Architecture as Evidence/La preuve par l’Architecture

![Installation view of Architecture as Evidence, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal, 2016. © CCA, Montréal [Featured image]](/sequitur/files/2016/11/milosz_2016_06_16_MB_027-e1480441385254.jpg)

Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal

June 16, 2016 – September 11, 2016

A letter to a contractor stresses the urgency of a previously placed order for a hatch to be added to a roof. On an architectural plan, the hinges of a door have been reversed. Photographs show crowds of people, or an aerial view of a building. These fragments add up to an archive that attempts to answer a question: without the witness, how do we determine truth? Architecture as Evidence / La preuve par l’Architecture, a recent exhibition at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), was based on archival material collected to demonstrate the historical reality of engineered death at Auschwitz. A 2000 legal trial in which this material was entered as evidence was an opportunity to answer the question above. No survivor-witnesses were called to the stand. Instead, the evidence had to speak for itself, just as it did in this exhibition.[1]

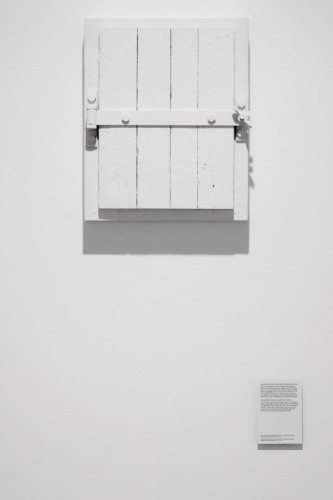

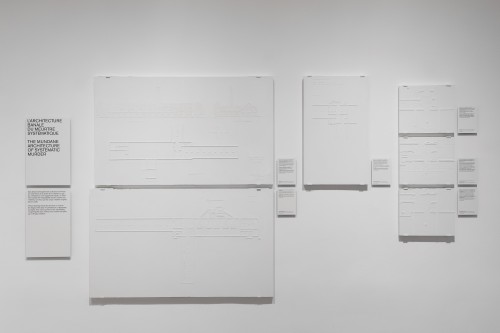

The exhibition curators translated that evidence—letters, plans, and photographs normally preserved as unalterable elements of the historical record—into white plaster casts that both obscured and substantiated their subject matter. Created from laser-cut basswood and acrylic molds that added depth to the two dimensions of the archival records, the casts were hung around the perimeter of the CCA’s Octagonal Gallery. Together they provided documentary context for two additional reconstructions also rendered in white: a gas column and a gas-tight hatch—the bare architectural implements used to kill up to 2,000 camp prisoners a day. The language used by the curators to describe both the artifacts on display and the murderous processes of the Nazis—systematic, basic, mundane—conveys Hannah Arendt’s notion of a “word-and-thought-defying banality of evil.”[2]

Architecture as Evidence was a smaller version of an installation called The Evidence Room at this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale (May 28 – November 27, 2016). In Venice the same curatorial team put together a similar series of objects, but also designed the room in which the evidence was displayed, evoking the spaces of gas chambers and courtrooms.[3] While using these casts literally threw the evidence into relief, the choice to render them in white made them difficult to read against the white walls of the gallery. That, however, was entirely the point. The usual high contrast of black-and-white photographs or typewritten text was lost to the monolithic white material, inviting careful scrutiny in place of preconceived understanding. The casts subverted the weightlessness of their originals and enhanced their own significance through their physical sense of gravity.

The Evidence Room in Venice contained one reconstruction that Architecture as Evidence did not: a door with a large peephole covered in a half-sphere of wire mesh, to prevent it from being smashed by those being murdered within the gas chambers. This omission, made perhaps for reasons of spatial or fiscal economy, was an unfortunate gap in the exhibition in Montreal. A door is a familiar, human-scaled architectural element that immediately connects with our embodied sense of movement, restriction and choice. The features of that door—the latch, wire mesh, and lack of a door handle on one side—are subtle perversions of our notion of a door as a portal to be moved through in both directions. Its inclusion would have emphasized the ways in which architecture can be appropriated to control and, ultimately, to kill.

Architecture as Evidence reminded visitors that history, as opposed to memory, allows no true forgetting, and the notion that society is able to learn from the “mistakes” of the past does not hold up. In a time when truth is so easily recast, the exhibition argued that architecture indeed plays a role in documenting and bearing witness to historical truth. What we do with that evidence is up to us.

Magdalena Miłosz

Further reading: http://www.theevidenceroom.com/

[1] Robert Jan van Pelt, “The Evidence in the Room and the Memory of the Offence,” in The Evidence Room, 81. Van Pelt published the archival research from the trial as The Case for Auschwitz: Evidence from the Irving Trial (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002). The trial is also the subject of a feature film, Denial (2016).

[2] Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (New York: The Viking Press, 1963), 252.

[3] Anne Bordeleau, “The Casts Court,” in The Evidence Room, 113.