“So-Called Synonyms:” Translating Darío de Regoyos’s ‘España negra’

I first became familiar with the paintings of Spanish artist Darío de Regoyos (1857-1913) at a survey exhibition held at the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, in Madrid, on the centenary of his death. Captivated by the sun-dappled fields and villages of Regoyos’s Spanish landscapes, I also began reading his 1899 travelogue, España negra. Immersing myself in the words of an artist whose brushwork I was simultaneously getting to know led me to translate the text, as yet unavailable to English readers. As I would soon discover, both translation and art history are fundamentally acts of interface—the former, the transposition of writing in one language into another language, and the latter, the evocation of objects with words.

In “Art History and Translation,” Iain Boyd Whyte and Claudia Heide ask, “What actually happens when a text crosses a linguistic border and what can art history learn from this process?” [1] Writer and translator Lydia Davis’s “Thoughts of Translation and Fiction” provides one insight:

As we translate it is not our own choice that confronts us, but the choice of another writer, and we must search more consciously for the right words…. It is then that we summon all the so-called synonyms in our own language, in the hope of finding just the right one. [2]

As Davis observes, there are only “so-called” synonyms between languages, and more obviously, between objects and words. Even so, approaching objects as translators reorients us, productively I think. With all the “so-called” synonyms at our disposal, we strive to attend meticulously enough to an artist’s choices to approximate their style and sense. In effect, we are asking the painting (or the paragraph), What are you trying to tell me?

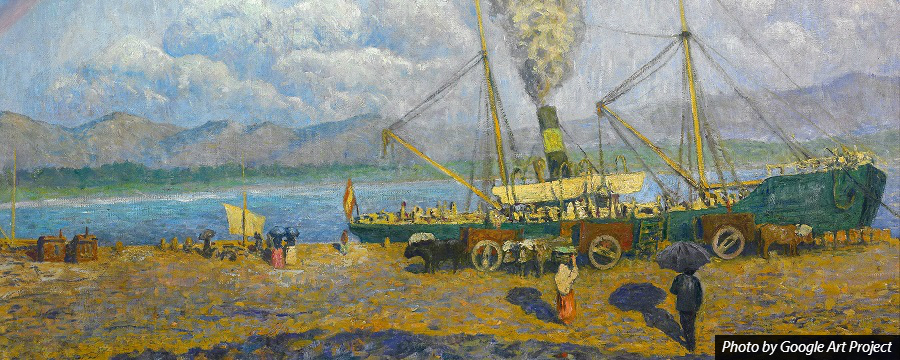

My translation of España negra from Spanish into English is the translation of an earlier translation from French to Spanish by Regoyos himself. In 1888, just over a decade before España negra was published in Barcelona, Regoyos and Belgian poet Émile Verhaeren, friends through the Brussels artists’s circle L’Essor, traveled together across northern Spain. As Regoyos painted, Verhaeren composed four articles describing their journey, all featured between June and August of 1888 in the Belgian French-language review, L’Arte Moderne. [3] Near the century’s end Regoyos translated his friend’s articles, each headed “Impressions d’artiste,” from French into Spanish, and embedded over thirty reproductions of his prints and paintings in the text. [4] In the prologue to España negra, Regoyos characterizes his book as a “translation of [Verhaeren’s] travel impressions of Spain” and requests that he “not [be] taken for a writer, but for the companion of the Flemish poet.” [5] However, in his translation of the book, Regoyos shifts the narrative perspective from Verhaeren’s to his own, adds new descriptive passages, and significantly alters the overall structure of the text. Perhaps most noticeably, Regoyos also reorients the narrative around his conviction that Verhaeren, “far from viewing [Spain] in a happy manner like most foreigners who see blue skies and the apparent joy of bullfights, felt a Spain morally black.” [6] Regoyos, then, in addition to negotiating between languages, negotiates between subjectivities, mediums, formats, and cultures—not unlike practitioners of art history. In doing so he seeks out “so-called” synonyms, in the form of prints, paintings and words to express and also alter Verhaeren’s account, creating an “España Negra” of his own in the process.

Annemarie Iker

____________________

Endnotes:

[1] Iain Boyd Whyte and Claudia Heide, “Art History and Translation,” Diogenes 58 (2011): 49.

[2] See Lydia Davis, “Some Notes on Translation and on Madame Bovary,” The Paris Review 198 (Fall 2011): 65.

[3] Verhaeren published his four articles in L’Arte Moderne (of which he was also an editor) on June 17, July 8, July 22, and August 5 of 1888.

[4] For the original 1899 España negra see the edition published by Hesperus (José J. de Olañeta, editor) in 1989. Also worth reading is Mercedes Prado Vadillo’s facsimile of España negra (Bilbao: El Tilo, 2004), which contains a helpful publication history, and the exhibition catalogue Darío de Regoyos (1857-1913) (Madrid: Fundación Cultural Mapfre Vida, 2002), for a more general survey of the artist’s career.

[5] In the Spanish, Regoyos’s note “Al público” reads, “Que no me tomen por escritor, sino por compañero del poeta flamenco, es lo que más deseo y ruego al público antes de leer estas impresiones de viaje.” See España negra, edited by José J. de Olañeta (Palma de Mallorca: Hesperus, 1989), 27.

[6] “… lejos de verlo de una manera alegre como la mayor parte de los extranjeros que nos ven al través del cielo azul y de la alegría aparente de las corridas de toros, sintió una España moralmente negra.” Regoyos, España negra (Hesperus, 1989).