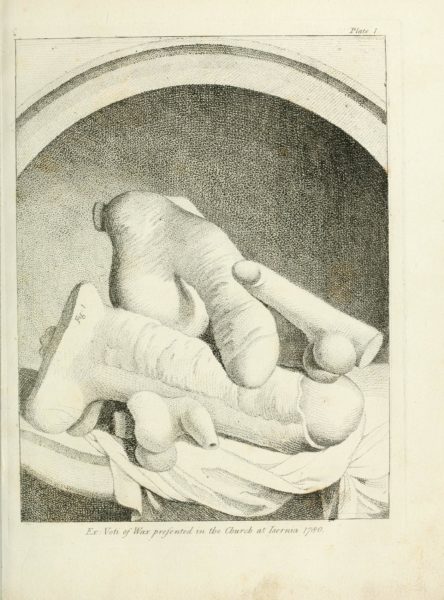

In the case of the votives, however, passive administrative blind spots are hard to discern from active institutional censorship. In 1786, soon after donating the votives, Hamilton’s research on priapic cults, along with fellow antiquarian Sir Richard Payne Knight, was published in an extensive volume. The volume’s frontispiece is illustrated with engravings of four of the votives (all intact), alongside a preface by Hamilton stating his intention to “deposit [these] authentic proofs…in the British Museum, when a proper opportunity shall offer” (fig. 2).[13] Almost a decade later, in the mid-1790s, a wave of conservatism from within and outside the antiquarian community launched a campaign against the publication, deeming it obscene. But while the text was a continual source of outrage through the early nineteenth century,[14] the votives remained unaccounted for in the museum (at least in extant records).[15]

Because of the lack of the records, it is unknown whether the votives were publicly exhibited (at least before the backlash against the priapic study) or where they were stored. Hamilton’s significant correspondence with museum officers leading up to the bequest suggests that he expected for them to be seen, and his collection of other antique phallic objects was already on display.[16] Whatever the case, as the property of all British citizens, objects inside the fledgling institution were inherently exposed to mishandling. Indeed, the ideal of public access—though often debated by officers in chauvinistic class terms—posed legitimate and practical challenges to the safety of the collection (fig. 3).[17] Objects were locked inside exhibition cabinets under glass or wire, though touching was sometimes allowed by the Keeper or Assistant to the department who held the key. Reading and study rooms, where objects were available for close examination by appointment, provided further opportunities for contact (and thus damage). According to museum policy, the Department of Artificial and Natural Productions was open for study “in a more private way” after normal museum hours.[18]

In his correspondence with the museum, Hamilton expressed concern about how the fragile votives would fare in transport.[19] But the bustle inside Montagu House presented a risk, too, as the museum grew. “Nothing is in order, everything is out of place,” complained one visitor to the collections, “and this assemblage appears rather an immense magazine, in which things have been thrown at random.”[20] Hurried tours and understaffing were also a burden, as were departmental overhauls.[21] Meanwhile, the collection was entirely moved to accommodate the 1823 demolition of Montagu House, which had become increasingly run-down, as well as for subsequent expansions of the new building (fig. 4).[22]

When the objects finally appeared in the museum records, it was not out of a fulfillment of an Enlightenment impulse, but rather a Victorian one. In 1865, the votives were listed, with two noted as broken, in an inventory of newly acquired antique phallic objects donated by collector George Witt, including two wax votives identical to Hamilton’s.[23] The Witt Collection prompted the establishment of what came to be known as the “Museum Secretum,” a special repository for obscene objects located in the basement of the museum, available for public viewing only with written permission.[24] It is not clear how long the votives had been inside, however; before Witt’s donation, a similar cabinet had existed informally since the 1830s.[25] It is a revealing insight into the administrative suppression of the votives and may also have contributed to their damage—objects inside were haphazardly stacked on top of one another and not labeled or organized by type.[26]

In 1995, in preparation for Vases and Volcanoes, the British Museum’s exhibition on Hamilton’s collecting practices, the votives were brought out of storage once again and inventoried.[27] In the age of modern conservation, the case of the votives continues to unfold. When it was discovered that all five were broken, conservators reconstructed two of the votives to be displayed in the exhibition (fig. 5). Hamilton’s dirty joke, “keep hands off them,” has proven prescient. From whole to broken to restored, the votives are a testament to the inevitably human hands of museum administrators over two hundred years.

Roxanne Smith

[1] Quoted in Ian Jenkins and Kim Sloan, Vases and Volcanoes: Sir William Hamilton and His Collection (London: British Museum Press, 1996), 238-239.

[2] In the register from 1865, it is noted that two (now catalogued as M.562 and M.563) were broken. See Jenkins and Sloan, 238-39. See also Giancarlo Carabelli, In the Image of Priapus (London: Duckworth, 1996), 131.

[3] Ian Jenkins, Curator at the British Museum, e-mail message to author, March 8, 2017; the book In the Image of Priapus by Giancarlo Carabelli provides the most thorough accounting of the primary sources relating to the votives in museum archives, to which this article is indebted.

[4] “Collection online: anatomical votive,” The British Museum, accessed March 5, 2017, http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=41139&partId=1.

[5] The cultural psyche framing Hamilton’s priapic study and its reception is described in depth by Giancarlo Carabelli in The Image of Priapus, as well as in work by Whitney Davis. See Whitney Davis, “Wax Tokens Of Libido: William Hamilton, Richard Payne Knight, and the Phalli of Isernia,” in Ephemeral Bodies: Wax Sculpture and the Human Figure, ed. Roberta Panzanelli (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2008), 107-129; see also Whitney Davis, Queer Beauty: Sexuality and Aesthetics from Winckelmann to Freud and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010): 51-81.

[6] Freud was aware of the votives through Hamilton and Knight’s 1786 publication on priapic rituals. See Davis, “Wax Tokens Of Libido,” 109.

[7] For discussion of the Enlightenment intellectual climate in which the British Museum originated, see Robert G.W. Anderson, “British Museum, London, Institutionalizing Enlightenment,” in The First Modern Museums of Art: The Birth of an Institution in 18th- and Early-19th-Century Europe, ed. Carole Paul (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2012), 47-72.

[8] Sarah Staniforth, Historical Perspectives on Preventative Conservation (Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, 2013), xv.

[9] “Conservation and Science, History of the Department,” The British Museum, accessed March 5, 2017, https://www.britishmuseum.org/about_us/departments/conservation_and_science/history.aspx.

[10] Carabelli, 131.

[11] The issue of mismanaged inventory lists continued for decades and was so endemic that in 1836 a Parliamentary inquiry required the project of registration to be completed. See David Mackenzie Wilson, The British Museum, A History (London: British Museum Press, 2002), 87.

[12] Ibid., 40.

[13] Richard Payne Knight and Sir William Hamilton, An Account of the Remains of the Worship of Priapus,lately existing at Isernia, in the kingdom of Naples (London: Printed by T. Spilsbury, 1786), 4.

[14] Edward Hawkins, who served as Keeper of the Department of Antiquities from 1826 to 1860, was particularly forthcoming in his censure of the text in 1808, referring to it as a “disgusting production.” See Catherine Johns, Sex or Symbol? Erotic Images of Greece and Rome (New York: Routledge, 1982), 26.

[15] Carabelli, 113.

[16] Hamilton requested that they be displayed alongside his other collection of phallic objects from Herculaneum, already on display in the museum. Letter from W. Hamilton to J. Banks, 17 July 1981: London, British Library, Add. 34048, ff.12-14; for further description of this correspondence, see Carabelli, 1-3.

[17] Wilson, 36.

[18] Ibid., 37.

[19] Hamilton wrote to Joseph Banks in 1782, “I have waited in vain for a good opportunity of sending Solander the collection of Ex voti… They are too valuable to [be] risked at Sea during the war & too fragile to be sent by land.” See Letter from Hamilton to J. Banks 23 April 1782: London, British Library, Add. Ms. 34034, f. 16.

[20] Quoted in Wilson, 40.

[21] Description of the logistical issues facing the museum at this time may be found in Ibid., 35-42.

[22] Anderson, 67.

[23] Carabelli, 131.

[24] Wilson, 166.

[25] Johns, 29-30.

[26] Carabelli, 1.

[27] “Collection online: anatomical votive,” The British Museum, accessed March 5, 2017, http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=41139&partId=1.